Hallway Space installation view, Mark Benson “Open Fields”, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Mark Benson, “Open Fields” detail view of Gerber Daisies, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Mark Benson’s installation in the Hallway Space at the entrance of Eli Ridgway Gallery is dying. When I arrived less than a week after the opening, the plants already looked sad, droopy and discolored. They epitomize the decay of excess and the possible futility of gifting living things. Purchased and presented in colorful gift-wrapped pots, the plants are hopeful emblems of social ceremonial left contingent upon the caring nature of the recipient. Some of the plants are perennials, the red Gerber daisy for example – which are not sustainable in pots because they die back every winter and then it will most likely be thrown away. But that does not keep people from growing them and packaging them for sale as gifts – they are one of the most popular commercial flowers. If the daisies were planted in the ground one could expect it to resurface the following spring, but here it will live a sundry, temporary life. Installed on shelves too high to admire head on, the pairs of plants are emblematic of the precarious nature of coupled relationships. Because they are hard to care for at this level, a profound notion of life and death occurs when viewing them with a craned neck looking upward. The high placement renders them inaccessible above the packed group show inside the gallery. Seeing this work first reiterates the notion of object subversion between the relationships of galleries to objects, be it from a conceptual curatorial perspective or objects as commodities.

“Summer Show” at Eli Ridgway Gallery is a sampling of artists from the gallery – somewhat of a mid-year survey of who they show. The artists included are: Lindsey White, Chris Duncan, Wolfgang Ganter, Matthew Palladino, TV Moore, castaneda/reiman, Cassandra C. Jones, Jeffrey Simmons, Travis Collinson, Sean McFarland, Brion Nuda Rosch, James Sterling Pitt, Rebecca Goldfarb Zachary Royer Scholz and Mauricio Ancalmo. Parceled amongst the spaces within the gallery are two additional solo exhibitions: “Open Fields” by Mark Benson and “Salt Water Battery” by Andrew McClintock. There is a lot to see here. The reasoning for the way the show is installed seemed to reiterate the commerce purpose of galleries. I was compelled to tie this commodity concept in with Benson’s work which is a remark on the purchase of an idea rather than a lasting object. The show is hung really well, but editing would have benefitted viewers to a “taste” rather than a survey, some artists represented by one piece and others represented by too many, making for a diluted experience in some cases. Nevertheless, if the purpose is to show an assortment of work visually leading from one to the next, it is successful at that. I walked the rooms and found connections that lead from line, to the subversion of objects, and the sublime resonance of nature – but ultimately a question of purpose and place was looming in my mind.

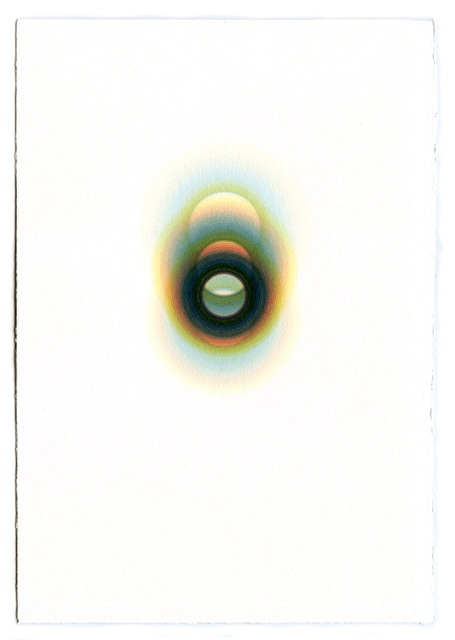

Jeffrey Simmons, “Resonator II”, watercolor on paper, 15″ x 10.5″, 2012. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Cassandra C. Jones, “Dog”, archival inkjet print, edition of 2, 44″ x 44″, 2012. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

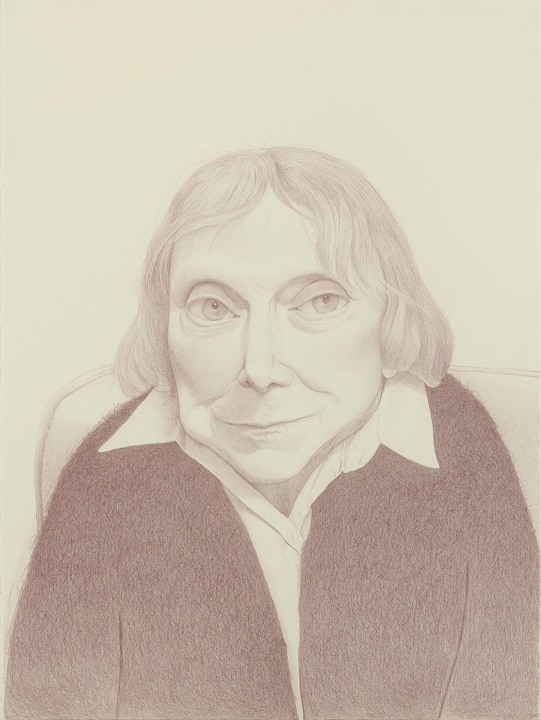

Travis Collinson, “Paule”, color pencil and graphite on paper, 30″ x 22″, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Jeffrey Simmons “Resonator” and “Chromatic Resonator” series are captivating, delicately repeated circles of intensely bright colors, surrounded by softer auras that give the shapes an astral dimension. Facing Simmons’ work is Cassandra C. Jones “Dog”, an assemblage of lightning images frenetically clustering the electricity that cracks lines through the sky during storms. Looking on, Travis Collinson’s fine pencil drawings are superbly rendered and eerie – the portrait of San Francisco gallery icon Paule Anglim strangely perverse and at once quite sweet. In contrast, James Sterling Pitt’s sculptures also lend themselves to drawing and line, but here the traces of the hand that made the lines render them as a three-dimensional form. The repeated thin strips and outlying softly curved rectangle edges of the sculpture show traces of the hand working the tools to cut the shapes. Segments are carefully painted in analogous, modern colors allowing the irregularities of the surface to show underneath. Acting as remnants of gesture and internal dialog, the pieces engage with a quiet and unpretentious conversation with the psyche. Nearby, an alluring and unsettling abstraction draws my attention.

James Sterling Pitt, “Untitled (undercurrent)”, acrylic on wood, 21.5″ x 18″ x 2.5″, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Zachary Royer Scholz, “2697212 (orange velvet), 69″ x 72″ x 2″, 2012. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

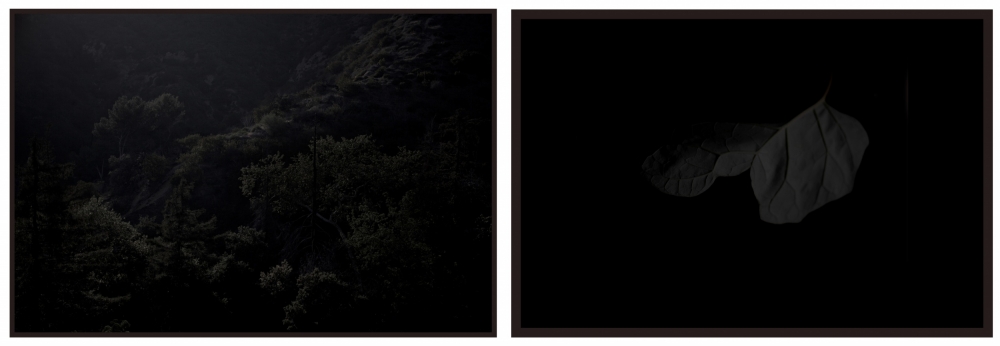

Sean McFarland, “Untitled (ridge)”, archival pigment print, *” x 12″ each, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

Zachary Royer Schulz’s “2697212 (orange velvet)” is a canvas stretched with the covering of a deconstructed couch or armchair. The velvet is permanently creased by the stitches that once made puffy columns punctuated with matching cloth covered buttons. The areas that withstood sitting in the original object’s past life have left a brownish stain across what now acts as a monochromatic painting. The piece occupies a space between the ready-made and painting, between Color Field and abstraction. More importantly, it has the traces of what we know it to be, yet that object is not before us. Across the way, “Untitled (ridge)” by Sean McFarland is also not what it seems.

Chris Duncan, “Skylight #2 (4 months)”, fabric and sunlight, 61.25″ x 57.25″, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

From a distance, the photographic diptych appears to be simple black monochromes, but upon closer inspection the haunting, barely visible trees and leaves on a rich black ground come into view. This work engages in a magnetic draw that reveals a subtlety of the sublime in a satisfying way. On view were also McFarland’s tiny black and white landscape images, including two “portraits” of the moon. McFarland’s nature studies are in compelling conversation with Chris Duncan’s sun-oriented work.

Duncan’s pieces in the show document and hold the power of the sun and the fragility of time and are a continuation of his long fascination and study of the sun as a generative life-force. The three large works entitled “Skylight” [“#1, (8 months)”; “#2, (4 months)”; “#3, (4 months)”] are large black and brown fabrics that were placed over skylights. Over time, the sun bleached away the color, leaving behind ghostly impressions, the brightest in the center where the glass of the skylight shone the light of the sun most directly, fading along the sides where it cast in at angles, and dimmest along the edges where the fabric was concealed from the sun’s radiation. While I was there, I and another visitor to the space asked if they were photographs – and in a sense they are – the result of a chemical reaction between the sun and the pigment-dyed fabric is very similar to the sun responding to photo-chemically treated papers or fabrics. The pieces are inconceivably wondrous – each crease, fold and wrinkle of the fabric glows with the permanent aftermath of the sun’s light. In contrast, Mauricio Ancalmo’s installation “War Footage [Fourth Articulation]” stood quietly in a dim corner.

A soft sound emanated from the sculpture. This piece has a stoic quality, in comparison to Ancalmo’s dynamic, kinetic work that I have seen over the years. Here, the projector is rendered as a blind object, purposefully not illuminating the traverses of war. Rather, the red bundle of leader tape alludes to the bloodshed and trauma of war. Virtually inaudible and showing no detail of human presence the piece makes a very poignant point about loss and brings to mind the ridiculous effort that war entails and the fragility of human life.

Andrew McClintock, “Salt Water Battery”, aluminum, copper plates, copper wire, soldering wire, electrical tape, nylon, water, salt, dimensions variable, 2013. image courtesy of Eli Ridgway Gallery

In the adjacent room Andrew McClintock’s “Salt Water Battery” installation reiterates similar futile efforts. In full disclosure, McClintock is the founder & publisher of SFAQ, but also an artist in his own rite, as is almost everyone affiliated with the publication, including myself. With that, objectively speaking, the painstaking accumulation of pounds of salt and the laborious effort to assemble containers with copper rods and wires to generate electricity are all the makings of glorious potential. Yet, the construction of all of this effort is only powering eight very tiny LED lights that barely illuminate the installation itself, let alone the room. There is humor in the irony of this piece, but the curiosity of purpose still bothers me more – the precise care and elaborate configuration of the objects coupled with futility of the tiny lights seemed to be telling the story of some ominous future. But perhaps there is a light at the end of the tunnel?

Ridgway shared with me some possible future ideas of opportunities for his artists and some thoughts on his position as a gallery next door to the huge reconstruction/temporary closure of the neighboring SFMOMA. Ridgway’s gallery is a destination now challenged by neighboring upheaval and transition. Lately I have been worried for the state of San Francisco’s state-of-the-field of contemporary art. Knowing that the city would be parceling out its curatorial endeavors around the city is an exciting solution to keep its presence known, but also a precarious one without a home-base intact. As I was leaving I looked again at Mark Benson’s “Open Fields” installation and pondered how intentional the foreshadowing seemed to put these fragile plants just out of reach and facing an uncertain future. But as with all great endings, there is the excitement of new beginnings and the hope for greater purpose.

For more information visit here.