On the “lower most” frontier of the LES galleries is Pocket Utopia, on Henry street, where you can unexpectedly face late 18th century visions of Arcadia tucked inside a scrappy storefront—a pocket utopia if there ever were. “The Thrill of the Ideal,” subtitled, “Richard Tuttle: The Reinhart Project,” is a collaboration between the uptown print dealer C.G. Boener, Pocket Utopia, and Richard Tuttle.

I believe Tuttle is our most intelligent living artist; his work is always pushing me to think harder, more sensitively, differently. I didn’t fully understand how dazzling his mind was until I started corresponding with him for a long alphabetic interview in The Brooklyn Rail several months ago, and I’m still reflecting on the complexity of his responses. In the course of our conversation on symbolic versus non-symbolic form, the proto-romantic artist Johann Christian Reinhart came up as someone he sees as creating solutions between the two modes in a single image. This of course made me all the more excited to spend time looking at a group of Reinhart prints Tuttle selected.

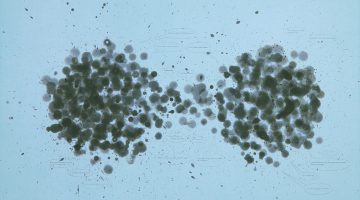

Because they are prints made for a portfolio they want you to be close, to hold them. The framing reinforces their physical presence: irregular and aged sheets floating against black mats in black frames. If I had one, I’d hang it on the wall against my bed, at pillow level, so I could really look at it in the morning light when the paper would be the most creamy bright against velvet black ink. They are all leafy landscapes witnessing nature overtake some form of crumbling ruin, with a strolling shepherd or artist somewhere in the scene. The vegetation is astonishingly carved out of light and darkness—your eyes move over individual leaves in a shimmering glissando up piano keys, discrete marks making surfaces melting into masses.

My favorite has a lone figure laying with arm over his face near the opening of two caverns, remnants of some collapsed building. To be sleeping in the sun, or dreaming, or thinking, near those yawning darknesses strikes a strange chord, permeating the idyllic setting with a sense of emotional or psychological vastness. The animals frolic mostly unaware, going on with their doggy lives as Auden once said, and so do the people—citadels crumble and become host to peasant picnics, while the sky moves overhead with its own concerns.

The image is a balance of subtle diagonals and the registration of the print on the page is itself tilted. The upper edge of the paper is cut at an opposing angle so it all rocks back and forth. It is serene and violent.

For more information visit here.

-Contributed by Jarrett Earnest