Hollis Frampton: By Any Other Name

Room East

41 Orchard St New York, NY 10002

October 30 — December 23, 2016

“The red filter is withdrawn. / Our white rectangle is not ‘nothing at all.’ In fact, it is, in the end, all we have.”

—Hollis Frampton, A Lecture, Hunter College, 1968

In retrospect, the “red filter” of Frampton’s lecture seems to be a direct reference to—or sly premonition of—Carrots and Peas (1969), the artist’s seminal film now on display in Room East’s exhibition Hollis Frampton: By Any Other Name, an abbreviated retrospective marking the iconic artist’s 80th birthday.

Installation view, Hollis Frampton: By Any Other Name (1979-1983), Room East, New York, October 30-December 23, 2016

Midway through this work, the vegetables (a polka-dotted array of basketball-orange and juniper-green forms, finding craggy kinship with extra-terrestrial terrain) flashes red: A vermillion veil.

This filter not only points to the medium’s qualities (a so-called single point objectivity, manufacturing the illusion of motion by streaming light through a series of negatives) but also the new reality forged by this ostensible unreality. The spread of serrated carrots and bulbous peas actuality does turn red. And the viewer, unable to opt out of this newly formed abstract narrative absorbs the unreality that Frampton shapes.

But what is the point of this narrative, non-narrative? And, how does it relate to the overall exhibition?

Hollis Frampton, still from Lemon, 1969.

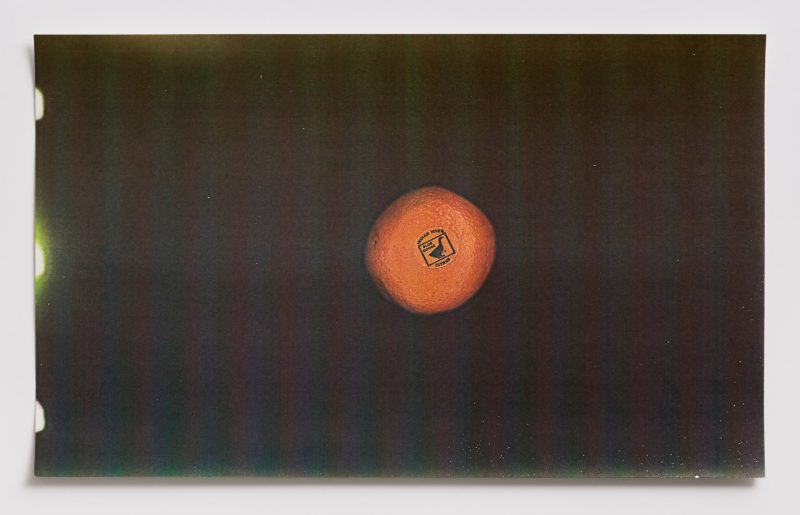

Carrots and Peas runs on a loop in the gallery’s split-level basement space, alternating between it and another Frampton film, Lemon (1969). Both works seem to be projected from a camel-colored two-reel film projector standing opposite the screen. (Although whether or not the footage actually comes from this device proves dubious, because the reels themselves appear not to be moving.) On the adjacent wall, bathed in a Vermeer-esque stream of light, hangs a Xeroxed picture of an orange (Blue Citrus Brand Goose, 1983) enclosed behind museum plexi. This facsimile—a glowing rusty bulb suspended in a sea of velvety black—reads more like a celestial body than a pulp-filled delicacy.

The projector clicks.

The film rolls over. Lemon begins. The pulsating fruit undergoes an eclipse—an oscillating waning, endowing the image with a kind of stellar potentiality. And, as the citrus orb slowly fades into black—never looping back to the expected ersatz sunrise—I realize what I just witnessed was probably a diminutive apocalypse.

Installation image, Hollis Frampton, Blue Citrus Brand Goose, 1983

The gurgling claptrap baritone underscoring Carrots and Peas suddenly becomes the narration of the moon landings or an opening monologue from The Twilight Zone, played backwards. The neighboring Xeroxed orange morphs into an iron-dusted planetary cadaver—hovering at a mocking distance.

Frampton’s use of Space Age aesthetics as a means to communicate farcical catastrophe comes as no surprise when one remembers the year in which both films were made—1969. This year—that of the actual moon landings—was the height of the Space Race (which can be thought of as one of many Cold War competitions simultaneously riddled, from an American perspective, with a sense of unprecedented Promise and the threat of nuclear extinction).

I wasn’t alive when the moon landings happened. I didn’t watch them (or their manufactured facsimile, that is) in real time, on television.

But, I can imagine the event. Not only the image of “Buzz” Aldrin stumbling out of Apollo 11 accompanied by Neil Armstrong grainily muttering,That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind, just seven days after the Soviet Union landed the first manmade object (Luna 2) on that selfsame surface, but also the eyes of every warm-blooded American, every nuclear family, glued to the TV screen—absorbing an identical set of images.

Hollis Frampton, still from Lemon, 1969.

Frampton’s films are special not only because they seem to point to new realities opened up by ostensible unrealities—a lexiconal formation and absorption of external events through image and sound itself (what critic Paul Adam Sitney clumsily dubbed the artist’s project of “structural cinema”)—but also how they refract and reflect these very fictions.

Frampton turns America’s Peas and Carrots into Carrots and Peas.

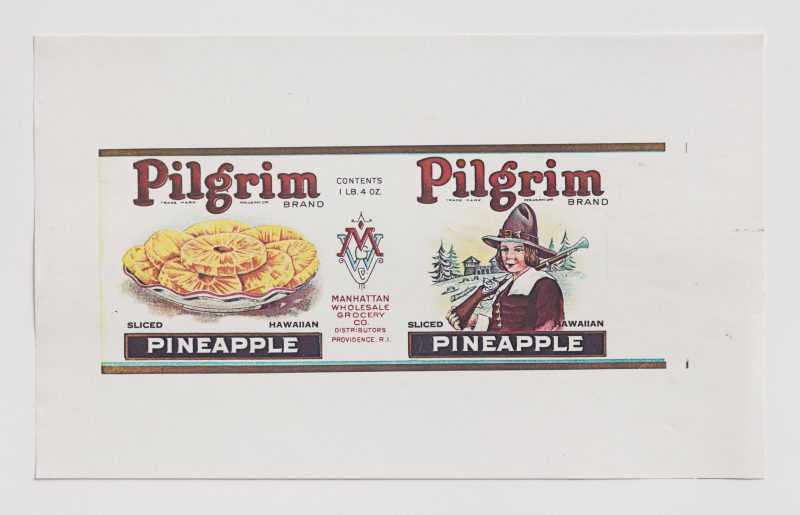

This dual project of deconstruction and reconstruction of American identity, through pointing to the underlying mechanism and operative capacity of image, continues upstairs where a series of Frampton’s Xeroxed vintage food labels from around the world (titled, By Any Other Name) hangs in panorama.

Hollis Frampton, Pineapple Brand Sliced Pilgrim, 1983. Color Xerograph, 8 1/2 x 14 inches

Although this work—unfolding in a stream simultaneously recalling a billboard, film reel, and chronology—was made 10 to 15 years after the featured films (1979-1983 as opposed to 1969), the labels themselves look even further back; many not only appear to be from the 1950s but most also display clear colonialist sentiment. Genuine Chutney Brand Indian Sun (1983), the only piece that gets its own wall—with its visual, farcical endorsement of the British Raj—serves as the launching point for the display: a touchstone from which the other labels (such as Clam Brand Whole Baby Geishas (1979), and Pineapple Brand Sliced Pilgrim (1983) flow.

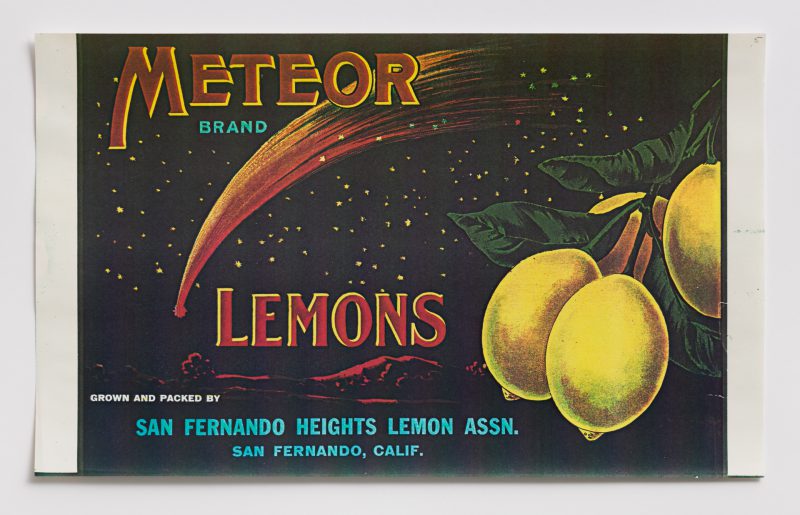

Hollis Frampton, Lemon Brand Meteors, 1983. Color Xerograph, 8 1/2 x 14 inches

The candy-colored food labels then become markers on an obtuse timeline, providing a quasi-genealogy of colonialism and capitalism, folding these histories in on themselves. And, although these inextricable—yet distinct—histories prove far more complex than the display might suggest, the piece clearly points to the operative capacity of image: its ability to convey and reify violence, as graceful silhouette.

But, that is not say that Frampton harbors only hatred or distrust for images. Instead, he seems to exhibit, actually, a kind of reverence for them.

The red filter is withdrawn. / Our white rectangle is not “nothing at all.” In fact, it is, in the end, all we have.

This statement serves kind of endorsement of image, I think. An optimistic mantra pointing to an image’s ability to not only perpetuate disaster—reifying peas and carrots as Peas and Carrots—but also, on occasion, transforming this duo into Carrots and Peas.