Ed Moses: Painting as Process

Albertz Benda

515 W 26th St, New York, NY 10001

September 8 – October 15, 2016

A point hovering just above absolute zero. A mark saying, I was here.

Ed Moses: Painting as Process—a modest retrospective of iconic West Coast artist Ed Moses, curated by the also iconic art historian Barbara Rose, presents a selection of Moses’s more elegiac works, excised from across his career.

The exhibition opens with Red W-L (1982)—a piece (which is part of the artist’s “Waterfall Series”)—which displays vast swaths of electric blood red splashes interrupted by jet black and opalescent splatters, bridging four distinct but descending varnished panels.

Ed Moses, Red W-L, 1982. Acrylic on wood panels, 84 x 122 in. Courtesy of Albertz Benda and The Artist

This viscous preamble of sorts then feeds into a room of gridded works. Moses started using the grid in the 1970s, first rotating the frame 45 degrees as a way of addressing its hegemonic orientation. And with this inverting and perverting of the schema in question—painterly drips become frosted veins running up an icy pane of glass, looking out on a barren Manhattan cityscape at 6 am, becoming wider, Midwestern cornfields from an aerial view of a San Francisco-bound airplane—these works could hardly be described as rigid. (See Moses’s Green Man, an acrylic painting on panel that took the artist from 1989 to 2004 to complete—the piece’s sea foam trickles weaving in and out of clouded rosy forms.)

Ed Moses, Green Man, 1989-2004. Acrylic on Canvas 66 x 54 inches. Courtesy of Albertz Benda and The Artist

Through the simple gesture of letting the formal structure (the reticulation) be subject to gravity (the medium slowly dribbling downwards with a realist physical and temporal bearing), Moses seems to be reckoning with questions of agency—of order and chaos, of control and submission.

But, submission to what?

Moses might say the inherent and esoteric tendencies of the medium—a humbling entropic drip. Or, perhaps he might hint at the intangibility of formal perfection, a mutability inherent to the form itself—the formal limits of the form. But, these drips do more than mediate false binaries. And, as the exhibition progresses to the next gallery, the conceptual overtones of these prior works begins to take on a fuller shape.

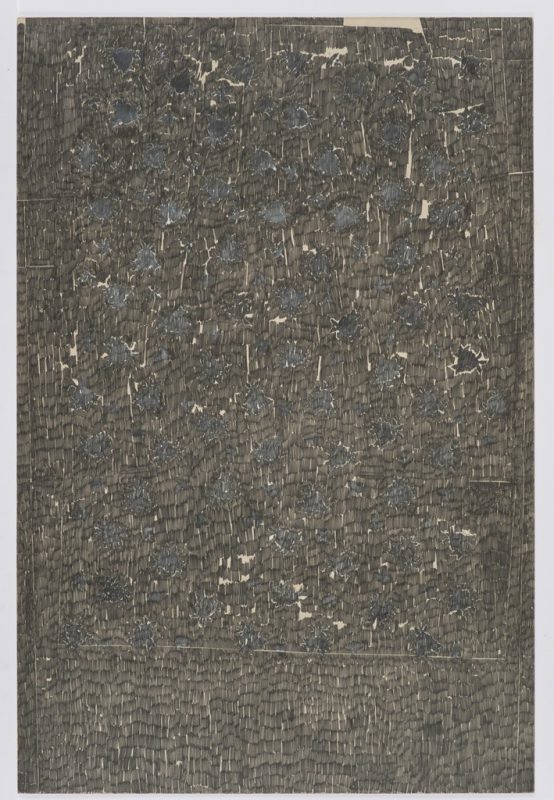

Here, the viewer finds Rose #6 (1963) and Wall Layuca #2 (1989), two contrastive pieces that both strike up a dialogue with nature imagery: a flower, a forest. And although this reading might be a tad reductive, I think it helps in understanding the conceptual space the work inhabits. Moses isn’t interested in imagery, per say, but instead (as the exhibition title “Painting as Process” legibly lays out) process.

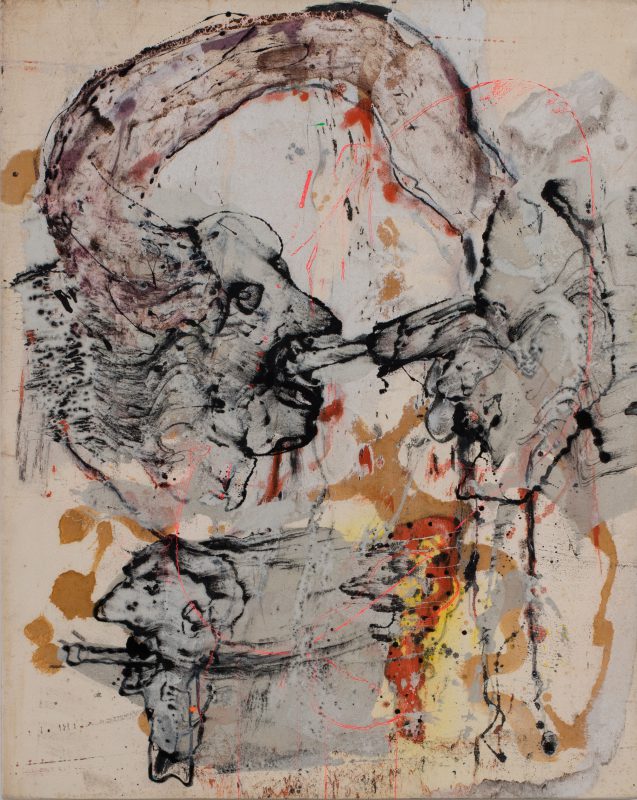

Ed Moses, Ranken #3, 1992. Oil, Acrylic, and Shellac on Canvas, 60 x 48 inches. Courtesy of Albertz Benda and The Artist

Under this logic, the likenesses present in the work then might ostensibly be part of a schema (as in Rose #6, with the flowerlike forms dictating the piece’s composition), or they might not (see Ranken #3, a 1992 work finding strange similarity with a Rorschach). Regardless, the content of the work—its texture and depth—is not contrived nor constructed (or maybe not even created) but instead revealed both through the medium as well as through the act.

Moses is a bee in Rose #6, buzzing from floweret to floweret. Each hashmark an ode to an action, an incantation, an appeal to a blind but instinctual telos. But he is also a master of death in this work, subject not only to a paradoxical loss of self found only in an act of repetition but also the author (or soothsayer) of death’s inevitability. (The hip of the rose once devoid of pollen, shrivels to a blackened mass—the seeds scattered.) Both the rose and the bee are there only to carry the pollen, and the characters (as interpreted as well as embodied by Moses) then find themselves bound up in a ceaseless cyclicality.

But Moses’s attention to process also becomes an attention to its termination. For how could a finite being really understand or embody the continual, the perpetual, the infinite?

Ed Moses, Rose #6, 1963. Graphite and Acrylic on Chip Board, 60 x 40 inches.

For Moses sometimes this limitation seems to resolve itself with the edge of the paper (as in Rose #6). But in others, this frontier appears to be addressed through the (paradoxically futile) combat of the limit itself—through the archiving of action.

What distinguishes Moses from other prominent abstract expressionists, or his near-contemporaries found in the New York School (and most specifically Pollock, to whom he is often compared), is this notion of archive—of slowing gesture down to a sub zero state. Gesture and abstraction for Moses are not indicative of a psychosexual drama of sorts, nor a fighting for a still active/still present status. Instead, through abstraction, Moses is making himself a mirror, a body of work that upon completion he can look at to affirm his existence. His motion both subjected to as well as trapped within time.

This reading of memory, impression, and fossilization emerges out of the medium itself: the flatness of the surface, the diluted paint seeping into unprimed canvas, or (as in Ranken #3) the singularity of a gesture—one elongated quivering vertical brushstroke, left to be looked at.

It is then this zeroing in on one moment, one action, that gives Moses’s paintings their paradoxical quality, an airy maximalism, a resonant vacuity, a bloodied bloodlessness. But, it is also this relative stillness that gives the painting’s their strength—the ability to maybe not achieve timelessness (with the medium itself—the canvas, stretcher bars, paint—being subject to time’s perpetual droll), but at least through visual metaphor point to the possibility of interminability, of stasis.

A point hovering just above absolute zero. A mark saying, I was here.