It is hard to believe that only a few years ago people around the world couldn’t conceive of African digital art. Perhaps it was out of sheer ignorance, or a long history of a continent misunderstood, but there was a widely held assumption that Africa had been left out of digital life. If you Googled “Africa” 10 years ago, you would probably have come across: a map of Africa, The Lion King, wilderness and safari photography, and “poverty porn” with its attendant images of hungry children, war, disease, and strife. But inside roadside Internet cafes, or in local stores where you could purchase data bundles, a quiet revolution was taking place.

Internet technology, like everywhere else in the world, was radically transforming culture. Kenyans formed informal communities like #KOT—Kenyans on Twitter—banding together in conversation over the latest scandal. In Nigeria, MP3s were downloaded and shared illegally, creating pop sensations that would soon take the global stage—artists like P-Square and D’Banj. Traversing through the silicon savannas, digital explorers mounted their curated discoveries on sites like Pinterest or Tumblr. Every month, it seemed like a new blog was formed: Africa is A Country, Another Africa, Nigerian Nostalgia, Afro-Punk, Everyday Africa.1 Catchy phrases like “Africa is Now, Africa is the Future,” developed and solidified within our online consciousness. The rise of an online Africa was also marked with the rise of global exhibitions around the world, from the 2015 Venice Biennale curated by an African, Okwui Enwezor, to the 1-54 Contemporary Art Fair, in New York, and now more recently the Armory Focus: African Perspectives exhibition.

A New Canvas For The African Artists

African artists and designers took note of the sudden push online, and embraced social media platforms. For artists like the Kenyan musical group, Just A Band, digital culture was seductive . . . you could be in touch with anyone, everywhere, all at once, in real time. For Just A Band, the Internet was a distinct way to connect to those of a similar tribe—not bound within geographical restrictions or political affiliations, but rather tech savvy Millennials who had grown up with global media phenomena like Daft Punk, Naruto, and good old Clint Eastwood. Digital technology and Internet accessibility lead to their creation of Kenya’s first viral video “Ha He” in 2009, a music video depicting their Kenyan revision of Dirty Harry’s phrase “Make My Day.”

For culture and tastemakers, Instagram facilitated art directors like Rharha Nembhard (@dronegoddess) and new imaginings of African culture that could be shared, tweeted and liked across the globe; African identity was fusing with other cultures and extending the African diaspora to new territories.

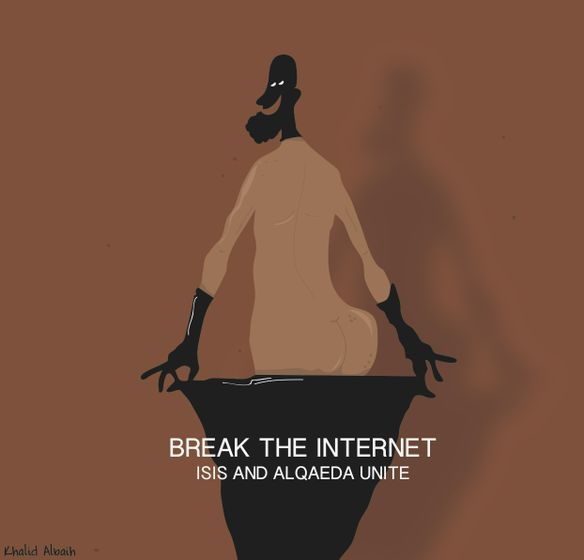

This digital cultural revolution extended past the visual and into political discussions. Artists participated in a new medium by openly criticizing government institutions as well as interrogating the rise of social media platforms in their countries. Khalid Albaih, a Sudanese political cartoonist, rose to prominence during the early stages of the Arab Spring protests in 2011. Albaih predominantly creates his cartoons through digital media and shares them through social media. The Internet affords artists like Albiah a way to speak out against political regimes and openly criticize religious institutions in ways that would have once cost him his life in Sudan. Albaih is just one of the many African digital artists who understand the influence of digital media but are also skeptical of the medium.

Khalid Albaih, Charity #Sudan, 2014. Courtesy of the Internet.

Khalid Albaih, #BreakTheInternet #ISIS and #AlQaeda Unite, 2014. Courtesy of the Internet.

The Legacy of Imperialism and Colonialism on the World Wide Web

In 2011, the a United Nations report declared “that disconnecting people from the Internet is a human rights violation and against international law.”2 While the net neutrality debate rages on, Africa is often left out of the discussion. Dubious initiatives from Facebook, like Internet.org, hope to “bridge the digital divide” by providing regulated “free Internet” to everyday Africans. Yet, the Internet in Africa will never be neutral. The historical, social, cultural, and economic implications are felt as digital users pay the high cost of fiber optic undersea cables that reveal the imbalance of power. Sub-Saharan countries dish out high premiums for access to international pipelines.

The true implications of the digital divide is not lost on South African digital art collective NTU. For the collective, the discussion of Internet accessibility goes beyond a more connected Africa. Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Nolan Oswald Dennis, and Tabita Rezaire see the Internet as a highly problematic medium. NTU describes itself as “an agency concerned with the spiritual futures of the Internet,” dedicated to “provide decolonial therapies for the digital age” and to “enhance intersubjective virtual user possibilities.”

In an interview with OkayAfrica, Tabita Rezaire put it bluntly: “The Internet is exploitative, oppressive, exclusionary, classist, patriarchal, racist, homophobic, transphobic, fatphobic, coercive and manipulative. The Internet reproduces IRL fuck ups i.e. western racial, economical, political, and cultural domination, legitimized behind the idea of modernity and technological advancement. It promotes occidental hegemony; brainwashes its users, whitewashes information, and is an active tool of surveillance, propaganda, censorship and control.”3

Tabita Rezaire, Afro Cyber Resistance, 2014.

The Future of African Digital Art

In 2016 there are 120 million Facebook users each month in Africa. The majority of them come from Nigeria (15 million), South Africa (12 million) and Kenya (4 million). South Africans surpass the global average time spent on online social networks with an average of 3.2 hours while the global average is 2.4 hours. These statistics translate to the change in perceptions of Africa. No longer do you just see The Lion King while searching for African content. Today, digital art is a highly embraced medium. From software to hardware, digital artists are experimenting with technology. From augmented reality and virtual technology to conceptual art and 3D gaming, the digital revolution continues.