Terence Koh: Bee Chapel

Andrew Edlin Gallery

212 Bowery New York, NY 10012

May 21 – July 1, 2016

From the outset, Terence Koh’s Bee Chapel at Andrew Edlin is a bit mystifying, imbued with mysticism of a strange variety. A container of hot tea sits on a rough wooden shelf just in front of the gallery desks. Mugs with humorous or politically motivated slogans line the shelf below. Opposite the desk is a bookshelf lined with novels, self-help manuals, and textbooks on diverse subjects from “The Hindus” to the history of dance and Einstein. Social reform pins from the past few decades—including some advocating for Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders—overwhelm a drab suit hanging from the ceiling so that it appears the suit has suffocated its former owner, forcing him to slip out of the grip of sociopolitical obligations. A hexagonal cutout in the wall has been lined with wax that looks at first like insulation. Inside this alcove lies a dead yellow bird. Its legs are tightly crossed, eyes shut. Just behind the front door, in a hanging patchwork quilt, a waxen newborn baby lies with a pin on its chest reading, “Fear Nothing But Fear.” The baby is covered in dead bees; it also holds some in its lifeless hand. If not for its placement at the entrance, the cradled baby would have felt more reverential than disturbing.

Terence Koh, bee bee, 2016. 12 x 8.5 x 5 inches (30.5 x 21.6 x 12.7 cm),

beeswax, button, natural died bees, american quilt, human skull. Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

Amidst this spatial collage, the most prominent element in the room is a series of hanging glass boxes held together by larger wooden frames, resembling beekeeper slides. Each holds a number of dead bees, and is also filled with miscellaneous tokens of cultural significance or quotidian life: a Nina Simone cassette; postage stamps depicting world leaders and religious figures from India, Germany, Iran, Syria, America, and Russia alongside stamps of ET and illustrated ducks; black and white mugshots; curry powder; honeycomb fragments; and a waxen human ear. In another frame, the glass has been shattered—not by a rock or sharp object, but rather by a flower stem.

Terence Koh, in persia there is a garden that apples are dreaming now, 2016. 31 x 25 x 2.75 inches stamps, glass lanten slide, tumeric, pollen, beeswax, baby snake skeleton. Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

All along the floor underneath these hanging cases are flags, posters and cardboard signs, all reading NOW. These are remnants of the show’s opening, when visitors were asked to parade into the gallery carrying any sign that read “NOW.” Because most of them are clearly homemade, the signs seem to add the present moment of unrest and activism into Koh’s catalog of social history represented by his framed collages.

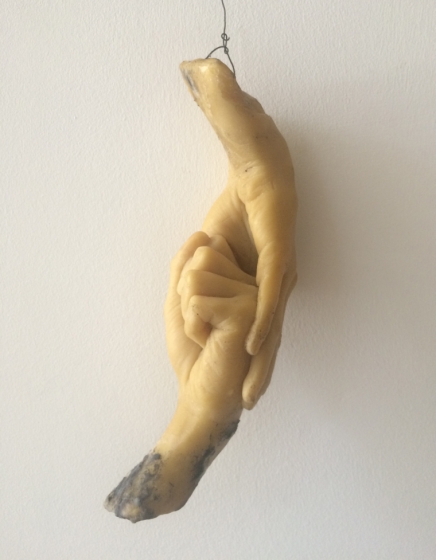

Hanging from the ceiling in this first space are also sculptures, presumably made of wax, of clasped hands, as if one hand were pulling up the other to prevent it from drowning midair. The hands are smeared with soot and dirt. They are incomplete, severed at the wrists. Though they are literally disjointed, the elements of this room are tied together by moralistic or religious themes of salvation, change, and devotion.

Terence Koh, the wisdom of thieves, 2016. Beeswax, ash. Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Clear plastic piping hanging from the ceiling leads visitors back into the curtained rooms beyond. Before entering, one must read a posted sign: “in the next room sleeps eve the apple tree.” Below this title are explanations of the various sounds in the show, which did not seem intentional until now. The sounds are combinations of recordings of bees, the cosmos as transmitted to a community college in Hawaii, two black holes colliding as recorded by NASA, and vibrations of flames from a burning candle in a room beyond. The sounds are all apparently being retransmitted into space. “To” and “be'” are misspelled as “too” and “bee” throughout this text; others are also misspelled.

Terence Koh, bee chapel, 2016. Installation view at Andrew Edlin Gallery.

Eve the apple tree turns out to be a real tree. Her roots are bandaged as if they were bleeding human limbs. Her fruit has fallen and is now rotting underneath her branches on the dirt floor. She lies horizontally. She is not the only thing lying horizontally in this room. Walking further in, one notices along the far wall what might be a body. Because the entire room is dark, lit only by a single red bulb, it is easy to believe that this is a corpse. It is in fact an astronaut suit studded with more pins, lying on a sort of wooden stretcher. From the legs of the suit protrude two waxen feet. From the sleeves protrude two waxen hands. The helmet shields the face. Its reflective surface makes it difficult to stare at; one feels watched. Walking around the room, one can feel the differences in vibrations. At the far corner near the astronaut, the air feels tense. Closer to the entry wall, a large black box emits dense vibrations. The sound and light create an atmosphere similar to that of La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela’s Dream House, but the dirt floor, astronaut body, and once-live tree give this space a more disturbing atmosphere. It could be occupied as the gathering point for the culmination of a ceremony. Is it alive? There are probably bugs in this dirt, maybe even shoots of new life. The vibrations are life, as the poster said (“the bees vibrating, the tree vibrating, we are all vibrating! we are all made of light!“).

Terence Koh, bee chapel, 2016. Dimensions variable, beeswax, earth, wood, stone, bees. Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery.

In the final, farthest room, following a hallway behind a third black curtain, is the eponymous “bee chapel.” A sign posted on a stick just outside this room instructs visitors to the chapel to remove their “shoos” before entering and proceed individually. Again the room has a dirt floor, but now the dirt has been stacked up to cover rocks and wood sculpted into stairs. At the top of the stairs is a strange yellowish hut made perhaps of papier mâché. The sound of bees is absent here as an audio track but is replaced by the presence of live bees. They trickle in through a clear plastic pipe that leads from the outside of the gallery into the yellow dome. Enter the chapel and one will literally be in a hive. The bees are separated from the visitor by metal mesh, but their bustling noises and the sickly sweet smell of wax and honey overwhelm the space. It feels unreal, as if one is entering a child’s book.

Terence Koh, bee chapel, 2016. Installation view at Andrew Edlin Gallery.

On the ground around this hive, little shoots poke up from the dirt. Here is new life. Now it is clear that these rooms have been a progression from death (of Eve) to the beginnings of life (a flame) to a new habitat where life may prosper. Leading up to the chapel, the visitors form a line, a new sort of cluster or hive. With hushed voices, they enter and exit slowly, lingering and appreciating their peaceful coexistence with the bees.

Terence Koh, crickets falling the sky laugh, 2016. Courtesy of Andrew Edlin Gallery

Returning to the beginning then, what to make of the library, tea serving, postage stamps, skulls and hands? While that room feels consciously playful or unserious, the rooms beyond sober the viewer until they feel compelled to proceed silently. Is this only because of the darkness? However spectacular it is, the show is about more than novelty. Beginning with a small piece of life, an animal we may feel unconnected to or even disturbed by, the artist sets up an experience that may be universally internalized. It is as if Koh has created a new religion, first outlining an origin story for the primary symbols and objects of devotion with his signpost about Eve while offering corresponding devotional terms, then providing a path to enlightenment that helps one understand the origin story and feel connected to the bees that hum at the thriving heart of the religion. Perhaps the collages of postage stamps and faux-activist posters were meant to introduce the sort of sociopolitical rivalry that these consequent rooms assuage with their sacred hum. Take this with you, Koh seems to say. And I do: outside the gallery, on a nearby green construction wall, someone has spray-painted, “NOW.” The world feels too present and I want to return to that chapel, to bee with the bees and participate in the transmissions Koh sends into the universe.