17 QUESTIONS with Guy Overfelt

“I’m a card-carrying member of the In Too Deep Club. I’m in it for life and

there is no escaping.”

With questions from: Jana Blankenship, Constance Lewallen, Stephen Hendee, Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson, Joseph Del Pesco, Carlo McCormick, Tony Labat, Oleana Jacobson, Larry Rinder, Janet Bishop, Paul Kos, Kenny Schachter, Jackie Perez Gratz, Howard Fried, Alex Frankel, Tony Serra & Frank Kozik

#DARKSIDE (after Hendee), 2012 Steel, Roll Cage Paint and Two-way Plexiglass Security Mirror 96 X 75 X 65 inches″

For this addition of SFAQ, we invited notable artists, critics, curators, the children of curators, musicians, art dealers, and civil rights attorney Tony Serra, to ask artist Guy Overfelt a series of questions about his life and work.

Guy Overfelt is a conceptual artist who is perhaps best known for his burnout performances which utilize a 1977 Trans Am as both a performance object and a printing press for projects that reference emotional and economic burnout, class division, power dynamics, and the post-modern industrial complex. His other projects include a life size inflatable Trans Am, 30’ x 25’ inflatable smoke, and event based social sculptural projects that range from giving free beer to the public, allowing himself to be shot with a taser gun, producing and promoting heavy metal cover band concerts, and taking on the identity of a stock broker for over a year, requiring a change in his hairstyle and address.

His work has been exhibited internationally in galleries and museums, including the Oakland Museum of California; Guangzhou Triennial, China; St. Mary’s University, Halifax, Canada; The Havana Biennial, Cuba; Ronald Feldman Fine Arts, New York; Jack Hanley Gallery, San Francisco, and White Columns, New York City. His work has been acquired by the Berkeley Art Museum Collection and the JP Morgan Chase Art Collection, as well as private collections. Reviews and features of Guy’s work have appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Art Net, Art Papers, Index Magazine, Paper Magazine, Time Out, Kobe Japan, Time Out, New York, Boing Boing, SF Guardian, Surface Magazine, the San Francisco Chronicle and many other publications. Guy’s work has also been featured in the documentary film ‘Burning Rubber’ on the Bravo Channel.

Guy’s work can currently be seen in San Francisco at Ever Gold Gallery, and Eric Firestone Gallery, East Hampton, NY. His upcoming solo show #blacklight at Ever Gold Gallery opens in October 2012.

Paul Kos: Artists do what they do for a myriad of reasons. I would like to ask a basic question. Your work has many sources, some environmentally determined, some perhaps genetically, and some perhaps personal responses to your family history.

After you were conceived and born, you were named Guy Overfelt. What are the roots of the name, “Overfelt”? Why “Guy” ? After whom?

Guy, please tell us about your past in detail and where you are going so quickly.

( A side note: when I was a kid, the only person named Guy I had ever heard of was Guy Lombardo, famous for slow, slow, waltzes and Auld Lang Syne. He was the onomatopoeia of New Year’s Eve. And once as a 1955 Chevy moved slowly down the street, someone in the car yelled, “Hey guy!” “Yeah you!” “Guy, where is the closest Ethel?” )

My first name is actually Terry. My parents were both named Terry, and they named me after themselves, so naturally, I adopted my middle name Guy. My name confuses some people, and it’s confusing for me sometimes when people lean out of car windows and say things like “hey guy, do you know how to get to Starbucks?” Sometimes I think they actually know me. When I order a non-fat vanilla soy latte with shaved chocolate, I usually tell the person behind the counter that my name is Bob.

I haven’t geeked out on my genealogy much or wanted to pay for a membership to ancestry.com to find out, but this is what I learned from google: Of English origins, the family name includes Over, Overs and others. First found in Cheshire where they held a family seat as the Lords of the Manor. A family seat was the principle manor of a medieval lord, which was normally an elegant country mansion and usually denoted that the family held political and economic influences in the area. The Overfelt surname is generally thought to be a habitational name, taken on from one of several places named Over, or Ower in Britian, such as Over in Cambridgeshire in Cheshire and in Derbyshire. These place names are derived from the Old English “ofer” meaning “seashore” or “riverbank”. This would now explain how my Aquarian astrological mythology and genealogy have created this unconscious desire to live in close proximity to the ocean. Guy is of French origin and is also slang for man, dude, bloke, mate, lad, chap, fella, etc. It would seem that I have been named after Guy Fawkes (explaining why I find myself expressing ‘FAWK’ much of the time) and would generally explain my life as man/guy/dude living near the ocean saying ‘what the fawk’ about current socio-economic & political conditions. Thanks Paul! I didn’t realize any of this, until now. It makes complete – onomatopoeia name-life forming – sense, but I’m sure that my “every man” name, the casual slang for manhood in someway shaped the way I think about masculinity which has had a great impact on my work.

"untitled (Tony Labat shot me in the face with a taser)", 1998, Video, color, sound, 7 seconds, dvd edition of 3.

Jana Blankenship: When did your obsession with cars begin? In light of your work that addresses car culture and the American Dream, what kind of wheels do you have? What does that car symbolize to you?

I use cars as a conceptual tool for exploring undercurrents that shape the slick packaging of the American Dream, despite its often painful and messy human reality. Burnout, for example, has been a long running theme in my work. I have a 1977 Trans Am that I’ve used as a kind of talisman to explore a continually changing sense of the American Dream.

I wasn’t interested in car culture until graduate school, although I grew up around car and motorcycle subculture. My mother raced her 1970 Nova SS when I was a toddler, and my father was a member of the Hells Angels. My lack of interest in car culture as a child may have been my silent rebellion and a way of unconsciously creating observational distance within my parents’ involvement with car and motorcycle culture.

I began working with a 1977 Trans Am as a way of addressing an aesthetic class divide that I view as heavily mediated by marketing. The 1977 Trans Am achieved record sales levels for General Motors after it was featured in the 1977 Hollywood film Smokey and The Bandit. Working with the Trans Am enabled me to reach into something that had emotional resonance for me that married something poetic with theory. It allowed me to acknowledge and explore the class dynamics I was born into as they related to marketed messages of power and masculinity. In my work, cars represent a common connection between male class struggle at its most basic level; a desire for power symbols, and the aesthetic markers of status defined by education level, region and situational influences.

"untitled (My 1977 Trans Am crushed into a cube)", 1998-2010. Crushed automotive steel. 24 x 24 x 24 inches. Courtesy of Ever Gold Gallery

Constance Lewallen: What is the thread that connects your works?

I’m interested in our collective human condition and the poetic dynamics that shape personal and collective politics.

Stephen Hendee: You’ve told me that early on you enlisted in the military and were assigned intelligence work. A number of notable visual artists have done military service. How has this influenced the production of your art and the field of advertising that you’ve also found success within?

If I told you, then I’d have to… The intelligence work I did for the US military wasn’t entirely by choice, and I was still a teenager, so I went in with my eyes partially open, with a rebellious spirit, and an awareness of military manipulation. My work within advertising and the military has made me hyper aware of the ways in which human behavior is monitored, mediated and controlled.

Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson: Surveillance has long been a strategy in, and subject of your work, pre-dating the wide spread use of such technologies today. How has mainstream adoption of surveillance affected your approach?

I cope with feeling powerless in the face of invasive and seemingly inescapable surveillance through toying with the absurdity of a culture that often prefers not to challenge breaches of civil liberties.

The integration of various levels of surveillance in everything from tracking web activity monitoring of the programming individuals watch on cable and the commercials they skip; email keyword tracking used to direct advertising, and free reign wiretapping, all seamlessly bleed across our civil liberties and threaten rights to privacy.

When working on a project, I create meaning through context, employing humor and allowing for chance operations to reveal my thinking as it relates to forms of social control; hopefully challenging and shifting perception to create a dialog with the viewer.

"Ever Wash", 2011. Social installation of a fully functional free laundromat, at Ever Gold Gallery, SF. Courtesy of Ever Gold Gallery.

Joseph Del Pesco: Can you tell us (in as much detail as possible) what it was like to work with Tony Serra and what he thought about your act of involving him in your project?

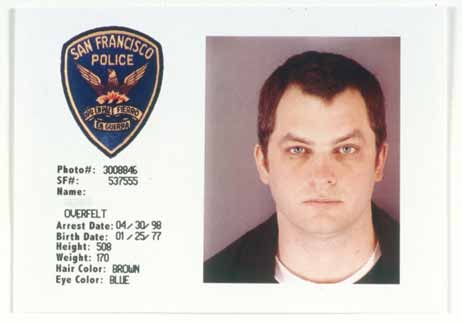

The project you’re referring to is the Burnout Project, and my subsequent arrest and trial at San Francisco Hall of Justice which became a performance piece. My performance involved hiring the renown courtroom sketch artists Walt Stewart and Vicky Behringer to document the trial. Walt and Vicky illustrated the trials of OJ Simpson, the Enron Scandal, the Michael Jackson Arraignment, the Scott Peterson trial, Anderson Trial, Unabomber Theodore J. Kaczynski, Corcoran Prison Guard Trial, serial killer Juan Corona, Patricia Hearst, Bill and Emily Harris, Angela Davis, Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, Howard Hughes’ will, the Charles Manson trial, and a deposition in the Iran-Contra scandal. I also turned my citation into a printed invite, inviting guests to witness the court proceedings as a performance.

I was incredibly lucky to have had Tony Serra defend my case. For those who don’t know who Tony Serra is, he is a civil rights attorney who is probably most famous for defending rights of the Black Panthers, the Hells Angels, Earth First, and the New World Liberation Front. He has a personal relationship to the art world through his brother, the artist Richard Serra. Tony felt that through my case, he could address what he thought were violations of freedom of speech and expression. Serra and his team of attorneys Shari Greenberger, Omar Figueroa, and Shannan Dugan worked on the case together.

Although Tony was arguing for my freedom of expression, he planned to use a defense tactic he had used when he defended a fire-breathing circus performer for DUI. In the fire-breather’s case, the arresting officer hadn’t believed that he actually was a fire-breather, or that alcohol was an essential part of his act. Tony asked the fire-breather to perform his act and then took a breathalyzer test for the jury who came back with a unanimous not guilty verdict. Tony had planned for me to perform a burnout in the parking lot in front of the court house so that my jurors could see that I posed no threat to public safety, but my case was ultimately dismissed before it came to trial.

After many months of meetings with the District Attorney and the Judge, Omar Figueroa uncovered that the illegality of burning out was found to be an opinion of a California judge in 1961. That judge thought that burning out/loosing traction ought to be against the law, but his opinion was never actually made into law.

Carlo McCormick: I think your primary debt to the lineage of San Francisco conceptualism is that you appreciate how funny they all allowed their work to be, how they did not take themselves as deadly serious as other conceptual art scenes. Would you agree with this assessment, and what would you say you have learned from that bay area tradition?

Yes, my work is highly influenced by San Francisco conceptual artists who I imagine were influenced by politically motivated/protest based pranksterism. The ability of those artists to transcend a staid, accepted framework through irreverent and seemingly absurd action is what compelled me to become an artist. I fear I may sound too Northern California, post-new age, crunchy in writing this, but that approach to transforming perspective is a hopeful act. It’s an approach to life and work that enables me to continue to make art and it’s something that I continue to strive for and learn from.

Tony Labat: What is the difference between a reference and a rip-off?

This is a loaded question for me, and I think that the idea of a creative commons has confused some people who don’t believe that they need to credit their influences. A rip-off is stealing without crediting the original source. (I don’t think this is what Picasso meant when he said “great artists steal.”) If you rip-off the work of your contemporaries (or other generations of artists) and present work that is a one to one copy or close proxy, aesthetically or conceptually, without crediting the person who originated the work, it’s a rip-off. Unfortunately, artists rarely have the resources or connections to successfully challenge this kind of plagiarism that is currently rampant within the contemporary art world among socially connected and often financially comfortable artists.

Oleana Jacobson: How did you come up with making a tar ball?

When I made burnouts on paper, the tires acted like duel snow maker machines, but instead of snow, tiny pieces of rubber from the spinning tires accumulated on the street. When I saw the piles of rubber that looked like black snow, I started making black rubber snowballs.

*I credit David Ireland’s hand made concrete Dumb Balls, as work that may have enabled me to think of those burnout balls as a valid conceptual art object.

Larry Rinder: You have used Joseph Beuys’ term “social sculpture” to describe your work. If you had a chance to meet Beuys, what are three questions you’d like to ask him?

I would only ask Joseph Beuys two questions.

Social Sculpture was a term created to illustrate Beuys’ idea of art’s potential to transform society. It includes human activity that strives to structure and shape society or the environment. Bueys’ idea of a social sculptor is an artist who creates structures in society using language, thought, action, and object. Beuys said that “Everyone is an artist,” so I would ask him why he felt it was necessary to make art for galleries and museums.

I would also ask him to recommend a good felt distributor.

Guy Overfelt, “untitled (study for burnout lenticular)”, 2012. Unique C-prints. 8” x 10” each. Courtesy of Ever Gold Gallery.

Janet Bishop: I was lucky enough to participate in the delicious and really interesting dinner piece you did at Four Walls, back in 1997. How did you come up with the idea for that and were there any big surprises as the evening unfolded?

Thank you again for coming to that dinner. I greatly appreciate the bravery of everyone who agreed to participate in that project, which was a behavioral experiment within the art world microcosm of San Francisco. The piece was modeled upon the rules within Emily Post’s Book of Etiquette and came from a desire to play with perceptions of gallery space, its function, and art world role-play between dealers, curators, critics, collectors, and artists.

In many ways it was a collaborative project that organically evolved with the amazing gallery partners at Four Walls, who contributed their personal experience, thoughtfulness, and labor to the project. There was a sweet youthful energy that everyone involved with designing the dinner literally brought to the table. The dinner menu was developed and planned by myself, Julie Deamer, her gallery partner Suzanne Stein, and chef David Becker’s professional guidance. All the food was prepped in Julie’s kitchen at her home and then brought to the gallery where, four massive leaning walls created an arena-like environment for a long, elegant dining table with seating for thirty.

While serving there were several mishaps. I accidentally spilled hot soup in Paula Anglim’s lap and overfilled Howard Fried’s wine glass so that Hess wine spilled over his hands and the white table linen. Everything else I’ve either forgotten or blocked out, so I hope nothing more than that happened.

Kenny Schachter: Are cars art? Why cars and what’s your favorite, do you identify with a particular marquee and model? When was such an impression formed?

Cars are art although the cars I use in my art are not meant to be “car art.” In my work, the car is a conceptual device. I have used a Trans Am in my work over the past 16 years, but I can’t commit to a favorite car make or model. There are so many amazing cars to choose from that span epic periods and countries.

I didn’t get into car culture until I was in my twenties, but I’m sure I was influenced by my parent’s taste, so many of my favorite cars are American muscle cars: The first muscle car, a 1949 Oldsmobile Rocket 88; a 1955 Chrysler C-300 (I just saw one a few months ago, completely restored and being driven on the street); a 1953 Corvette with classic red leather interior; The Dukes of Hazzard’s 1969 Dodge Charger R/T; Steve McQueen’s 1968 Ford Mustang 390 GT. A 2005-6 Ford GT. The AMC Pacer featured in the movie Wayne’s World; the 1955 Chevy which appeared in Two-Lane Blacktop and American Graffiti, and lives in San Francisco; the Tesla Roadster; a 1968 Dodger Super Bee; the 1966 Ford Holman & Moody 427; and of course, the 1977 Trans Am (with it’s symbolic phoenix hood decal) that became a cultural icon after it appeared in Smokey and The Bandit.

Jackie Perez Gratz: Why do you like fast cars?

Performance. Freedom. Speed. I’m a fan of stories about cars, movie car chases, and music about cars. The existential message within the films Two Lane Blacktop, Vanishing Point, and Mad Max woke up my teenage mind. I have memories of watching Tracy Chapman performing ‘Fast Car’ on television in 80’s for Nelson Mandela. My mom was once pulled over by the police for speeding in her hot rod, a 1970 Nova SS while I was a passenger, and that made me think my mom was a badass. I have tender memories of my dad, who died when I was in my early twenties, letting me steer his 1964 drag-race prepared Ford Falcon down the freeway at a 120 while sitting on his lap, and of hanging on to him for dear life as we tore through the desert doing 100+ mph on his Harley Panhead. A need for speed is probably in my DNA.Fast cars are symbols of freedom and revolution even though it’s all a smoke screen. They represent a double edge of interpretation governed by perspective.

Howard Fried: Favorite building material age 4; favorite food age 9; favorite building material age 14; favorite food age 19; favorite building material age 24; favorite food age 29; favorite building material age 34; favorite food age 39; favorite building material age 44; favorite food age 49; favorite building material age 54; favorite food age 59; favorite building material age 64; favorite food age 69; favorite building material age 74; favorite food age 79; favorite building material age 84; favorite food age 89; favorite building material age 94; favorite food age 99?

Favorite building material age 4; PINE WOOD. favorite food age 9; PINE WOOD. favorite building material age 14; CHROMOLY. favorite food age 19; PIZZA. favorite building material age 24; BRONZE. favorite food age 29; SUSHI. favorite building material age 34; RUBBER. favorite food age 39; STEAK. favorite building material age 44; CARBON FIBER. favorite food age 49; LAMB. favorite building material age 54; TITANIUM favorite food age 59; MUSHROOMS. favorite building material age 64; PLASTIC. favorite food age 69; COCONUT MILK. favorite building material age 74; RARE EARTH MAGNETS. favorite food age 79; KIMCHI. favorite building material age 84; BRAZIL NUTS. favorite food age 89; GINGER. favorite building material age 94; BRAZIL WOOD. favorite food age 99; BRAZIL WOOD.

Tony Serra: Why must art at one level at least subserve political reform?

I don’t think art necessarily has to work in the service of political change. There is a lot of good art that isn’t made with the intention of supporting political change, and a lot of art that is made with an intention to promote political change that is heavy handed and overly intellectualized to the point where it reads as a dry academic exercise that doesn’t surprise or challenge.

It is wonderful to see work that challenges expectations, jars the senses, is irreverently funny, or feels poetic because it resonates on an esoteric and human level.

I believe that individual creative acts that remind human beings of our humanity are politically subversive acts in themselves, whether or not they carry an intentional political message.

Alex Frankel: You are outside of your studio or home when a fire threatens to engulf the building. You have one minute to run back into the burning building and grab something. What do you grab and why?

I live in a wooded area and this is a very real possibility so I’m glad you asked this question Alex.

Without a doubt I would grab my prized Hummel collection. I have collected Hummel figurines since boyhood. They are my passion.

I have hundreds of them, so I’ve made small harnesses for each of my ten cats that hook onto special rolling shelves in my display case.

Sometimes when I’m feeling bored with making art or scanning for new figurines on ebay, the cats and I run fire drills. Sometimes they fall out of line and things get a little chaotic, but really, don’t believe what they say about herding cats because I feel confident that when the time comes, my collection will remain intact so that my future son can enjoy them as much as I do.

Frank Kozik: Is it one obsession at a time, or is it a life-long arc? If the latter, is there an end or will you still create on life-support?

I’m a card-carrying member of the In Too Deep Club. I’m in it for life and there is no escaping.

Jana Blankenship is a contemporary independent curator based in New York City.

Constance Lewallen is an adjunct curator at the University of California, Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California.

Stephen Hendee is a visual artist and a professor at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore, Maryland.

Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson is the CEO and Director, Chief Curator at Aspen Art Museum in Colorado.

Joseph Del Pesco is a contemporary independent curator, art journalist and director at Kadist Art Foundation, San Francisco, California.

Carlo McCormick is a culture critic, writer, curator, and Senior Editor for Paper Magazine living in New York City

Tony Labat is a conceptual artist and a pioneer in the San Francisco performance and video scene.

Oleana Jacobson, is the daughter of Heidi Zuckerman Jacobson.

Larry Rinder is the Director of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive in Berkeley, California.

Janet Bishop is the curator of Painting and Sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in San Francisco, California.

Paul Kos is a conceptual artist and one of the founders of the Bay Area Conceptual Art movement in California.

Kenny Schachter is a professor, curator, writer, artist, collector, dealer and irritant to the art establishment on both sides of the Atlantic; he currently lives in London, England.

Jackie Perez Gratz is an electric cellist and vocalist for San Francisco metal trio Grayceon currently based in San Francisco.

Howard Fried is an American conceptual artist who became known in the 1970s for his pioneering work in video, performance and installation art.

Alex Frankel is not the lead singer of Holy Ghost!, the indie hunk behind NYC DFA buzzband, but

actually a San Francisco based writer, most notably the author of Punching In: The Unauthorized Adventures of a Front Line Employee, which presents some of the lessons he learned from his time working at several top brands including Starbucks, Apple, and Enterprise Rent-a-car.

Tony Serra is an American civil rights lawyer, activist and tax resister from San Francisco.

Frank Kozik is an American graphic artist who has worked with Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Stone Temple Pilots, the Red Hot Chili Peppers, Melvins, The Offspring and Butthole Surfers. He also runs Man’s Ruin Records, a media outlet and record label.

Contributing Editor Heather Sparks is a writer and conceptual artist whose work has been exhibited internationally. She has contributed to a number of publications including the Huffington Post. Her book: It Colors Your Life, A Coloring Book of Drinking and Smoking is in the pipeline.