Collecting, Compiling & the Construction of Cultural Histories

The act of collecting is an expression of one’s passion, be it butterflies or paintings by Monet. The curse of the assembler of cultural heritage is: What do you do with the accumulation while you are alive and what happens to the collection when you are deceased? This condition is aggravated when the collector is also an artist and able to develop a large collection with limited capital. Storage and the patience of loved ones are ongoing limitations, but in the long run the crucial concern is the future ability of the collection to generate scholarly research and exhibition, gaining an afterlife through increased exposure and influence.

Without detailed digital documentation, knowledge of the collection is doomed to disregard. To rectify this situation, the dedicated collector is forced to turn compiler, guiding a future audience towards the new directions that they have uncovered and where these directions may lead. Each new generation gains from those previous, adding something new to a progressing cultural history’s vocabulary. Without this guidebook, the more challenging works of contemporary art escape and defy understanding. In a raw, unformed state, they fail to attract institutional interest, subsequent scholarly research, and a renewed life after the collector’s departure.

The plight of the veteran mail artist is especially acute. Mail pours in from a Fluxus-inspired Eternal Network of artists producing correspondence, periodicals, artists’ books, original art, artists’ postage stamps, and collage, all incorporating numerous artistic mediums including photocopy, photography, painting, digital, audio, rubber stamp and other established and marginal mediums. Collaborative works are documented and distributed to participating artists, the active contributor receiving exhibition catalogs, “add and pass” works, assemblings (periodical-like compilations of original artworks), magazines, project reports, recordings of social, political and performative actions, as well as “tourism” reports for when two or more networkers meet.

Having mailed away works with little expectation in return, the choices for incoming mailings are endless. They can be recycled, framed, hoarded, sorted, cataloged, discarded, or ignored. Upon one’s passing, and without previous instruction, the remains of the collection are left to the discretion of a loved one’s bewildered whims. One of the aims of this column is to aid those mystified—both artist and estate—by what action to take concerning the cultural materials in their care.

Michael Leigh, England. From the collection of John Held, Jr.

Ray Johnson (c. 1955) postcard by William S. Wilson. From the collection of John Held, Jr.

Chicago Fluxfest 2013. Button. From the collection of John Held, Jr.

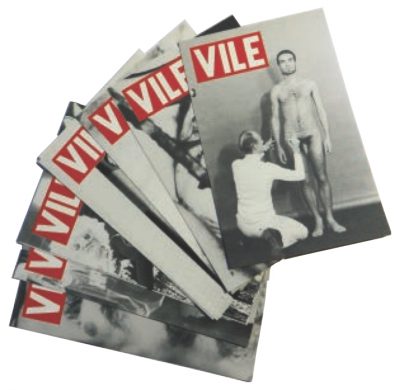

Promotional postcards, “VILE” magazine, Anna Banana, Editor. From the collection of John Held, Jr.

A well-developed history has been formulated within the field despite widespread art historical neglect. Duchamp, Dada, Fluxus, Ray Johnson, and assorted twentieth century avant-garde movements and figures, have cemented the foundation upon which mail art has thrived. Its DIY nature includes all and rejects none. In an analog state, postal interaction paved the way for the Internet in preparation for a digitally creative, open, international communication system.

Mail art’s greatest asset is the wide arc of its inclusion. Dismissed in the eyes of critics by its uneven quality, the totality of the network is its greatest strength and provides an incisive view into contemporary cultural concerns. There is no better or worse mail artist, only less or more active participants. The most instructive mail art collections are broad in scope, rather than, as collections routinely are, discretionary in nature. The Eternal Network is an encompassing system, fostering interaction across the divides of geography, language, and culture. The archive should reflect this welcomed diversity.

Decentralized Worldwide

Every six years for 30 years, the international mail art community has initiated a yearlong theme that examines a central concern of the medium. The initial project was the 1986 Decentralized Worldwide Mail Art Congress, which sought to stimulate practitioners into a discussion of the cultural relevance of mail art practice and its ramifications on their lives. Conceptualized by Swiss artists H. R. Fricker and Günther Ruch, the year brought together over 500 artists from 25 countries in 70 documented congress sessions.1

Six years later, the 1992 Decentralized Worldwide Networker Congress (organized by Fricker and Peter Kaufman) was called into being to encourage mail artists to dialogue with other networks (zine culture, artist books, print and music distribution, Neoism, Church of the SubGenius, and nascent telecommunication communities). The year of Incongruous Meetings (1998), Obscure Actions (2004), and Art Detox (2010), all organized by Vittore Baroni of Viarregio, Italy, perpetuated mail art’s yearlong inquiries.

When H. R. Fricker and Gunther Rüch first conceived of the 1986 Worldwide Decentralized Congress as a conventional and centralized meeting to discuss mail art, it was quickly modified to allow anyone, anywhere, to participate. It was felt that this best reflected the decentralized spirit of the medium, allowing open participation by anyone with an interest in the activity.

Social practice has been a fashionable avenue in art for quite some time now, and mail artists were among the first to tread this path on an international scale. Inspired by the Fluxus blend of art and life and espousing similar attitudes as those exemplified by the actions of Joseph Beuys, mail artists have extended their distanced relationships to meetings in which they interact in creative ways.

Mail art incorporated these ideas before the advent of the Internet, foreshadowing the widespread desire for timely, open, international communication, mimicking e-mail and the social media platforms yet to come. Like all advance scouts who venture into territories not yet trod by the populace, upon recounting their tales and making the unknown common knowledge, their services are no longer required. The analog postal system has been digitally superseded as the most popular timely, and economical means of information transfer, but its obsolescence has opened itself up to new possibilities.

In 2016, the mail art community focuses on the question of archives. Move Your Archives 2016 is the latest yearlong international collaborative project conceptualized by Vittore Baroni, joined by fellow Italian Claudio Romero in promotion and documentation through digital newsletters disseminated via social media, mailings, and participation at art events. Earlier in the year there were postings of archival materials on social media sites and rumblings of convened meetings, but it is Baroni’s wish that mail artists explore innovative, challenging ways in which to extend the avant-garde spirit to the Archive Year, citing Fulger Silvia’s attachment of thumbnail artworks to his substantial flowing beard.

Baroni’s invitation to participants states:

In decades of exchanges, many cultural workers have built up large collections of “physical” materials (original works, publications, complete projects, etc.). These heritages of ideas are likely to remain submerged and ignored, continuing to gather dust on the shelves or to languish in boxes locked in garages and attics. Many collections were destroyed, others were donated to institutions that are reluctant to put it to good use. In the thirtieth anniversary (1986-2016) of the Decentralized Congress, we invite you to revisit and revive your archive, making it available to others and trying new forms of encounter and collaboration with the most diverse collections, in order to promote a year of archives in motion.

Move your archive

Live your archive

Share your archive

Recycle your archive

WHAT: archives of mail art, visual poetry, copy art, small press, independent music, etc. but also creative collections of all kinds and epochs (stamps, bookplates, bottle caps, etc.).

WHEN: at any time during 2016, for any length of time, whenever two or more creative archives meet.

WHERE: in the studios and archives of artists, poets, musicians, writers, etc. In galleries, museums and other spaces devoted to the arts, but also in atypical spaces (squares, streets, shops, parks, etc.).

WHY: to put back in circle a hidden wealth of “concrete” materials and experiences. To not content ourselves with the great virtual emporium of culture made accessible by the Internet. To not have to wait another century before these materials are “historicized” by art critics and museums.

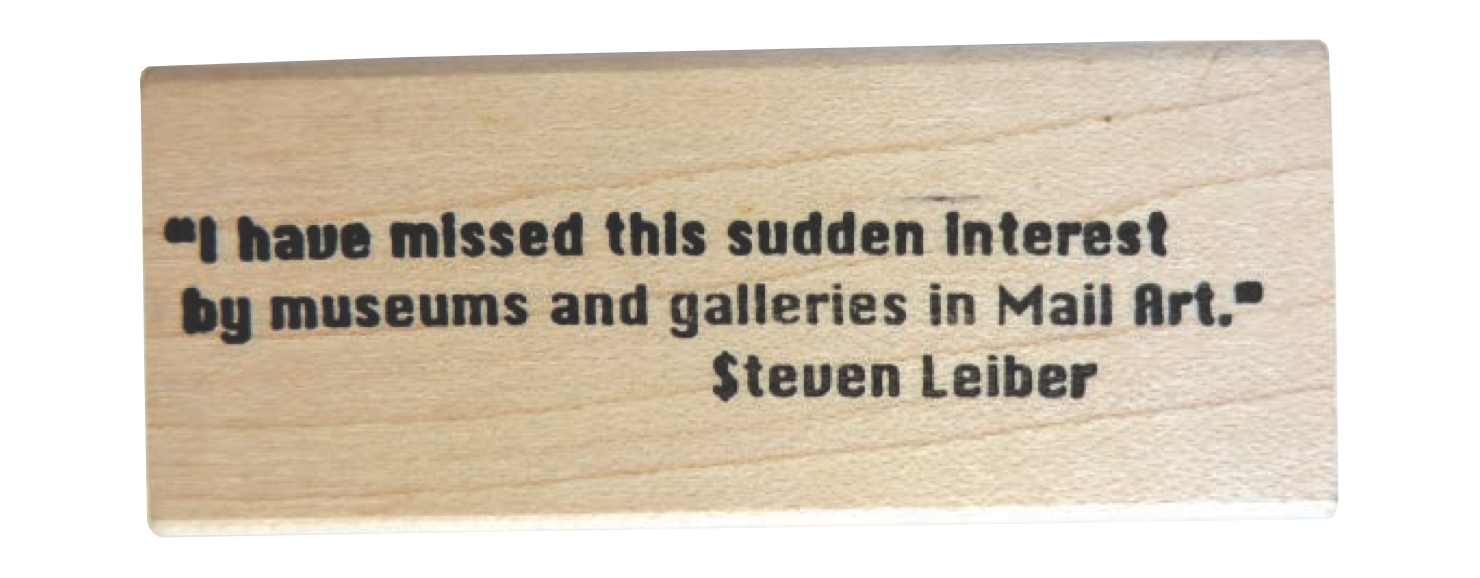

Rubber stamp in memory of Steven Leiber. From the collection of John Held, Jr.

M.Y.A. 2016 is a global, open and independent non-profit experiment, which promotes a different use of archival materials through meetings, sharing, synergies and group workshops. Document your contribution to M.Y.A. 2016 with photos, reports and in any way you see fit, then post the materials on the online diary in the Dododada website and you will be included in the final catalog.

The Mail Art Congress years have always reflected the network’s concerns of the moment. In the mid-1980s, when they were first established, mail art turned inward. Neglected by the mainstream, the medium was bereft of critical examination from without, and succumbed to introspection. The present day finds the aging practitioner of the medium—those in their 60s, 70s, and older—concerned with the disposition of decades-old correspondence, publications, and artworks. Continued institutional disregard forces the mail artist who is apprehensive of their collection’s future, toward an attentive comprehension of the situation and the formulation of creative solutions.

The next column in this series explores the disposition of collections of contemporary art currently dismissed by art museums and libraries as too challenging for institutional inclusion and some possible solutions toward rectifying the situation.