I met Puth Male last year, while volunteering at Sammaki, a community art space in Battambang, Cambodia where I now serve as an advisor. Male is a consistent volunteer with Sammaki, helping lead workshops for kids in Battambang province. Male first introduced me to Khmer Instagram through his own feed, sokthearith.p. His “mobile-photography” as he calls it, led me to invite Male to exhibit his Instagram photographs from June to August at Sammaki. Together, we selected the best work from his Instagram, and displayed the photographs, slightly enlarged but still in the (no longer mandated) Instagram square, on the gallery walls. The opening was well attended and Sammaki continues to sell his prints to this day. I believe this exhibition was the first exhibition of social media art in Cambodia, and without Male and Sammaki’s support, I wouldn’t know about this niche group at all.

My interest in Male’s work and Khmer Instagram comes from my interest in media from minoritarian groups. I am passionate about media produced by people international audiences usually ignore, a counter-colonialist gaze. I seek tactics for nourishing this gaze, for sharing it with the world in hopes of building new, more accurate narratives. This is a gaze honest to those so often ignored, because it is of their own making. I thought I found this gaze, a citizens’ media in Khmer Instagram. Maybe I was wrong.

@sokthearith.p

@sokthearith.p

As I wrote for SFAQ earlier about searching for empowered social media, sociologist Clemencia Rodriguez names, “‘citizens’ media” as those media that facilitate the transformation of individuals into “citizens.’”1 This isn’t to say citizens in the legal sense of the word, but rather persons, “defined by daily political action and engagement.”2 While this can mean bolstering relationships between citizens and politicians, more often, and especially at the beginning, citizens’ media focuses on building strong relationships amongst small local communities. It is a community dedicated to producing and sharing media for themselves.

In the West, representations of Cambodia are largely limited to horrific recountings of the Khmer Rouge, corruption and poverty, or at best, Angkor Wat. Cambodia is rapidly changing and far more complex. What’s exciting to me about Khmer Instagrammers is that they show a very different Cambodia—one international audiences are rarely privy to. While a very small subset of the Cambodian population, Khmer Instagrammers are capturing a life much like most urban dwelling youth today; we find fashion-keen kids listening to music, skateboarding, enjoying art, and experiencing all the chaotic anxieties and loves of youth everywhere. This is the opposite of poverty porn. After living most of a year in Cambodia, these are my friends, and while systemic differences sharply contrast our lived experiences, as people, there is more that connects us than divides.

While in 2014, only 26% of Cambodia was connected to the net, largely through phones, it was also experiencing the fastest growth in the region.3 International branding agency We Are Social reports that Cambodia experienced a 414% growth in active net users last year.4 While nearly half of those connected are on Facebook—as is the same for most of the world—Instagram is lagging behind.5 However, younger, more tech-savvy users—a small privileged slice of Cambodia—are quickly adopting Instagram. While spending most of my time in Battambang with artists, I’m largely surrounded by members of this small group.

With it’s mobile-first, light data-use, and emphasis on original photographs, Instagram is situated at the forefront of photography from Cambodia’s newly online population. Through these feeds, Khmer Instagrammers became a means for me to see a thin but exciting window of creative expression at the forefront of this change, and to watch how my friends in Battambang were similar to kids they followed in Phnom Penh and Siem Reap, the other two major metropolitan areas.

Upon beginning to scour Khmer Instagram, the photographs looked much like Khmer Facebook; candid photographs from parties; touching moments with partners: sharing meals with friends; vacation shots at tourist sites; and of course, selfies.6 “It’s mostly just selfies,” Male reflected with a hint of disdain as he first showed me Khmer Instagram. Cambodia has taken to selfies with a zeal I haven’t seen in any other country during my travels over the last two years, spanning three continents. While China certainly came close, and many more people owned phones, I’ve never watched people, men and women alike, spend more time taking more selfies than in Cambodia.

None of this is surprising; it’s standard social media culture wherever there is Internet access (and never forget that still remains a minority of the world). Throughout my travels, I’ve found people photographing their meals, themselves, their best friends and partners, and important life moments, and sharing them online. While a plethora of cosmetic differences can be found, the subjects remain remarkably similar. Maybe this is the greatest potential of citizens’ media; in a world where it’s so easy to divide people, citizens’ media can stand as a beautiful and comforting reminder of just how similar we are.

Maybe more unique

But of course, Cambodia is unique, and there are fascinating local differences when compared to other countries. Today’s urban centers like Phnom Penh, Battambang, and Siem Reap are experiencing rapid growth. While in 1990, the UN Capital Development Fund found that agriculture represented half of Cambodia’s entire GDP, the World Bank found that, since 1980, the percentage of urban dwellers has more than doubled.7 Furthermore, Cambodia’s urban areas now produce 60% of the entire country’s GDP. Many of my friends here are part of this group. Growing up in villages around Battambang, their proficient English and hard work allowed them to move into crammed apartments and go to university part time while working in the tourist industry to pay rent. Traditionally, a young woman would never be allowed to move out of the parent’s house prior to marriage, and women often move together, with sisters or female friends from the same town. This and countless other changes are coming with rapid urbanization.

While life in these urban hubs remain by no means easy, Cambodians there are finding higher levels of access to education, health care, jobs, and a more cosmopolitan worldview. With that newfound disposable income and a better education, Khmer youth are becoming increasingly connected to each other as well as the rest of the world, almost entirely through their phones.

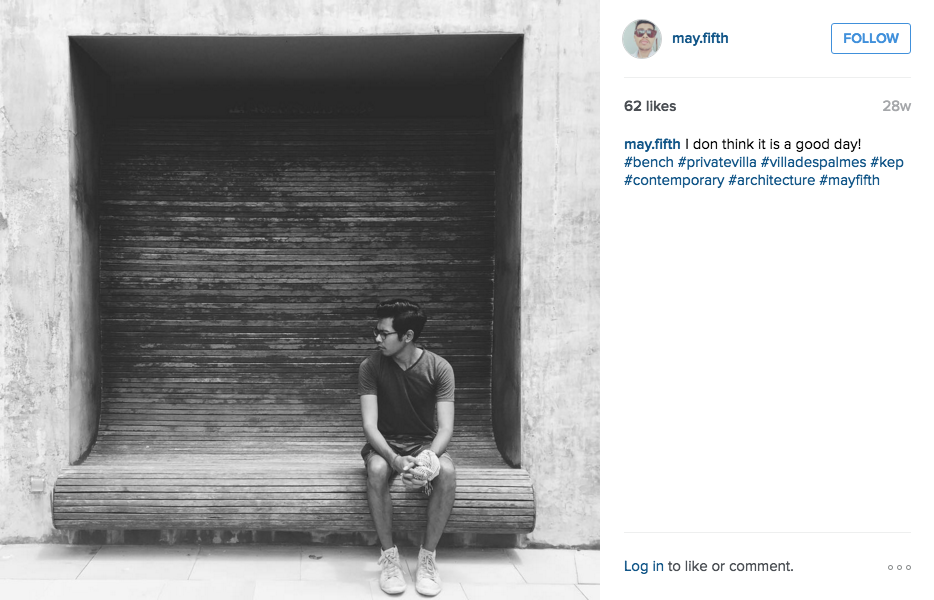

Documenting this aggressive urbanization is a key thread throughout Khmer Instagram. Photographing urban growth in Cambodia today is as much about architectural achievements as it is about construction sites. With his eye for bold lines and shadow, Oum Sothea, a professional architect in Phnom Penh, using the may.fifth handle, beautifully documents new and old buildings in Cambodia and the rate at which they are being built. Construction workers walk the tenuous scaffolding of new buildings few can afford.8

@may.fifth

@may.fifth

Interestingly, Khmer Instagrammers are also looking back, on the villages and nature distant from their urban neighborhoods. They document vacations in areas of natural beauty or visits to villages similar to those their families left behind. These are photographs of a life many of them never experienced. Male likes to go on long bike rides outside of town, searching for natural and pastoral beauty alone or with close friends or family. “These Instagrammers live in mad cities and try to escape from the busy life to find freedom with nature,” Male told me.

These are sunglasses-clad hipsters passing by farms only their parents know how to sow. Even still, the chaotic and congested city life draws urban Khmer back to an idealized, filtered, and hashtagged version of a recent agrarian past. Family trips to rural temples and farms are common. This is, however, a life increasingly few in Cambodia will know as many move to cities and forests disappear. Global Forest Watch found that since 2001, Cambodia has the fastest rate of deforestation in the entire world.9 This is particularly upsetting to many young Khmer I’ve spoken with. As Male reflected, “this is our land, our environment, our home, our breath.”

While both Facebook and Instagram in Cambodia are riddled with emotionally raw posts uncommon in day-to-day public life, Instagram appears to me to be more honest, at least in a few very important ways. Cambodia is a very religious and conservative country, and being openly queer is difficult. Perhaps due to the anxiety caused by Facebook’s context collapse—the result of placing your whole family, all of your friends, and a few strangers together in a public conversation—Instagram, with fewer users, less descriptive and deemphasized profile pages, and more easily hidden identities, is where some openly queer Khmer are more freely expressing themselves.

On Instagram, dressing in drag, wearing less normative fashion, and using queer sexual innuendos are common in a way largely foreign to Khmer Facebook. Whether this will remain so as more users come both online and onto Instagram will be interesting to watch. Already many Instagrammers are using private profiles. Studying how use changes between public and private profiles would be fascinating research.

While sharing minoritarian identities is progressive, Khmer Instagram remains largely apolitical in an overt sense. While I’ve seen hundreds of videos of illegal evictions by police and information about deforestation or corruption on Khmer Facebook, I’ve seen next to nothing about this on Khmer Instagram. Perhaps this is due to Khmer Instagrammers looking at and documenting from a state of relative privilege. These photographs represent an extremely narrow and selective portrait of Cambodia today.

While lagging behind many of its neighboring countries in terms of access, infrastructure, and education, Cambodia is indeed changing quickly. These photographs represent a few of the Cambodians who are benefiting from, capturing, and sharing that change; both amongst themselves, and with the world. This may be a glimpse of the future of Cambodia for many, but with political turmoil, corruption, and lack of free speech, this version of Cambodia may exist only for a privileged few.

Free Speech

Already, Facebook posts calling for peaceful protest last year have landed several posters in jail, charged with inciting social unrest.10 The Cambodian People’s Party, the ruling party led by Hun Sen for the last 25 years, which solidified its power through a coup, has been violently resistant to critique. They control much of the radio and television, and have been pushing for further surveillance of the Internet, especially social media.11 Hun Sen has explicitly warned Cambodians that they cannot remain anonymous online, and that he can find posters in seven hours, should he want to.12

Furthermore, we must always remember that we are discussing a company: Instagram, or more accurately, Facebook, after the latter purchased Instagram in 2012 for $1 billion. Facebook is a massive foreign business, with an eye on the bottom line. After receiving much bad press for breaking net neutrality and zero-rating, Facebook rebranded Internet.org to Free Basics, as a humanitarian venture seeking to connect the rest of the world to the Internet, albeit a stripped down, walled-garden version. Free Basics, which finally came to Cambodia in the middle of this year, seeks first and foremost to get people onto Facebook. Positive social impacts are advertised, and real, yet the financial realities must always be considered. Free Basics offers just that—free basic services that use zero data from your plan. In general Free Basics includes a few social service websites and government websites, and of course, Facebook, albeit with no images. How can creative posts on a private company’s platform become a powerful affront to the dominant narratives inflicted on Khmer, both from local politicians and outside international media? How can Khmer Instagram become more political, a citizens’ media?

#BlackLivesMatter offers clues. What began as a Facebook post, turned into a hashtag, and then into a keyword used by protests around the country; #BlackLivesMatter has grown into a national debate. This is about leveraging media affordances to give a platform of those so often ignored in national or international conversations. Later, watching as the presidential debates fielded questions on #BlackLivesMatter stands testament to the power of this tactic. Of course, whether this leads to real legal and systemic changes remains to be seen.

What Rodriguez and #BlackLivesMatters teach us is that, for Khmer Instagram to grow into a true citizens’ media, there need to be communities and organizations dedicated to that goal; social media won’t become citizens’ media without hard work. The intersections of location, community, and sites of production are not only vital to understanding the media produced, but are where the social and political power of that media truly rests. As of now there are very few groups, formal or informal, nourishing this kind of media in Cambodia.

While a handful of great international organizations have done work with citizens’ media in Cambodia, there are few dedicated exclusively to Cambodia. The Cambodian Center for Independent Media, Geeks in Cambodia, and the Open Institute seek to develop and promote new technologies and tactics for the empowerment and betterment of Cambodian society. Arts organizations like Sammaki, Sa Sa Art Projects, and Cambodia Living Arts are dedicated to empowering local voices through the arts. While as of yet there are no Khmer Instagram meet-ups, Male and Sothea are just beginning to plan the first to take place sometime this spring.

Given Cambodia’s poverty and low Internet penetration, looking for more followers or an audience that the Instagrammers could leverage into financial gain means looking beyond their own borders. Accordingly, posts are often excessively hashtagged and almost always in English. Furthermore, the posts are rarely country-specific, focusing instead on international hashtags, reaching for greater recognition. For a citizens’ media to emerge from Instagram, this tendency of looking outward, beyond local media and the people who create it, would have to change.

These mobile photographers are a creative elite, a small forefront of Cambodia, and without a larger local user base or industry that can support them through creative industries or even art exhibitions, it is likely they will continue to look outwards, rather than in. Without the help of legal protection for more free speech, and more nourishment of local organizations to leverage this kind of media, citizens will continue trying to skip passed the hard work of building local communities, reaching instead for scholarships, grants, and awards to leave . . . lottery tickets that don’t make for much real change for Cambodia.