Red Horse: Drawings of the Battle of the Little Bighorn

Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University

328 Lomita Dr, Stanford, CA 94305

January 16–May 9, 2016

It would be hard to imagine a show of contemporary art that would be more resonant than the exhibition of the historical drawings of Red Horse, a Minneconjou Lakota, of the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Red Horse twice gave testimony—in sign language—on the Battle. As part of the second testimony in 1881, he produced 42 drawings, 12 of which are currently being given a rare public showing at the Cantor Center for the Arts at Stanford University. There exists a large body of testimonies from both sides, as well as archeological reconstructions of the Battle, and the historical interest of these drawings is considerable. Where the drawings present an extraordinary stimulus for and challenge to vision and response is in their expressive embodiment of demands that are still active in shaping the contemporary arts: the necessity of re-invigorating a tradition in the face of its obsolescence; the requirement of addressing the interests of multiple audiences with different sets and levels of cognitive stock relating to the topic; the interest in working out new models of achievement in a cultural climate of diffuse and easy relativism, one that presents a face of indifference or even hostility to the stringencies of artistic expression; the requirement of giving an individual’s perspective on collective experiences while resisting the pressures towards a hyper-individualist self-presentation that sets the individual artist over against the collective she aims to represent. The pressure of a thousand cultural atmospheres weighs upon these works.

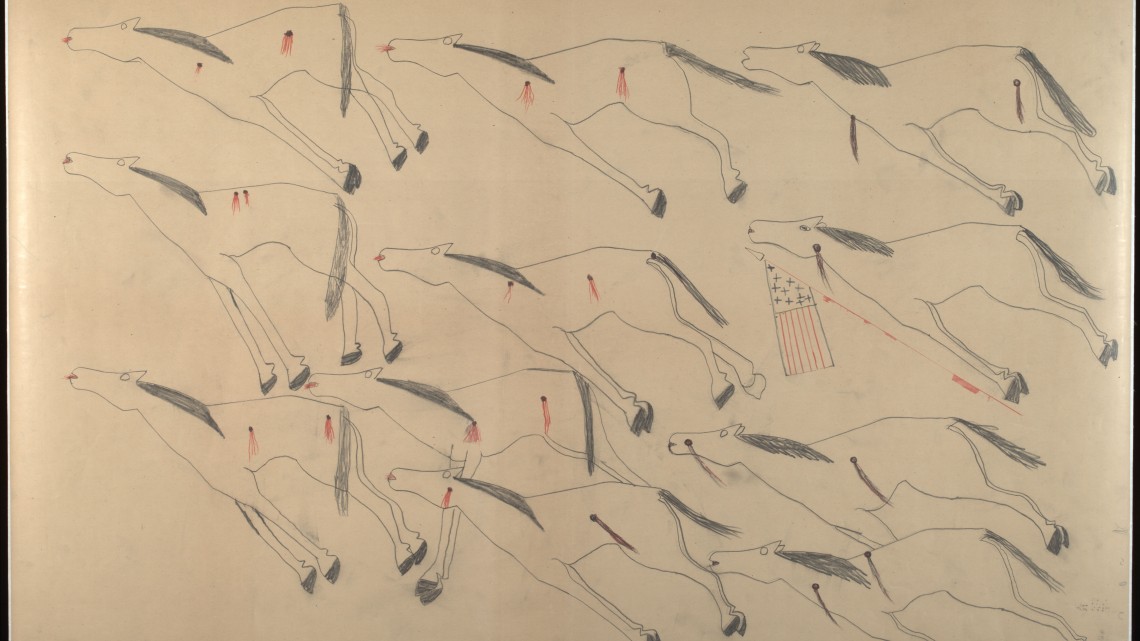

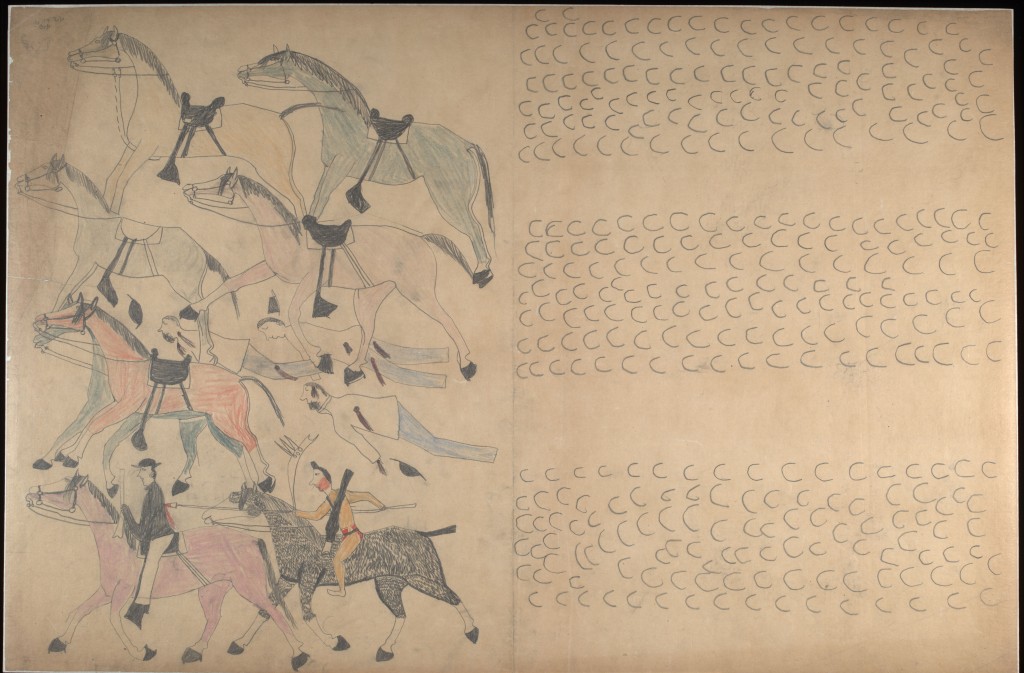

Red Horse (Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, 1822-1907), Untitled from the Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1881. Graphite, colored pencil, and ink. NAA MS 2367A_08568600. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

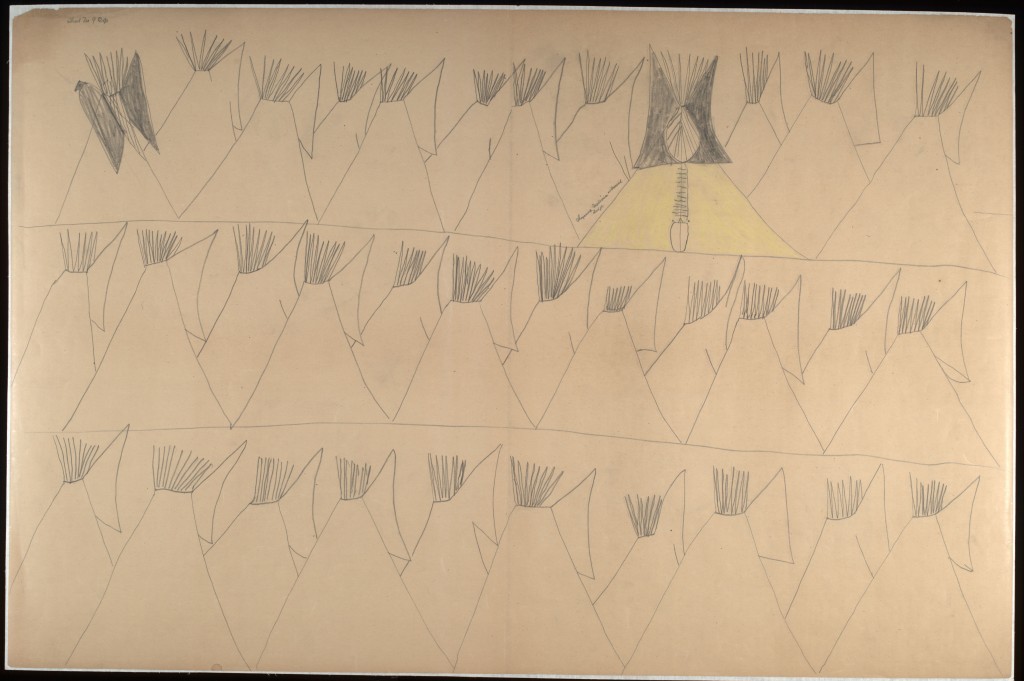

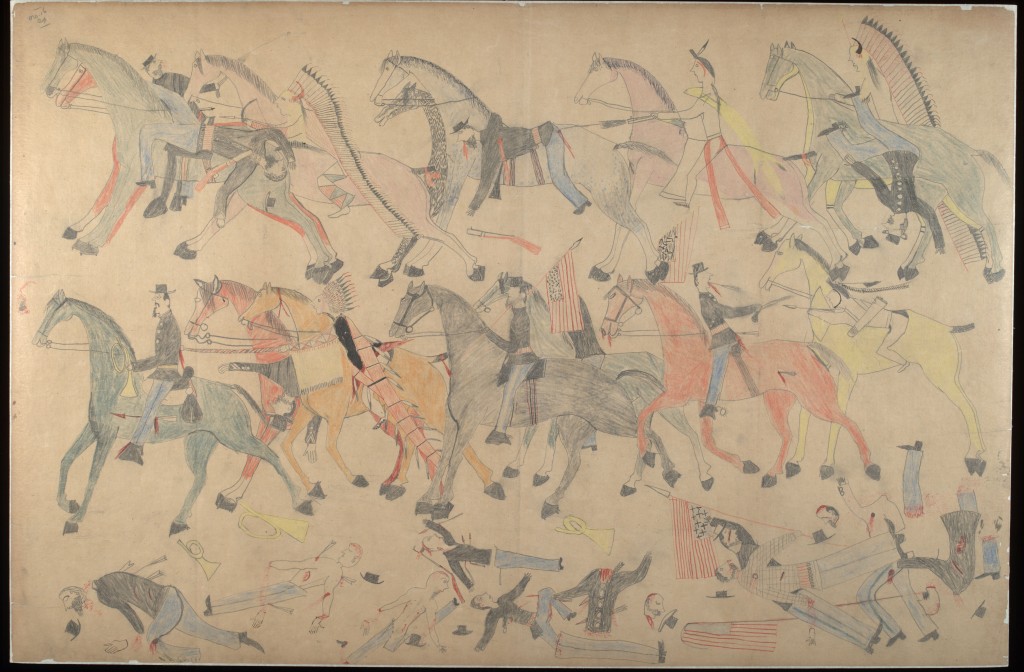

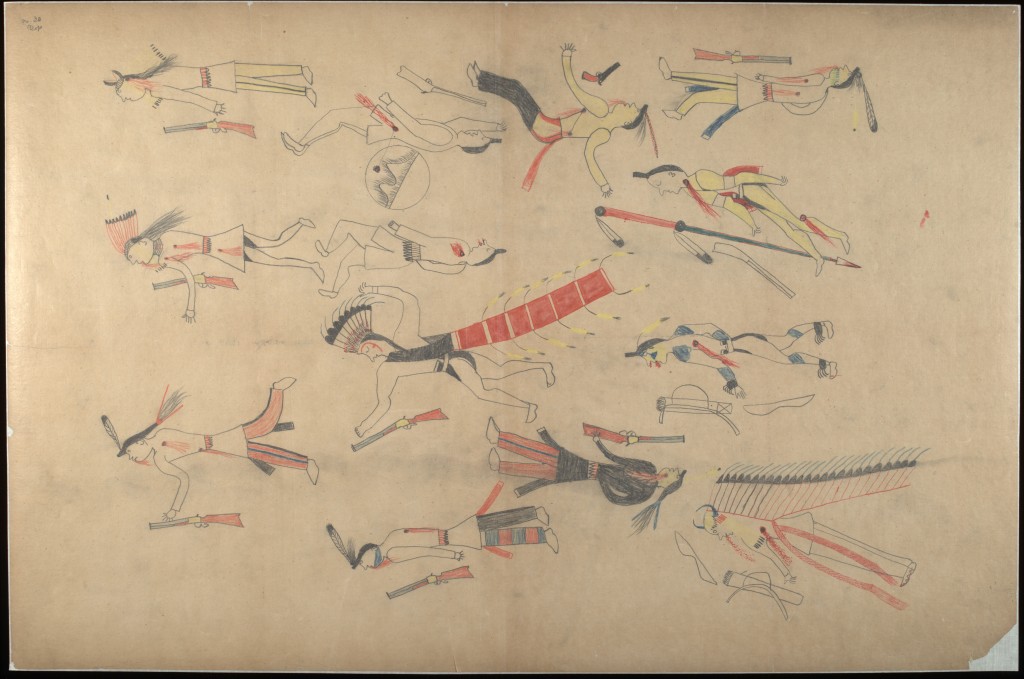

The drawings are instances of so-called Ledger art, a short-lived genre of works produced by Plains warriors who used paper and drawing implements supplied by or taken from whites. The characteristic subject matters of Ledger Art are the prestigious exploits of the warrior-artist, particularly ‘counting coups’ (touching an adversary in battle), killing an enemy, stealing a horse, or, less frequently, receiving a vision. Most scenes in Ledger art show only a single such incident, though occasionally artists will build up more complex scenes out of multiple instances of one-on-one interaction. Red Horse, faced with the challenge of recounting the battle, shows anywhere from 10 to several dozen figures in each drawing. Only three of the 12 drawings show battle scenes, while fully half depict the aftermath of slain soldiers and, in one drawing, warriors, as well as the return of the warriors to camp with captured horses. The first three drawings set the stage, with two similar pieces each showing 10 mounted soldiers, and a third depicting a mass of outline drawings of teepees in three registers; one tepee is highlighted with yellow and drawn in a slightly more detailed manner than the rest, perhaps indicating that this is Red Horse’s own dwelling. In two of the battle drawings the sense of collective density and confusion of incident is reinforced by Red Horse’s giving over fully half of the drawings, their right sides, to c-shaped hoof markings, indicating the large number of horses involved. The aftermath drawings show many dismembered or beheaded soldiers, a sign that the women have already done their work of trophy-taking and symbolic humiliation of the defeated.

Red Horse (Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, 1822-1907), Untitled from the Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1881. Graphite, colored pencil, and ink. NAA MS 2367A_08569200. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

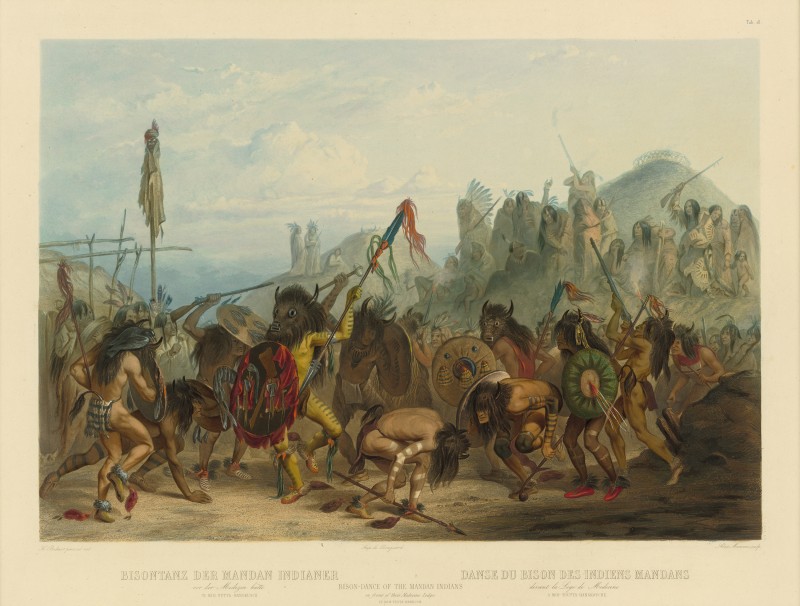

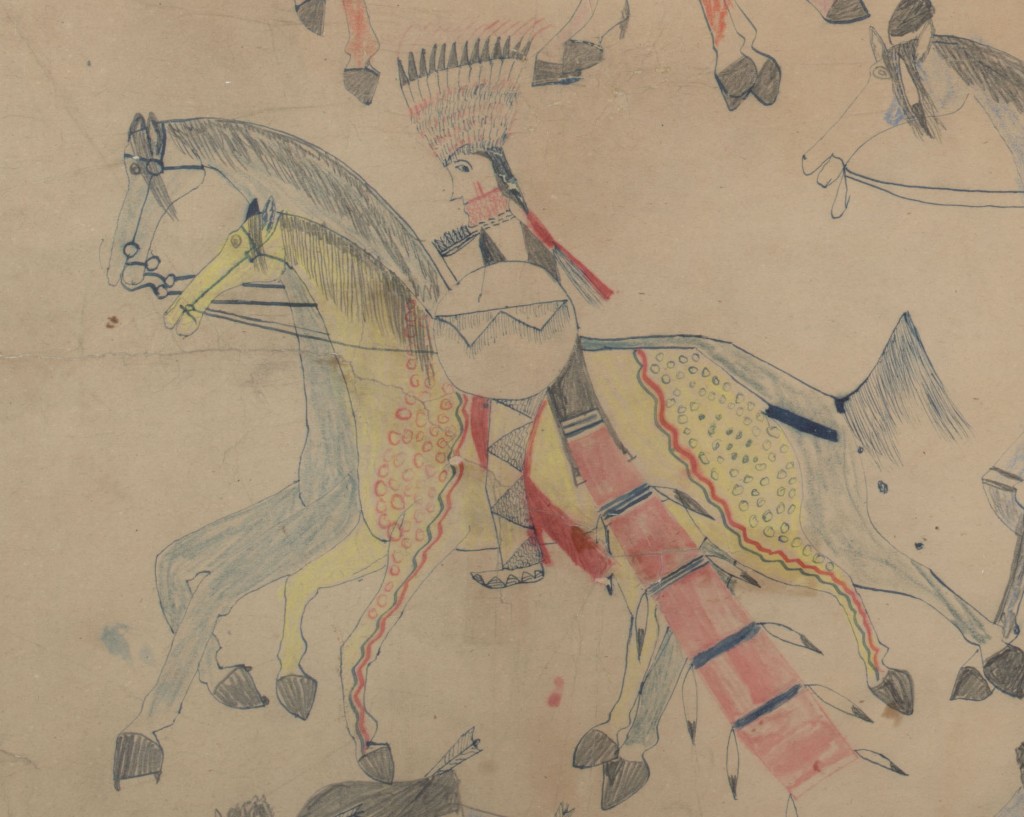

These drawings, and Ledger art generally, are nested within a broader tradition of warriors’ Biographical art, always concerned to depict their exploits.[1] The Biographical tradition seems to emerge from an earlier tradition of Ceremonial rock art that depicted isolated figures, often with upraised arms expressive of trances or prayers. On the scant available evidence, the Biographical tradition flourished in the decoration of buffalo hide robes, and was attested among the Mandan people by the expedition of Prince Maximilian to the northern Plains in the 1830s. With the U.S. Army’s campaigns, the extermination of the buffalo herds, and the decimation and enforced enclosure of the peoples of the Plains, the major vehicle of the Biographical tradition became the whites’ ledgers, which exist in sufficient quantities to permit the reconstruction of a trajectory of stylistic development. A key stimulus to the stylistic change within the Biographical tradition was exposure to the whites’ techniques of naturalistic rendering, keenly observed in the work of visiting artists, in particular Karl Bodmer and George Catlin in the first half of the nineteenth-century. The increasing naturalism of Ledger art takes a trajectory vaguely reminiscent of the great period of the development of naturalism in the sixth- through fourth-centuries B.C.E. in Greece: the range of postures expands, internal differentiation emerges (in Ledger art particularly in the use of textural and decorative colorings), and more markers of spatial location and recession are introduced, though quite sparingly. In contrast to the familiar, seemingly steadily paced march of increasing naturalism in Greece from the Archaic kouroi—through the merger of ideal-erotic conceptions with the dynamics of muscle and bone in the Canonical figures of sculptor Polykleitos, to the rejection of idealism by Lysippos with loosely coordinated limbs and surfaces—the Plains artists seem to hesitate with the introduction of each new kind of naturalistic detail, and explore the implications for evocations of the glory of men. So for Red Horse in 1881, the faces have outlined noses and mouths, but no effort is made to convey individual physiognomy or expression. Instead in, for example, the two drawings of 10 white cavalry, each man is given a different kind of facial hair, and in both drawings one figure is shown wholly clean-shaven. Each horse’s hooves are carefully rendered, but the boots of the soldiers are oddly schematic and seemingly pointed backwards; the interest seems to be in displaying something of a blur of dark patches, hooves and boots swaying to different muscular movements and crossing in polyrhythms.

Karl Bodmer, Bison Dance of the Mandans, circa 1840s. Hand-colored aquatint. Courtesy the Internet.

The drawings are exhibited in a kind of institutional mist of pious pedagogy that is not wholly unexpected, given its setting within the metaphorical shadow of Stanford’s Hoover Tower and the Hoover Institution, a long-time quasi-academic bastion of political conservatism. The viewer is continuously subjected to a self-congratulatory video that urges one to think that the presentation of these drawings is a courageous, even avant-garde action in offering a non-canonical perspective on the Battle. Such a curatorial frame might have been appropriate 50 years ago, but is senseless over 40 years after the publication of Dee Brown’s widely read Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee.[2] The slightly more substantive curatorial point is to stress the multiplicity of approaches that the drawings elicit: photographs of a few of the drawings are accompanied by commentaries from a military historian, a museum professional, and an art historian, presumably thereby exemplifying the video’s claim that the exhibition induces a ‘contested’ space wherein different perspectives are also somehow ‘affirmed’. One might have hoped that showing these depictions of this slaughter, itself set within a larger genocidal campaign, would not have elicited without qualification such bland liberal sermonizing.

Red Horse (Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, 1822-1907), Untitled from the Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1881. Graphite, colored pencil, and ink. NAA MS 2367A_08569000. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

This curatorial gaffe hardly diminishes the power of these works, and instead suggests a move towards more challenging questions: What can these drawings mean to us? And who are ‘we’? As noted above, Red Horse could draw from the resources of the Biographical tradition a method of depicting crowded scenes through multiplication and juxtaposition of dual encounters. Likewise, the movements of mounted fighters to and from the Battle could be depicted through multiplication of individual figures laterally, and the straightforward use of occlusion could give a rough ordering of the mounted figures in spatial depth. The Cheyenne artist Howling Wolf had already deployed such techniques to great effect in the mid-1870s in his drawings made while imprisoned at Fort Marion. More troubling to ‘our’ understanding is drawing #9, showing an array of dead Plains warriors, each bearing the signs of individual identity through hairstyle, clothing, and individualized markers of achievement, such as a lengthy war bonnet. Ledger art and the Biographical tradition generally are averse to the depiction of defeated members of the artist’s own group. What induced Red Horse to depict this? Surely not simply a concern for accuracy: this is a highly selective art, wherein the range of types of scenes is quite limited and every element within a scene is chosen and rendered for its mnemonic role, its effectiveness as a prop illustrating or sustaining an oral account.[3] Was drawing #9 a kind of tourist art aiming to reassure the white viewer that the dashing General Custer had taken quite a few Indians with him?

Red Horse (Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, 1822-1907), Untitled from the Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, 1881. Graphite, colored pencil, and ink. NAA MS 2367A_08570200. National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

One way of attempting to grasp Red Horse’s aim here is through an analogy with an analysis given by the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre of the kind of cognitive opacity that arises when attempting to translate from one linguistic tradition to a very different one. MacIntyre notes that “[e]very tradition is embodied in some particular set of utterances and actions and thereby in all the particularities of specific language and culture.”[4] He goes on to consider at length two cases where a place-name, highly particularized with regard to a set of culture understandings (as in something like: this place is X, where long ago such-and-such happened 500 years ago), is translated into different languages. One case involves translation into a language with an already extant different name for the place (this place is Y, where this-and-that happened 200 years ago). A second case is where the translation is into what MacIntyre calls an internationalized language such as modern English, where place names do not typically carry with them such a rich set of historical understands and a shared sense of how place names are produced as in the more local, pre-modern languages of the first case. Two points MacIntyre makes in the course of his account provide some orientation to Red Horse’s drawing. First, naming is always naming-for, not simply naming-as; alternatively put, things are named as part of and in the service of the increased intelligibility of some broader cultural schemes and forms of life. Second, the translation of a name, if successful, involves “that part of the ability of every language-user which is poetic.”[5] But it is not that sheer translation is poetic—anyone can simply maintain the original term in its new linguistic context, or replace the original term with a newly coined one. What must rather be re-created in the new context is something of the sense of uses and connotations of the original term. This is poetry. By analogy, one might think that Red Horse’s aim in depicting the dead warriors is not to document nor to flatter someone’s narcissism, but rather to induce the transformation of the white viewer into someone who can grasp the conventions of Ledger art, and so with it begin to gain an understanding of the life from which that art flows, and in the context of which it makes sense. What it would mean to understand these drawings fully, I cannot imagine, but if one were to extend MacIntyre’s points into this context, the difficulty of understanding these works arises because their appropriate viewer did not, and perhaps does not yet, exist. That is, the drawings register the encounter of the two cultural imaginations: the Heroic imaginary of the Plains warrior embodied in the Biographical tradition, oriented towards remembering and enhancing individual glory; and the Bureaucratic imaginary of Empire, oriented towards producing a stable and comprehensive view for the purpose of assigning responsibility. Unless and until an artistic style exists that can incorporate both aims and can receive these drawings as a precursor, their opacity is ineliminable. Whether the creation of such a style is a conceptual impossibility, or merely an historical task of great difficulty, remains to be seen.

Red Horse (Minneconjou Lakota Sioux, 1822-1907), Untitled from the Red Horse Pictographic Account of the Battle of the Little Bighorn (detail), 1881. Graphite, colored pencil, and ink. NAA MS 2367A, 08570700 National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

—

[1] For accounts of the history and development of Ledger art, see Janet Berlo’s Plains Indian Drawings 1865-1935: Pages of a Visual History (1996) and James D. Keyser and Michael A. Klassen’s Plains Indian Rock Art (2001). The finest stylistic description of Ledger art, specifically with regard to the work of the Cheyenne, is given in Candace Greene’s Structure and Meaning in Cheyenne Ledger Art (1996).

[2] Brown, Dee. 1970. Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee. New York: Bantam Books

[3] For a recent discussion, see Carlo Severi’s The Chimera Principle (2015). Severi treats the style of Ledger drawings as an instance of the global phenomenon of ‘primitive drawing’ as famously characterized by Emanuel Löwy in The Rendering of Nature in Early Greek Art (1907). Primitive drawing is shaped by its aim of evoking memories, and is characterized by the salience of outline, homogenous coloring, highly restricted range of typical graphic schemas, and little or no interest in location of figures. Generally in such drawing, detail is introduced very sparingly in the service of its mnemonic role with a range of possibilities: this kind of beard, not that kind.

[4] MacIntyre, Alasdair. 1988. Whose Justice? Which Rationality? Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, p. 371.

[5] Ibid, p.382