Since meeting poolside in San Diego in 2009, working on our tans in lieu of attending yet another ‘Accepted Students’ event at the University of California, San Diego, Sadie and I have been in sync. Initially drawn to one another by shared interests/approaches to life, we quickly realized that there was much more to connect us: both only-ish children, 1984 babies, mixed girls, self-evidently fly would-be sophisticates brought up in urban spaces (though to my forever regret, on opposite coasts), and creatively-inclined. From that first meeting, through graduate school, cross country moves, new cities, and new concerns, we have forged ahead in this thing they call ‘the art world,’ pooling our shared knowledge and expertise in the hopes that this collaborative and love-driven model will allow us to remain true to our work, ourselves, and to the times, places, and people we come from. It makes perfect sense—an artist and a curator—but it is the greatest privilege for both of us to grow together over time, as friends, peers, and co-conspirators. We have had many, many conversations—some of them profound, some of them silly, some of them life-changing, some of them fire-starting. Thus, what follows is really an excerpt or snippet from a much longer and larger conversation, one that we are always having, and always will be.

You’ve talked before about your work as a way of seeing things, and not a way of making things necessarily, which I think is a really important distinction and idea. You work in all these different registers, but there is always an overall connecting vibe or sensibility.

I think a lot of artists have a ritualistic relationship to their materials. People talk about the paint itself informing their choices and how a lot of ideas come to them through the hours spent in the studio . . . but for me it is more about looking at the world and noticing things as they occur and actually just copying them and editing and putting things together. That’s why I use a lot of found text and found objects. It ends up taking many different formats but there is something running through that you can identify as me, my authorship, my perspective.

Can you explain what that perspective is?

Well, I guess it involves my interest in minimalism and conceptualism informing the way I look at my family, our history, the personal as political, West Coast culture etc. . . . My work is very concerned with “the everyday” but is also tethered to the other-worldly or the abstract, or the poetic, and I hope it gives us the space to dream and imagine things being different. Headspace as outer space is a concept I keep coming back to. I’m documenting our lives but also hinting at an escape, a science fiction maybe, and bigger possibilities. I argue that we need abstraction and magic and glitter—that people need poetry.

I wanted to ask you about bookmaking. We went to graduate school together at UC San Diego starting in 2009, and were very fortunate to be there together, and I’m very lucky in that I’ve been able to watch you grow as an artist and learn and do new things and then see how old things come back and are reconstituted. One of the things that you really learned at UCSD was bookmaking, and I definitely think of it as an important and ongoing part of your practice. Can you talk a little bit about that process and how it happened, but also how it’s generative now? What was the first book that you made? And where can we see these books?

Well, meeting you was definitely the most important thing about grad school, but getting into bookmaking was also a big development for my work. The first book I made was called Plus One, and it was produced by my friends at Gravity and Trajectory (GR//TR), a publisher in San Diego.1 They wanted to work with artists who hadn’t yet worked in the book format and the idea was for the artist to approach the book like a gallery wall. They had a very strict format/structure for the book and this helped unify all the different elements that I was interested in but never thought would make sense to hang on a gallery wall. All of sudden I got to insert all of my crazy interests from Mexican nail design magazines, to street shots of Oakland, to Lindsay Lohan, to my puppy that I lost in a custody battle—all of these things exist in the same plane in my mind, and the book allowed that to exist outside of my mind and still feel cohesive. So, making that book gave me the freedom of inclusion. The book format acts as an equalizer for disparate types of images that are sourced from different places—reference material or ephemera or little objects that I collected—because once everything is on the same size page and bound together it allows the reader to consider them all collectively, like a remix in a way. That first book is long sold out but some of my newer ‘zines are available on my website, like How To and How To Vol 2.2

I remember when you were making Plus One, and it was complicated to do it, but that book has one whole page that is just your Sadie Barnette™ shiny sparkle holographic vinyl paper. It’s so interesting to see it presented that way because that paper, that image or that pattern, appears throughout your work, whether in a book, drawing, photograph, etc. You use it in a lot of different ways. It’s not the easiest material in the world to use in a book, but it nods to all the different scales and spaces that you’ve used it. Can you talk a little bit about that trademark paper and how you feel about it? Why you are so in love with it?

The element of glitter appears in my work in many forms, sometimes actual piles of loose glitter as part of a sculpture, or little rhinestones in drawings, or yes that hologram material that I love. I created a whole wall out of it for my thesis show and then did a deconstructed version of that in 20 plus individual frames at a solo show at Ever Gold Gallery in 2013. My fascination with glitter has to do with transcendence or ecstasy, escape—it’s mesmerizing, it’s hypnotizing, we are all drawn to it and it can transport you somewhere. But I also like how fake and cheap it is. It’s a performance, not the real thing, like rhinestones vs. diamonds. With the holographic vinyl paper, there’s one angle you can look at it and it is just completely shiny and supports the illusion of it being more than paper. It works, and then there’s another angle where you look at it where it’s pretty, but it’s just paper. It’s about illusion and I like when it fails just as much as when it works.

![Installation view, Composed and Performed at Ever Gold Gallery, San Francisco, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Ever Gold [Projects] (formerly Ever Gold Gallery).](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/sadie2-1024x768.jpg)

Installation view, Composed and Performed at Ever Gold Gallery, San Francisco, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and Ever Gold [Projects] (formerly Ever Gold Gallery).

Can you talk about photography in your work? You make all sorts of things—drawings, books, photographs, objects, sculptures, installations, murals, etc.—but a lot of it is rooted in the photograph. Were you a photographer first?

I was originally studying photography as an undergrad at CalArts but then I got interested in some of the broader conversations happening in other art departments. I started experimenting with found objects and drawing and other mediums, and never really looked back, and now one of the exciting things about working in so many mediums is that the choice of the medium is itself an element of the work. If I’m using one medium it’s because I think that that’s the right medium for that idea at that time and context. But photography is definitely what got me—not what got me into looking, but what helped me focus my act of looking into an act of making. So I’m always, always shooting photographs, collecting them and then looking back over thousands of pictures to select what will become a mural, or a framed print, or needs to be cut up and collaged or should appear in a zine. The zine is one place where certain types of photographs that I would be hesitant to put on a gallery wall find their homes. Some of the more personal or emotive or intimate or . . .

Sexy? There are some sexy pictures.

Ha! Yeah, images that are sexy, or even that have a certain subcultural affiliation or “otherness,” can be so easy to consume or commodify when they exist as objects on a gallery wall. I am protective of these images. But these same images in a book format feel more like passing a note or letting someone in on a moment, as if you’re speaking to one person at a time. Looking at art on a wall can be more of a collective experience, whereas looking at a book is usually a more personal experience.

When I think about your work, I think about specificity. You’ve talked about specificity as universal—specifics as the universal experiences of things—as opposed to exceptional, which is what happens particularly in relation to “marginal” stories and situations. That is, these stories are somehow perceived as exceptional or different, which assumes that there is some other “real” universal out there. I often feel that you’re making a claim for your experience—your life, your family, how you spend your time, what you’re interested in—as universal. In keeping with that, location and geography both seem important to you, particularly California. It’s the place you are speaking from. But then again, you just finished a residency at The Studio Museum in Harlem in New York, which is another very iconic location. Can you tell me about that year and what being in Harlem was like for your work and your process?

The residency was amazing, and Harlem is amazing and inspiring. I don’t think it necessarily changed my work so much as it was just an affirmation of why it matters to make work and what the dialogue around producing culture can be. It did help to get some distance from California. It helped me to isolate what the elements are in my work that are particular to California, so sharing that landscape with a New York viewer and seeing it through their eyes, helped me to realize California architecture is very particular and some of my images announce themselves as being very California.

Speaking of Harlem, in the interview you did with the other two artists-in-residence (Lauren Halsey and Eric Mack) in the brochure for your exhibition Everything Everyday, you said “I always think every black child in America should go to Harlem for a week.”3 It’s such a beautiful idea. I love imagining such a trip—shout-out to any person or foundation out there that wants to give us money to make it happen! What is so special about Harlem?

I wish we could have that as a rite of passage tradition! As African Americans we are sort of homeless in terms of the idea of a homeland. But Harlem just feels like a homecoming. You can feel the history and spirit in Harlem. People worry that Harlem is changing and it’s true that there is a lot of gentrification going on, but Harlem is still the most Harlem of anywhere. Obviously there are amazing communities of black people being brilliant and making art and being fabulous all over the country, but in Harlem it is taking place on a very public stage, has a public square kind of feeling about it, and creativity is on display and people are presenting themselves in very active and considered ways. There are church ladies and punk rock gay kids and dudes on hoverboards and all these different, sometimes contradictory, ways of expressing blackness, but it’s all happening at the same time on the same corner.

Installation view, Everything, Everyday: Artists in Residence 2014–15 at the Studio Museum in Harlem, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and the Studio Museum in Harlem. Installation view, Superfecta at Charlie James Gallery, Los Angeles, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

One of the other things about Harlem that is amazing is that it is, as you said, this kind of homeland on both literal and poetic or metaphorical levels, but it’s also a space of contemporary migration. There are a huge amount of African immigrants who come to Harlem now. That replenishing is part of what keeps Harlem from being a museum piece, keeps it vibrant and dynamic. Regardless of the changes wrought by development and gentrification, and all these things that pose a threat to it remaining an active space and a black space, it persists and changes. It’s not some perfectly preserved sepia-tinted Harlem Renaissance thing. It’s like, yeah, there are hoverboards.

So Oakland and Harlem—as you were saying, Harlem is this black mecca, but Oakland is also kind of a black mecca. Maybe not on quite the same scale as Harlem, either in size or reputation, but I think it does function that way, especially for black radicalism and activism. Can you talk a little bit about Oakland, now that you’ve been back there for a couple months after being away? You’re from there, and it’s a place that people flock to, like New York, but you’re actually from there and grew up there. Tell me about that.

Being from Oakland I have always felt that there is a wonderfully disproportionate amount of political activism and amazing music and dance and trendsetting/slang that comes out of this tiny place. Oakland is just one of those places that has a very strong identity so if you’re from Oakland that’s a big part of who you are, and when you’re living in Oakland your life is engaged with this character of Oakland. Just like people from New York, they’re in a relationship with New York itself at all times.

It’s so true. Like, “How are you and New York doing?” You’re literally in a relationship. And sometimes it’s real messy.

Just like Harlem is being gentrified, so is Oakland. The neighborhood that I grew up in gets a new fancy name and then everything is a coffee shop. I saw a statistic that rents have doubled in Oakland since 2009, and obviously no one’s wages have doubled. A lot of my friends are no longer living in Oakland because it’s just so expensive. There is some conversation and activism around the issue, but I don’t know what the answer is. Oakland has always been a very welcoming place, and there’s always been a lot of different people living side-by-side, sometimes with hilarious results, so I don’t want the issue of gentrification to force us to be territorial and say no new people can come, because that’s not what Oakland is about . . . but as Oakland becomes less and less affordable, it won’t be the Oakland we know and love.

I think it’s such a hard thing because New York, Oakland, and the Bay in general, are places that people are drawn to and attracted to by all this amazing culture and creativity and history. But it’s a double-edged sword—your very presence displaces the people who made it great and made all the culture, and then you can’t afford to live there either. It’s not even like the people who came and were attracted to it are themselves now able to stay. It’s unsustainable for almost everyone; it’s a very strange scenario.

Can you talk a little about the show you just opened in LA? Another iconic location!

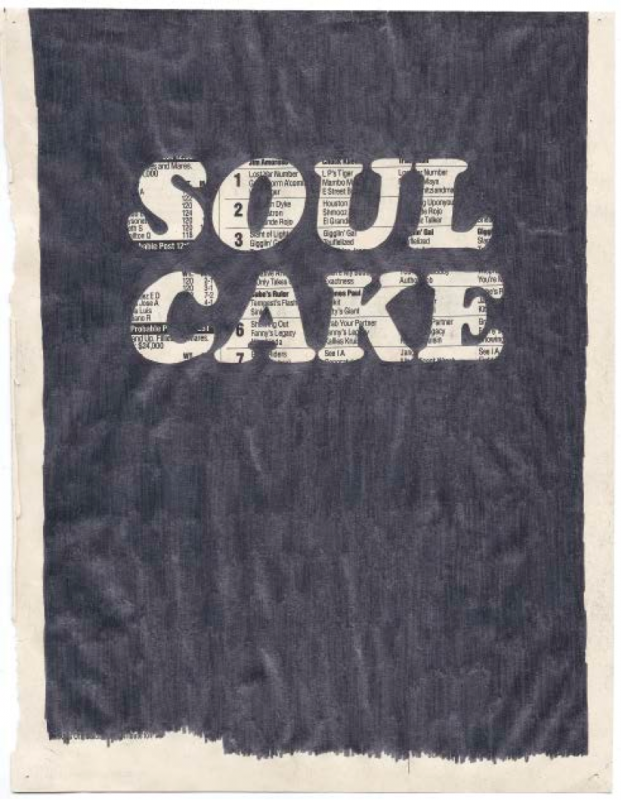

The show is at Charlie James Gallery in LA’s Chinatown and is called Superfecta—which is a type of bet that you place at the horse racetrack. I’ve always been fascinated by the racetrack. I used to go with my dad when I was little and it’s a very interesting place because there’s a melding of very specific vernacular and very serious betting and statistics and codes, but then also was this fantastical mythic element of the horses themselves and the names that they have, which can be very over the top and showy, but people are also very serious at the race track. It’s a serious business. People are trying to make rent and that kind of vibe. But as a little girl I loved the ponies and even now when I go I see other father-daughter pairs, and I think it’s a hilarious and unlikely location for father-daughter bonding. For the show, I used the names of the horses as the primary way to investigate the space/culture of the racetrack. There are these amazing poetic names and I think of them as found poetry. Names like Derby Kitten, Blondie’s Bling, Soul Cake, Pacific Pride, Hard Sun . . . they run the gamut of referencing old Hollywood, or there are war names, and princess names, and everything in between.

Untitled (Soul Cake), 2015. Graphite on found racing form, 15 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

And not necessarily names that have anything to do with the horse’s performance. They are fanciful and seem kind of arbitrary. Are they?

Sometimes the name might come from the parents. If the parents are named Endless Fancy and Hollywood Affair the kid might be called Endless Affair or something like that.

So it’s familial or genealogical, which also gives the naming practice a literal function as a way of imparting information to bettors about the horses. For people who are very serious about it and doing it for money, it means they can follow the lineage. Though they could do that by assigning numbers or something boring, like Horse Number 7 who is the daughter of Horse Number 3 and Number 4.

That would be boring and no one wants to get behind that. The horses aren’t named like people or even boats, which are normally given a humanizing name. They don’t give horses names that make them seem more like beings. They’re more like brands or slogans, which I think is interesting. I’ve always been interested in names and nomenclature, and the act of choosing what to call something. I think it says a lot about who we are or what we think about, or who we want to be or hope to be.

Untitled (Racing Form 6), 2015. Graphite on found racing form, 15 x 12 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Charlie James Gallery.

It’s interesting that you’re talking about the naming of the horses having this family tree, lineage element. In your show at the Studio Museum, you made a lot of reference to your specific family tree, more via the relationships between your relatives and you than through individuals’ names, children, marriages, etc. Maybe there’s a connection between the racetrack work and that work? In any case, the show at Charlie James, is it primarily drawing?

I did a lot of drawing for this show—I wanted the many obsessive hours of my drawing labor to match the obsessive nature of gambling. Most of the drawings are done on pages from the daily racing forms that you find at the racetrack. You can buy this booklet of information, and the pages are just covered in tiny, tiny numbers and stats. I know what some of them mean because my dad has told me, but he totally understands what all of them mean. People use these statistics to create complex equations to handicap the odds. So I drew on these newsprint sheets names of horses and also numbers using really soft pencils and almost covering entire sheets of paper with pencil marks to get a thick shiny metallic coat of graphite on this really thin delicate newsprint. I let information come through the negative space, either the statistics about the horse or some of the advertisements in the program, which could be little stacks of money, or coins, or little horses. And there’s a lightboxed photo image that was taken outside my dad’s house in Compton, showing a pony ride at a family house party. There’s a whole little-known horse culture in Compton, because there are some areas that are zoned for equestrian ownership. You can’t just have a horse in your driveway, but Compton is a place where you can have a horse. You’ll see horses walking down Compton Boulevard. South Central LA is the most car-centered place ever, but there are also horses down at the liquor store sometimes. The photograph is blurred—it’s the shot I took right before my camera focused. I chose that one because it’s not a portrait of the particular horse, or that exact party, but it’s about that phenomenon. It could be somebody else’s cousin or a different horse—it’s about the idea.

With photography, people have that desire for information, like who are these people, what are their names, where are they going. The blurring lessens that impulse. It also becomes a formal aesthetic choice, though it may have been inadvertent. It gives it such a mood, such a feeling and a vibe—that kind of hazy twilight time of day that’s really lovely. It becomes surreal-ish.

How long is the show at Charlie James going to be up?

It will be up until February 20th.

Then what are you doing in 2016?

The next thing I’m doing is an artist residency at the Hermitage Center in Florida. I’m very excited about that. I think it’s going to be another interesting experience of taking yourself out of your normal context. My work often has to do with urban dwelling experience, so what happens when I’m on the beach in Florida for a month?

All good things.

Yeah, so I’m looking forward to seeing what experiments I want to do, what I want to think about, what I want to make, what I want to look at, what I want to read. I’ll send you a postcard.

1) GR//TR was founded in 2010 by artists Christopher Kardambikis and Louis M. Schmidt.

2) www.sadiebarnette.com

3) Everything, Everyday: Artists in Residence 2014–15