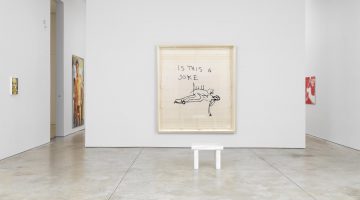

The following conversation took place at Paul Karlstrom’s San Francisco home on March 22, 2014, the day after the opening of Brooklyn–based Jemima Kirke’s first solo exhibition at Fouladi Projects, also in San Francisco. The main subject was her experience at the Rhode Island School of Design. She admits that she did not take art school seriously and now regrets that. She “made things” but did little serious painting until, a few years later in Delray Beach, Florida, she was “rescued” by a paintbrush. The following excerpts, edited for publication, tell Jemima’s story in her often-colorful words. Subsequently, she has divided her time between acting and spending hours in the studio, continuing to paint portraits of friends and family. The critical question in terms of what her future as an artist might hold is to what extent she will move to a broader range of subjects and claim them as her own, thereby separating herself from her various admired sources, notably Alice Neel. The prospect of observing that evolution is intriguing.

Today is the day after a very special one in your life as a young artist. And mine, too, because we met at your opening. I believe it was your first solo gallery show. I understand from Hope [Bryson] and Holly [Fouladi] at Fouladi Projects that you almost sold out.

Everything?

Two things left. That’s almost . . .

No, I was saying “everything” thinking that maybe those last two sold, which would surprise me.

I’m interested to know how you feel about that. Was that expected, almost selling everything opening night? This generally happens only for much more established artists.

It wasn’t expected, and I woke up this morning thoroughly depressed.

Really?

I did. I woke up at 5:00 and I couldn’t go back to sleep. And I don’t know exactly why. But I thought with any sort of great change there’s always that feeling of remorse. I just felt at that point that my obligations to myself and my work had changed. And I suddenly felt the pressure. It no longer became this exciting endeavor—this possibility of going into the studio and it may or may not work.

And escaping?

Yes, to escape. It may not work; let’s just paint and see what happens. I might not feel the pressure, but I’m anticipating that I will. And also how many of the paintings sold because of the show and [how many] because they’re really good. I have no control over that—why people like it. But you can’t help but think of the least-wanted reason—just because I’ve made a name for myself on Girls.

That sounds like a very mature response to what happened. Because it’s very unusual for new artists, for younger artists—by the way, are you 28 or 29?

28. 29 in a month, so you can say I’m 29. I feel 36. It’s the same shit, isn’t it?

Yes, well, it is. It’s just a matter of—of your youth—how young. And you’ve enjoyed—I can’t say unprecedented success, but unusual.

For me it is.

And there may be a little bit of anxiety, as you say, tied to that because of the expectations. Is that right?

Yeah. Well, when I saw them hung on the walls so beautifully and people—especially you—taking them so seriously, I was humiliated. I really was. Oh, my God, if I had known this is how professional the presentation would be, I would have done so many things differently. Or, God, now does this mean that people are watching me closely? Watching my work closely—what I obviously always wanted.

Well, it’s like you’ve been deprived of a more leisurely ascent.

Lola, 2012. Oil on canvas, 35 x 25 inches. Courtesy of Fouladi Projects.

Yes. I always said when I was depressed about my work . . . I’ll never compete and all that. My husband would remind me of my favorite artists and be like, “Go look at their biographies again and look at when they got their breaks or when their work was the best.” That was comfort to me, that it’s okay that this set of paintings is not what will be my best work. They don’t have to be. I’m not as smart as I will be in 20 years.

And not as practiced.

As experienced and practiced, yeah. There are some paintings I look back on from 10 years ago, and I’m like, wow, those are great. And I’ll never make those again because they came from a specific time and set of circumstances. Those were accidents in a way—a lot of my good paintings I find are accidents, and I hope that one day those accidents will be more frequent.

Well, I expect they will be. It’s interesting and becoming, this modesty.

It’s not modesty, though. It’s insecurity.

But one thing that you’ll run up against—and I just want to talk a bit about what I dealt with straight on in the essay [in the gallery brochure]—is the celebrity factor. You are a celebrity, thanks to your buddy Lena Dunham.

Yeah.

And to Girls. In my essay I wrote: “Thanks to the popularity of Girls, Jemima is far better known than most of her contemporaries making art. It’s extremely difficult for anybody to establish a reputation in the art world. In visibility, at least, Kirke has a foot up.”

Yes, I do. I agree. But a couple years ago, in 2010, when Lena and I went into this show together, I was terrified and very defensive about anyone approaching me about my paintings.

You mean you tried to hide that?

Yeah. Or I was skeptical, I wanted it to be completely separate, which was delusional. Someone said to me when I started the show, “If you take yourself seriously, other people will.” So I interpreted that to mean if I take my work seriously, then other people are going to see that I’m not the actor who paints. I thought I would be written off as [only] that, and I was terrified.

The art world can be cruel and snobbish.

And it’s worse now with the Internet. Now they have a platform.

Well, also art school and careerism.

Oh, yeah. I was a little shit in art school. I really was.

So your problems weren’t art school’s doing?

No. God, if I went to RISD [Rhode Island School of Design] right now, I would tear that place apart. It would be amazing, it would be so great. I would actually listen.

So you were spoiled, entitled? And now you’ve changed.

Yeah. I mean, it came with my age, but it also came with . . . I didn’t take it seriously. Or I took myself too seriously. I was sort of impressed with everything I made. Or maybe I wasn’t and that was just a cover-up. I got thrown out twice for . . .

Not doing your assignments?

I didn’t go to fucking class, you know, so how could I be taken seriously? When we had “crits,” no one ever said how awful some of the work was. So I always took that as my job. I was just grandiose, I was entitled. I would always become this—I took on a character.

That’s the beginning of your acting career.

Maybe! But I think I’d been doing it longer than that, before that. But yeah, I took on a character like some sort of flamboyant, over-the-top, you know . . .

Like Jessa [Johansson, her character in Girls]?

Yeah, like Jessa. Except back then I imagined myself as an old, gay artist—like a writer, Truman Capote—you know, someone who could say these things and get away with it. Because they were so crazy that no one would question them.

What do you feel that you missed at RISD? In other words, you recognized it was there, but you chose for whatever reason not . . .

I think it was the work ethic. Art school is such a luxurious time because all you have to do, you only have to do your assignments and be in the studio. You don’t have children, you don’t have bills to pay—well, some people do. I don’t want to sound insensitive. I didn’t take the opportunities to meet with the teachers and take their advice seriously. I guess I was a narcissist.

From your experience and then from your own thinking about art school, what would you say is the actual value of going there? One view has it that you just do your work, so why waste time going to school? What do you feel was valuable there that other people were taking advantage of? It must have to do with the teachers . . .

Yes, it’s the teachers. And for the students, it’s the isolation, I think, of being in a place where your sole purpose is to make stuff and that’s it. I mean, when you get out into your life, a large percent of your time is doing other things that you have to get done and you try and find windows of time to work, to paint—whatever it is you do.

Alma Nude, 2014. Oil on canvas, 29 x 22 inches. Courtesy of Fouladi Projects.

Right.

But I also think it’s the other students. You’re in a room with these sectioned-off little cubicles that they call studios with 20 other kids, working around the clock. And everyone’s making shit, and sometimes we make good stuff.

But it’s so exciting.

It’s so exciting and you are not yet—you don’t have to call yourself an artist yet. Like, you don’t have the pressure of that being your career, your vocation. It’s just something you’re studying.

Didn’t you have somebody among the professors with whom you made a connection?

Yeah, I loved him so much.

You had a crush?

No, I did not have a crush on him. I wanted to be him. His name was Alfred De Credico. I was his TA [teacher’s assistant] for three years in a row. I think he was a little bit Charles Manson-y in that way. Like, he could collect these admirers. People really, really did fall for him. People followed him because he was one of those people who had such strong opinions . . . who expressed with such conviction and passion. There were some things he taught me and other things he encouraged in me that no other teachers did. But for a long time I couldn’t paint without him in my head. So I was a little trapped by him.

So you were a TA and yet you weren’t going to your classes or anything. How . . .

I sometimes didn’t go to his classes to be the TA. He fired me one time. Fired me, but I was still his friend.

You were a good student in that De Credico world?

For him. I was one of his students, and he had a few of—I don’t know—these followers. It was like the Manson cult. The first year I took his class he hated everything I made. He was a drawing teacher, and he would call out my drawings as examples of what not to do. Even at the end, he used to take people’s drawings. His son was there every day. I don’t know why he needed a TA.

He wanted followers.

He did, yeah. He was a total narcissist. He had a laser pointer, and he would point to something and then his son would go up and take them and keep them. But mine he would take because he said they were so bad he had to use them as examples for future classes. My very last year at RISD I brought him a huge suitcase of drawings and I just dumped them on his desk. He stopped the class. It was the most gratifying experience when he said, “You have really gotten good.” And I loved it. He’s like, “No, some of these drawings, I want some of these drawings.” I said, “Well, you can’t have them. Because now that you’ve said they’re good, I want them.”

My husband bought me a painting of his for my birthday last year after he died. It was pretty cool. [But] I had to kill him—in my head at least—because I couldn’t work without him. So I know it sounds like I was a kook, and I was, but essentially I really started taking art—and myself—seriously years later.

So, what did you get from Al?

He explained to me, and I finally understood, that art is bigger than me. And what I make is bigger than myself, that I’m not the controller of what I make. I am not dictating this process, we’re working together. It’s more of a happening, something happens . . .

It’s collaboration.

It’s a collaboration basically between me and the . . . the stuff, the marks I’m putting on paper. He also said—and this is not novel now, but it was for me at the time—at the first class he picked up a cell phone and he put it on the table, and he said, “This is a cell phone and I can see what this looks like, and I know exactly what a cell phone looks like; I don’t need you to show me exactly what a cell phone looks like.” And kids in art school need to know that. But I didn’t realize how to get away from that [technique]. I’m very good at rendering something exactly. I know anatomy. But he was saying, “If I wanted to see this, I’d take a picture of it—show me something else.”

That’s well said and true. And this brings us right up to the modernist expressive stylization and simplification—seen in your work—that for many years contributed to a fierce, conservative resistance to abstraction.

Right.

You got your BFA in 2008. So you’re out of art school. What happened? How did you become a responsible, productive artist coming from the space where you were? And I can’t resist this—maybe the rebellion and misbehavior at RISD is the very experience that helped create Jessa, your character on Girls.

Yes. Well, Lena took a lot of my experience for Girls.

That’s what I wanted to know because I think—and I don’t want to get us off track—but I do think that, as much as I tried to avoid references to Girls and tried to say, okay, that’s a thing that she does—there has to be something to your relationship . . .

Yes, there has to be because I’m not an actor. I went into this with no training whatsoever, and every day it’s scary for me because I really didn’t know what I was doing. Lena had to write me as me. She had to write something I could do. I’m a performer. I know how to put on a show, and I used to do it very often, so Lena knew I could do it. She’s like, “If I give you someone who’s easily accessible, a character that’s easily accessible I know you can pull off these lines.” And that’s what I did.

You described yourself to me as “directionless” at the time. How did you get back on—or just on—course as a committed artist, the real thing?

Well after various misadventures I ended up living in Florida for a year. I worked in an art supply shop in Delray Beach. And this man used to come in and buy his paints. I found him a little bit creepy because the first time he met me he said that I could come and paint in his studio. And right away I was like, you know, my radar. I’m not going to paint in your studio, I don’t know you. But then by the third time he came in and asked, I was desperate. I was desperate to work, to make something. And that was the moment where I knew that was something that I needed or I would die.

Elaine On Bed, 2014. Oil on canvas, 40 x 36 inches. Courtesy of Fouladi Projects.

That’s who you were—or are.

So I gave it a shot and I went to his studio. Turns out this Jeff Whyman was a fucking angel. He literally gave me a wall with a piece of sheetrock, gave me his old paint and a bunch of old canvases—rolled-up canvas that he said I could cut up and paint over—and he left me alone. He left me alone.

Why did you choose to paint representationally?

Because I felt like I didn’t have anything else. I was desperate. I was so used to my little cozy nook that I had made for myself in my studio in school, which was where I had my collection—I collected junk, you know, all kinds of magazines and paper but also mixed materials. I didn’t have any of that stuff. I was in this nice studio in Delray, and so I just had to start from there. And it also, I think, took the pressure off to paint because I really didn’t know—I thought I didn’t know how to do it really.

But you didn’t have any preconceived notions of what art had to be, even for you? It was just . . .

I think I did, but maybe. . . . Listen, I’ve done a lot. I was in art school and I am a good—I can draw. I did study the skeleton and I studied the muscles. But I hadn’t done it in so long that the pressure was off; I’d forgotten everything. But it started to come back.

And so did you start getting better?

Yeah, I did, I got better. So then my sister Lola came to visit me and . . . I painted her.

Rather quickly, we’re bringing you to the point where you’re beginning to create what we saw in the gallery last night.

Well, I do love portraiture, but I do feel like there’s more for me to paint. There are still lifes and landscapes.

Haven’t you done some already?

Yeah.

And even done some portraits of men.

Yes, occasionally. I would rather paint younger boys . . .

They’re sort of like girls anyway.

Exactly, they really are. And so I’ve painted younger boys—but I would like to paint other things. I really am going to paint things other than portraiture. But how could you want to paint anything other than portraits? I do love portraiture.

Because you’re doing individual people. But somehow you came to the point where—and I wish we could carry this on, we can’t this evening—you recognize a worthy subject.

Yeah.

And then the art moved beyond being all about you. I think I see that as part of your progression.

I think that was demonstrated by bringing in another person. You know, it used to be me sitting at 3:00 in the morning cross-legged on the floor in some delirium, like, pasting things together. It was almost like dreaming. Whereas with another person there’s someone else who’s involved in this creative process. There’s actual life in it. Yes, bringing in the other person—as a subject to paint. It’s interesting because the process used to be for me so narcissistic.

There almost always has to be another person involved to remind me that to be worthwhile my art must be about something other than myself. This is something that I didn’t really appreciate until well after RISD.