Arnold Newman: Masterclass

The Contemporary Jewish Museum

736 Mission Street, San Francisco, CA 94103

23 October 2014 – 01 February 1 2015

Arnold Newman gathered a global intellectual utopia in his work, gaining unlimited access to the great minds of his day through his successful and influential magazine and fine art portrait photography. These ranged from visual artists (Picasso, Duchamp, Mondrian, Albers, et al.) to musicians (Stravinsky), writers (Capote), politicians (Kennedy), dancers (Tharp), and actors (Monroe). In short, the full spectrum of creative personalities in Western culture available to him during his lifetime.

Arnold Newman, “Marilyn Monroe, actress and singer,” Beverly Hills, California, 1962. Gelatin silver print. 14 ¾ x 16 ¾ in. Courtesy of the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

His 1945 exhibition Artists Look Like This at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, mounted while still in his twenties, paved the way for his lifetime entrée to the great minds of his day. Arnold Newman: Masterclass, the first posthumous exhibition of this work, is rife with portraits of artists from Grandma Moses to Marcel Duchamp. It is the largest exhibition of his work to date, featuring over two hundred works.

Arnold was often tagged with the label “environmental photographer” because of his sensitive use of incorporating the subject in situ. Forsaking studio work, he entered the lair of his subject, pairing the sitter with readily available personal objects. In rare occurrences, he paired personalities, as in the case of the improbable coupling of Marilyn Monroe with Carl Sandburg. The enlarged contact sheet of the meeting reads like a novel—the photographer’s edit marks indicate the dramatic moments of the meeting. Arnold recoiled at being called an environmental photographer, correctly predicting that it would pigeonhole him.

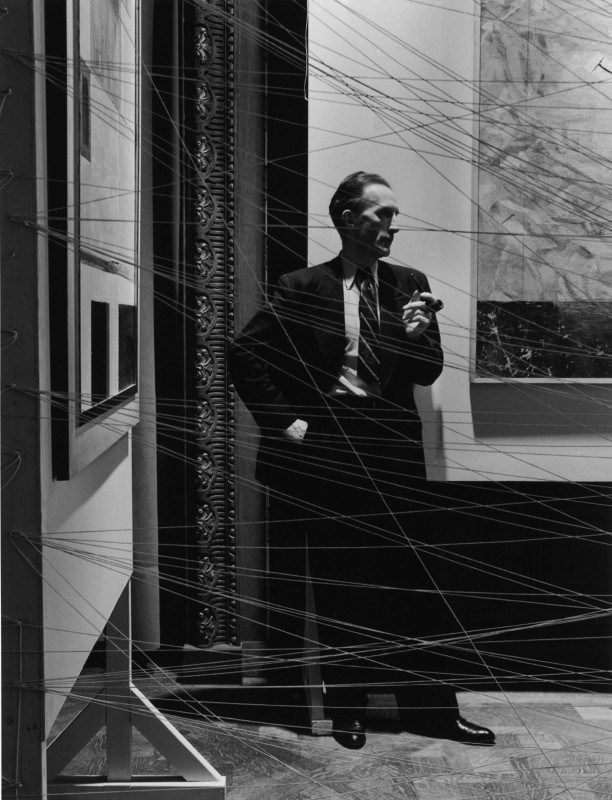

Arnold Newman, “Marcel Duchamp, painter and sculptor,” New York, 1942. Gelatin silver print. 28 1/8 x 22 5/8 in. Courtesy of the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.

He was more than just an excellent interior decorator. His work echoed the personality of his subject stripped bare of artifice, as evidenced by his highly regarded portrait of Picasso where strict attention was paid solely to the artist’s face. The contact sheets of the sitting feature the artist flanked by an array of his sculptures, but in the end the face is tightly cropped, the photographer focus squarely on the expressiveness of the subject and eliminating all else.

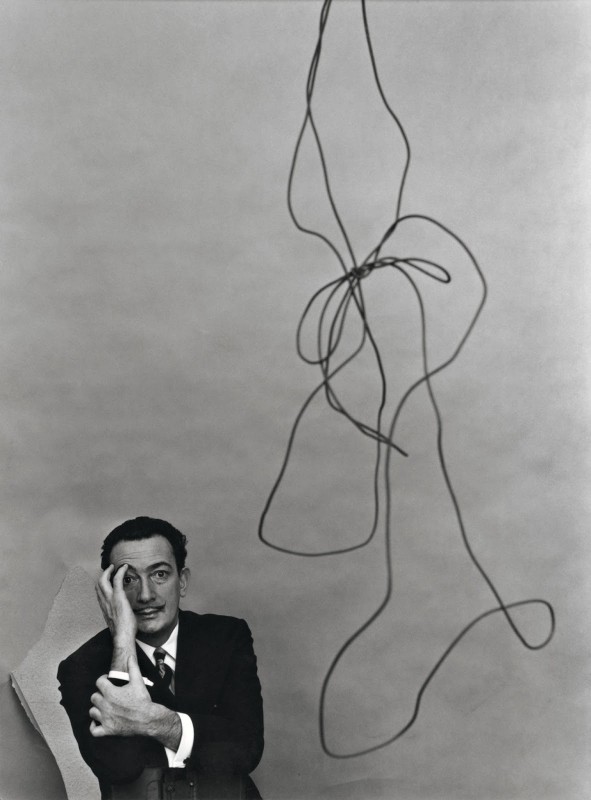

Arnold Newman, portrait of Salvador Dalí. Courtesy of the Internet.

In other portraits, composition becomes the dominant force in the selection of the final image. Newman became known as a photographer that took many shots to capture a single moment. Subtle shifts occur in the various angles explored while the session is in process. In the editing process, while examining contact sheets, balance is sought and the composition of the various black and white grounds judge the success or failure of the image. Nowhere is this better expressed than in the portrait of Piet Mondrian, where shadows and the artist’s easel vertically cut though the plane of the photograph in the manner of the painter’s own work. The final result could only have resulted from numerous efforts to capture the shadows in harmony with the desired composition.

Arnold Newman, “Igor Stravinsky, composer and conductor,” New York , 1946. Gelatin silver print. 17 15/16 x 21 1/16 in. Courtesy of the Internet.

Geometric composition is but one element of this photographer’s forte. Wall texts inform the audience of his strong suits: sensibility, a signature style, an evocation of rhythm, the use of natural light, weaving his own creativity with that of the subject, adaptation to the sitter’s habitat, and bringing the latest in contemporary painterly theory to his work.

Arnold Newman, photograph of Martha Graham. Courtesy of the Internet.

The Jewish Contemporary Museum has become particularly adept at programming in conjunction with their other exhibitions, and the events complementing the present show are no exception. Talks by nationally recognized photographer July Dater, as well as dance critic Margaret Tedesco, local artist Lisa Blatt, and photography collectors Chris McCall and Darius Himes illuminate various aspects of Arnold’s accomplishments. Films for adults and workshops for children round out the peripheral activities generated by the exhibition. An excellent catalog documents the show.

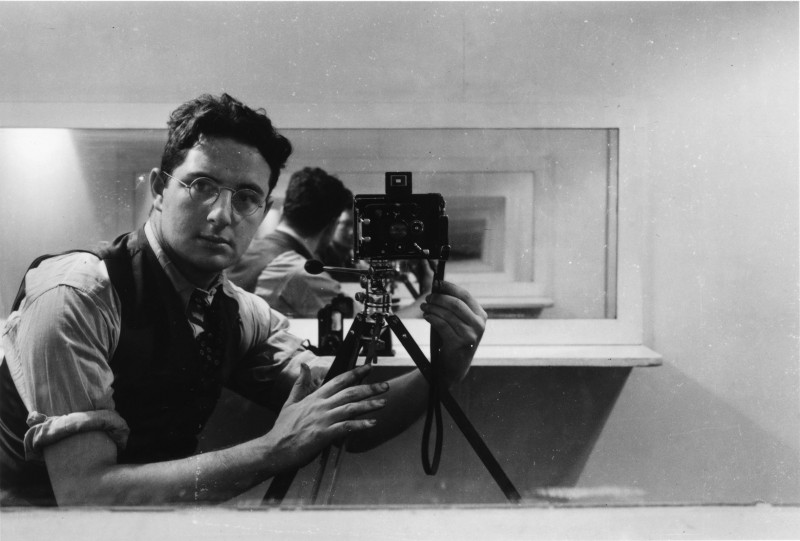

Arnold Newman, “Self‐portrait,” Philadelphia, 1938. Gelatin silver print. 14 ¾ x 16 ¾ in. Courtesy of the Contemporary Jewish Museum, San Francisco.