“For surely we shall pay for using this most powerful instrument of communication to insulate the citizenry from the hard and demanding realities which must be faced if we are to survive. I mean the word survive literally.”

—Edward R. Murrow, from his famous 1958 speech,

“Wires and Lights in a Box.”1

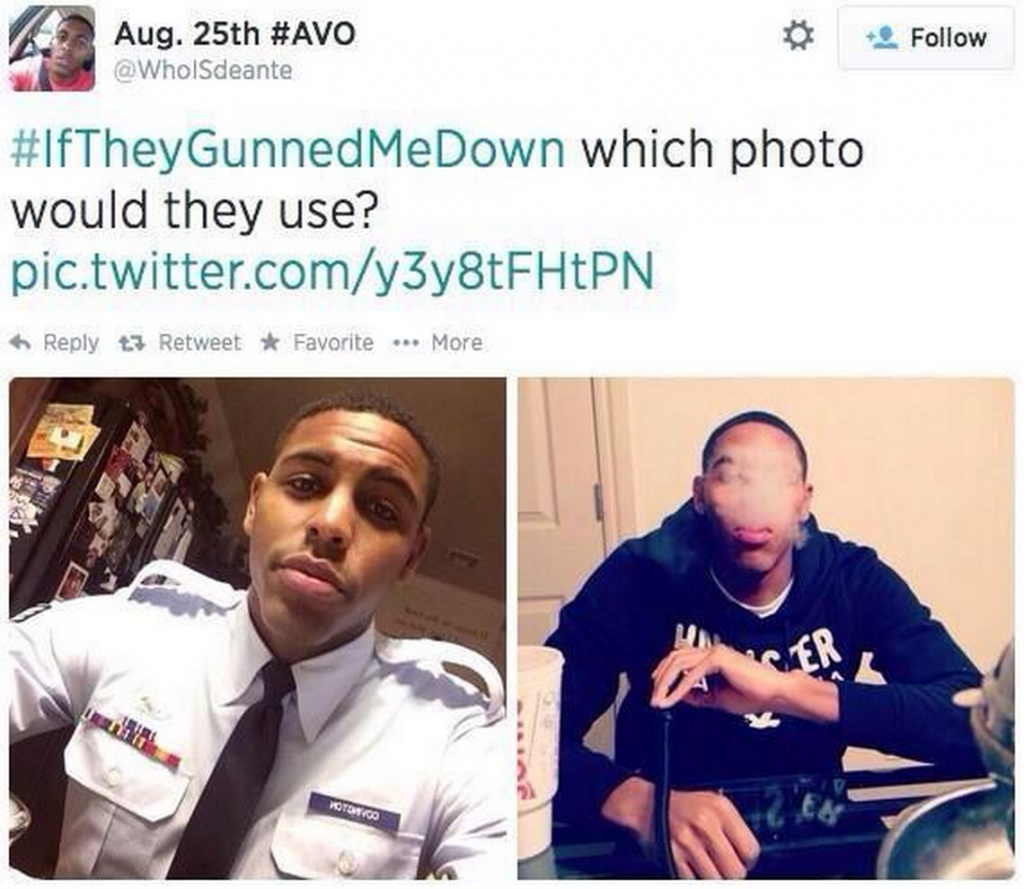

If not for social media, few of us would have ever heard of Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson, Missouri. Police kill close to one hundred African Americans every year, so Brown’s death was not deemed newsworthy. In the aftermath of the shooting of the unarmed teen, protests went on for two days before being covered by major broadcast2 media outlets: three days and nights of demonstrations before national media began a conversation about race and policing in this country. Thanks to the people of Ferguson taking to the streets and sharing their rallying cries and protests on social media using hashtags, images, videos, and impactful messaging, protesters broke through mass media silence on a topic in dire need of more attention.

Social media has been lauded for its integral role in mass protest movements around the world. Egyptians occupying Tahrir Square and Turks occupying Gezi relied heavily on Facebook and Twitter for real news—news that could indeed save their lives—that was almost entirely absent from mass media reporting. Social media has been celebrated in these instances as media by and for the people; a citizen media. But that’s not the entire picture.

Firstly, what is “citizen media”? There are many thinkers in this field, often using slightly different terminology. Courtney C. Radsch, journalist, media expert, and freedom of expression advocate calls this type of empowered social media “citizen journalism,” which she defines as:

“An alternative and activist form of newsgathering and reporting that functions outside mainstream media institutions, often as a repose to shortcomings in the professional journalistic field, that uses similar journalistic practices but is driven by different objectives and ideals and relies on alternative sources of legitimacy than traditional or mainstream journalism.” 3

To Radsch, while citizen journalism “functions outside of mainstream media institutions,” its value is seen almost entirely in relationship to external power structures, namely mass media and politicians. This is not a media by and for the people but by the people and for society, for power structures, and for change.

Looking deeper for a definition of media “by and for the people,” we find Clemencia Rodriguez, professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Oklahoma who coined the term “citizens’ media.” In Rodriguez’s book Citizens’ Media Against Armed Conflict: Disrupting Violence in Colombia, she details her findings from years of investigating media’s role in peacekeeping in Colombia, and defines citizens’ media as “those media that facilitates the transformation of individuals into citizens.”

It is important that we understand “citizen” here as separate from legal citizenship to a nation or the right to vote, but rather as a self-determined state of being, “defined by daily political action and engagement.” Rodriguez’s citizens’ media stands in contrast to Radsch’s citizen journalism because the focus is internal and based on hyper-local transformation. She believes that “the goal is not to communicate, express, or inform, but instead to perform all those local identities, values, ways of life, cultural practices, and forms of interaction.” In this way, while there are many examples of citizens filling in for the inadequacies of the press, Rodriguez’s citizens’ media is a truly individually run and focused media, and consequently, is much harder to find on social media by design.

I define social media as a media environment that enables users to connect with each other as well as create and share content. While some definitions of social media focus solely on the users’ production of and interaction with media, we cannot forget the hardware and software that house that activity. In this understanding, social media from, for example, a Russian user of VKontakte, Russia’s most popular social network, is to be understood as different from that of a user on Twitter living in Iceland. Local laws can affect what is deemed legal to say or do on a platform. Every platform has differing affordances like file formats, text size, and types of filtering. Furthermore, the cultural makeup and diversity of the community of users on differing platforms make for very different media.

Social media platforms are mediators for communication. The algorithms they use to select what you see (what posts on Facebook you see, what is “trending” on Twitter, who you should follow, etc.) are often based on user data, but users are not in control. Emily Bell, the director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia, writes, “The most powerful distributor of news now is . . . an algorithm governing how items are displayed to the billion active users on Facebook.”4 Social networks are increasingly becoming the arbiters of political discourse, news, and interpersonal communications, all of which rely on profiting from the data you share. For this reason, we are seeing a growing need for more transparent social media platforms.

Christian Sandvig, faculty associate of the Berkman Center for Internet & Society at Harvard, writes, “In effect Facebook is re-ordering your conversations with your friends and family on the basis of whether or not someone mentioned Coke, Levi’s, and Anheuser Busch.” Many users shrug this off as it has almost become an accepted given of free online media, but Sandvig pushes harder. “Corrupt personalization is the process by which your attention is drawn to interests that are not your own.” Just as author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie said in her TED talk, “Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person, but to make it the definitive story of that person.”5 Subtle affordances of platforms can steer or invent new stories about us. The result is antithetical to a media by and for the people.

Furthermore, all of this “user-generated content,” which is actually very affected by the platform, sits inside of a complex infrastructure few of us know anything about, let alone control. When compared to how few channels there were on TV not that long ago, many celebrate the number of blogs and social media accounts as evidence of current media’s diversification. However, the most fundamental infrastructure of the Internet consists of only thirteen tier 1 Networks,6 eight of which are based in the U.S. These are the cables through which all our data passes. So, can we really say our data?

Yes and no. We do own our data in many ways. We can create anything legal, share it in a way the social network allows, and delete it if we choose. We can sell the images we add to other venues. However, many platforms keep and profit from the data, even if you “delete” it. While we can sell the images we have shared, so too is the social platform selling information and even the images themselves.

Bruce Schneier, a computer security and privacy expert, said that these technologies do magnify power, but governments and corporations have more power to magnify, thereby continuing the imbalance. Schneier said, “At a most fundamental model, we are tenant farming for companies like Google. We are on their land producing data.”7 Tenant farming is a notoriously unjust economic and power relationship where an institution or individual with deep wealth and power negotiates an agreement with someone with little wealth or power. Needless to say, the owner of the land usually profits greatly. As Mark Zuckerberg’s net worth passes $34 billion8 after founding Facebook only ten years ago, the metaphor rings true.

But does this honestly matter? Absolutely. While people of course make media by and for themselves even within capital-driven systems, understanding the influences of those systems and how they might interrupt or override the user’s goals is integral to our understanding citizens’ media. Planning protests, visiting legal organizations, using privacy software, attending legal demonstrations, etc., are all acts that, while historically protected under our constitution, have come to merit targeted surveillance. The repercussions and fear associated with this type of surveillance can be even worse outside of the U.S. The right to free speech, to privacy, and to assembly, i.e., the bedrocks of democracy, which are integral to a robust citizens’ media, are being stripped by governments and corporations en masse.

While nobody seriously debates the influence of pens vs. pencils on discourse, the technologies used for discussion have changed dramatically. The undeniable value of keeping a journal, writing love letters, and writing calls to action remains. Nevertheless, the tools we use to do so work in very different ways today. Issues of surveillance arise throughout these systems that stand to moot the concrete opportunities for empowerment they present.

Rodriguez spends a lot of energy emphasizing the off-air aspects of citizens’ media. While on-air programming was the obvious product, workshops, conferences, parties, public screenings, and more were integral aspects of Rodriguez’s idea of citizens’ media. Similarly, given the limitations of citizens’ media on social media, I believe that workshops, offline meetings, legal battles, privacy tools, and institutional support become integral to a citizens’ media. Without serious improvements in digital literacy for the greater population, we remain at the whims of larger corporate and governmental interests.

There is a plethora of organizations enabling citizens to speak and use media safely and effectively, and their partnership with all of us holds the most power to make social media safe for citizens. Organizations like WITNESS, the Center for Media Justice, Prometheus Radio Project, Free Press, Freedom of the Press Foundation, Electronic Frontier Foundation, International Modern Media Institute, Reporters Without Borders, Committee to Protect Journalists, Global Voices, and so many more realize that digital literacy extends beyond understanding how to post online or send an email.

What few users understand and have time to learn is how many laws, interests, technical issues, and even issues of infrastructure intersect with our daily communications. Fighting for municipal broadband, data retention laws, issues of jurisdiction of networked content, algorithmic filtering, etc., all intersect when considering a citizens’ media online, and most users, including me, need and deserve better help navigating than the corporations offering us Internet and social platforms are willing to offer.

The media that we consume is constantly reestablishing who we are and what type of society we want to be. Citizens’ media is a democratic and free media, truly representative of its co-creators and therefore best suited to represent our ideas, cultures, and debates. While social media has increasingly become the home for our society’s conversations, it has also become a confluence of private and governmental interests obfuscated by law and code.

We must listen to the likes of Adichie and Schneier and understand that these issues matter, and will only matter more the larger the role technology plays in shaping public discourse. We need a broader and deeper conversation about what appropriate free speech laws are and to what extent these platforms can govern their users. We need stronger digital literacy and greater transparency around how these platforms affect our dialogue. A citizens’ media is an ideal we have only glimpsed on social media platforms, but one that still remains immeasurably important to pursue.

_____

1)www.rtdna.org/content/edward_r_murrow_s_1958_wires_lights_in_a_box_speech#.UrkNdI050mx

2) http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/08/20/cable-twitter-picked-up-ferguson-story-at-a-similar-clip/

3)http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2161601

4)http://www.theguardian.com/media/media-blog/2014/aug/31/tech-giants-facebook-twitter-algorithm-editorial-values

5)http://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story?language=en

6) http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tier_1_network

7)http://threatpost.com/bruce-schneier-technology-magnifies-power-in-surveillance-era/105365#sthash.SKA2TEoc.dpuf

8) http://www.forbes.com/profile/mark-zuckerberg/