By Jasmine Moorhead

“Establishing Equilibriam” (in process), a document of performance painting, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Jancar Gallery, Los Angeles.

In spite of her wide-ranging work, Tricia Lawless Murray’s artistic mission is actually very specific: a thorough exploration and re-siting of the feminist body in a geo-psychic-historical space. Her art works have taken many forms including performance, sculpture, drawing, collage, video, and most dominantly photography, which she uses simultaneously for its own formal aesthetic qualities as well as a documentary receptacle for her performances. As someone with a background in dance, who also studied art history at Cal Berkeley before years later going on to get her MFA at CCA in 2008, Lawless Murray has always utilized a variety of art forms and engaged specific artist as levers to pry open and uncover her own ontology around this purpose.

Up until the present, the predominant lever for Lawless Murray has been Marcel Duchamp, whose work around gender is well known and yet somehow also undervalued. This aspect of Duchamp’s oeuvre may well be the only chess game he left without knowing how the endgame played out, and Lawless Murray has taken it up. Her MFA thesis work, “After Duchamp” (2008), imagined Duchamp’s “The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass)” (1915-23) as a performative sculpture, whose power structure was subverted by her role as the chocolate grinder, a many-tubed carousel of both scatological and orgasmic release. A more recent series from 2012, titled “The Sea Folded Its Layers Around Her”, echoed and answered Duchamp’s last work, “Étant Donnés,” or “Given” (1946-66), a life-sized diorama featuring a hairless female mannequin in a kitschy wooded scene by a waterfall, which can only be seen through a couple of small peepholes in a large wood door. Comprising self-portraits mixed with collages from 1950s to 1970s-era magazine scenes, presented by themselves or in peephole boxes, Lawless Murray’s series features her own body as a lithe stand-in for Duchamp’s mannequin. She emphasizes a playful and soft eroticism, imbuing her work with a life force, which is almost completely absent in that of Duchamp’s. Whereas Duchamp‘s mannequin is positioned physically apart from the waterfall, Lawless Murray’s figure lies in the feminine water, “being held by the sea, psychologically,” as she has described. The shift into life is significant both for Lawless Murray personally and art historically. There is a warm, yellow light around the figures in that series that we now can understand as a signal of the quiet emergence of a new energy and direction, as well as a shift in the tide of the match. Perhaps it is not the endgame after all.

“The Sea Folded Its Layers Around Her,” 2012, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Jancar Gallery, Los Angeles.

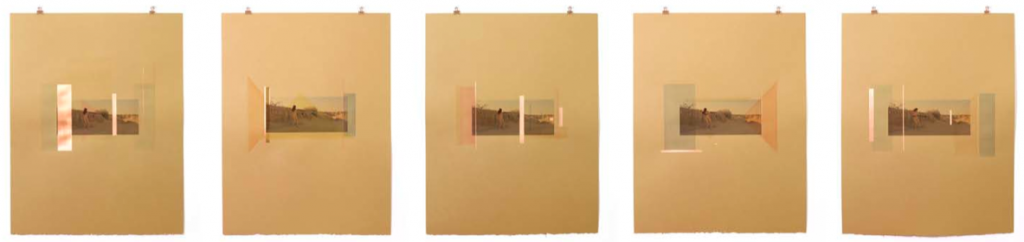

First, consider a piece consisting of five photographs of 2013, which she titled “Nonobjectivity Drew Me Forth.” In these, having taken her fill of water and been renewed by it, she emerges in the desert. She photographs herself as a latter-day Annie Oakley (1860-1926), a genius markswoman and star member for many years of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, who was known as “Little Sure Shot.” An early feminist, Oakley believed that women should know how to defend themselves.

In this work, Lawless Murray has photographed herself in the desert shooting a shotgun at an unseen target. Naked and abstracted, she is the Duchamp mannequin come fully to life. In each segment of the piece, the artist has framed different geometric shapes of transparent hues of yellow, blue, or violet around the photographs. At first glance this seems merely to be an attempt to architecturally position the photo frame, but the title of the work clues us into her larger intentions here. In the previous Duchamp-influenced series and in a transition work also of 2013 titled “You Ain’t Going Nowhere,” she had subtly engaged the triangle, both the shape signifying the vagina and its fulcrum of the empty space between the legs. Now, in “Nonobjectivity Drew Me Forth,” this triangle is starting to form a protective glow around her in these works, suggesting a spiritual light that serves to philosophically position the figure and her action.

“The Sea Folded Its Layers Around Her,” 2012, installation view. Courtesy the artist and Jancar Gallery, Los Angeles.

This piece in fact signifies the true beginning of Lawless Murray’s integration of a new focus in her work, that of Hilma af Klint (1862-1944), a contemporary of Oakley’s, though a continent away in Sweden. In her lifetime, Klint was known for her landscape paintings, but working in secret she was making perhaps the first truly abstract art. She created bold, slightly off-kilter geometric forms, drawing heavily on the teachings of Theosophy, which emphasized the spiritual nature of form and its relationship to the cosmos and esoteric knowledge.

Lawless Murray grew up in Point Loma, CA, where one of the main American branches of Theosophy was located. Headed by Katherine Tingley, this theosophical group created the first Greek-style amphitheater in the United States and invited performance as a way toward spiritual connection. Lawless Murray, as a young girl, was exposed to the ideas of Theosophy through one of Tingley’s modern-day adherents. Although Lawless Murray’s attraction to HIlma af Klint ultimately derives from a shared aesthetic goal, Klint’s experiences with theosophy piqued her curiosity.

“Nonobjectivity Drew Me Forth,” mixed media, five works at 21″x16″ each, 2013. Courtesy the artist and Jancar Gallery, Los Angeles.

Lawless Murray’s current project titled “Establishing Equilibrium” is an ambitious 21st-century exploration of these overlaps of performance, geometric abstraction, and a search for esoteric knowledge—correspondences that were much more clear 100 years ago in Hilma af Klint’s era but were obscured and subdivided by much of 20th-century art and the critical language around it. She is melding the spiritually infused geometric forms of Hilma af Klint while re-engaging with a performance by David Askevold (1940-2008) called “Taming Expansion” (1971).

Existing only in print, as a description of the work and diagrams, Askevold’s piece called for six performers standing equidistant from one another around a circle formed by the points of a six-pointed star. Each performer held a branch out to a coiled mass of snakes in the circle’s center in order to “tame” them. According to Askevold, whom his student Mike Kelley once admiringly described as “a difficult conceptualist,” the performance was set up and then thwarted by the fact that one of the participants was bitten and in the ensuing melee the film was destroyed. (According to other sources the performance never actually took place.)

Regardless, in “Establishing Equilibrium,” Lawless Murray now brings a very different intention to the forms of the circle and the star composed of intersecting triangles. No longer content with the spectacle of postmodern conceptual performance, Lawless Murray is seeking grounding and enlightenment by reuniting the conceptual with the esoteric, blending a lineage that goes back hundreds, if not thousands, of years, threading back through to a time when ritual and art, spirit and body, mind and cosmos, were ones. This is potentially the end of Duchamp’s endgame, one he, perhaps, in his all-knowing way, deliberately set us on a path away from, but to which, happily now, Tricia Lawless Murray has returned.

This artist highlight is selected from Issue 15 of SFAQ.

Previous SFAQ Artist Highlights:

Artist Highlight: KEMBRA PFAHLER