This interview was originally published in SFAQ issue 11 (November 2012–January 2013).

In 1968 Paula Cooper opened the first commercial gallery below Houston Street in New York, a warehouse and light manufacturing district where a number of artists lived and worked. It would, of course, become known as SoHo. Her gallery was associated with leading Minimal and Conceptual artists, such as Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Jackie Winsor, and Jennifer Bartlett, and was also a venue for avant-garde music and performance as well as political causes. She is known for her close relationship with artists, many of whom have stayed with the gallery since the beginning. However, she is also always on the lookout for new talent and has recently taken on several young artists. Cooper has seen the art world expand and change beyond what anyone could have imagined, but has managed to retain her charm, integrity, and equilibrium. I talked with her in her Chelsea gallery on September 19, 2012.

Paula, I read something recently I hadn’t known about you—that you had a gallery called Paula Johnson. Was that your maiden name?

Yes. In 1962 I opened a small gallery in my home.

And this was before you opened your gallery in SoHo?

Yes, but it was not my first gallery experience. From 1959-1961 I worked at World House Gallery, a space that was designed by Frederick Kiesler. It was a great experience. We showed Giacometti, Ernst, Dubuffet, Bacon. . . . The first show I installed was Morandi. It was a fantastic experience.

Portrait of Paula Cooper, May 17, 1995. Photograph by Eric Boman. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

And then you worked at Park Place, right?

Yes. Park Pace was an artists’ cooperative gallery on West Broadway at what is now La Guardia Place. I got to know a lot of young artists there, like Robert Grosvenor and Mark di Suvero. After Park Place, when I started my own gallery, I had a few pieces of Mark’s, but Dick Bellamy devoted his life to him, really. Now that we’ve started working together over forty years later, it’s so nice. I am not afraid of him anymore [laughter].

Then you opened the first commercial gallery south of Houston in what was to become SoHo. Wasn’t that at the same time that Ivan Karp opened O.K. Harris in the same area?

No, I opened in 1968, one or two years before Ivan. I didn’t like uptown. I wanted to be in the part of the city where the artists lived. Everybody thought I was crazy.

Did you study art history?

Yes, of course, but I never received a formal degree. At the age of 16 I moved to Europe with my family and lived there for nearly four years. I studied in Athens, Munich, and Paris. When I returned to the US, I went to Goucher College, where I also took studio courses, and then in New York, at the Institute here as a non-matriculated student.

Your father was in the military, right?

He worked for the government.

You still represent some of the same artists that you started with, like Carl Andre, Sol LeWitt, Bob Grosvenor. . . .

I know—it’s wonderful.

At first you concentrated on Minimal and Conceptual artists. Now your program seems more eclectic. How would you characterize it?

I don’t think it’s really as eclectic as it may seem.

Tauba Auerbach, Untitled (Fold), 2012. Acrylic paint on canvas on wooden stretcher, 64 x 48 inches. © Tauba Auerbach. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

And recently you have taken on some new, younger artists like Kelley Walker, Carey Young, Walid Raad, Justin Matherly, and Tauba Auerbach. Tauba studied art in San Francisco. I think she is interesting. How do you select artists to show?

In several instances, they have worked in the gallery (Lynda Benglis, Bob Gober, and Justin Matherly) or have been recommended by other artists. I used to be very slow to make a commitment—would have an artist in a two- or three-person show, live with the work a bit, and then decide.

In the past, there was a stigma against showing California artists in New York. Now no one seems to care where an artist lives.

Just about everyone I ever worked with has been from another part of the country. It’s true that now it’s no big deal, but the difference was that Californian artists stayed in California, whereas those from Ohio or Kansas, for example, moved to New York. It was possible to have a career in Los Angeles or San Francisco, but not anywhere else.

Chicago, maybe.

Yes, but the artists there were so different. They could survive.

One thing that has always distinguished your gallery is that you make it available for all kinds of events, political and artistic.

The gallery opened with an exhibition to benefit the Student Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam and Veterans Against the War. Some artists included were Donald Judd, Robert Ryman, Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Dan Flavin, Bob Huot, and Sol LeWitt, several of whom I would later represent.

I know Philip Glass and Mabou Mines performed in your gallery early on. And you continue to host events.

Yes, we do. When I had my first little gallery I had a friend, Steve Pepper, who was an art historian who eventually taught at Johns Hopkins. He was part of Red Grooms and Mimi Gross’s group. He always believed in also making the gallery a place for performances and events. He had a space on Broadway and that seemed so logical and appealing. Also, Park Place was the most generous of spaces; they would always invite unaffiliated artists to participate in shows there. My most recent event here was a conversation with Philip Glass, Robert Wilson, Christopher Knowles, and Lucinda Childs on the occasion of a show, Einstein on the Beach, which is being performed again. It was wonderful.

Yes, I am looking forward to seeing “Einstein” when it comes to Berkeley next month.

We also have readings at 192 Books, a bookstore that my husband and I have opened. Some of the readers have been Michael Ondaatje, Alice Munroe, John Ashbery, Geof Dyer, and most recently, Martin Amis.

Getting back to how the art world has changed . . . it is remarkable that not only have you endured but thrived. For example, Christian Marclay’s The Clock; what a triumph! Did you have any idea that it would take off the way it did?

No, but I thought his previous multiscreen work, Video Quartet, was beautiful and brilliant. A short video, Telephones was really the beginning.

Installation view, The Clock, Christian Marclay at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2010. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

Yes, I saw Video Quartet at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), and I agree, and the UC Berkeley Art Museum owns Telephones.

The Clock is brilliant and amazing, it’s so ambitious—to have had the idea and actually realize it!

I was lucky to have seen it in your gallery before it became the sensation it did, before the lines. Now, more people will have access to it; it will be shown at Museum of Modern Art in New York soon, right?

Yes, and it was recently shown at Lincoln Center and will be at SFMOMA in April 2013.

Haven’t various museums shared in the purchase of The Clock?

Yes, and I think it’s smart of museums to share videos since they are not showing them all the time.

It makes sense.

Yes, it’s more exposure for the work and reaches a broader audience.

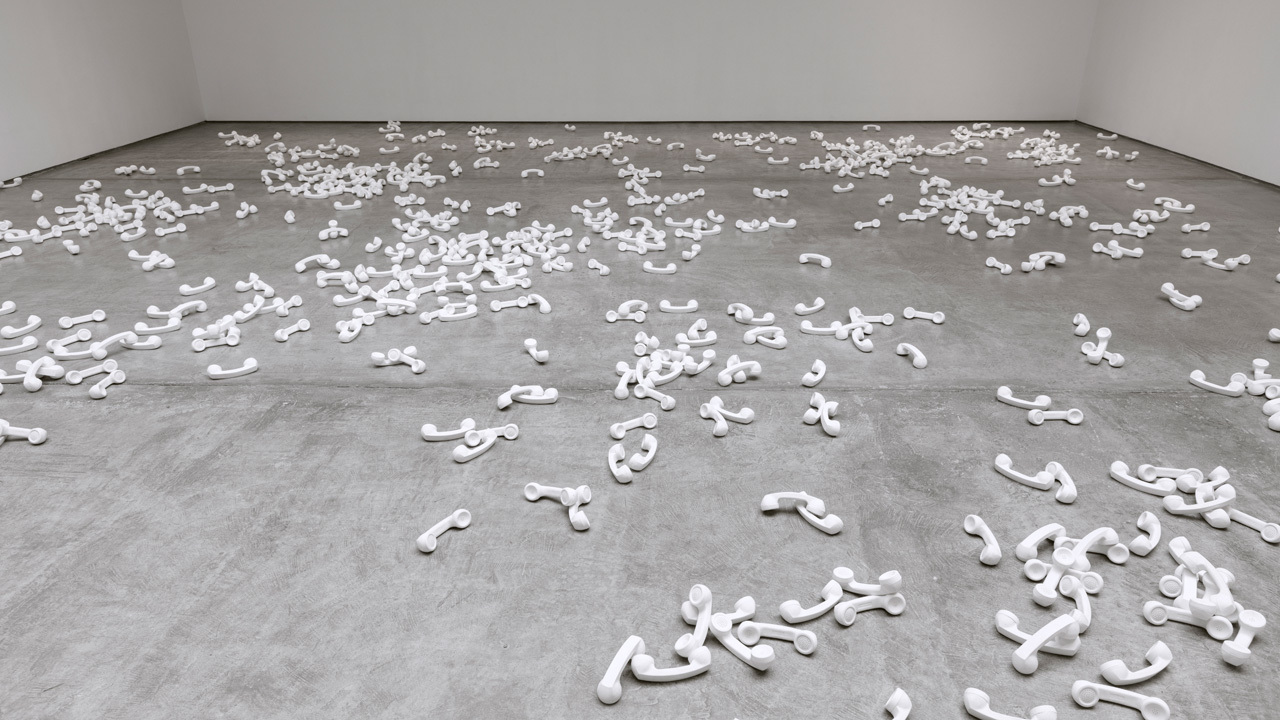

Installation view, Phones, Christian Marclay at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2017. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

Installation view, Phones, Christian Marclay at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2017. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

How do you deal with this new hyper-commercial and vast art world?

I just focus on what I do, I always have—it is the only way I can survive. The art world is so huge now; it’s so very different. It’s just like everything else; it’s all about money, money, money. But everything is, isn’t it?

And then there’s the proliferation of art fairs to deal with.

We started doing the Basel Art Fair a while ago, thinking I’d better do it at least once in my life, and here we are twelve or fifteen years later, and we are still participating. Lately, I’ve gotten sort of competitive, I want the booth to look really good—like an exhibition, not a shop display.

I’ve read that some galleries do practically all of them and do most of their business at fairs.

Yes, and now there are fairs in Rio, Dubai, Hong Kong, etc, etc.

The Chicago Art Fair is in a few days. Is your gallery participating in that?

No, We only do the two Basels—Switzerland and Miami—and FIAC, because I love Paris so much.

Wasn’t there a time when you were considering opening a space in Paris? I remember running into you there once, when you were looking around. You were with Kiki Smith’s sister.

Yes, Seton. She lived there.

What made you decide not to?

Well, things in Paris changed economically and it seemed too much to handle. We had even started discussing renovation of a space on rue du Tresor with an architect. I thought the street name augured well.

[Laughter]

But, it kind of slipped away. I had previously done something in Paris with Yvon Lambert. We traded galleries. I was in Paris for two months with my children.

And, I seem to remember you had a gallery in Los Angeles briefly.

Yes, I rented Riko Mizuno’s space on La Cienega, which Robert Irwin had designed. Helen Tworkov managed it, and I would alternate weeks in New York and L.A.

Artists come and go—how do you deal with that?

Well, it is always hard losing artists, but two artists who were showing with Gagosian—Paul Pfeiffer and Mark di Suvero—are now with me.

What motivates you, keeps you going?

I love every aspect of what I do—I’m very fortunate.

2018 marks Paula Cooper Gallery’s 50th year of operation. In celebration, the gallery will be sharing photographs from their archives on 50years-paulacoopergallery.com and on the Paula Cooper Gallery Instagram.

Paula Cooper Gallery

1968

Installation view, Benefit For The Student Mobilization Committee To End The War in Vietnam featuring Carl Andre, Jo Baer, Bob Barry, Bill Bollinger, Dan Flavin, Robert Huot, Will Insley, Donald Judd, David Lee, Sol LeWitt, Robert Mangold, Robert Murray, Doug Ohlson, and Robert Ryman at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 1968. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

1978

Installation view, Group Exhibition featuring Richard Artschwager, Jennifer Bartlett, Lynda Benglis, Robert Grosvenor, Michael Hurson, Elizabeth Murray, Alan Shields, and Kes Zapkus at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 1978. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

1988

Installation view, Recent Sculpture, Robert Grosvenor at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 1988. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

1998

Installation view, Travel and Leisure featuring Carl Andre, Jonathan Borofsky, Peter Campus, Michael Hurson, Yayoi Kusama, Julian Lethbridge, Sherrie Levine, and Adrian Piper at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 1998. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

2008

Installation view, Kelley Walker at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2008. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.

2018

Installation view, Jackie Winsor and Linnea Kniaz at Paula Cooper Gallery, New York, 2018. Courtesy of Paula Cooper Gallery.