This interview was originally published in SFAQ issue 9 (May–July 2012).

I wanted to meet Anna Halprin due to my interest in Fluxus. George Maciunas, the driving force behind the movement, had just opened the AG Gallery (1961) and was seeking information on the avant-garde. In stumbled a recent transplant from the Bay Area, experimental musician and composer LaMonte Young, seeking to publish a sheaf of “performance scores” gathered while associated with dancer/choreographer Anna Halprin, who had been experimenting with “task” oriented works; shifting the focus of radical art in the fifties from “expressive” works, to “concrete” actions found in everyday life. This resulted in the first Fluxus project, the publishing of An Anthology, edited by Young and designed by Maciunas.

Like her innovative counterparts at Black Mountain College, Anna and her husband Lawrence, were schooled by Bauhaus émigré masters. While BMC had Albers, Harvard, where Lawrence obtained his Ph.D. in Landscape Architecture, was graced by the presence of Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius, teaching at the Graduate School of Design. Referring to the artists arising from BMC, Halprin relates, “They went in one direction, and Larry and I went in another. Where their art became conceptual, our art became organic and nature oriented.” This telling comment reveals all.

Anna was building a career in dance, having graduated from the University of Wisconsin at Madison, and was invited by noted choreographer Doris Humphrey to join her on Broadway in a revue featuring Burl Ives. Humphrey was a Denishawn student (founded by Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in 1915), as was Martha Graham and Charles Weidman. Other Denishawn dancers boarded in Halprin’s childhood home, giving Anna direct access to the flowering of Modern Dance in America.

Back from his WW II service, Lawrence had an opportunity to practice in the Bay Area, luring Anna to Kentfield with the promise of constructing a “dance deck” connected to the Halprin residence at the Northern base of Mt. Tamalpais.

There was a dearth of Bay Area dance opportunities in the late 1940s when Anna arrived, but her direction in movement attracted young dancers and choreographers from the East Coast. Yvonne Rainer, Trisha Brown, Robert Morris, and Simone Forti (as well as Merce Cunningham, a former Martha Graham dancer, who had been forging his own style), found their way to the dance deck. Their experimentation in the fifties led to the creation of the Judson Dance Theater in the Sixties, owing much to Anna’s workshops, which catapulted dance beyond Modernism.

This new Post-Modern style, forged in the forests of Marin, encouraged not only dancers, but composers of new music, and ultimately George Maciunas (1962), who took the event scores gathered on the West Coast by Halprin and Young, performing them in Germany with experimental visual artists Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Emmett Williams, Nam June Paik, and Joseph Beuys.

In the Sixties, Anna extended the confines of the dance venue from the stage to the streets. Treating theaters as environments, she explored nooks and crannies neglected by others. Invading the spectator’s space, inflicting discomfort on some of her audience, Anna began to examine the role of the spectator and commenced incorporating the audience into the work.

Audience involvement was further enhanced when Anna was confronted with her own mortality after being diagnosed with cancer in 1972. “Who are you doing this for? Why are you doing it? And what difference will it make in anybody’s life? You start asking those questions, it leads you to a different process.”

This “different process” has yet to be fully explored or understood. It can take an experimental artist like Anna Halprin decades to be fully appreciated, if at all. But, hers is a remarkable accomplishment.

Most artists seek to transform themselves through their art—either spiritually or financially. Choose your motivation. Halprin goes beyond that. Transform herself, yes. If nothing else, her remarkable recovery from several bouts of cancer has reshaped her appreciation of the human body’s durability.

However, it is in the transformation of others that Halprin distinguishes herself. For Anna, the audience is an integral part the work. Their presence and role is always taken into account. In Anna’s hands, artistic creation becomes ritual capable of changing those engaged in the process. Art is not an activity separate from life but central to its completion.

[Anna contributed the interview’s subtitles and additional poignant information to our original conversation.]

Early Life and Training

JH: What interests me about your childhood is how supportive your mother was, in that you were starting to take dance lessons, and your mother invited dancers to stay in the family home.

AH: I grew up in that era where mothers mostly stayed at home and tended to their families, and I really bene ted from the care and attention she gave me. My mother was a very sweet, benevolent person. She never objected to my dancing; because I was interested in it, she encouraged it.

When my brothers left the house, I was an only child. She wanted me to have a sister-like relationship with other people interested in dance, so she invited some dance teachers, who were hired by a woman by the name of Alicia Pratt, who would bring dancers into our little community. Alicia had this school—the Pratt School—and she hired teachers, who were “starving,” because there was no work, there was no money in it, and they would come and live in Winnetka, Illinois.

Some of these women had been dancers with the Denishawn Company. I was intrigued by all these exotic dances, so that was where I got my training when my mother saw I didn’t take to ballet very well. We did interpretations of American Indian dances. It was interpretive dance. We would interpret American Indians, nautch girls, all kinds of fantasies. That appealed to me.

These teachers lived with us in our home so I could have companions and other humans who were interested in what I was interested in, because obviously, my brothers were on an entirely different wavelength than I was. My mother was a very simple person. She had no higher education, and no introduction to speci c arts, but she took me to art museums, because she had the feeling I was interested in art. I had a very nice, encouraging childhood.

Aside from the companionship afforded by the dancers coming into your home, you were able to observe firsthand what it was like to be a dancer.

Which honestly wasn’t very attractive at the time. This was the one thing that kind of frightened my mother a little bit, because none of these women were married. In those days, you couldn’t be married and have a career. My mother couldn’t imagine me not being married and having a family. So, that worried her. My father wanted me to play the harp.

But they did allow you to go away to university—the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Here’s an interesting thing, which is kind of strange for people now to understand. I tried to get into Bennington, because that was the only school I knew about where I could get into somebody’s company. Anna Sokolow and Doris Humphrey were at Bennington at the time.

So, you had to fill out applications, and you had to fill in your religion. Every time I said I was Jewish, I noticed I didn’t get in, even though I had already been dancing semi-professionally at the World’s Fair in Chicago, and I’d won all kinds of awards as a teenager. I thought it was kind of strange that I was having trouble getting into Bennington. Then I found out that they had a Jewish quota and this was why I wasn’t getting in. Obviously, a lot of Jewish kids wanted to go to Bennington, because it was such a liberal school, and it attracted the liberal minded Jewish community.

I was pretty devastated, because I had been invited to join Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman’s Dance Company, but I couldn’t do that, because I had promised my parents I would go to college. It was something they never had an opportunity to do. My father never went to school, period. I’m first generation. So, you know, when one’s parents said, “This is what we want you to do,” you did it.

Then a friend of the family, who was an educator, had heard that there was a dance major at the University of Wisconsin, which was right next door to where we lived. I was reluctant, but it turned out to be an incredible blessing, because I had the most intelligent brilliant woman for a dance teacher—Margaret H’Doubler. She didn’t dance at all. She was a philosopher and really knew about art. She was influenced by people like John Dewey, [Alfred North] White- head . . . so, the whole idea of learning through experience. . . .

She was a biologist, too.

Yes, she was originally a biologist. Because of her interest in dance as a human experience that was vital to all humanity, she had us do dissection for a year, which at the time was a little overwhelming. I didn’t realize at the time how vital that would be to my growth, and in my quest for independence from the contemporary dance styles. It gave me a foundation to start from scratch.

The Fifties

AH: Okay, now, this may be a little different, but you said you were interested in the Fifties, so let me tell you the story about the Fifties. When I came here I left New York. I was in “Sing Out Sweet Land” with Burl Ives. . . .

JH: . . . on Broadway.

Yeah. I was in that for almost a year. When I came to California, Martha Graham and Bethesbee de Rothchild came to visit my husband Larry. Martha Graham was being supported by Bethesbee de Rothchild. She gave a performance here, and Bethesbee came with her. And Bethesbee said, “While I’m here, I want to visit Lawrence Halprin.” He had done so many sites in Jerusalem and was well-known. She came over and saw I was a dancer, and she said, “Dance for me.”

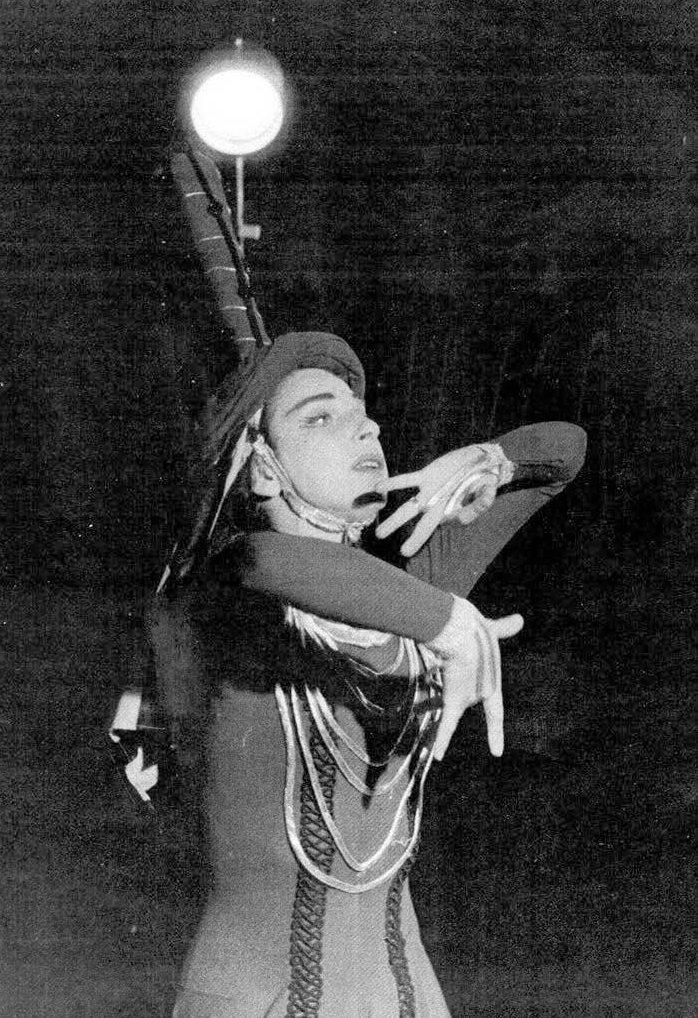

I did a piece called, “The Prophetess,” and she was sufficiently impressed that she invited me to the ANTA [American National Theatre and Academy], a three-week presentation of Modern Dance [1955]. All the people in the festival except me were from New York City. I was the only so-called “outsider,” even though I was doing modern dance and had been very influenced by Doris Humphrey . . . Martha Graham I was never influenced by, but I was by Doris.

Anna Halprin, The Prophetess, 1955. Courtesy of Anna Halprin.

Watching that festival for three weeks, I not only got bored, but I got angry. I got angry and suddenly realized that this is not what I wanted to be doing, because everybody in Martha Graham’s group—they all looked just like Martha Graham. And everybody in Hanya Holm’s group—they all looked like Hanya Holm. The same thing with Doris Humphrey. Even though we were really good friends, I thought, “Oh my God, something’s wrong here. This is just like ballet. It’s very hierarchical. It’s not my philosophy of how people should relate to each other. I don’t like this.”

So, when I came back, I felt totally alone. There was nothing going on here in dance. Maybe there was a Mills College Dance Department, but it wasn’t anything that would stimulate my interest. So I was absolutely alone. It took me a few years to find my own way.

Did the Living Theater or the Open Theater have an influence on you?

I loved Joseph and the Open Theater, but they didn’t influence me. We were doing a similar thing. I worked with Joseph, but he didn’t influence me. The only person who influenced me was Larry . . . and my teacher Margaret H’Doubler.

But Larry—he influenced me. And I influenced him . . . You have to be careful about who influences you, because you get into fashions again.You’re taking something outward and sticking it on. You really have to be original.

So, in the fifties, when I felt unclear about my directions in dance, I began plugging into other people living in California, people like James Broughton, the [San Francisco] Tape Music Center, Morton Subotnic, Charles Ross, Michael McClure. None of these people were famous at the time. I shouldn’t say famous, that’s the wrong word. None of these people were acknowledged. Michael McClure . . . all of them.

Gradually, we began to form a collective, because the Tape Music Center was in the same building that I discovered and rented—321 Divisadero Street. The Tape Music Center and my activities became the cultural center of San Francisco at that time. That was the only place—if people like the Living Theater would come through or the Involve Group from Israel—they would all meet and rehearse at 321 Divisadero Street.

Is the Tape Music Center familiar to you? That’s where Terry Riley, LaMonte Young, and Pauline Oliveros all worked. All the musicians would be drawn to the Tape Music Center, and we had two huge studios, one was like an auditorium where we could do presentations.

The fifties were a period where we were finding ourselves . . . beginning to team up with other artists. It was an opportunity to start exploring. But the actual work for the public wasn’t coming out until the end of the Fifties and all throughout the Sixties. So when you said you wanted to talk to me about the fifties—that was just a period of groping and discovering and trying to find our directions. The results of all that was in the sixties.

Life with Lawrence Halprin

JH: In the fifties, you were still developing a philosophy, and it seemed to center on “tasks” and “scores.” I think this was very important. But, I’d like to backtrack a bit and talk about your meeting with Lawrence at school, him going on to Harvard, and your joining him there and meeting the Bauhaus artists.

AH: Well, Larry has a long history. When he was just sixteen [1932], he graduated high school and moved to Israel. While he was there, he helped found a kibbutz. Like all Jewish families, [his] said, “That’s fine, but you have to go to college.” So, he had to come back. It was Palestine. It wasn’t Israel then, and they had no universities. So he came back. He imagined he wanted to become a farmer and study farming, so he went to Cornell and got his Bachelors degree, and then went to Wisconsin to get his Ph.D.

While he was there, we met and we fell in love. Instantly . . . like instant coffee. At that time, I noticed he did a lot of drawing. If he went anywhere, he drew. If he talked to somebody, he drew their picture. He had a sketchbook with him all the time. I thought, “That’s funny. That’s a funny kind of farmer who likes art.” I took him to visit Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin. As soon as he walked into that drafting room he said, “This is what I want to do.” So instead of getting his Ph.D., he immediately relocated to Harvard.

I had to finish my degree, so we were separated for almost a year while I finished up at Wisconsin. That was after the Nazi regime, so all the avant-garde artists had to escape, which they did. Walter Gropius, who was Director of the Bauhaus, became the Director of the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

What luck! Can you imagine the luck Larry and I have had? First in meeting each other, because we influenced each other. And secondly, going to Bauhaus, where he met a group of people, who helped him nd a direction where he could go with his ideas. He graduated Harvard, and his colleagues were people like Phillip Johnson and I. M. Pei, all the people who have become very famous, and who have become acknowledged for their original thinking.

It’s interesting that you had this experience with your husband, and at the same time Josef Albers [from the Bauhaus] went to Black Mountain College and started influencing people in the Bauhaus philosophy, which melded art and life to an extent that hadn’t been seen before. Did you know Albers?

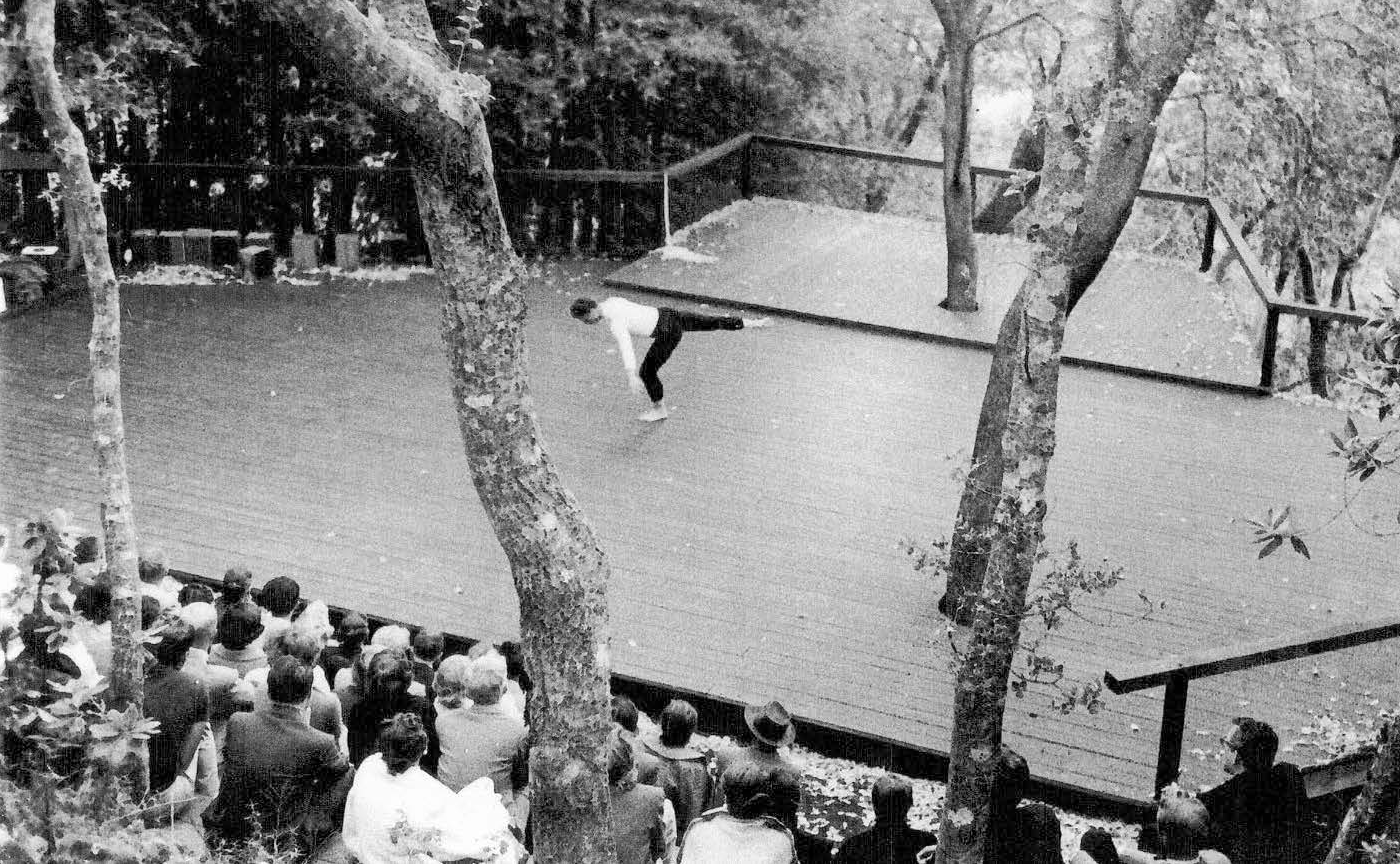

I knew all the people from Black Mountain. They went in one direction, and Larry and I went in another. Where their art became conceptual, our art became organic and nature oriented. We were very good friends. John Cage and Merce used to come here and live with us, while he was doing his concerts.

We were very good friends, and because we were such good friends, I understood our differences. If I had lived in New York, perhaps I would have become a conceptual artist, but I have an outdoor studio that is anything but a box. I am surrounded by trees and birds and the wind and the sun and the rain. I danced in the rain. It obviously has to influence you. It gives you a different point of view about reality.

Let me read to you something Larry wrote about dancing outside in all the different spaces he created: “My intention in designing this space is to create a magical space, where each person can find their spiritual connection to nature and all its being.” I’ve been so lucky to dance all these years on the dance deck he designed for me—it’s given me so much access to so much of the natural world and has influenced me so profoundly.

Merce Cunningham on the Dance Deck. 1960. Photographer Unknown. Courtesy of Anna Halprin.

I did a piece that I dedicated to Larry shortly before he died, at Stern’s Grove in San Francisco. As we worked on the piece, Larry would say, “I want to go down and see what you’re doing.” I said, “Larry, we’re not ready.” He said, “but I want to come anyway.” So he came and we weren’t ready. We were still in an exploratory mode, but the dancers were so excited that he was there.

They gathered all around him to hear his feedback. And so he said, “That was horrible.” I kept poking him to be quiet, not to say that. But he looked at me and said, “Well, but it is. They don’t understand anything about architecture!”

So, we went back to work, and I realized that we had done enough exploration, and I needed a template—a boney architecture. All we had was responses, but it wasn’t connected to any structural element. I suddenly got this image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. I said, “Why can’t I use that?”

I took the Vitruvian Man and organized it spatially. It has two diagonals—the legs open—and another diagonal that way [arms open].Where the two diagonals cross is the center, and then he had a shadow figure vertically up and down, and a circle saying it’s all connected. So, I used that as a template. The composition of the dance was especially for Larry. I told him that this was the architecture that the work was based on. When we finished, and he saw it, he was so pleased. He sat in the rain with an umbrella, and it was the last thing he saw that I did that was dedicated to him.

Task Orientation—The Evolution of Dance to Include Every Movement.

JH: I’m interested in your task-orientated process, which merged art with everyday actions.

AH: I was looking for a way to approach movement, which was free of the stylistic approach of Modern Dance. This was what I objected to that summer when I witnessed people dancing like Martha Graham or Doris Humphrey. I was more interested in how people moved individually, rather than stylistically. But then, I went further than that. It wasn’t enough to just take a log, carry it, and put it over here. It had to be a sensorial experience and that had to be communicated by the dancer.

These tasks were a physical experience, and there were different ways that you could explore an experience using time, force and space.You could carry it [the log], but you could carry it fast. You could carry it slow. You could carry it with two people.You could carry it on your head. In other words, I had a very disciplined way of working with tasks that gave the dancer an opportunity to explore a lot of movement options.

It wasn’t enough just to take your clothes off. So what? It was how you took your clothes off. We did it very slow motion. We did it with an awareness of the sculptural effect of the movement. I was very careful to bring art processes to all the movement tasks we did.

Task oriented movement became very misunderstood on the East Coast. Even Yvonne [Rainer], and Simone [Forti] and Trish Brown, and the other dancers who started the Judson Theatre, they just got involved in the task as a task rather than as a movement experiment or exploration. But Simone was with me for seven years, so she got a little bit more into it. I just used it as a jumping-off point. They used it as a concept. To this day, there’s this difference between us.

A jumping-off point to where?

For an art experience. For how you could turn, what I called ordinary movement into dance by using the principles of art. All movement takes place in time through space with force. I would use those elements to shape the movement. The task of removing your clothes becomes a beautiful art experience, with meaning. It goes beyond the action itself into a different realm altogether.

When I am using nudity, I want you to see my body as part of nature. My body is nature. You don’t see trees with clothes on. This is nature. This is part of nature. So I don’t wear clothes. If I’m going to work without clothes, I’m going to incorporate the environment in what I’m doing. The immediate environment is the clothes themselves, and how the clothes themselves change the way you see the form of the body.

I was working with nudity, not from the point of view of, “Oh, this is shocking,” but because I came from this more organic, art-related vantage point. I was shocked when we were arrested for nudity in New York in the Sixties. “Why are you arresting us? You see nudity in galleries all the time. Why are you arresting me? I’m not doing anything wrong.”

This is “Parades and Changes?”

Yeah. I was arrested in New York for doing “Parades and Changes” for the nudity.

And now a French group has taken “Parades and Changes” and revived it. They got a Bessie [New York Dance and Performance Award] for it! But when I did it in 1967, I was blacklisted for fifteen years. I couldn’t get engagements anywhere. Isn’t that interesting? And now, forty years later, awards. . . .

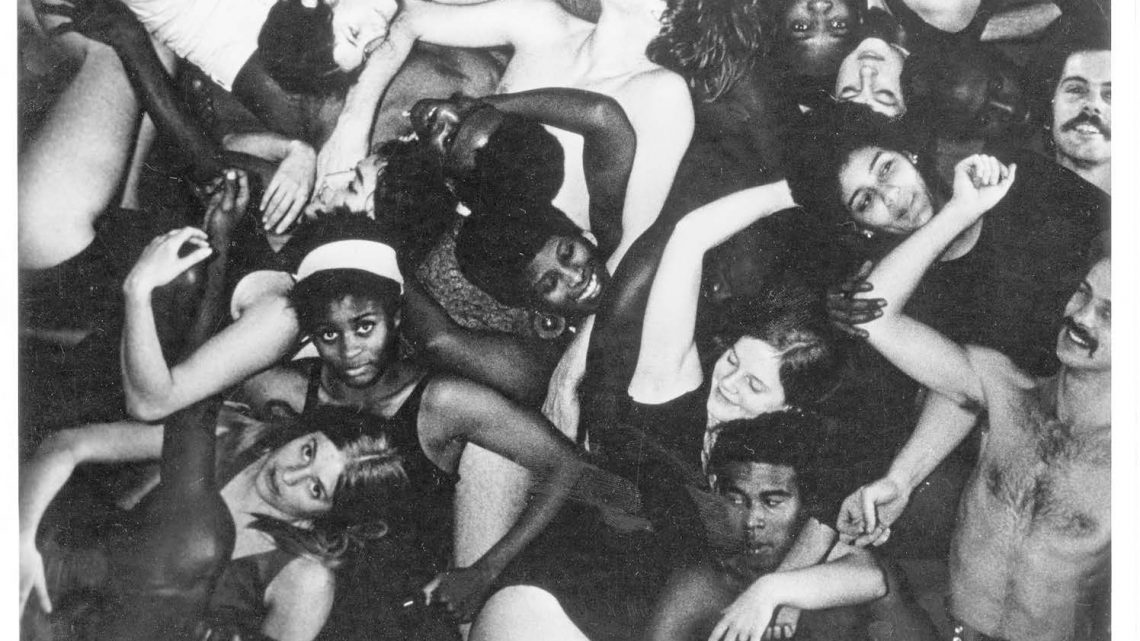

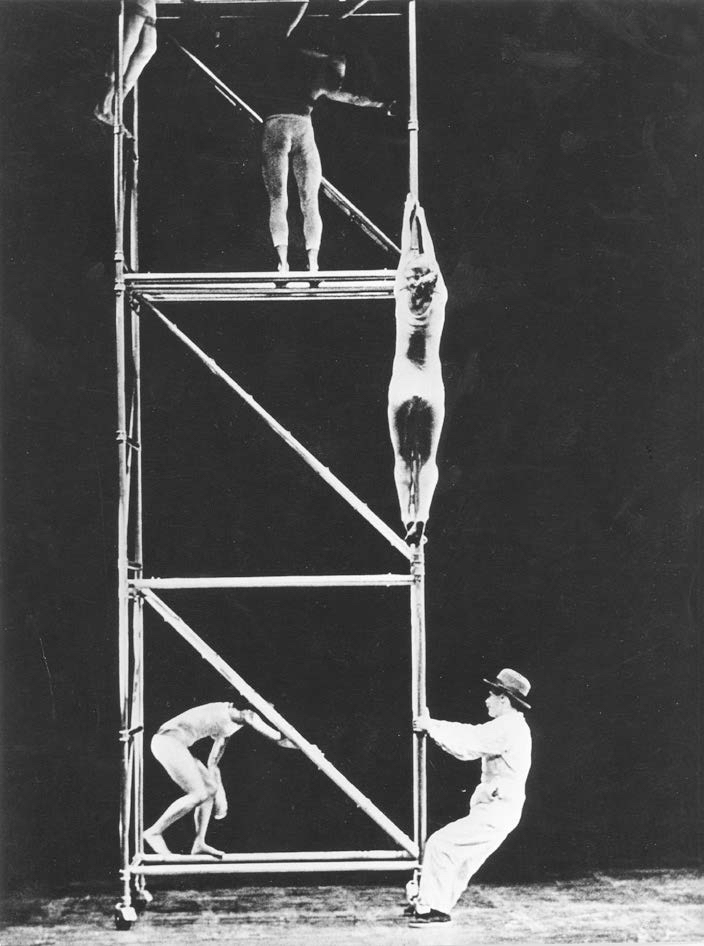

Anna Halprin and Dancers Workshop of San Francisco, Parades and Changes, Sweden, 1965. Photograph by Ove Ohlstrom. Courtesy of Anna Halprin.

Isn’t this the way of all avant-garde artists? It takes thirty, forty, fifty years. . . .

. . . to catch up.

Do you think there is a relationship between your task orientated dance, art as life, with Duchamp’s Readymades?

The urinal in a museum. We called it Found Art.

Like a telephone book made into poetry.

It was happening in all the arts. For John Cage, every sound you hear is valid as music. For dancers, every movement you do is valid as dance. It was a way of unmaking so many assumptions about what art is.

Do you remember the famous art scene between modern dancer Jean Erdman, Joseph Campbell’s wife, and Morton Feldman? I love this story.

He brought her into court, because she commissioned him to do a piece. She didn’t want to pay him for all the silences! There were a lot of silences. You remember—silence is sound. And he said, no, she has to pay for that, because it’s part of the music. It was brought into a court. Can you imagine the judge trying to figure this one out? How is he going to figure this one out?

Jean Erdman and Joseph Campbell were very involved in the arts and had a relationship with John Cage.

The difference is that Jean Erdman was always a modern dancer. She used music like Feldman and people like that, but she was still a Martha Graham dancer and a Conceptual Artist. She was looking for new ways, but it was still based on modern dance. She didn’t use task-orientated movement.

I’ve never been interviewed in the kitchen before. Everybody’s wanting to interview me these days. I don’t like the interviews, because . . . they’re not interesting.

I’ve read several interviews you’ve given over the years, and they’ve always been interesting . . . and informative.

You’re the first one to interview me in this particular way.

I consider that a triumph. [laughs]

It is a triumph [laughs], from my point of view as well.

Audience Participation—Widening the Field of the Dance

JH: Can we talk a bit about your relationship to the audience? I think that’s important.

AH: It is. Let me go back a little bit and tell you another story. I didn’t want to be away from my two children while they were growing up. I gave up my studio in San Francisco, and Larry designed a place for me here.

It was a dance deck. I didn’t have an indoor studio, just this outdoor deck. It wasn’t a rectangle, like an ordinary studio. Suddenly, I didn’t know where center was. I didn’t know front or back, or side-to-side. It was just like nature.

It took me into nature. It took me into relating to the trees the same way I might relate to a person.When we started doing experimental presentations, I realized that the audience was part of the dance. They’re right there. They’re in my face. I’m in their face. So, audience inclu- sion was really an extension of the environment for me.

And then, because people weren’t trees, because they were humans, and they had thoughts and feeling and capacities to respond, I began to use that. That became very important, especially at the point that people began throwing things at us. People began walking out. People became enraged, and I thought, “I don’t know what I’m doing to make people so upset.” I’m just minding my own business, and innocently doing what seemed perfectly natural to me.

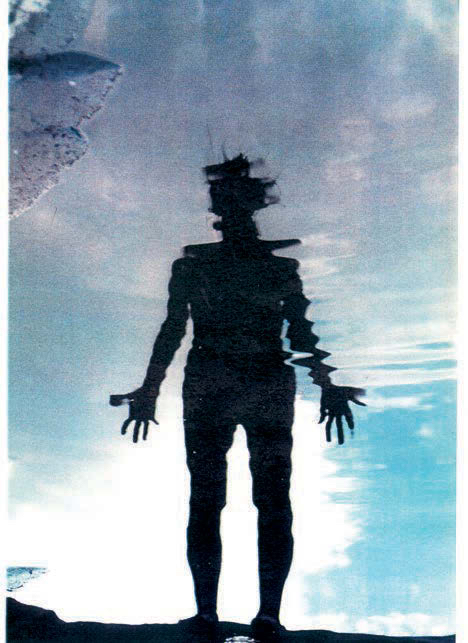

Anna Halprin, Still Dance. Photo by Eeo Stubblefield. Courtesy of Anna Halprin.

Then, I began to develop scores or tasks for the audiences. And I watched them do these tasks. What did they do when they were given a score to work with? The inclusion of the audience into my work was another dimension. The audience members weren’t just mute spectators. Not mute like a tree or a rock. I began to recognize, “They have feelings. They have ideas. I already knew they had responses, but I wondered how I could include that in my work? It’s not that they are just objects in space, they’re real people with real human responses. So, I began to do things like giving them a mask, or having a role to play.

Duchamp said that the spectator completes the artwork.

How did that change his process of creation? See, that became another element to deal with. If in fact that’s true, which I believe it is, how do you incorporate their response, and how does it form and reform your individual expression? I was searching for an answer to that question, which is why I did the audience participation scores.

I wanted to know more about how audiences work. How they came together, or how they separated. I did female and male scores—what’s going on there? I began to use this in my development, when I did a piece like, Ceremony of Us, which was a struggle. The intention of the dance was reconciliation between white people and black people. It was right after the Watts Riots. That was very real. How could we engage ourselves in an art process and create something that would also address our, in this case, political intention?

What is so beautiful about the Ceremony of Us, is that originally the sponsors just wanted you to do a performance, and you said, “No, I want to engage these people and give them the full experience.” I think this is your contribution—dealing with the audience.

I believe art is an alchemical relationship between the artist and the object, and that the true purpose of the artist is to transform him or herself. It seems that you’ve gone beyond that. Not only have you transformed the artist, but the audience as well, and that is a major contribution.

Thank you. But also, if I have the sensitivity and intelligence to incorporate audiences from a lot of experience in working with them, it’s a process that affects the dance as the dance is being created. For example, for the Watts project, when the audience arrived at the Mark Taper Theater [Los Angeles]. . . .

[A timer goes off indicating that something needs tending in the kitchen. Halprin addresses her assistant.]

Do you mind going up, looking in the oven and making sure my granola is not burning, stir it up a little? Put this in the interview, this facet of the artist being a homemaker, the grandmother, all that multi-faceted. . . .

So, when the audience arrived at Mark Taper, we had been working together separately. The black dancers were working in Watts, separately from the white dancers who were people I invited to be in the dance.

I would go down to Watts every week. I developed a score based on what happened the week before. I gave the same score to the black dancers that I gave to the white dancers. I wanted to exaggerate the differences. And then, we put the two groups of dancers together for ten days. We lived together communally. And we developed the score—communally. We hadn’t developed the RSVP Cycle process yet, but simply using whatever responses they had to the scores was a resource for developing this art piece.

Now, how did we extend that into the audience? There were two entrances into the auditorium at the Mark Taper. All the black dancers were in a processional lineup on one entrance, and all the white dancers were in a processional lineup creating a passageway for the audience on the other side.

When the audience arrives, they have to make a choice. “Am I going to go with the black group, or am I going to go with the white group?” And the dancers were greeting them with, “When I look at you, this is what I see. This is what I imagine. This is what I’d like to see.”

Well, there was a totally different response from the different groups. The black audience members really got into it. “Oh honey, you see this, and you see that, and this is what I want. I want some money.” And the white people would come in and just stiffen up and were totally embarrassed by the whole thing. The audience now has all black people on one side of the auditorium, and all the white people on the other. They immediately felt what we were going through.

When we came in, we came in on conga lines—the black group separate from the white group. They started responding to each other, and they saw the dance evolve. At the end of the dance, everybody went out into the plaza, and all the musicians started playing and they formed processional lines picking up the black and white dancers and intermingling them.

So, they ended up in the plaza dancing together. Isn’t that interesting? What I want to get across was not that I am using the audience, but that they are incorporated as part of the experience. It’s a different attitude, a different way of working. It changed me forever.

Current Work

AH: This year I’ve been working on a Trilogy in memory of Lawrence. Stern Grove was one of them. He was alive for that. He died before he got a chance to see the second one, which was called, In the Fever of Love. The subtitle was from the Song of Songs. Here is an example again—it’s a love story—how do I deal with that?

I found a group of erotic drawings I had never seen that he did while he was on the destroyer [USS Morris VII] during World War II. I had never seen them, because he was on his way to Okinawa, and he had been drawing. He drew all the time. He decided he would roll up all the drawing he had done, and he communicated with a sister ship that was going back to San Francisco, and he pitched the drawings over to that ship. He said, “When you go by, I’m gonna try to pitch this package, and send them to my wife.”

He pitched it over. He had no idea if they made it or not. I never knew anything about it. Actually, the ship was hit by a kamikaze. He was obviously fortunate enough not to be killed. Those were a whole series of erotic drawings, which I didn’t see until after he died.

They were sent to New York, but I wasn’t there. I had gone back to Chicago to be with my family. The drawings stayed in New York until his parents died, and then they were sent to his office. When I found them after he died, I thought this is what I’ll do to bring Larry into this dance. I’ll base the dance on those drawings. I’ll base the dance on those drawings. And we started the dance from the postures in those drawings.

I got two of the best dancers who could do this, and that was Shinichi [Momo Iova-Koga] and Dana [Iova-Kova]. And then I got a narrator, a good friend of ours, who worked with Larry a lot, and he became a narrator. Then I got my grandson, who’s a poet. I used family members, and the audience all brought lilies. So, when they were seated, it was just a bank of lilies. I did this because in his memorial I said, “Where have you gone my beloved, where are you?” and he said, “I’ve gone to my garden to collect lilies.” And I said, “I’ll come and I’ll join you.”

And so, that image that came from Larry, not from me, was what I used. I did a sensory walk with the audience as they came down the stairs. They placed the lilies. I did a walk with them through the woods, and then we came up and had a reception and all kinds of foods from the Song of Songs.

I tried to bring Larry to life with his own material, and tried to find a way to meld it all together. It was a very personal intimate experience. I wouldn’t even say it was a performance. Maybe it was a ritual. Maybe it was a poem. So, that’s another thing. Breaking down the barriers between art and ritual—what is a dance performance?

Who are you doing this for? Why are you doing it? And what difference will it make in anybody’s life? When you start asking those questions, it leads you to a different process.

I was devoting my life to this work. Why was I doing it? Can I do something more useful in the world? That really put a twist on the emphasis of why am I dancing, who am I dancing with, and what difference is it going to make?

I’m ninety-one now. The older I get, the more questions I have. The more I demand of myself. How lucky I’ve been to have the space and time and wonderful comrades throughout my life with whom to ask these kinds of questions.

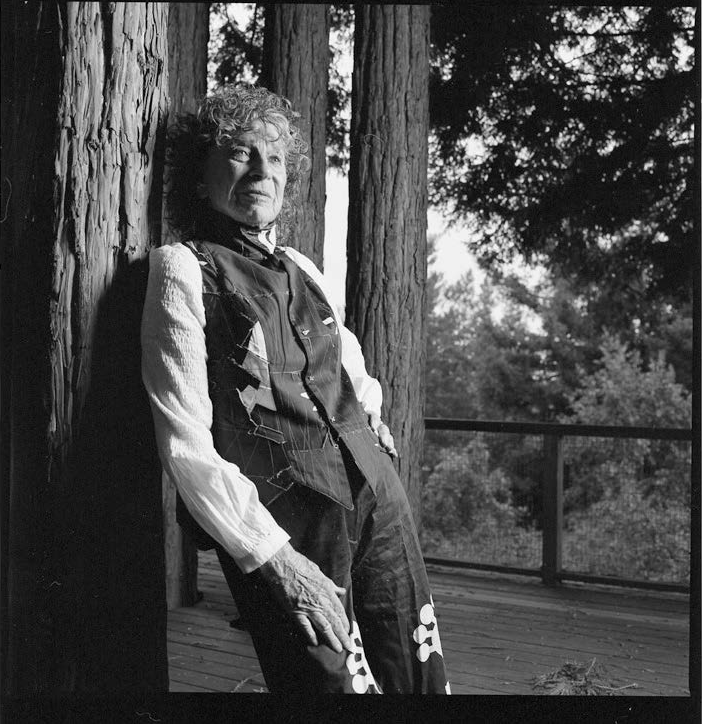

Anna Halprin, 2012. Photographed at her home by Andrew McClintock.