THE PLIGHT OF P

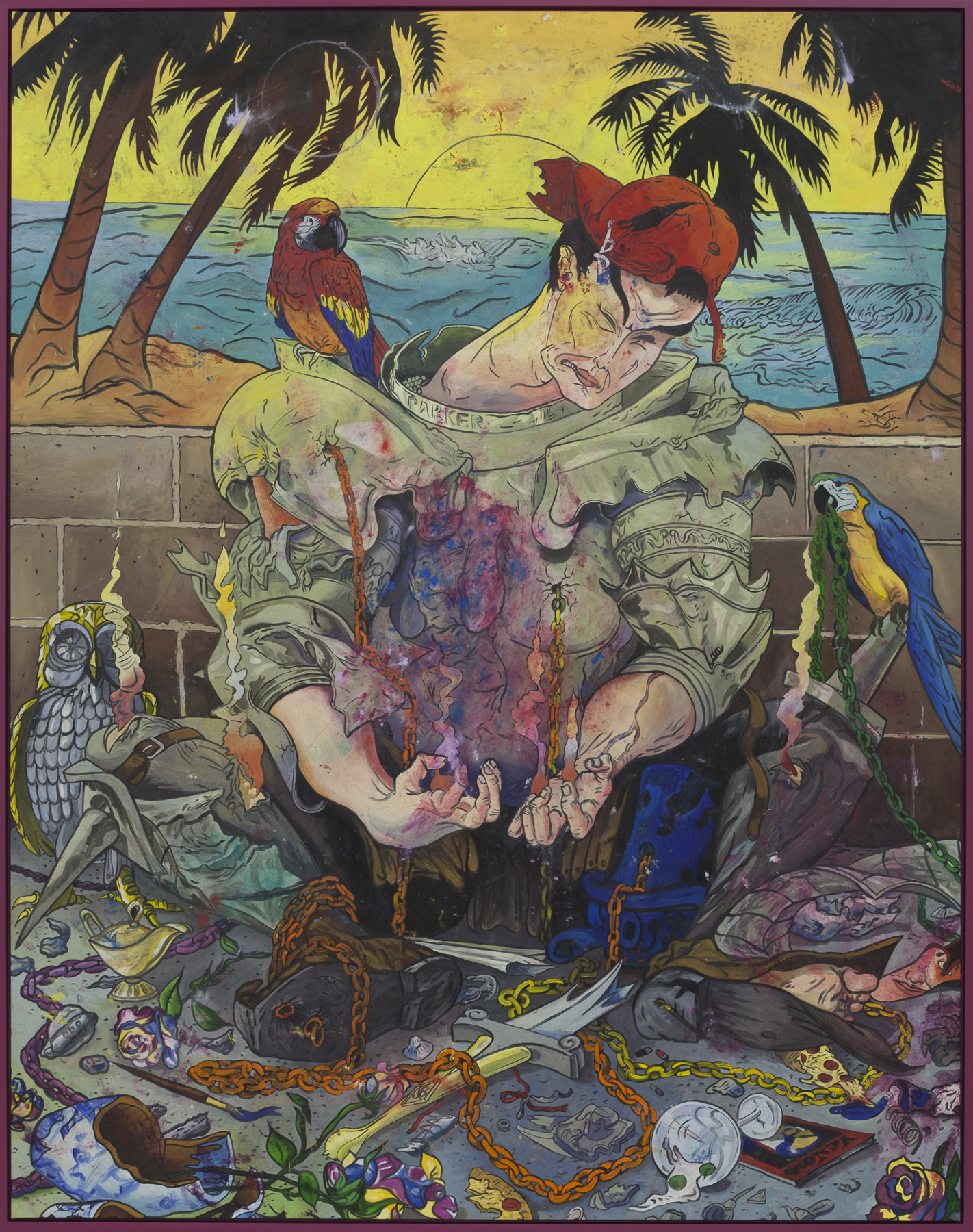

Where to begin? I suppose with the fact that Parker Ito is currently not doing interviews. Those who’ve followed his practice (and perhaps even those who haven’t) might interpret this as a somewhat surprising turn. After all, young Ito never shied away from provocative declarations broadcast across an array of platforms and through a number of highly stylized personas. Some of these guises eventually became formalized as visual motif, joining the other surrogates, doubles, stand-ins, and refracted self-reflections (physical, artistic, allegorical, and otherwise) that densely populate his work. My favorite incarnation remains the knightly Parker Cheeto, overseen by attendant parrots, seemingly exhausted by the Sisyphean task of envisioning an exhibition so unwieldy it had to colonize multiple spaces across cities and continents—or at least, that is how the artist conceptualized his total output from 2014 to 2015.

Tackled as discrete shows, this year-long undertaking also conjured various artistic roles: the Sunday painter whose amateurish still-lifes had their first taste of the sun in the neighborhood coffee shop in Prelude: Cheeto Returns (Rainbow Roses Still Lifes at Kaldi Coffee and Tea); the art student willfully hijacking the typically unused spaces of an Echo Park gallery, in Part 1: Parker Cheeto’s Infinite Haunted Hobo Playlist (A Dream to Some, a Nightmare to Others); and a blue chip ingénue pushing the limits of the white cube with increasingly fastidious demands, in Part 2: Maid in Heaven/ En Plein Air in Hell (My Beautiful Dark and Twisted Cheeto Problem). I would add to this a slew of other self-declensions, perhaps most notably the studio ringleader/chronic collaborator, who at times took the lead in creative decisions, while at others was happy to recede into the din of production. I have tried to keep track of this colorful cast, but invariably they seep into one another, lost in the overgrowth of LED lights and iridescent surfaces that framed the fullest articulation of the project, Part 3: A Lil’ Taste of Cheeto in the Night, presented in a warehouse on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles.

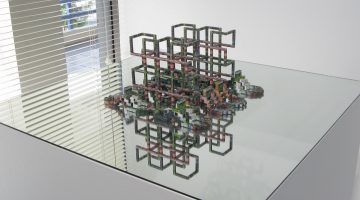

Installation view, A Lil’ Taste of Cheeto in the Night at Château Shatto, Los Angeles, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Château Shatto.

A Lil Taste of Cheeto in the Night (En Plein Air Decision Fatigue), 2013-2015. Oil on canvas, acrylic on aluminum strainers, artist frame, and hanging hardware, 122 x 96 x 2.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Over time, these shifting guises have provided both the crux and pitfall for a practice that exists through its own proliferation, leaving in its wake a series of objects—some of which could be qualified under the rubric of art, others more slippery in their becoming. Is this the byproduct of the Internet? Who’s to say— but one would be amiss for not crediting the Web’s elasticity for facilitating Parker’s beginnings. Take, for instance, paintfx.biz (2010–2011) a loose online collective/club/company organized with like-minded peers Jon Rafman, Micah Schippa, Tabor Robak, and John Transue, who he met through social media. Using various graphics and painting softwares, they embarked on a game of digital exquisite corpse, building an archive of simulated painterly gestures that could be accessed as easily as Photoshop filters. There is much to be extracted from this protean exercise, particularly as it pertains to the shifting role of the computer screen. For me, it foregrounds the redefinition of “interface” from a point of contact with technology to a conduit onto other unique users. Here, the artist emerges as de facto collaborator, operating in a field where they are in a constant feedback loop with many equivalents. Ito embraced these conditions from the onset, testing out its manifold possibilities through the Paint FX output as well as the repeated outings with Aventa Garden—another loose configuration that’s also maybe a band (I was never really sure) with the artist duo Body by Body, comprised of Cameron Soren and Melissa Sachs. In this configuration, Ito/Cheeto becomes Deke2, the drummer.

Installation view, Eastern District Savings Bank, Aventa Garden (Body by Body + Parker Ito), Paris, 2016. Courtesy of the artists and LAPAIX.

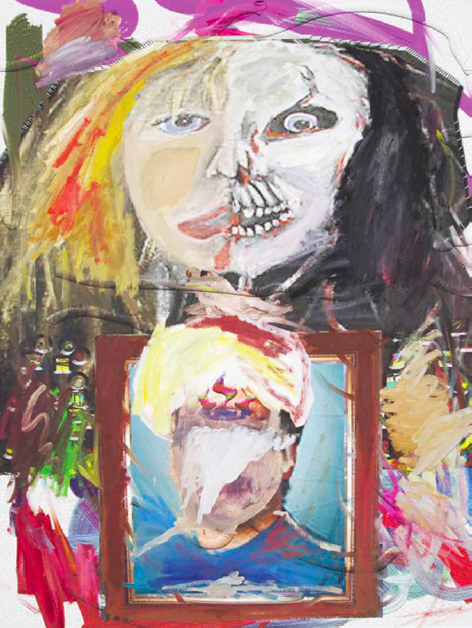

Deke 2, Mortality, 2010. Oil on digital print on canvas, 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Can’t keep track of the shuffle? I suspect that is largely the point. After all, the importance of these personas is not necessarily their family resemblance, but the position they outline: namely, the artist as profile, individuated by so many surface effects. Art historians will quickly point out this is far from a novel concept (insert your own favorite example here), but what remains prescient is how the Ito-Cheeto-Deke2 compound re-contextualizes questions of replication and authenticity within a set of historically specific conditions. Thus, the Internet rears its ugly head once again, but perhaps from a more nuanced vantage point where, in order to grasp its macro effects, one must contend with its micro-reconfigurations, specifically across questions of liquidity, asset building, and branding.

Installation view, Parker Cheeto: The Net Artist (America Online Made Me Hardcore) at IMO Gallery, Copenhagen, 2013. Courtesy of the artist and IMO Gallery.

These issues are tackled explicitly in the series, The Most Infamous Girl in the History of the Internet,* (2010–2013), or “Parked Domain Girl” for short. Developed as painterly memes, these works elaborate on the same, nondescript portrait of a female student wearing a backpack that was used by a parked domain company as a placeholder for unsold websites. The ubiquity of the image, combined with the exchanges and transactions she both elides and embodies, provided the starting point for open-ended variations that call attention to shifting models of artistic production, authorial intent, and the divorcing of personal images from their original referents. Ito is complicit in all of this, exploiting the meme as much as he unravels it, unearthing its backend history along the way. It turns out the mystery girl is the photographer’s sister, enlisted for an impromptu shoot to test out a new camera and unwittingly ending up as a freely-circulating caricature. The strong undercurrent of fetishism is evident in Parked Domain Girl’s repeated usages—but it also applies to Ito himself, who advances this process even as he collapses into it. In the end it is difficult to draw clear distinctions and he becomes her stand-in (rather than the other way around): a Net-y nymphet unwittingly circulating as a placeholder for unspecified value.

This conflation might be clearest in Parker Ito’s contentious relationship to the art market. Boasted as its champion or derided as a harbinger of its collapse, Parker has remained tethered to its ebb and flow in most critical discussions of his work. Granted, this is far from incidental, as his production model willfully undermines (or at least fucks with) the market’s standing currencies: deliberately hyper-producing, refusing to subscribe to the usual signs of authenticity (like signatures), or exploding them to monumental proportions until they too become another visual motif. It’s a tricky gamble, one whose stakes are raised by freely trafficking in editions and multiples, or by piling on the branded swag, including baseball hats, towels, amateur pottery, and other such marginalia that disrupts the sanctimonious space of painting. “I wish I could make a reflector painting for every person that ever asked me for one” was a favorite mantra regarding a particularly sought-after series. Followed to its logical conclusion, this certainly fueled consumption, but only at the risk of burning itself out.

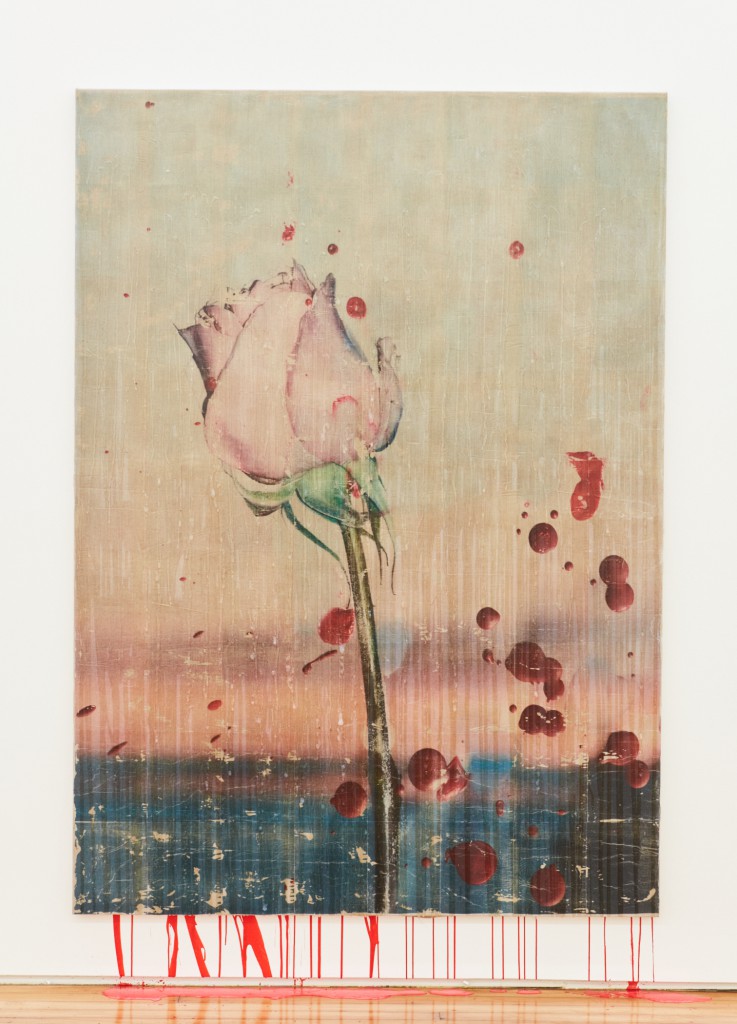

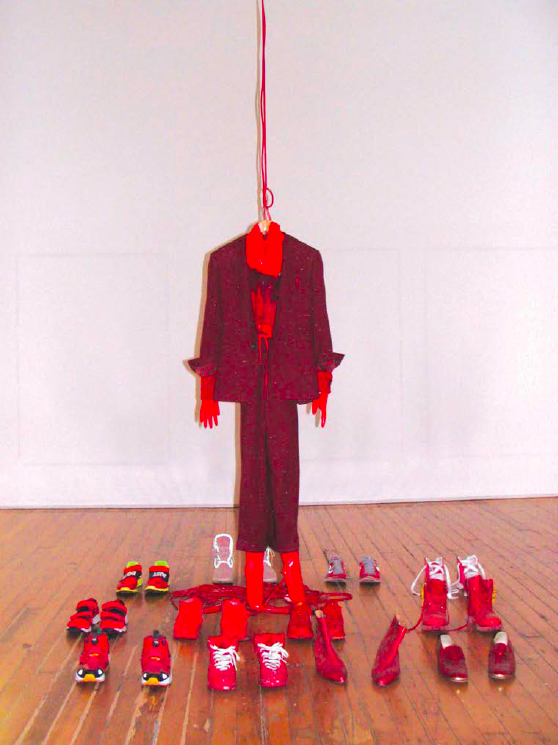

Perhaps this aftermath is one way of approaching the latest exhibit, live from capital records, b.—i am not a human being I am a disgusting piece of shit at Château Shatto in Los Angeles. Deployed in six installments, the show has a general tone of evacuation, a ceremonial cleaning of the cache. First, there a series of piecemeal floral still lifes installed over Polaroids (the eclipsed snaps remnants of a long forgotten exercise recently rediscovered in the shuffle between studios). This gives way to other distilled gestures: a video, a tinted window, and a lonesome stainless steel sculpture, all of which materialized unexpectedly if only to announce their ghostly exit. For me, the most telling is Suit (2016), the second installment of the series, consisting of a sculpture made from a bespoke suit recently commissioned by the artist. Despite many fastidious fittings and custom touches it somehow never felt quite right, but it found a second life relegated to a hanger, suspended from a power cord, and filled with a latex bodysuit, the deflated outline where a body would be. On the floor below: an amassing of red shoes gathered over the last 10 years, each displaying various signs of wear. Some, like a prized pair of cardinal Adidas, activate a rush of tender memories for me, while a pair of maroon Chelsea boots strike me as curiously mute, standing in stark contradiction to the imagos I hold dear.

Installation view, live from the capitol records b.– i am not a human i am a disgusting piece of shit at Château Shatto, Los Angeles, 2016. Courtesy of the artist and Château Shatto.

February 26th, 2016 (Olivia’s rose), 2016. Acrylic, toner, and gloss varnish on linen, 84 x 60 inches. Courtesy

of the artist and Château Shatto.

Suit, 2016. Wool, latex, cotton, zipper, wood, nylon, digital print on silk, hanger, Sharpie, power cord, and artist’s

shoes accumulated over a 10-year period, dimensions variable. Photograph by the artist. Courtesy of the artist.

It might be tempting to read Suit as an act of contrition, or at least a relinquishing of the hazy fictions spun around a creamy dreamy center. But that endpoint strikes me as suspiciously resolute, as do the outward signs of its own authenticity. In a strange way, the encounter brings to mind an online interview with Jason Rhoades I once read. In it, he attempted to articulate the sensorial urgency of his installations: “I think people should be overwhelmed. I think it should shut you down; it should make you give up something.” Rhoades never makes the nature of that “something” particularly clear, but it occurs to me that at this moment Parker would have plenty to choose from.

*All texts and images considering The Most Infamous Girl in the History of the Internet have been deleted from the artist’s website since 2014. Any subsequent texts or images referring to the project that occur are against the artist’s wishes.