Style Wars aims to appreciate how critical considerations of style can offer an opportunity to think across subjectivities and cultural practices that are often disassociated or pitted against one another. In light of recent calls to address how dangerously toxic certain forms of masculinity have become,1 this edition of Style Wars explores how the aesthetics of mending—and, in particular, the aesthetics of mending those things that seem beyond repair—may provide a chance to consider why masculinity is so regularly fashioned vis-à-vis acts of violence and wounding, and how this arrangement might be styled otherwise.

“I wonder if a soldier ever does mend a bullet hole in his coat?”— Clara Barton, US Civil War Nurse and founder of the Red Cross

If you have been to London, you have probably been to Trafalgar Square to meet Admiral Horatio Nelson, a military martyr who stands some 170 feet up in the air, regally surmounting a classical column that is guarded by four monumental bronze lions. With his head cocked slightly downward, Nelson appears staunch and irreproachable.2 He looks out across the city’s expanse, while simultaneously surveying the crowds that pool beneath his feet, forever judging whether or not these masses are worthy of his singular sacrifice. Of course, nothing draws contempt more sharply than a figure who appears beyond reproach, and nothing can damage the character of such a virile figure more than an injury to his masculinity—particularly an injury begot by the simple suggestion of a markedly feminine conceit.

Stand below Nelson’s column long enough, and you’ll hear the rumors that have been churning for the last two centuries: “Yes, he died during battle—but his death was owed to his own vanity! Despite warnings, he insisted on always wearing his navy blue undress coat with all of its conspicuous decorations. Placed upon his chest, the glittering insignia made it easy for the enemy sharpshooters to line-up the perfect shot straight through his heart!”3 A literal fashion victim, this hero is brought down to earth on account of what some might consider a commitment to style over country: a knowingly sordid image of a man who is said to have lead the British Navy into battle with the now legendary rallying cry, “England expects that every man will do his duty.” England expects, in other words, that “every man” will put himself on the line, and earn his masculinity via rituals, narratives, and professions that are predicated on brutality—and that he will do this without grievance, or hesitation.

To be a man under such conditions, is to enter into a deeply gendered dialectic forged through acts of wounding and care that demand “men” to hurt, and “women” to do the work of mending.4 The “man of vanity,” or the dandy who dares to tend to his body, complicates the way modern gender binaries synthesize sexual difference. To insinuate that Nelson, a picture of masculinity, dared to care for his dress is to make his lionhearted image dubious. It suggests that he stopped to think and prepare himself for war, and that he didn’t just innately perform his duties—it implies that he considered war’s pomp and its circumstance, that he knew his duty was something constructed, and not simply natural. Nelson, the dandy Admiral, blurs the very lines that work to separate the sexes and to channel the violence that modern systems of power are built to capitalize upon.

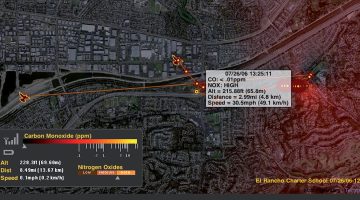

Navy-blue Vice-Admiral’s undress coat worn by Horatio Nelson when he was fatally wounded at the Battle of Trafalgar on October 21, 1805. Collection of the National Maritime Museum. Courtesy of the Internet.

On the second floor of London’s National Maritime Museum, a humble vitrine is tasked with the remarkable duty of preserving the actual coat that Nelson wore during his final battle. Within this climate controlled bubble, the “Trafalgar coat” survives to tell many stories. Its small size surprises those who expect their war heroes to have a “larger than life” stature. The coat’s right sleeve is designed to button directly onto its left lapel in order to accommodate a battle wound that Nelson suffered eight years before his death, an injury that claimed much of his right arm and powerfully attests to Nelson’s unabated commitment to perform what “England expects” at great cost.5 The coat also features the conspicuous ornaments of legend—each earned as a result of the Admiral’s exemplary service to country, and each boldly embroidered onto the coat’s front. Most importantly, and just above the coat’s uppermost starburst, a rather ominous badge of honor appears: a clear-cut hole on top of the left shoulder, narrowly below the epaulette. Historians attest that this hole corroborates eyewitness reports of Nelson’s demise. It marks precisely where the fatal bullet entered Nelson’s body before it ripped through his spine and eventually claimed his life. In contradiction to the gossip, this small hole does not correspond with the placement of his coat’s more effete embellishments. Instead, it bears witness to the fact that Nelson’s masculinity was not a casualty of his wounding, but that it was secured through it. Or, that Nelson died a soldier’s, and not a dandy’s, death—as if these identities were utterly incommensurate.

It’s rare for such a relic to endure the centuries. The coat’s wool and silk fabrics are incredibly volatile; their preservation requires an extensive amount of technical and affective, emotional labor, along with elaborate fiscal resources. Nelson’s Trafalgar uniform evidences centuries of mending and conservation that are all unironically aimed at preserving that which is effectively beyond repair—the occurrence of a decisive hole. This, all so the image of Nelson’s masculinity might be maintained, intact, and in spite of the fact that many people have long worked to question this image through their maintenance of a particular form of gossip. As such, this coat can be said to attest to a cultural need (or a national will, even) to materially substantiate the distance that lies between proper and improper forms of masculinity, particularly in respect to the routine and spectacular acts of wounding that these gender identities presuppose. At the same time, this coat also attests to a critical will to disavow such a construction—and to desire different forms of masculinity. After all, if not for the rumors, there would be no need to do the extensive work of maintaining this sartorial relic in the first place.

Here, the whole business of state violence is revealed to require accepting the notion that our identities are forged through obligatory acts of barbarism, and that the only way to manage this chaos is to assume one of two positions. Despite the obvious tenuousness of this arrangement, many of our personal experiences attest to how we each work to fix these identities, consciously or not: how we each do our duty to uphold the two-fold order of things, regardless of the gnawing sense that things can (and ought) to be otherwise. Presumably, this is owed to the fear that the social fabric will, itself, dissolve if “men” do not work to harness this powerfully primal violence through their bodies, and “women” do not struggle to deal with its aftermath.

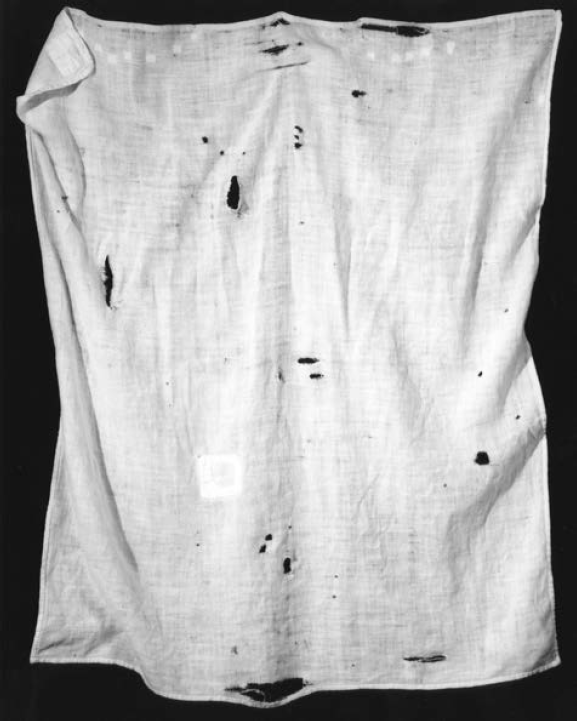

Few images encapsulate the complexity of this scenario better than J. John Priola’s 1995 photograph Dish Towel. Part of a larger series of photographs entitled Saved, Dish Towel’s worn topography is a testament to our repeated obligations to make ourselves susceptible, and to do the maintenance work that modernity requires of us each of us.6 The single patch, apparent in the towel’s bottom-left quadrant, is a complex figuration of gendered social relations. If presumed to be recent—the patch appears as the first of many acts of mending, the start of making this holey relic whole again. The rips and tears in this fabric are, thus, seen as an invitation to enter into a specific kind of social relation, and Dish Towel can be read as being emblematic of how and why the gender binary is imperative. On the other hand, if one regards the patch as predating the repeated cuts and blows that are scattered across the textile’s expanse, then Dish Towel must be read as a way of styling the futility of such an arrangement. It marks the limits of this kind of care and it suggests that the kinds of violence that underwrite “properly” structured masculinity can only produce irreparable damage. As with Nelson’s coat, Dish Towel harbors a critical claim, questioning the construction of a social fabric that is organized around holes that tear us apart. It suggests that this kind of social organization forces us to submit to relentless and futile acts of tearing and repairing.

J. John Priola, Dish Towel, 1995. Gelatin silver print, 24 x 20 inches. framed. © J. John Priola, all rights reserved. Courtesy of the artist.

What becomes clear are that some things are, indeed, beyond repair. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t tend to them, but that we ought not to pretend that they can be fixed, or that the violence can be undone. We need to imagine how to restyle the relation between wounding and care so we can start to transform the fabric of our society.7 Here, the work of the artist Mark Newport comes into view—and in particular a recent series dedicated to critically deconstructing the work of mending. As Newport explains, the series was borne out of a flash of recognition that he experienced while folding and caring for his own son’s clothes:

[T]he holes in the knees of his pants remind me of my childhood exploits, the falls that punctuated each adventure and the scars I carry from those accidents. My body and most often the knees of my pants would be repaired the same way: wash then patch (an iron-on patch for the pants and a Band-Aid for me). When things were more serious, stitches might be required for the body and the clothes would be discarded. Even then, darning and suturing leave a mark, a scar. Each pierces the substrate it is repairing, performing a modest violence upon what is to be mended, and reminding each of us of our sensitivity, vulnerability, and mortality.8

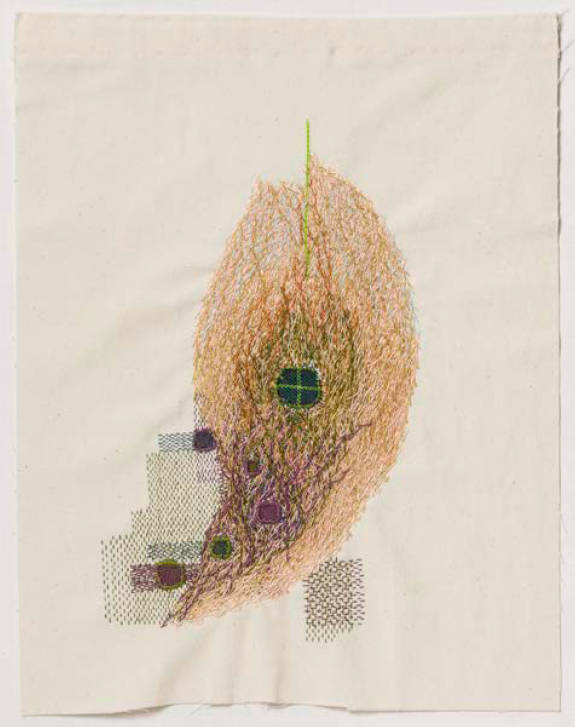

Mark Newport, Mend 4, 2016. Embroidery on muslin, 17 x 13 inches. Photograph by Tim Thayer. © Mark Newport, all rights reserved. Courtesy of the artist.

Rather than simply patch over the proper “wound,” Newport’s work lingers in the cut produced by the suture. It appreciates how complex the work of care is and it refuses to reduce care to a simple corollary of violence. In pieces such as Mend 4 (2016), Newport starts not with a hole in need of repair, but with a complex web of stitches that make it difficult to say what came first, then second. Rather than work to cover over a voided-out space, or to deny the presence of violence within human relations, the patch at center of the work catches us all in its crosshairs and produces what might best be described as a new, networked sense of relationality. Newport’s mending relieves masculinity of its wounded duty and dares us all to consider different, less clear-cut paths of relation and being.