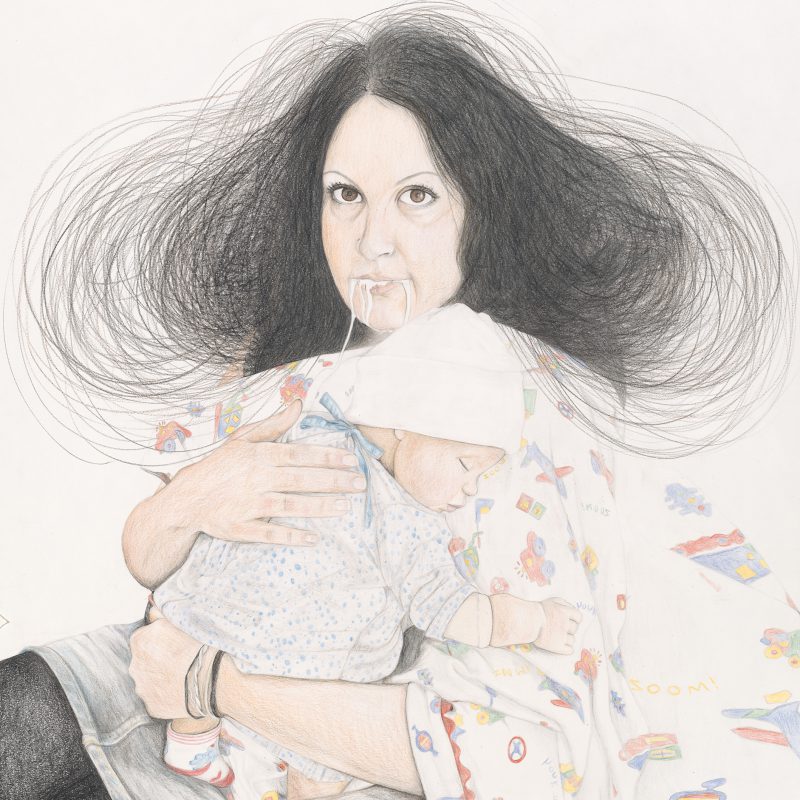

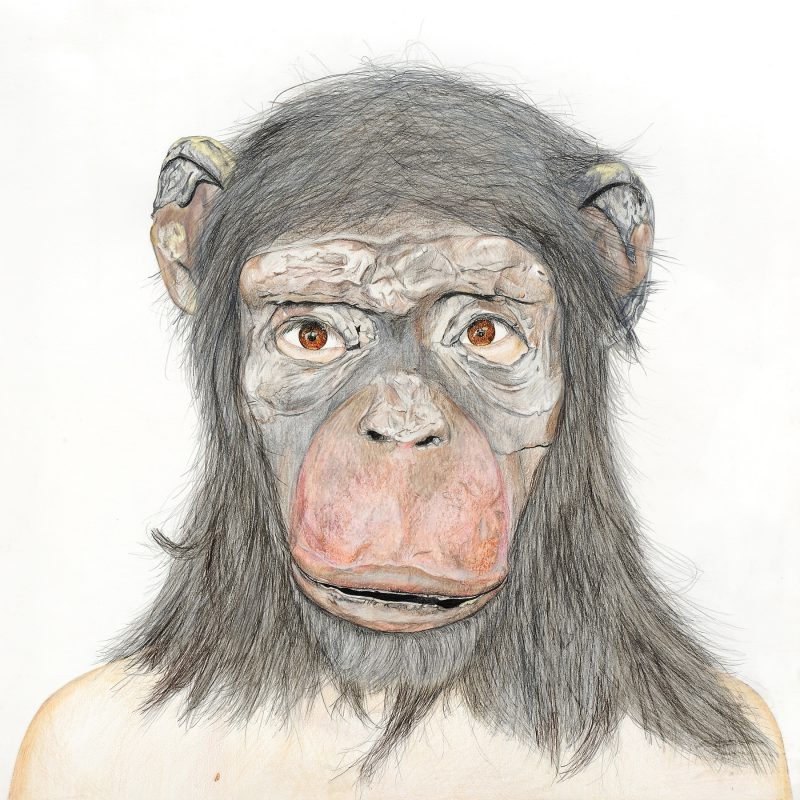

In this age of Internet searches, dystopic/utopic futurism, virtual communities, and technology’s promise of hope, artist Desirée Holman explores the unconscious underpinnings of our scattered, spilled, and discordant zeitgeist. Holman works across mediums—video, drawing, performance—integrating and conversing in an interdisciplinary mode of fantasy and performance. Her works underscore common anxieties about the unknown—what is beyond the empirical, visible world whether it be unarticulated social structures or a belief in aliens. Holman’s work reveals our desire for knowledge about that which is difficult to perceive, the possibly unknowable; concepts often addressed within fantasy, counterculture, technology, and relationships. She employs the edge of our known world to mine the depths of a sometimes mutual, sometimes exclusive quest for positive paradigms and pedagogy concerning the body, communication, and the sociology of inequality. Holman’s work points to the questions that catalyze different communities and forms of study whose inquiries often produce very different outcomes and perceptions of reality. By bringing together, sometimes synthesizing, sometimes contrasting these different modes of inquiry, Holman provides a prism through which one can investigate the commonality of the questions and their divergent answers. She also presents and creates alternative spaces within her work, which allow for empathic experiences and role-playing as another mode of investigation. In Holman’s work, fantasy itself—as an alternative, parallel space—is a medium through which she presents conflicting points of view, which address similar sets of questions. Her work Sophont (2013 –present) utilizes new age philosophy, psionics (telepathic theory), alien abduction stories, aura photography, and new technology to examine the history of the Sophont and its place within our contemporary imagination. Sophont, a term associated with science fiction defining a being with intelligence equal to or greater than humans, is typically visualized as the almond-eyed alien. The performance and video components of Sophont features an intergenerational cast of The Time Traveller, The Indigo Child, The Ecstatic Dancer, and The Guide. In Troglodyte (2005 – present), Holman employed ethnographic studies of chimpanzee behavior as a reflecting pool for human social structures. In this work, performers dressed in full body latex costumes and acted out different scenes that Holman directed and documented through video and other mediums. In Heterotopias (2011-present), performers created their own avatars, which Holman reified through costume and then presented in a three-channel video work. Reborn (2009-present) explored the wish of motherhood and its complex nexus of desire and attachments. Studying the Reborn Doll culture of women who create and nurture highly realistic dolls, Holman envisioned the performers as if the mother was attaching to the baby, running in opposition to various psychological theories, which suggests the baby seeks to attach to a consistent and stable caretaker. Reborn acknowledges a profound need for attachment, for caretaking and for physical location in an environment of changing bodies and psychologies. Drawings of women with fluid (breast milk?) leaking out of the mother’s mouths while their hair whisks up and around their heads like electricity seeking ground capture the tensions around emotional overflow, biologic thrusts, and the sitting, holding mother.

This interview is an excerpt from a three-hour conversation in Holman’s Oakland, California studio on November 15, 2016.

Desirée Holman, Outgrowth, 2009. Color Pencil on Paper, 16 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the Artist

Kate Haug: You refer to equality in your work. How do you see your work thinking about or posing questions about equality and groups?

Desiree Holman: Well, for each project there are different frameworks. In Troglodyte from 2005, that work was very much looking at a range of issues like the origin of animism, religion, that sort of thing. But, it also looks at reciprocal altruism and violence in mammalian groups. We’ve really projected our own lifestyle onto apes and also set to distance ourselves at the same time. And we share a lot of the same DNA, so it makes sense. Troglodyte looks to mammalian behavior to consider equality As another example, Reborn, vacillates between two places. One point underscores this kind of reverence of this ancient nurturance that’s involved in the maternal instinct and everything that’s incredible about that. The other side of the coin is a very intense violence or brutality. Kin selection means you would favor your own child at the expense of another life. And there’s a fierceness to that. I’m a mother and I feel that. I also feel suspect of that instinct, but there are moments where I feel this protective fierceness very deeply in my humanity. It makes the system work, but it has a dark side. So I think in some ways I’m looking at really really really deep-seated parts of humanity and how that relates to xenophobia, how that relates to racism, these things.

Because you were talking about these more biologically driven modes, and I see your work as very much located in the body—but also asking questions about the body. I’m going to skip to this other question. I feel reproduction and sex are being separated out at this point—you have all these women freezing their eggs, you have surrogates, the way we reproduce is radically changing. In the past, sex and reproduction have given us timelines for lives. As women we experience all these different hormonal cycles, from puberty to menopause, through childbirth and pregnancy, our whole lives in some ways can be attached to our biological beings.

I noticed in the Sophont image that you work with, it’s a genderless creature. It has no genitals and that signals this future where sex and reproduction are separated completely from one another. The Troglodyte figures are more sexed. They have breasts, they have hair. Could you talk a little bit about reproduction and sexuality? Where you think it’s headed? Any thoughts about it?

Desirée Holman, Sophont, 2015. Three-Channel Audio/Video Installation, total video run time: 12 min. Music by Angel Deradoorian. Courtesy of the Artist and Aspect/Ratio

It’s hard for me to speculate on what’s going to happen. There are certainly fantasies that I’m invested in and like to engage with. Of course, we know generally that first-time mothers’ age is changing radically around the world. Birth rates are changing. Gay marriages, and adoption within gay marriages is becoming more acceptable. And obviously, that’s not universal, and there’s lots of major setbacks, and that feels threatened right now for a lot of people for good reason. The trajectory of the gray alien in the popular imagination has been a figure that went from being very fair skinned and pale in the ‘50s with blue eyes and looking like a human being to something that was gray skinned in the ‘60s when we have the Civil Rights Movement going strong. There are all these reports and drawings and artifacts of alien encounters. I don’t care whether they are true or not; I’m just interested in the symbol of the ET. So there’s this history of imagining this symbol moving away from any kind of sexual dimorphism to something that is even beyond androgyny. With this symbol you see a huge brain develop over time, which I tend to interpret as this moving beyond the triune brain. This building beyond the reptilian, the mammalian, the neocortex, and moving on. And you see all kinds of ethnic features fading away, becoming vestigial. I think it’s a problematic fantasy, and it also makes a lot of sense because we’re embroiled in so many problems, not only around sex and reproduction but around ethnicity and the nation state. I think that this particular symbol resonates for us because it’s something that seems to have transcended these kind of earthly biological problems.

Right. The body is this petty inconvenience for our truer nature or something along those lines. You employ figures and forms like the chimpanzee, the Sophont, the Indigo Child, which circle our present day incarnation of homosapien. You create this Darwinian solar system around us 21st-century humans. You also title a piece Atavism, which is a word I learned thanks to you. It is a biological term for an evolutionary throwback. Do you think our current form, our 21st-century bodies are more temporary than we typically like to believe? Do you believe we’re in an evolutionary moment?

Yeah, I do, but I think if you accept Darwinism you always have to believe we’re in an evolutionary moment. I guess I’d just say, “Why would we be the apex?” We can’t be. We’re so flawed. I don’t know why an evolution would stop. Actually I do: natural disaster, disease. But in the relative good-standing that we’re in now… if we are to accept Darwin’s theories, which—who knows somebody could come along tomorrow that totally blows the cover off that. But right now, I’m believing in Darwinism. And yes, I think we’re still moving. Trump’s election is a horrible blow to that trajectory in my opinion, but I suppose that’s me putting a moralistic framework on what I think is a forward movement.

Do you think that the networked self is part of the evolutionary pathway or framework?

I think it could be. Yeah. I like that idea. And I’ll just say I like a whole lot of ideas. And I don’t feel a responsibility to make sure they work out cleanly or reject one idea at the expense of another, because who knows? Maybe it’s all true or none of it’s true. I love the idea that we’re all a computer simulation. That’s really intriguing, and maybe it’s accurate.

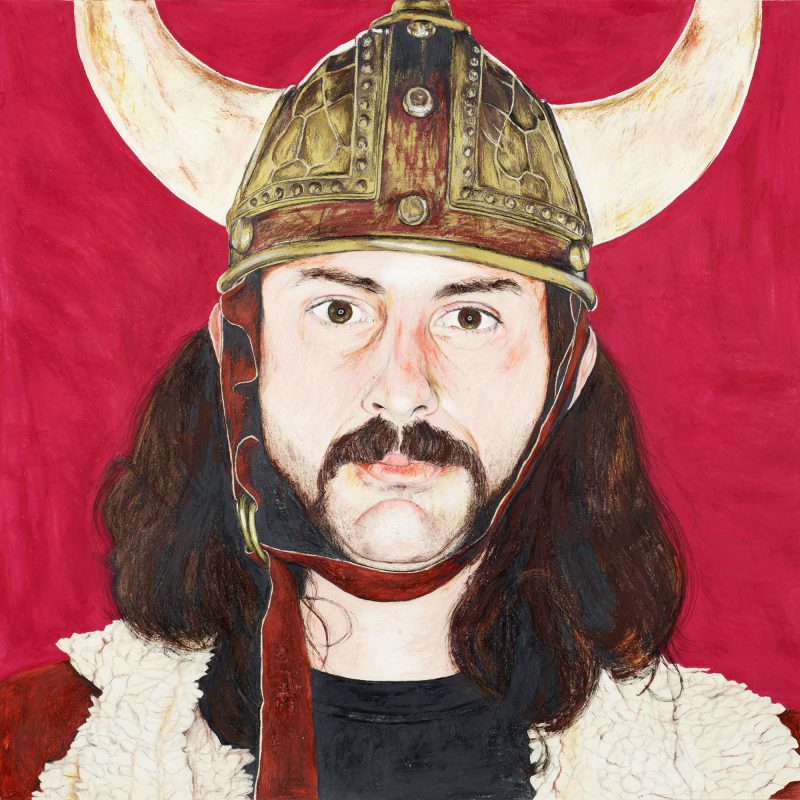

Desiree Holman, Indigo Child, 2015. Pencil, watercolor, acrylic on paper, 16 × 16 inch. Courtesy of the Artist and Aspect/Ratio

In her Troglodyte essay on your site, Dr. Lera Boroditsky writes, “Passing on ideas can work much faster than passing on genes. Though being a recent evolutionary development, it is more error-prone than passing on genes and certainly not as enjoyable,” smartly acknowledging this new world of information technology, possibly underscoring the separation of sex and reproduction. In the same essay, she also mentions pheromones, which I really appreciated. I’m personally very interested in different forms of knowledge production and pheromones fit into that. It’s knowledge produced by our bodies, which also heavily influence our reproductive choices. I often wonder if screen culture is limiting our knowledge production and our perceptions of the world because it’s so focused on the eyes and vision. Vision dominates over smell, touch, taste—all the other ways that we imbibe our lived world. If you imagine someone with their screen, alone in the room, they’re in their own smell environment, so it is a very narcissistic, masturbatory smell environment.

I was wondering if that related, in a sense, to why you employed dancers and performers. When you ask people to come into a performance, you’re giving the whole breadth of experience–all the smells from the dancers, their pheromones, the rustle of their clothing, all the subtle sounds. There’s that nuance of a lived experience, which is much different than a screen experience.

To cycle back around to this idea of body knowledge versus brain knowledge, I really truly believe that I’m thinking with my hands. I’m thinking through the ideas with my hands and I’m actually actively de-coupling from words sometimes. I do a lot of reading and then I almost seek to forget it. And let the ideas filter down through my body and out through the things that I make. There’s that happening and that relates to this sense of wanting to remove the lens sometimes and bring the performers close to the audience. There’s this little bit of a selfishness that I also want to be able to touch the performers. I never thought of it, but I’m sure it’s quite right to be able to smell them and see the textures of their hair and their skin and their clothing up close. And to explore the movement vocabulary with them that’s in the videos.

The amazing part of working that way is it is physical and it does capture these very basic things that are part of our architecture, they’re so pleasing. You’re hungry, are you going to eat a plate of lasagna or stare at a picture of lasagna on a screen? Unlike the video, the dilemma is that it’s very difficult to control the pace and framing of live performance. You don’t necessarily have the tools to create these abstract spaces that exist in my videos. I’m really excited to work in VR for that reason—to work both with the physical but also created, time-based content. To be able to place a viewer’s body inside an abstract space that also has a kind of feeling, touching component.

Desirée Holman, Dancers Dancing in Their Own Digital Ectoplasmic Cocoons 1, 2010. Color Pencil Mixed Media on Paper, 24 x 36 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions

I love it in one your artist’s talks, when you talk about Sophont, you say that you read both Internet conspiracy theory and original scholarly work. I think the role of the artist is to do exactly that. You employ academic ideas and also so called fantasy ideas–those of science fiction and marginal communities. In a way, all these forms express similar human desires, which I think in your work are to change the body, to have an utopic outcome and not to be bound by the traditional mores of the human body.

At this moment, I think the arts and humanities play much more important role than ever, because our problems are not technological, they are political and social, bound together by unconscious fantasy and disparate lived experience. How do you see the role of fantasy providing a space or a bridge?

Fiction is a safe place to explore really uncomfortable topics because it’s not real. And so it can bear a strong resemblance to reality. It’s like comedy in that way. You can tackle things head on, without tackling them head on. I use the word fantasy, but you could easily use the word fiction. Furthermore, I think role-play is important in terms of engendering empathy and taking on an alternate point of view, which is critical to solving our problems now.

I like that, fiction. I think fantasy locates more desire. We associate our desires with our fantasies.

Definitely. It’s a Freudian term. And there are a lot of dragons there.

How did you become interested in using dance as part of your practice? You typically don’t seem to employ spoken language in your video pieces. Instead, you use music, chant, dance, action, costume.

Such a natural progression that it is almost hard to parse out how that happened. I think there’s something in the improvisation, where the dance comes in or thinking about unity. I’m going to go back to the Troglodyte example. I was working with it before then. But, I started working with choreographed group dancing in Troglodyte in 2005. It came out of reading these ethnographies of animals in their natural habitat. Of apes, in particular, and how the apes would do these dance-like displays—which seemed to have nothing to do with gaining status in the group—when they would see a waterfall or when it would rain a little bit. Usually, the displays that have been recorded were to gain status or when something happened in the group. It all had to do with social hierarchy. The apes had been observed so many times, in these particular circumstances, coming upon a waterfall and bursting into dance together. It wasn’t exactly synchronized dance but that’s where I took it, “Let’s do this, let’s do it together.”

Basically, they’re stoked because they found a waterfall.

Well, that’s the theory. That’s what it seems to be, but who knows. But I’m taking that one. That it’s just overwhelming and awesome and they’re moved to this expression. Also maybe that’s the seed of animism. Maybe those are the seeds of religion, right there. That relationship, in this case a relationship to the natural world. It’s something that came out of the history of looking at the body, and grouping, and behavior. And I’m really skeptical. I’m not great with language. I think, as an artist, it is the place that I struggle the most. So, I don’t tend to want to work there. I don’t tend to really want to write about my work, but I do, because it’s important. Funny enough, the project I’m working on now is all about language.

Desirée Holman, Atavism, 2012. Color Pencil on Paper, 16 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions.

What made you move toward language?

I started studying Chinese, Mandarin, casually. And I realized it was not something I could not do casually and really move forward in a significant way. But I also just started to see things anew. The biggest turning point was having a moment where I had to say something to someone else about “I’m gonna come next week,” or something like that. And it needed to be in Chinese. It was the first time I was left with no one to help me. I couldn’t pull out my phone dictionary. I couldn’t write it down. I had to say it. And I realized that in order for me to construct this sentence, spatially, I had to conceptualize time, the forward movement of time, as pointing downwards. I’ve always conceptualized time through the English language, as being horizontal, that the future is to the right, like a timeline. That was just the first kind of moment. Shifts in thinking. Not only spatially, but in other ways. So I’m doing a project that has to do with a group of learners who were at a community-based center that mostly serves immigrants and people who are trying to get their GED. It’s this super diverse group of people that meet weekly for years and are learning Mandarin. Some of them are heritage learners. I have gotten really interested in this group, because it’s like a temporary new society that’s created. A lot of the external markers are plateaued in there. I got interested in this concept called ‘the third place.’ And it describes this abstract place where an intermediate learner has to decenter from their own point of view in order to step into a new point of view to keep progressing with the language.

That’s amazing.

Oh! Thank you. I’m really excited about it.

Let’s talk about Reborn for a little bit. When watching the video sections of the work, I was curious about head-scarves and face veils. What was your intention of using those within that context?

It didn’t start out with that intention. I was working with somebody in the studio and we were trying to find a way to mask the women to help them feel less inhibited since they were going to be dancing in their undergarments on camera. So we had actually looked at niqabs, ninja masks, and super hero capes and so we were like, “Okay we can do something that is a hybrid of these three.” And it ended up reading more like a niqab. If you deconstruct it a little bit more you can actually see some of the elements of the other things but I definitely feel like, in the end, it reads as a niqab more than I had intended. I feel critical of the type of feminism that would purport to make a prescription for Muslim women or to talk about their “oppression.” That’s not the point of view that I’m coming from, and at that time there was so much in the news about Muslim identity so the niqab was fresh in my mind. There are images in the video that end up kind of pushing back against a very straightforward read of these women in these face veils that I think seeks to unravel any single interpretation. But ultimately the project is rife with mis-readings and it’s something I’ve come to embrace about the project and feel is one of its strengths.

Desirée Holman, Reborn, 2009. Three Channel Video, total video run time: 10 min. Music by MEN and T.I.T.S. Courtesy of the Artist and Aspect/Ratio https://vimeo.com/58137305

My next question is about Bucolic Life (2003). You must have made that before Reborn.

Way before. That’s a really old project.

I stumbled upon it and I really liked it. You’re posing yourself with these mannequins in these quasi, stereotypical family snapshots. So I thought they really channeled these commodified expectations around motherhood or domestic moments. What inspired you to make those at that moment?

I think my desire to try on that role. That’s really old work for me, and I don’t tend to include it now or present it that often for a lot of reasons. One is that I’m playing an active role. I realized that I’m much more interested in being a director and have other people do the role-playing. Also, I grew up in a very atypical family structure, which included living in foster care and being adopted. It wasn’t horrible all the time, but there were many situations that were not desirable. And so I was often looking outwards for role modeling. It could be catalogs. I was really invested as a child in the Sears catalog and that presentation of domesticity. And I think that particular project called Bucolic Life from My Unreal Existence is a continuation of a practice I had in childhood that was playing and imagining myself in these family scenarios as a way to get closer to it or understand it. It’s coming from a distance because it didn’t have… At that point, I had never played any of those roles as the child or the mother in a scenario like that. It also has some criticality to it. It’s both critical and desirous of that situation.

For some reason, I really related to those pieces and felt there was a sincerity to them. The images were an emotional investigation of both desire and commodification. Desire—you’re the protagonist, you’re desiring. Simultaneously there is this awareness of the commodification of what you desire. You show what it’s like to be caught in between those two things—to desire and to also be critical of what you desire. It’s one foot on both sides, which is an interesting and productive place to be but also can be a really hard place to hold for yourself.

Somehow, I’m fairly adept at that. Being in that place. It continues to be not that exact narrative because my work hasn’t continued to explore those themes, particularly in the first person. But it still holds a lot of contradictions and by and large, really comes from a place of sincerity. Which I find doesn’t always translate, which is okay. I don’t intend to control reads of the work. A lot of people do read a tongue-in-cheek humor into the work.

That’s interesting.

You don’t?

No. The work has an emotional sensitivity to it. I think you’re honestly interested in these different spaces. You have empathy. You have empathy for the academic, you have empathy for the people who have UFO experiences. You’re really seeing this as our human collective, human condition. If you have empathy for yourself, you have empathy for these other people, too, because we’re all struggling with these same sets of questions in some ways. The struggle might manifest differently for different groups but it serves as an underpinning. That’s why you’re saying these different groups all seem to have this idea for a utopic outcome or they all want to change their bodies. I think those are very, at least for western culture, very universal underlying questions. You know when work is snarky or flippant. You can feel that. People do that for different reasons, there different kinds of aesthetic and ideological battles that can expanded though flippancy and snark. It’s a tool, but I don’t think it’s your tool.

I had this question about the video for Heterotopias, which possibly relates to what we’re talking about, which is the costumes that you employ. The costumes seem to have a homemade or store-bought quality as if it’s the wearers’ fantasy that is being presented rather than the viewers’ fantasy. It’s not so much that the viewer is transported into another world but the wearer transports themselves into another world and the viewer witnesses a fantasy of self. There is a certain campy quality that I find in that, which I relate to drag, where the fantasy is really embodied by the wearer and there is a transformation. Can we talk about that sense of camp, which I think is different than a tongue-in-cheek, wink, wink strategy?

Desirée Holman, Fantasy Character Framework (a hypothetical primary framework), 2010. Color Pencil Mixed Media on Paper, 16 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and CULT Aimee Friberg Exhibitions

Well, you’re right. The characters were driven by the performers, not by me. So they are their version of themselves that I was just able to, with their input, articulate. So most of the costumes are handmade—not every element—but some down to the shoes are handmade by me. I don’t think of it as camp, although I don’t contest that categorization. I think it grows out of all the years I spent as a child’s entertainer doing so many different characters.

What do you mean a child’s entertainer?

A children’s entertainer. In commercials. I did entertainment at birthday parties, I did…

In costume?

Yeah. I preformed in both public and private spaces in character. And I think that that sensibility informs my work way more than I even realized until maybe about five years ago. I have this one incredible story that I want to share that I think for me tells a lot about why I work the way that I do, and with the aesthetic that I work with. So this is in Richmond, Virginia, probably like 1996. I was hired to be an entertainer at a kid’s birthday party, a little boy. I think he was five and he lived in a project. I went to the party, and I was dressed as Barney the purple dinosaur. I rolled up to the party, and I see the kids before they see me, or Barney… See Barney, and see all these kids, especially this one kid. He is screaming, fighting, and super violent. I mean really shocking, really, really, really violent. It turns out, it is the birthday kid. And I walk up and am trying to find an adult and there’s no one around. And then the birthday boy sees Barney and runs up to Barney and his character completely changes.

He’s now super soft. He just asked Barney to hold him, and I could not believe it. I sat there and basically held this child and used my Barney voice. I didn’t do the things that I was planning to do. I just held him and I said, “I love you,” …Saying the things that he wanted to hear from the television. It was so powerful to me to see this child change on a dime, that I was able to facilitate something for him in this very temporary space. And I think he led me around, he wanted to show me some things too. But I spent that whole time really with him, holding his hand, or holding him. And he just wanted to role play those things, and it was like, it seemed to me that it was amazing to have… Like there’s reciprocity on the television show but it’s static you can’t… You have a call and response but it has to be timed perfectly on behalf of the viewer. But this time I could respond in real time as Barney.

I think in a very different way, I’m trying to do the same thing with the performers I work with that I’m trying to create this space. So, maybe in some sense that childlike aesthetic has locked in, this particular history that I have, this kind of playfulness, this potential that’s so ripe at that age for fantasy is something that’s just been really close for me. If I have that deathbed moment, and there’s the life Rolodex flashing by, that memory with the child’s birthday is so potent, so powerful even in all the other beautiful memories that I have and treasure, this one I feel surely will come up for me.

It’s an extremely beautiful exchange. A beautiful example of how real need can be met in fantasy.

Yeah, it was incredible, and I think that I have continued to seek out these temporary exchanges that have the potential to be transformative in a positive direction.

Going back to the mother/child relationship, we do have this sense of permanence with our mother, which I don’t want to assume too much about your life or experience, but maybe you may or may not have had. But I think our sense of time is different when we’re children. And so your time with your mother feels permanent, but then the rest of your time and your adulthood seems temporary. It’s this different sense of time and space, and so that moment you had with the child was I feel somewhere in between temporary and permanent maybe for him. Just because of his long stemming history with Barney, the TV character. It’s so moving.

It’s really moving. Yeah. I’m really thankful that I got to experience that. I mean anytime we witness some desperate deep pain (which I feel our country is dealing with right now) and get to look at it from either a cultural or personal perspective and experience positive movement through that, even if it’s just inches or steps forward or back, it’s incredibly powerful to witness.

It’s just for the moment. It’s going against the mainstream culture in some way to say, “No, these openings are valuable even if they’re three seconds long.” In Sophont there is a mix of science fiction and technology, both old and new, which all hint at some sort of spiritualism in utopianism. Do you find in all of these different narratives a search for spirituality? Where is the spirit—in the machines, the body, the cloud?

That’s like one of the biggest mysteries for me in terms of what I’m doing. I don’t know how to place spirituality. I know that it’s there, that it’s in the work. I’m really struggling to talk about it. I hope that I can get there sooner than later, but however long it takes is how long it’s going to take. I really see in Sophont those different character types—The Time Traveler, The Ecstatic Dancer, and The Indigo Child—as going through these trans-generational transfers of information and values. They’re all, in some ways, representing different parts of what has been a counter-cultural perspective and are coming more to the mainstream in that intergenerational transfer.

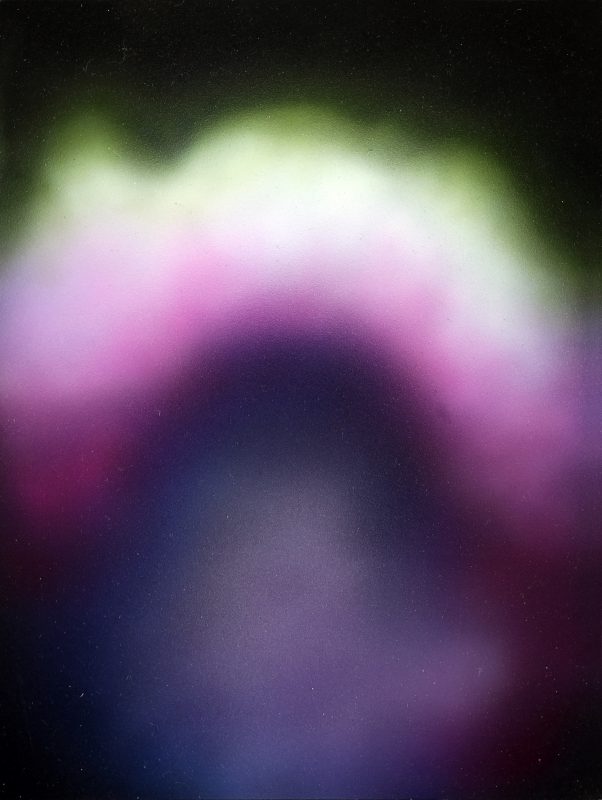

Right before you arrived I was going back and reading Benjamin’s “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” because I’ve been thinking about these auras that I’ve been creating through very specific and rigorous, albeit outdated, technology. A huge part of my budget has to go to shooting on an infinity cyclorama stage, which has the concave curved wall and floors in order to achieve the color contour around the performer that you see in the videos. I think of those color outlines as auras. This process and aesthetic was originally inspired by occult photography and ectoplasm. So I think of these color halos or auras as being a kind of digital ectoplasm.

What’s ectoplasm?

Ectoplasm is seen in occult photography and is a byproduct of working with a psychic in some kind of spiritualistic trance in which ectoplasm emits from the psychic. It is a semi-transparent (sometimes physical, sometimes only visible in the photo) byproduct of a ghost or a spirit that would manifest though the psychic. But it was probably trick photography. I mean at the time it was really meant to serve as a testament to how real these things were. In retrospect it looks pretty clear there were double exposures or that was just cheesecloth coming out of their mouth. And I think the same with the work that I do it’s very clearly transparent and it’s very clearly a dated technology. But I am still very attached to the aura having meaning and an aura having an emotional resonance.

To wrap back around to the Benjamin essay, I’m still not really sure how to locate my work in that essay and I think his idea of the aura doesn’t have anything to do with aura photography certainly. But it’s another thread that I think is relevant that I’m trying to tease out. He has talked about moving away from the ritualistic in contemporary art. For me, when I’m working with these performers in that space, I actually do think there is some relationship to ritual. Yet, these auras have a complicated meaning. I’m saying that, simultaneously, I realize that they’re transparent and artificial, but I also see them as pointing to a metaphor and maybe even moving beyond a line of metaphor. But anyways at the very least something that has heavy emotional resonance.

Desirée Holman, Aura, Buckminster Fuller, 2014. Acrylic on Panel, 12 × 9 inches. Courtesy of the Artist and Aspect/Ratio

In Sophont, you have these different characters—The Guides, The Indigo children, The Time Travelers, and The Ecstatic Dancers. How do you see them relating to one another? You already said it’s an intergenerational transfer of information, but I was wondering if you wanted to elaborate?

I think in some ways they’re all embodying some kind of pushback against capitalism. That’s the common thread between these groups. So the elders, The Time Travelers, they are really an amalgamation of a bunch of different ideas, but spanning from back-to-the-landers in the ‘60s, folks in that time frame who maybe have totally changed their ideologies now, but at one point were Buddhist and anti-capitalist. It’s also inspired by the Singularity or the radical fairies of the ‘70s; they are all long haired, they can be androgynous. If I could cast exactly as I want, they would all be like men/women Gandalfs. I mean, potentially different ethnicities, but some kind of version of that.

The Time Travelers are all wearing these psionic helmets that are kind of tin foil hats. The Ecstatic Dancers are inspired by a contemporary practice that’s pretty alive in the Bay Area. I was inspired by a particular form of ecstatic dance that uses a really spiritualized rhetoric in their dance. Their dance floor is a sacred space and they dance with a very directed intentionality. I would call them new-agers, although they may not use that moniker to describe themselves. I place that in counter-culture, although a lot of that is pretty mainstream here and in different places.

The Indigo Child. The Indigo Child I created is like a mash-up of different things, including the straightforward Indigo Child, which is a self-proclaimed identity that can go as far as believing your DNA is altered by extraterrestrials. The kids, born after the Harmonic Convergence, are supposed to usher in a new phase of humanity and bring about world peace. Their auras purportedly glow Indigo. That’s one way that you can tell someone’s an Indigo Child. There are other ideas informing my version of The Indigo Child, including Count Richard Nikolaus von Coudenhove-Kalergi’s Race of the Future combined with androgyny. These character types all embody counter-cultural ideas that I think—in some ways, if you distill them enough—are pushing back at capitalism.

Or pushing forward to someplace.

Yeah, socially. It’s definitely an imagination for the future.