Rudolf Frieling, Curator of Media Arts at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, developed an interest in Bruce Conner’s work soon after relocating to the Bay Area and has subsequently acquired several of the artist’s films for the museum’s collection. Frieling’s conviction that Conner was not only one of the twentieth century’s most important experimental filmmakers, but also one of its more significant artists, led him to suggest initiating the retrospective Bruce Conner: It’s All True, which was co-organized with New York’s MoMA. I spoke to Rudolf via telephone in order to find out more about Conner’s films and filmic innovations, and to ask what in particular distinguishes the artist’s approach as contemporary.

Gary mentioned that the seeds for Bruce Conner: It’s All True were sown when you acquired Conner’s THREE SCREEN RAY (1961/2006) for SFMOMA. What year was that, and what about that moment in particular prompted you to consider organizing this retrospective?

It actually goes back all the way to when I joined the museum in 2006. After a short while I realized—as I was assessing the status of the collection—that we did not have a single time-based work by Bruce Conner and I thought, well, we’ll have to change that at some point. I was subconsciously, I guess, waiting for the right moment to meet Bruce and start a conversation, but before I could actually even think about that properly, he died. That was in 2008. I didn’t quite know how to respond to that, so I waited a while. Then, a year later, in the summer of 2009, I approached his estate and said I would really love to meet and just discuss what might be possible. We met and Michelle Silva, his editor, showed me THREE SCREEN RAY, which I hadn’t seen, obviously, because it hadn’t been released. It had only been shown once or twice as a single-channel composite projection in screenings, but it had never been installed. It hit me at that moment that this piece would be a fantastic contribution to the museum’s 75th anniversary show in 2010, despite the difficulties that Bruce had with almost every institution, and certainly including SFMOMA. We also had a long history with him, and there were more than 20 works in the collection—assemblages and works on paper, an ANGEL, and so on—but as I said, no film work. He’s one of the most important Bay Area artists, so it made sense to include that work in the exhibition as a sort of homage. It was fitting for a number of reasons. Have you actually seen it?

Just snippets.

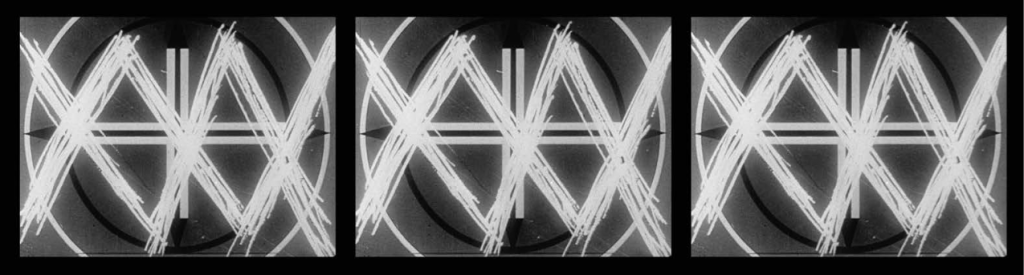

THREE SCREEN RAY, 2006. Three-channel video projection, black and white, sound, 5:14 min. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

So if you remember, it is not only a sort of digital remix of his 1961 film COSMIC RAY, but it actually goes beyond that, and includes other images as well, and other image sources. It seemed to me almost like the sum of his filmic work with found footage. That’s one aspect. The second aspect was that it was a review of not only past works and past footage, but also technically of what he had considered essential up to that point and it really achieved the shift from film to digital. So while until the early 2000s Bruce’s mantra had been that “film is film; it needs to be celluloid,” all of a sudden he understood that he could rework his own work digitally with the same artistic integrity.

Interesting. This notion of reworking or repetition was going to be a later question for you.

Okay, let’s go back to that later, I’ll just finish this one thought. So there was a frantic and very urgent push to bring this one work into the collection, and then we presented it with two of his other film works from around the same time, BREAKAWAY (1966) and MEA CULPA (1981), and added more recent contemporary works that were all centered around music and appropriation, found footage. We had this idea from the very beginning that we could explore how Conner relates to contemporary artists, and at the end of that presentation in 2010, which met with such a phenomenal success with the critics, but also with the public, it occurred to me that we might have a really, really important job to do if we did a full retrospective, considering that his last so-called non-retrospective organized by the Walker Art Center had happened 10 years before in 2000, and obviously did not include the last nine years of his work. And, given our renewed and emphasized commitment to California and our specific context here, that was the first time ever I got an immediate yes from our director for an exhibition proposal.

Good! You said you came here and when you looked at the collection you noticed a lack of Conner’s time-based works, but had you been thinking about him in Europe? Was he someone on your radar?

No, but in my previous job at ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe I didn’t have the same responsibilities, so there was no need really to think about acquisitions. It was also a very different context. As the media curator at SFMOMA, I’m really confronted with a specific expectation, which is very often centered around the notion of working with or acquiring new media, and I wanted to make a case for a much larger understanding of time-based performative works. So film would necessarily, obviously, be part of that, although I didn’t want to start a film department or a film collection of sorts, but rather to respect whatever medium artists were working in, and that obviously includes Tacita Dean, and others, who really insist on using film as film.

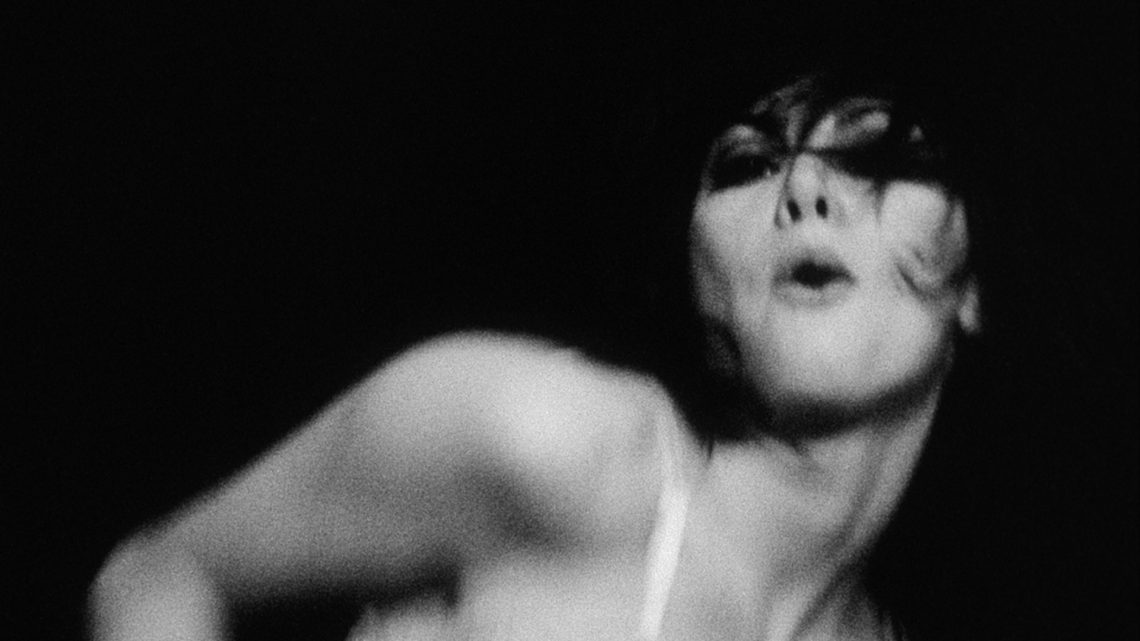

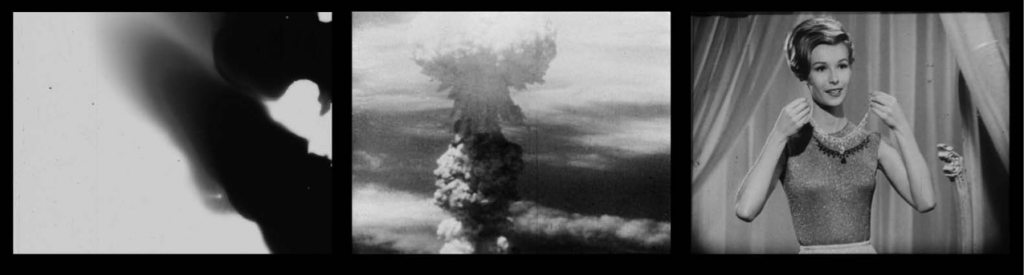

MEA CULPA, 1981. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 5 min. Courtesy Conner Family Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Well, he’s an unusual artist, Bruce Conner, in that he can excite a number of curators at one time across departments. So apart from you, Gary and the photography department are also invested in his work. He’s a bit of a gift in a way to a museum. Can you talk about what you see as his importance specifically to experimental film making or media based art, whether it’s the kind of technical innovations he made, or just more generally?

Well, it’s a complex question.

Yeah, it’s a big one.

I’m not sure I can answer it so quickly, but let’s say there are two different ways of looking at media art histories. One is that you consider innovation and technology, and I would argue that he was not in the business of addressing innovation and technology per se. The other is about a very specific time-based performative experience, and developing a language and a concept, and I think that’s where he’s really, really strong, and arguably one of the first artists to address that in such scope. I think that’s why he became so successful early on, after he made A MOVIE. His career mirrors the histories of a lot of artists within the context of media art, in that they really, really struggled to find a place in the visual arts, although that was where they were aiming to be. Conner started as a painter and a sculptor, and an assemblage artist, and he tried to integrate his interest in film into his gallery presentations, but that didn’t work at the time, understandably. It was just stretching the boundaries of what one could envision as art or institutionally collectible. And so, although it wasn’t necessarily by choice initially, he then embraced the idea that the place for these films would be the cinema and the theatrical screening, and then, of course, it became a sort of experimental or underground niche for that kind of work. And so there are a lot of people who know him as either the assemblage artist and painter, or the film artist and experimental filmmaker.

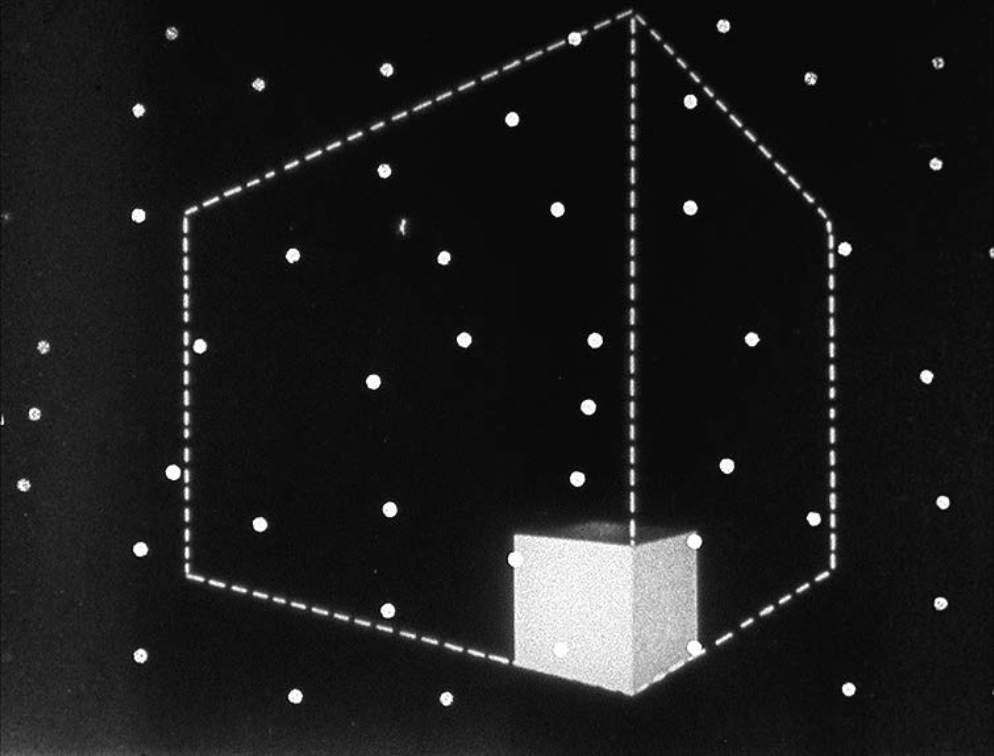

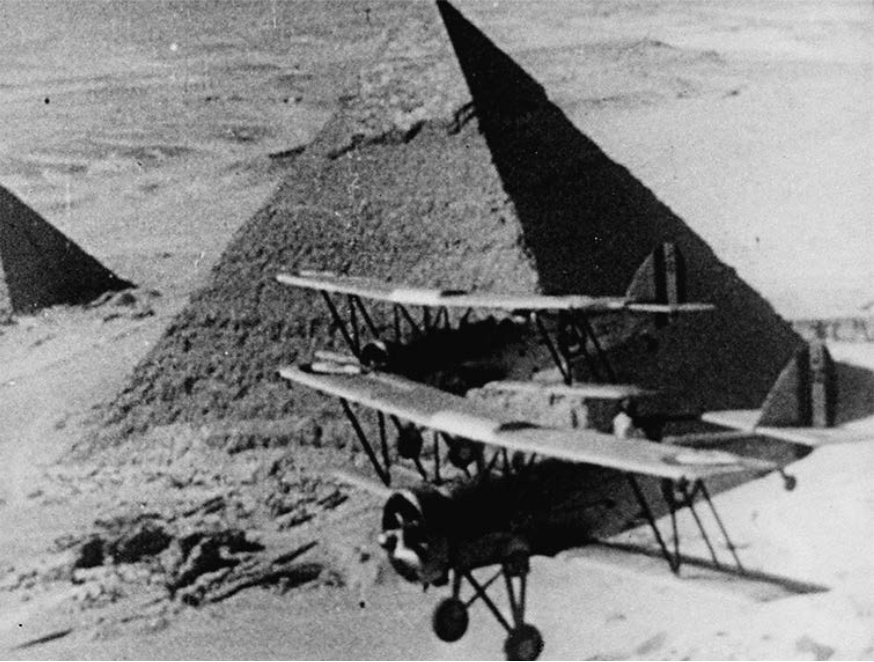

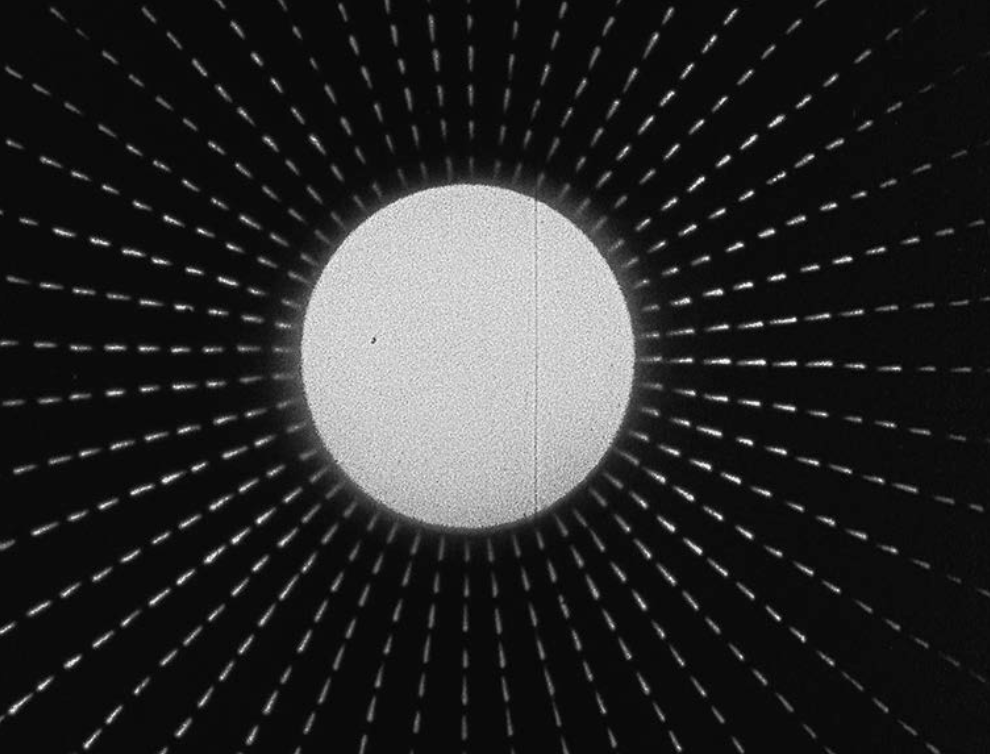

A MOVIE, 1958. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 12 min. Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Accessions Committee Fund purchase) and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, with the generous support of the New Art Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A MOVIE, 1958. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 12 min. Collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (Accessions Committee Fund purchase) and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, with the generous support of the New Art Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

That makes sense because it seems that the way that his practice has been positioned in this exhibition is that everything cross-pollinated everything, so that he imported techniques from film into assemblage and vice versa. The distinction—was he a filmmaker or was he an artist making film—could almost be seen as semantics. I can’t remember where I read, it might even have been in your essay, but he was quoted as having said that he was a “factory working on his total environment,” well before Warhol.

Yes.

Was it something he said later in life, with hindsight, or do you think he was always aware of working across many different media?

Absolutely. I would say whatever he did in film was really time consuming and I think he just psychologically, but also physically, needed to do something else, parallel. So I think one can argue that he’s always made drawings, almost throughout his career, maybe not at the very beginning, parallel to whatever else was going on. The response to A MOVIE, and specifically to COSMIC RAY, the success of those films, forced him to review what he had accomplished in terms of always trying to skew the categorization of, “here is the appropriation filmmaker,” or “here’s the found-footage artist,” or “here’s the assemblage artist.” He made all these twists and turns and U-turns often, and very consciously, but not necessarily to his benefit. Certainly not to the benefit of his market; his galleries were constantly frustrated by this strategy and his cunning in undermining commercial success.

I respect that and I really get it, because it must have been so frustrating for him to be pigeonholed, or categorized by his output rather than by his inquiry. To me his work seems very existential, it’s really related to identity, to the twentieth century, to change, so for people to say things like, “oh, he was the father of music video” is too unnuanced.

Yes, yes, exactly.

You were talking about THREE SCREEN RAY as being, in some way, a summation of what he made previously. Is there a noticeable arc in the trajectory of Conner’s films? Do they progress and develop? Do the later films differ significantly from the earlier ones or are they really the same thing?

No, I think it’s probably fair to say that he spent his last nine years reviewing what he had done earlier. This notion of remixing found footage was key to almost all of his films, although he did also insert his own footage, here and there. BREAKAWAY is the big exception as it’s completely his footage, but its a driven, frantic, complex montage and its aesthetics show he’s continuing his exploration of the representation of the female body. I would say the beauty of a later film like THREE SCREEN RAY, is that it manages to function on the level of a fantastic response or resonance to the song “What I’d Say” by Ray Charles, but at the same time it explodes it and becomes super complex. I think that quality of Conner’s, that you never get to the bottom of his work, is something that I most appreciate after working for years now on this retrospective with my colleagues. The more you look, the deeper and more complex things become, and that applies to his films, to the assemblages, to the drawings, to almost everything he did.

Depth is one of the signifiers of a really great artistic practice, or not? And one of the reasons why you could position him as major, I guess.

You made me think about something just now that I can’t get my head around—when he remakes his films, what is left of the earlier versions? You mentioned in your essay that REPORT (1963 – 1967) was refashioned eight times, same amount of frames, same footage, but reedited: Is there—and this is just my technical ignorance—is there a print left of the preceding seven versions by the time you get to version number eight, or does each one have to be destroyed to create the next one?

Think of it like writing a book with a typewriter and submitting your first draft to an editorial process and then rewriting or adding or subtracting, etc. In some ways that was his constant process and it sometimes became public. He would show what he thought was the film, without knowing that this would only be a first version, and then possibly because some time had passed, or possibly because of reactions, whatever the reasons might be, he went back to it. REPORT is significant because he was so psychologically entangled with the fate of John F. Kennedy and the significance of his murder for American society, as well as the fact that at the time he was living close to his birthplace. There were a number of reasons that made it very, very difficult for him to find a final form for that film, although he probably felt that each version that he publicly showed was the work. THREE SCREEN RAY has a much more complex history because it actually returns to a number of different versions that he made in the ’60s. First he made COSMIC RAY as a single projection film, but then he made a silent version, a three-channel 8mm projection, I believe, for the Rose Museum in 1965. He clearly, very early on, had this idea of an expanded cinema in mind, but then obviously met technical challenges, and it wasn’t until around 40 years later that he felt there was an opportunity to review what he had done, digitally. So he produced a silent, unsynchronized version in 2006 called EVE-RAY-FOREVER, and then THREE SCREEN RAY, which is a synchronized musical version where COSMIC RAY is actually the center of the triptych.

THREE SCREEN RAY, 2006. Three-channel video projection, black and white, sound, 5:14 min. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Just even hearing you recount this history is complicated. How are the various stages in the film’s life tracked? Was he a meticulous chronicler of everything that he did?

Well, I can’t give you an answer for all the films, but there are records. There’s a film that we’re not showing in the retrospective called MARILYN TIMES FIVE, and it started off as MARILYN TIMES THREE. That exists, I believe, in Chicago. It may be in the collection of the Art Institute. In any case, there is a print that is in Chicago and there are a number of different prints in different archives. BREAKAWAY, for example, was followed by a somewhat similar, but also somewhat different, edit called ANTONIA CHRISTINA BASILOTTA, which is Toni Basil’s real name, and that’s in the collection of MoMA.

So he wasn’t one of those artists who kept detailed records or archives? A lot of this cataloging has had to be done retrospectively, then?

I think he was very meticulous, and he was very much aware of what exactly he had done before. He possibly just wasn’t interested in you knowing about the differences between the versions, because each time he considered his most recent version the ultimate final word on it. There’s a very nice story, which we are going to unfold a little bit in a public program around the opening, about his one big unfinished film called THE SOUL STIRRERS: BY AND BY. It was his only big documentary film project. The producer, Henry Rosenthal, whom we’ve invited to show clips, and pictures of the production process, and other unfinished materials, said he was crazy enough to start this journey with Bruce, but once he realized that the only way that Bruce could actually work was to control every single second so meticulously that it would take him weeks to produce a minute of film, he was out. If you want to do a feature-length documentary of 80 or 90 minutes or something, that is a major, major conflict.

I’ll say!

So conceptually, psychologically, but also in his practice generally, he was just not able to deal with a team, or to deal with the very idea of a feature-length film. He needed to edit and re-edit, and re-re-edit all the time. It’s that kind of obsessive quality—in his basement with his films—that really identifies his most intimate relationship with his materials.

How about the way in which they are presented? Are there stipulations around the fact that THREE SCREEN RAY, for example, can only be projected, or is there some leeway?

Well, there are some very specific conditions, and there are some variables. Stuart Comer, (MoMA’s Media and Performance Curator) and I agreed early on that we would try to show a range of different proposals rather than saying we will only show the very first original format of what was produced. So we are including film as film, and thank god Kodak has sponsored that and is still able to provide film stock—which wasn’t so clear even a few years ago. At the same time we will also show digital restorations of some films, most specifically of CROSSROADS, which will be shown as a big digital projection in the digitally restored version in the gallery, and we also want to screen cinema formats, 35mm in this case, in our theater. And then there are two works that he did for television, for David Byrne and Brian Eno, that were supposed to be shown on MTV, but never got there.

Because of copyright?

Well, yes and no. It wasn’t so clear in the end why it didn’t happen. David Byrne basically suggested that MTV wasn’t ready for this kind of work, and possibly because there were hypothetically copyright issues involved. Anyway, MEA CULPA and AMERICA IS WAITING are going to be shown on monitors, but you could certainly consider projecting them in our digital and network age. So in some cases you can sort of—not exactly do as you please—but there are variables. Although his estate tries to minimize this, some films are online, and we thought it would be good to embrace that audience. MoMA showed a movie online for two weeks as a kind of online screening, and we will do something similar, although we’re still discussing which film. The sum of that is that we actually show the range of possibilities of integrating Bruce Conner’s film and his aesthetic into different contexts, whether the gallery, online, or the cinema.

MEA CULPA, 1981. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 5 min. Courtesy Conner Family Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

AMERICA IS WAITING, 1981. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 3:30 min. Courtesy Conner Family Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Are there going to be any films at SFMOMA that weren’t shown at MoMA?

Actually they are showing one film more than we are, the Devo—

MONGOLOID.

Yes, exactly. We felt that two music videos were enough here, as we had to make some choices in terms of real estate. The important message is that for the first time his film work—have you seen the show at MoMA?

I haven’t.

That’s ok, it’s going to be even better here, don’t worry (laughs). It’s going to be the first time that his films take center-stage within the context of a museum presentation.

MONGOLOID, 1978 (still). 16mm, black and white, sound, 3:30 min. Courtesy Conner Family Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

It certainly seems that way. One of the things I like about the catalog is the number of voices and perspectives that it represents. I like that there are musicians that he worked with, like David Byrne, talking about their experiences. It’s clear that he was important to a lot of people. I was interested to hear from you whether you felt that he was himself influenced by filmmakers, particularly, because I felt like I could see Hans Richter’s influence when I was looking at BREAKAWAY and AMERICA IS WAITING. I may be wrong, but I know that he was influenced by Dada. However, the kinds of influences that he might have had don’t seem to be part of the conversation— there’s talk about Conner and popular culture, but not about art.

Well, that was a long discussion we had: To what degree did we want to establish references in art history? He was very cautious and very guarded and tried to minimize those kinds of narratives as much as he could, but then we also felt that while we wanted a lot of different voices and different perspectives, we didn’t want to go too deep into the typical art historical/curatorial narrative, but rather to emphasize different narratives. There’s no need for us to extensively analyze all of his films; Bruce Jenkins did that marvelously in the BC2000 catalog. For our part, certainly from my personal interest, there was much more emphasis on finding out what is relevant today. How do contemporary artists, for example, look at this kind of work, or respond to it? And in terms of Richter, your specific question, we can only speculate about that. What is known and documented is that he was close friends with Larry Jordan. He had close connections to many of his contemporaries in the ’50s and ’60s, so I’m sure he was very much aware of their work, but in terms of what he personally admitted to as an influence, it was more the Marx Brothers’ Duck Soup or something like that, rather than experimental film history.

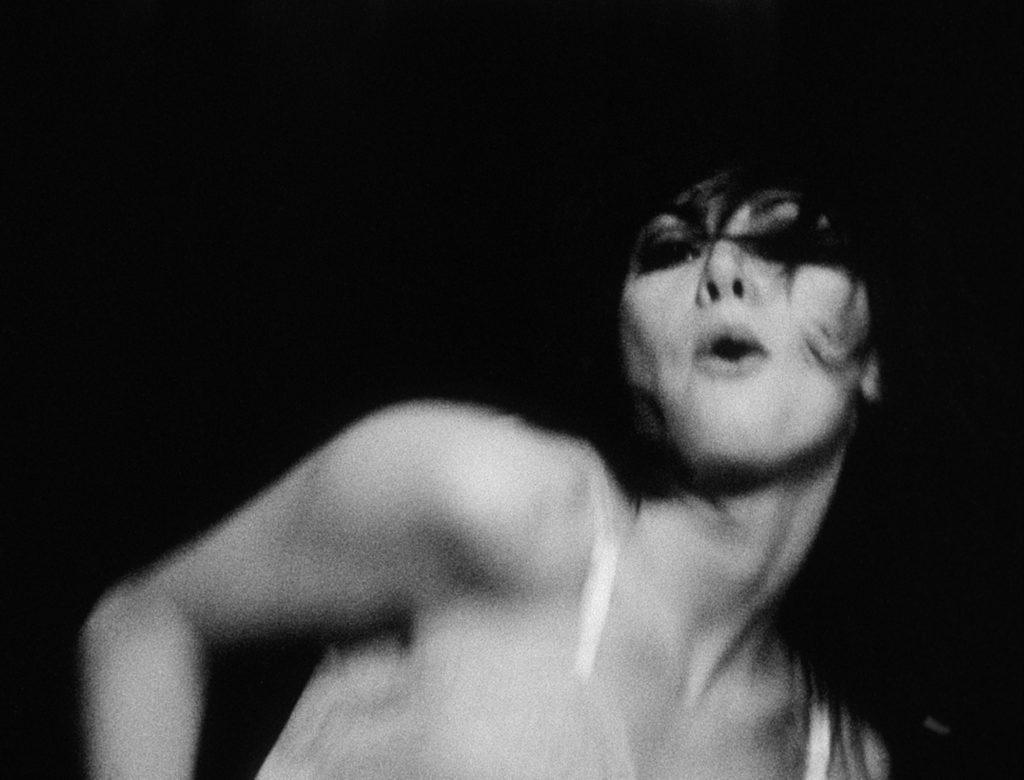

BREAKAWAY, 1966; 16mm film, black and white, sound, 5 min.; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Accessions Committee Fund purchase; © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco.

AMERICA IS WAITING, 1981. 16mm film, black and white, sound, 3:30 min. Courtesy Conner Family Trust. © 2016 Conner Family Trust, San Francisco / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Good for him. One of the anecdotes in the catalog that caught my imagination was Chris Marclay’s description of Bruce Conner attending a concert that he and Kurt Henry did back in 1980 at Club Foot in San Francisco, after which they met and then all ended up having a film and sound mixing session for one night only, which must be the stuff of legends. It must have been insanely incredible if you were there that night, but I also see Marclay’s work very differently knowing about the Conner connection.

Exactly, you can trace the links from contemporary artists to Bruce Conner, but then from Conner backwards—to Dada like you suggested, or something else—that’s much more difficult. You could probably make a film historical argument and say there are precedents and that he picked up certain strands, but that would be your personal curatorial or art historical position. As an artist I think he constantly deemphasized that trajectory and rather pointed to other directions, nineteeth century prints, for example. He wanted to project an image of himself as being very original.

Which is so contemporary or what we take for granted now: eclectic references, populism, interdisciplinarity. Back then it was a bit more extraordinary, wasn’t it?

Yes, and he was. That’s one of the theses that we’re trying to put forward—that he was such a role model in that he would not only constantly defy the very definitions of genres, he would also constantly come up with strategies to monetize his work, although he never succeeded compared to really major, commercially successful artists, but he was able to make a living more or less his entire life. In that sense, he was very much aware of himself as an artistic persona, and as someone fulfilling a role in public and having specific relationships to institutions, for example. Regarding the contemporariness of his aesthetics, one or two reviewers have said that some things look dated. I would argue they even looked dated when he produced them. He was untimely in many things he did and not in sync with the current fashion of the time. While in retrospect you would say this very idea of resistance and a sort of looking sideways and doing different things and changing course repeatedly, these are qualities that a lot of people seek in an artist today.

So in many ways he was born at exactly the right time, because he was able to function as an outsider in a way. Today he would be one of many doing this. This is sort of taken for granted.

He was also probably living in the right place for that.

That could have been just fate, or it just could have been an incredibly canny strategy that paid off a number of years later. We don’t know.

Yes. I think what we really tried to keep in mind is not to do the same thing to Conner that others have done: to label him as a funk or as a Bay Area artist, for example. It was much more important to take him out of that box. While you can say he was clearly very much shaped by it, he also shaped a series of radical movements that passed through the Bay Area, from ’50s beatnik to hippie, and also punk. Still, he never liked to be associated with these groups. He liked to be in dialogue with them, they were his friends, but he wanted to be perceived as an individual.

On this subject of friends, this is a random question, but it’s something I can’t find a definitive answer to: Subsequent to him retiring from the art world, artists called Anonymous and other names made Bruce Conner-style work, but they were not Bruce Conner. Or were they?

Well, I can’t give you an answer to that (laughs).

I see! Gary said they definitely weren’t, but other people, including his widow, seemed to imply that they were. So, it’s just something that’s mysterious and we don’t know?

Well, I think it’s part of the work that you don’t know. He has a legacy of collaborating with people, and I think he found a way to also obscure who he was, and he did that almost ever since he started. I think the first time he officially declared himself dead was in the ’60s, and so the fact that the specific relationship between these authors and himself is a question is part of what he wanted, what the effect of the work is. I want to respect that.

I find all this fascinating. I also find the images of him at work fascinating. There’s a great one at the beginning of your essay of Conner in his studio working on a hanging assemblage. You use it to discuss his theatricality, or showmanship, but my eye was caught by the mess in his studio, by the chaos. It made me think about—I’m sorry to keep throwing out art historical references—Francis Bacon’s studio, the classic, messy artist studio, and the fact that Bacon said that he needed this chaos because for him chaos breeds images.

I wouldn’t go too far with that analogy because that was a very, very early picture, and I think if you had a chance to actually go to his private home over the last decade—

You’re going to tell me it was very organized and minimal.

Yes. He was also very, very meticulous and organized, and extremely punctual.

How disappointing!

It’s a very complex personality, so again, I think as much as he could embrace change and destruction and chaos, he could go to the extreme opposite and be extremely controlling and very meticulous about the specific conditions of the materials he was working with.

So in terms of embracing change, do we know if he was excited by modernization and by the changing of the times or did he have a certain nostalgia that influenced or permeated what he was making?

First of all, I never met him in person so I can’t really speak to his personality, but from all the different stories I have heard and the accounts of people we talked to—I don’t think he was nostalgic. But he was controlling, and so it took a strong personality like Michelle Silva, his editor, to actually open his mind to the possibilities of digital non-linear editing, for example. Once he understood what he could do, he got really excited about that. At the same time, they came up with all kinds of systems. How can you reorganize a film that already has a very specific structure and basically make a triptych out of that? What are the governing principles? There were systems in place, if you want to call them that.

So here’s another speculative question for you. What would Bruce Conner make of all this right now then? Do you think he would have wanted what’s happening now? Do you think he would have welcomed it?

There’s only one comment that I can propose as an answer. When his very last film, EASTER MORNING, was shown at the Unlimited show, at Art Basel in June 2008, basically a month or so before he died, he said to Michelle, “Why did it take so long?” Meaning, why did success come so late for me. But, as I have said a number of times, he was so good at sabotaging his own success that I’m sure he would have raised hell with us for all kinds of decisions that we have taken. It’s a very delicate balance that we tried, and hopefully managed, to strike, between doing the show without the artist himself and trying to be as respectful as possible of the various comments and the guidance that his direct collaborators and his estate have given us. The way that films are presented has been developed in detailed dialogue with the estate. His wife Jean’s comments were always very, very important to us. One thing that’s for sure is that we looked at the Walker presentation of his non-retrospective BC2000, and it looked so classic that we felt that was the wrong way of doing it, and we should actually be more radical than it seems like Bruce was at that moment in his life. I’m very, very sure that he would have endlessly struggled with us about this and also because three of the most globally important museums are doing this together—the show is also traveling to the Reina Sofia in Madrid in February—and that puts a lot, a lot of pressure on things, but then again this is only speculation. Apparently at one point during organizing BC2000 the then director of the Walker, Kathy Halbreich, literally put a gun to his chest saying—

Literally?!

Metaphorically! “If you don’t treat our curators nicely from now on we’re not doing the show. Are you going to do this, yes or no?” It came to that point. Actually we have had a much different experience and it was a very, very collaborative and generous process with everybody involved.