Cecily Brown: Rehearsal

The Drawing Center

35 Wooster St. New York, NY 10013

October 1 – December 15

“The word ‘rehearsal,’ as derived from the Old French rechercier, originally meant to go over something again with the aim of understanding or mastering it,” states the press release for artist Cecily Brown’s current exhibition—Cecily Brown: Rehearsal—at The Drawing Center in New York.

However, when entering the gallery space—thrust into a baby-pink and forest-green world of Brown’s eighty-plus gestural drawings ranging in size and subject matter (there’s a petite row of Goya-inspired sketches, a corner of gouaches based on the album cover of Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, and spread of the artist’s beloved animal pieces, taking reference from animal encyclopedias)—I couldn’t help but feel like Brown reached mastery long before the work was made and the show was hung. This feeling of mastery derives not only from the artist’s obvious (normative) skill—her ability to replicate the renderings of Old Masters (e.g. Bruegel, Rubens, Poussin, and William Hogarth), reimagining features of their works as fragments in her own pieces (such as a detail of a Bosch nymph finding a home next to the chiseled bodies of Degas’ Young Spartans Exercising or a Knox Martin goat)—but also the sense of fluidity and playfulness that seems to pervade her efforts.

Cecily Brown, Untitled (After Bosch and Boldini), 2015. Watercolor and pastel on paper, 79 x 51 1/2 inches.

Brown’s work feels both jovial and apocalyptic. For example, in the 2015 piece Untitled (After Bosch and Boldini), a wispy magenta plane created by rapid lateral brushstrokes grounds an orb of disjointed birds and figures—beaks, eyes, tail feathers, and corporeal contours—folding in on each other. Surrounding this action lies a collection of smudges (the residue of Brown’s dirty hands, an almost Lascauxian index of her presence). These tactile handprints coupled with the tumultuous imagery then seems to move Brown’s discussion of genealogies and lineages from a conversation about art history and culture—about Bosch and Boldini—to the realm of the personal, an individual (yet social/cultural) confrontation with a sense deep past, or the primordial.

That being said, Brown’s work is wholly of this moment. Many of the birds are rendered in yellow crayon. She interprets the curvature of a Boldini nude as a turquoise squiggle. And, the composite of imagery itself seems to tap into a postmodern, post-Internet, post-Photoshop sensibly of multiplicity and heterogeneity. This use of color, gesture, and simultaneity then negate any inkling of melancholy or the belated on the artist’s behalf. The past is simply another element for Brown to play with—a fertile but single constituent in her larger inquiry into representation and expression.

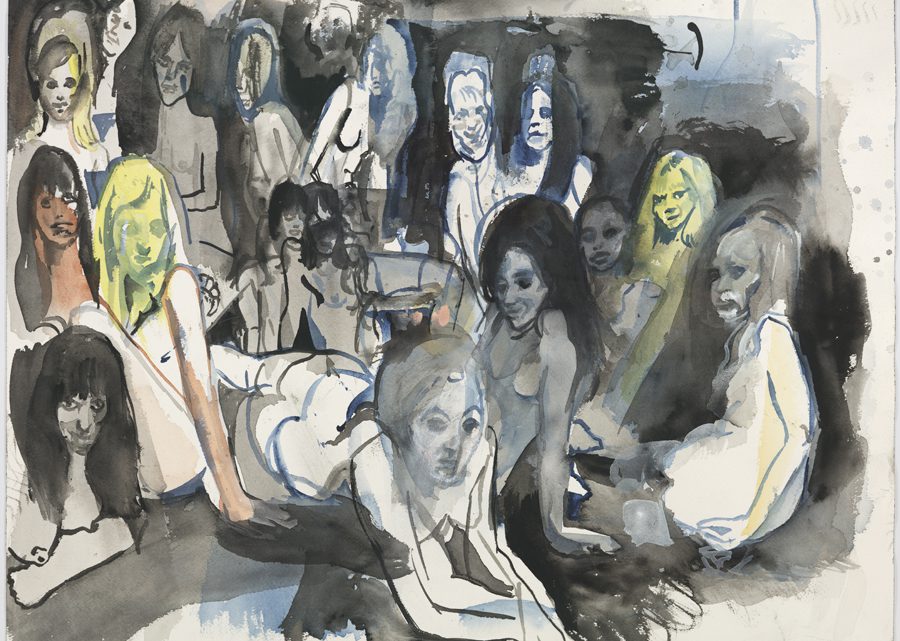

Cecily Brown, Untitled (Paradise), 2014. Watercolor, ink, and ballpoint pen on paper, 14 1/8 by 20 1/8 inches.

Brown has something to say.

And, it is precisely this sense of saying something that relates back to rehearsal.

For me, Brown’s drawings always dredge up the image of a dog digging for a lost bone, hole after hole with no avail.

This is not to say that the artist’s work is misdirected. In fact, it is the opposite.

Brown’s drawings are characterized not solely by action (by gesture, expression, and gesticulation) but by perpetuity. And this constancy reveals itself not through simple repetition, but reframing. For example, the motif of Goya’s clasped hands that occurs in an untitled drawing from 2000 reappears 15 years later in Untitled (After Bosch). It is this clashing of imagery between pieces and over time that gives the viewer the sense that the artist is not only looking for something, but something in particular—that Brown is not only composing statements, but asking pointed questions.

Cecily Brown, Untitled (Chambre), 2015. Pastel on paper,

47 1/4 x 35 inches.

The exhibition layout furthers this impression. The show is divided into roughly nine sections: Stage right of the entrance is a series of black-and-white pen drawings with hot pink accents done “after Goya.” To the left of these sketches hangs Untitled (Chambre) (2015), a bloody-colored work, which feeds into a collection of peachy watercolors inspired by Jeux de Dames Cruelles. These graphic images then lead into a section of sensuous warm-palleted Electric Ladylands, followed by a selection of cool-palleted works. Adjacent to this slate spread, on the back wall hangs an array of ink drawings based largely in Bruegel. And, in front of these pieces on a separate table stands some of Brown’s own monochrome sketchbooks. Pivoting 90 degrees to the right are her “after Hogarths.” These bright watercolors then flow into the fauvist animal drawings, which eventually loop back to the Goyas.

Cecily Brown, Strolling Actresses, 2015. Watercolor and ink on paper. 52 1/2 by 79 inches.

The layout then not only imposes an esoteric cyclicality on Brown’s project—a looping ordering of color and subject take takes on its meaning through the viewer’s procession through the space—but also discloses her process of going over. The weighted motifs reveal themselves as subject to evolution and adaptation not only in the individual groupings but also within the entire body of work. For example, a gap-mouthed fish central to Brown’s animal inquiry manages to weasel its way into a large number of non-animal focused pieces. This slippage of imagery then communicates a merging of melting of worlds, of temporarily—of eras, of time zones.

However, this slippage is not dreamlike—but rigorous.

When viewed as a whole, one gets the sense that the motifs in Brown’s drawings are not just images but fragments of an archeological puzzle. And that through a tireless effort of swapping and rearranging these tiles, the artist is undergoing a relentless trial of not only mining the conceptual shape and bearing of the elements but also trying to find her own timeless composition in an unfathomably long lineage.

It is then this act of mining and probing that makes Brown the master of her own rehearsal.