Becky Evans: Waterlines

Piante Gallery

620 2nd St, Eureka, CA

October 1 – November 12, 2016

Viewers who enter Becky Evans’s new exhibition at Piante are first confronted with Turf Spiral—a roll of industrial sod coiled like a garden hose in the middle of gallery space, as if ready to be unspooled. Its function seems talismanic. It’s the largest artwork in the exhibition—and the only one that documents a state of being rather than a process. This is “nature” stretched thin to the point of transparency: a monoculture product, grass selected across generations for toughness and uniformity, spooled on a reel for convenience.

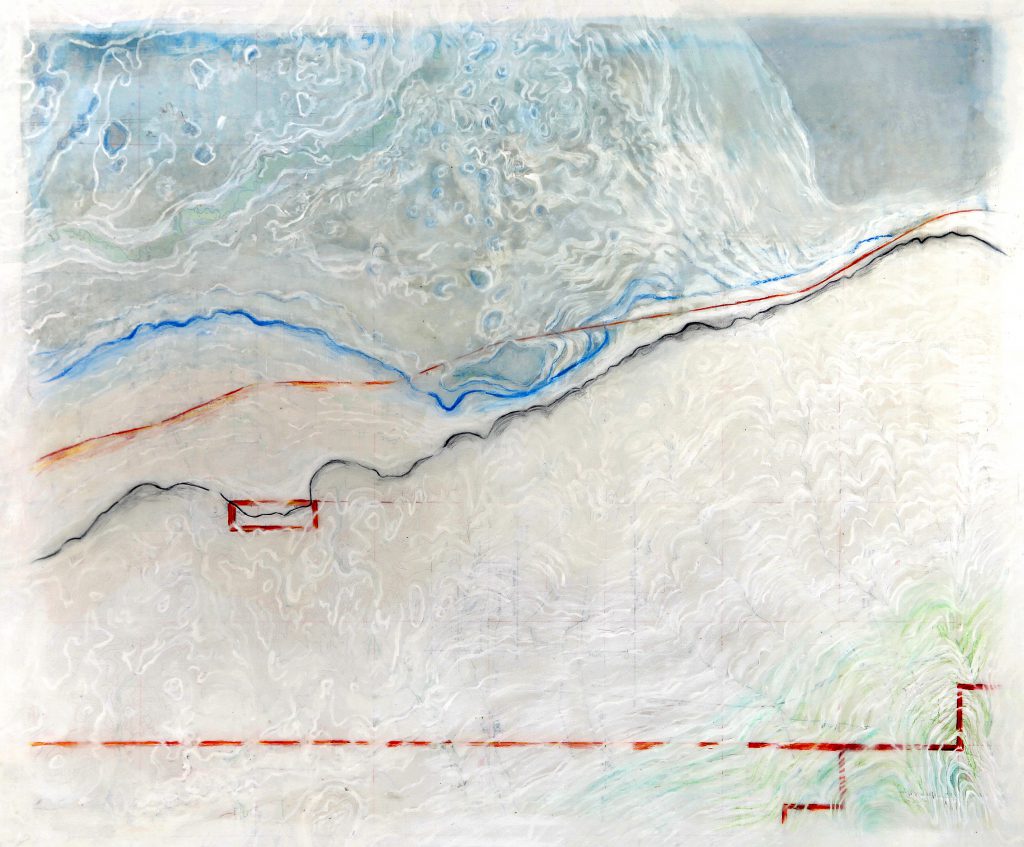

Becky Evans, Basin of Subsidence-San Joaquin Valley, 2016. Photo credit: Joseph Wilhelm

Other artworks lend visible form to ecological processes. Subsidence – San Joaquin Valley (2016) is a basin made of papier mâché and mud that rises from a central declivity in a series of plateaus, each contour line corresponding to the shape of a progressively shrinking aquifer. The unpainted porcelain olla vessels titled Maps of Subsidence from Merced to Delano (2016) repeat ceramic forms with a long history of use among indigenous Californians. If the fine lines Evans incises on them look vaguely familiar, there’s good reason for that: they map real channels along which water and bodies continuously flow. Some of these channels, like Interstate 5 and the California Aqueduct, are visible to the naked eye; many major irrigation pipelines are not. Encaustic paintings hung on the exhibition walls depict the surfaces of dry lakebeds. In these pictures, detailed vignettes of parched surfaces are surrounded by a peripheral haze that makes the scenes feel intimately embodied because it simulates the effect of so-called foveal vision; in other words, the paintings’ visual fields are characterized by a single point of sharp focus with a corona of softer-focus information surrounding it. This is how human vision actually works. But it’s a reality that is almost always elided in the representations we make of the world viewed. Evans’s paintings are outliers because they repeat visual experience the way it’s lived moment-to-moment, rather than the way we tend to reconstruct it after the fact.

Becky Evans, Maps of Subsidence from Merced to Delano, 2016. Photo credit: Joseph Wilhelm

Evans, who is originally from the Los Angeles area, resides in Humboldt County in northern California. She has been making art that responds to the western landscape for years now, using a witchy and evocative roster of foraged materials like alfalfa, madrone, and lakebed clay to document natural and human-made change. Her 2013 series of re-imagined maps visualized how the Klamath River watershed would expand if the dams and diversions currently impeding its flow were removed, and a 2015 prayer rug reunited shattered fragments of clay from the bottom of Oregon’s alkali Summer Lake.

Becky Evans, Dry Lake – Prayer Rug for Climate Change, 2015. Fired lake mud. Courtesy the artist.

This exhibition takes a conceptual turn out of necessity. Most of the artworks document events that remain not only unseen but also un-seeable, like the drying up of lakes and the exhaustion of aquifers. They visualize the subsidence that has become endemic to arid Western states, as groundwater reserves get exhausted by burgeoning demand. Maximum subsidence levels have been reported in the San Joaquin Valley, where pumping millions of gallons of groundwater to irrigate crops on an industrial scale for more than a century has made the land sink as much as 25 feet in places. Subsidence happens underground, in the dark; people can’t see it, which might be why it exerts scant pull on the public imagination relative to other, more visible manifestations of ecosystem change. Evans aims to change that by creating art that makes the unseen visible, and therefore thinkable.

Her work has a tough-minded, data-driven slant: even pieces that involve the most fragile and esoteric naturally sourced materials turn out to be pregnant with information. An unfired ceramic piece like Subsidence – San Joaquin Valley is unbothered by aspirations to transcendence. Shapes correspond to real coordinates; contours are often occult, but never random. Nothing is arbitrary, and everything is interconnected. The impulse behind the work seems to be anti-monumental; rather than commemorating an enduring state, it chronicles change.

Installation view of Becky Evans: Waterlines, Piante Gallery, 2016.

Since colonization, attitudes towards land and water in the American West have been presaged on a resource extraction mentality informed by an exceedingly simple notion of entitlement: “There it is, take it,” as William Mulholland famously told the public in 1913 when he pulled the lever that sent water splashing through an aqueduct from the Owens River to the San Fernando Valley, initiating the history of modern Los Angeles. This no longer seems adequate as a rationale, given that a lot has happened in the hundred years since. Overtaxed resources have dwindled; rivers now run dry on a regular basis. Most people of Mulholland’s day understood forests, watersheds, and mountainsides first and foremost as under-potentialized reservoirs of profit; those same sites are now understood to exist as complexly and reciprocally interconnected systems that are all too finite and irreplaceable, once gone. Evans’s artworks memorably document the systemic, integration of the natural world, and her approach suggests that the integrated world can best be served by not resorting to the default Western view that posits groves and brooks as vessels to be charged with meaning. When gnarled madrone branches or mandolin-cut potato slices appear in one of Evans’s installations, nothing about these materials suggests the emblem-assignation process in which, say, felt is meant to equal insulating warmth, while honey indicates social harmony. Evans’s sticks and stones prompt lateral connections rather than gesturing to some concept writ large. Because these materials reveal the traces of the unseen forces that shaped them, they become apparent not as monads but as excised nodes.

Becky Evans, Owens Lake, from Lone Pine, 2013. Altered USGS map, watercolor, inks, colored pencil. Mounted on panel under beeswax. Courtesy the artist.

It’s possible to think about the reshaping of the continent’s western water supply as an earthwork of historic proportions. After all, an author who may or may not have been Marcel Duchamp published a brief 1917 defense of the readymade Fountain that closed with the riposte: “The only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.” This might have been intended as a sick burn, but it becomes funny because it might in some sense be construed as true—at least in the West, where wholesale reconfiguration of the water supply created the wealth that sustains the region’s artworld outposts. Modern Californian history is founded on the unseen flow of waters underground. This is true in the sense that both the southern California population boom and the billion-dollar agribusiness of the state’s Central Valley depend on groundwater pumping and large-scale diversion of river water from the relatively verdant, depopulated north to the state’s fertile but arid center. The 20th century reshaping of the water supply cannot be overestimated as a force of modern change. Like the work of fellow Californian artists Amy Balkin, Cynthia Hooper, Josef Jacques, and Emily Silver, Evans’s artworks give us a way to visualize that principle in action.

The works of art in Waterlines bring unseen things into haunting, sometimes disturbing view. They do not build confidence; what they express has to do with the limitations of what’s humanly possible, which makes them all the more worthwhile. Evans undertakes something difficult but consequential in seeking to lend memorable form to such phenomena.

Becky Evans, Subsidence Mesa Arizona, 2016. Photo credit: Joseph Wilhelm