Kour Pour is a Los Angeles-based artist. Our conversation started via DM on Instagram while Pour was in Berlin and was then followed by a series of emails, phone calls, and studio visits back in LA. I was curious to find out more about his new series of artworks that he displayed in New York at Feuer/Mesler and Berlin at Gnyp Gallery this past spring. The first part of this interview focuses on Pour’s newer works where we discuss formal qualities, process, and history. The second part of the conversation focuses more on the ideas and experiences behind Pour’s practice as a whole. We move in and out of his carpet works, to his ukiyo-e inspired paintings, to his work with paper and his “ready-made” platforms. Other topics discussed include sushi, the 1970s Pattern and Decoration movement and cross-dressing kabuki actors.

You’ve just returned from two solo shows that you presented in both Berlin and New York City where you exhibited new paintings that reference ukiyo-e prints and Japanese landscapes. The works also look very different from your previous series of carpet paintings. Could you explain how you arrived at this new series?

I see the new work as a study of Japonisme, the influence of Japanese art and aesthetics on Western culture. For me these new paintings are another exploration into cultural exchange, similar to the way my carpet paintings traced a history of early trade and exchange by depicting imagery and design influenced by different cultures. I got really into Japanese ukiyo-e prints by looking at Western art history and how big of a role ukiyo-e played in the beginnings of modern art. The impressionists used many characteristics from ukiyo-e prints such as pictorial cropping and clean contours. I wanted to explore this exchange between Japan and the West and started experimenting with the printing process used to create ukiyo-e prints. I then came across these Japanese Geological Survey maps that look very much like abstract paintings from Europe and America, painters like Clyfford Still, Helen Frankenthaler, Nicolas de Stael, Serge Poliakoff, and the camouflage paintings by Andy Warhol. Since the Japanese landscape was a main theme in ukiyo-e, the maps were a natural subject to take on. I started creating these paintings that have the appearance of what I think of as Western abstraction, but using both a process and subject matter associated with Japan. I think the conversation became a lot about authorship, location, and displacement.

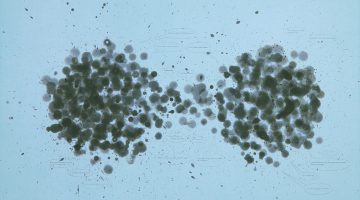

Process photograph taken at Kour Pour’s studio in Inglewood, California, 2015. Courtesy of the artist.

Andy Warhol, Camouflage, 1986. Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on canvas., 40 x 40 inches. Courtesy of the Internet.

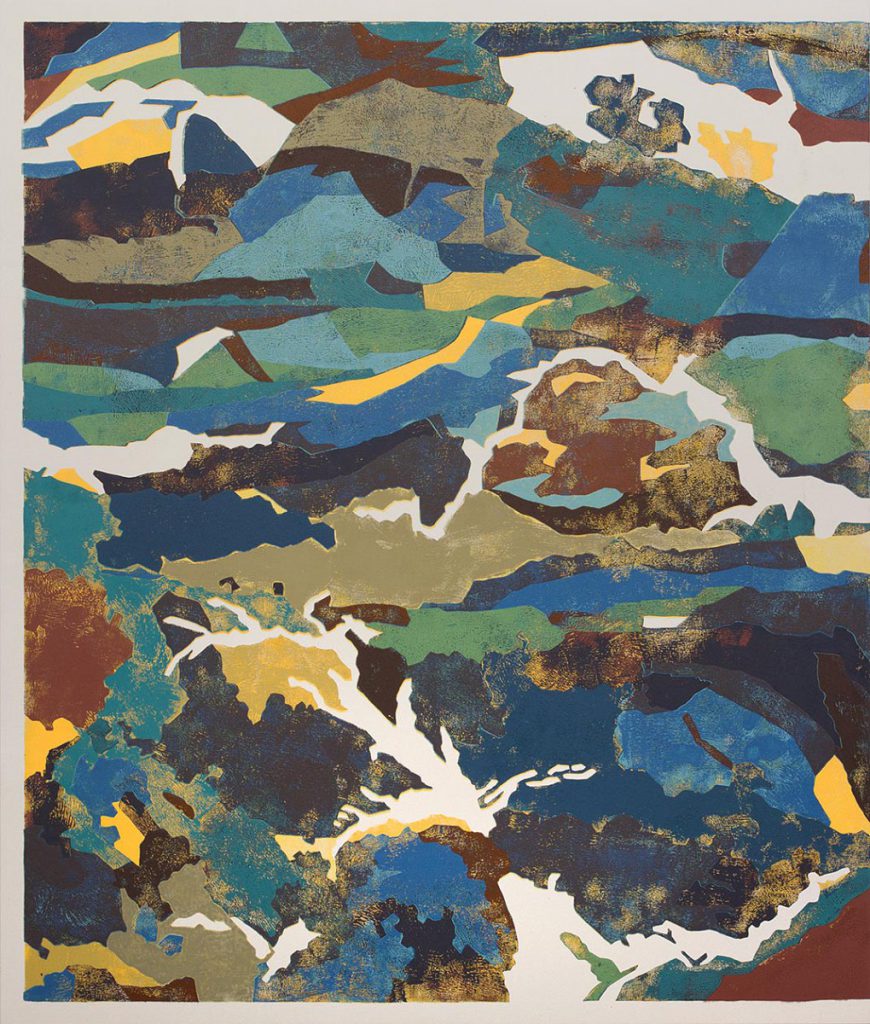

California Roll, 2015. Block printing ink on canvas, 87.5 x 71.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Now before we get into the important discussion of authorship, location, and displacement, perhaps we can start the first part of this conversation talking directly about the works. Can you formally discuss how your new work visually relates to the abstract artists you mentioned?

Well, for starters, the maps that I use as reference material already look visually similar to abstract paintings with their big blocks of color and a mix of both geometric and more amorphous forms. Ukiyo-e prints are made on paper and are generally small and intimate in scale, but I wanted to blow the maps up in size and print them onto large raw canvas to reference the grand scale and history of abstract painting. Another detail is that, due to the multi-layer printing process, you can see the different layers of color popping through the surface, almost like a pointillist or color field painting. I also use color palettes in some of the paintings that are probably more of what you could expect from a Western aesthetic. Basically any of the formal choices that I made were to reference some aspect of abstract painting from a European or American history.

You said that you experimented with the printing process used to create ukiyo-e prints. Can you talk more about this process and how you used or altered it to create your paintings?

The printing process is called moku-hanga. Traditional ukiyo-e prints are printed at a small scale on paper, so they are very fine, flat, and accurately printed. My paintings have a completely different surface because of the large scale; they’re super-sized.

My first step is to project and trace the images of the geological maps onto sheets of vinyl, which are then laid down onto wooden platforms with industrial tape. Only one color can be printed per day. Ink is rolled onto the block, and then the canvas, which is attached to a jig system on hinges, is lowered to the platform and hand-printed with a baren, which is a small disc-shaped printmaking tool. The process is slow. Every day that we print a new color, sections of the vinyl are cut and removed from the block. For a printing process the results are quite direct and painterly. The ink can be applied thicker or thinner in sections, there is the texture left by the ink rollers and the jig can shift so the shapes register differently with each print. The weather also plays a big role because if it’s hot out, the ink doesn’t want to print as well as when it’s cooler, so there are a lot of variables that you can’t control and you never know how each color will look. It’s also a pretty physical activity, because of the scale of the paintings, so my assistant Errol Sabinano and I literally have to crawl on top of the canvas to apply pressure with the hand barens, which causes the surface to crack and shift. Sometimes you can see traces of our palms and knees on the surface of the painting too, which I quite like.

Rising Sun (Pacific Ocean), 2015. Block printing ink on canvas, 83 x 69 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

Katsushika Hokusai, Fine Wind, Clear Morning, 1830-32. Ukiyo-e woodblock print. Courtesy of the Internet.

It appears to be a rigorous and controlled process, but, in fact, it’s quite precarious at times. I love how you are deploying this somewhat old mechanical reproduction machine, but the artist’s or assistant’s hand is embedded in the work. All that said, I want to return to the very wooden platforms that you use in the creation of the paintings. You displayed them as finished artworks in New York and Berlin.

Because we have to hose down and wash the ink off the platforms everyday, the wooden panels starts to warp and peel over time. After several months the panels need replacing, and the first time we did this we leaned the used platform against the wall and had kind of a moment with it. The platform was covered in ink stains, blade marks from cutting and removing the vinyl, tape residue, and anything else embedded in the layers of shellac that we apply to protect the panel from water damage. It was like looking at a diary of the past year of work. I decided to include them in the show. They seemed really important and not because they show how the paintings are made, but more so because they are something that would usually be disregarded even though they are so integral to the entire process. They are the record of labor, which is usually invisible and I wanted to give worth and weight to the disposable and the ephemeral.

Installation view, Onnagata at Feuer/Mesler, New York, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

The discussion of these platforms leads me to another interesting series of work: the ones made from paper. I think these are a critique of modernism—and especially Greenbergian modernism—given the “painting” isn’t just about painting—you use paper pulp. I also think of ephemera. I know papermaking is more of an Eastern tradition, so does this in some way infect the history of modernist painting?

Yes, you’re right about the papermaking tradition and I looked specifically at origami, and the lesser-known tsugigami, both Japanese paper crafts. In fact, I like that paper is thought of as a craft material, it’s usually more ornamental and delicate. Artists make works on paper as sketches or as secondary to works on canvas; paper has the value of a lesser material. I started to experiment with paper making in the studio, not really knowing what I would do with it. I shredded and mixed pulp out of newspapers that I collected from the markets and delis that I frequent close to my studio in Inglewood. I started dying the pulp with ink, which introduced color. I could work and form the pulp with my hands and feet; it’s quite a therapeutic activity. After playing for a while I started producing large sheets of paper pulp, around five-and-a-half by four-and-a-half feet, and mounted them onto panels that were stretched over with linen. I would then lay these linen panels outside in the parking lot and start throwing down wet sheets of pulp. There is very little control in the process and it’s all very similar to action painting that way. The results are these very visceral paintings, very minimal in color with a lot of physical depth, texture and folds. They are the most painterly works that I’ve made so far and I really love how direct they are—paper on linen.

I think what’s interesting is that you’re making these different bodies of work that all have different aesthetics and yet there seems to be a line that connects them all. I’m specifically thinking of how the paper works, and even the new ukiyo-e influenced paintings, relate to what you were doing in your previous work where you referenced Asian carpets and weaving. I feel like there is a discussion of the 1970s Pattern and Decoration movement with what you’re doing and how your work relates to ideas of craft, labor, beauty, and feminism—as well as identity and cultural authenticity.

All the different things that I reference seem to have a commonality, which is that they are based in a specific culture, history, or location, so before I even start the work it’s already embedded in these kinds of discussions. Carpet weaving is historically attributed to tribal and nomadic women’s work, delicate papermaking is an Asian tradition, and ukiyo-e is located in Japan and made cheaply as posters for the masses. These are all ideas that I’m interested in, and I try to transform them or tweak them in a way to experience their value differently, or at least to try to confuse their inherent identity.

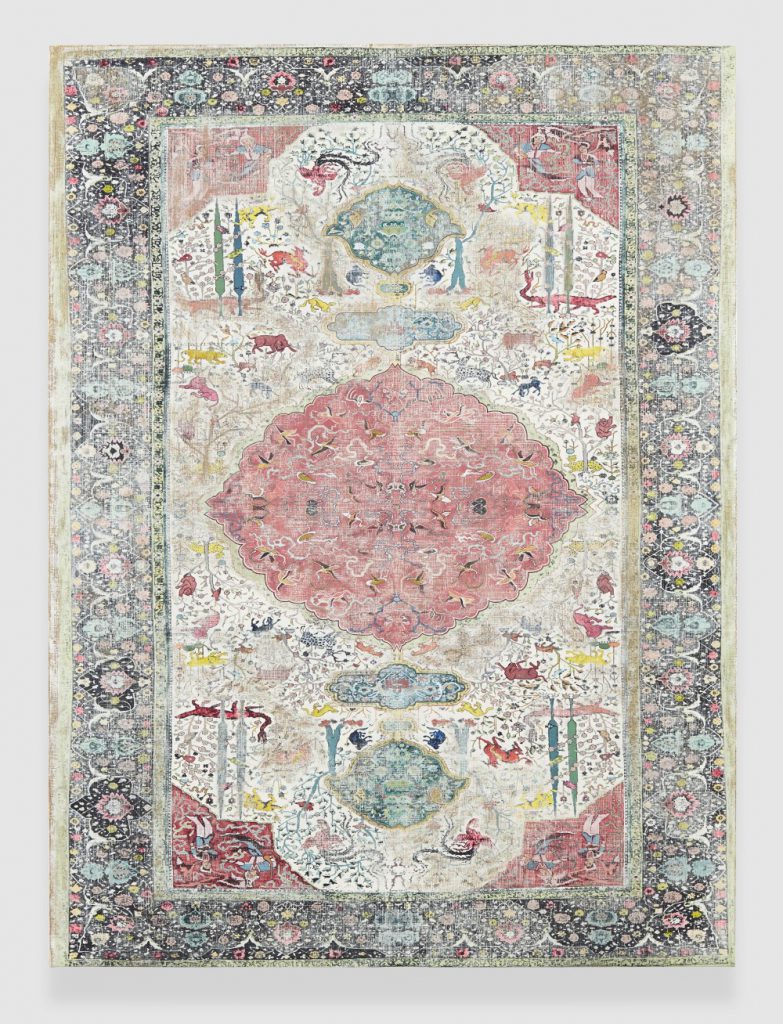

With the carpet paintings, I literally translate an image of a carpet into a painted work on canvas. I’m not weaving but painting, and more in the tradition of miniature painting, so the process almost mimics weaving with all the small brushstrokes and careful line work. I wanted to transform the object in a way, or in a manner, that would cause the viewer to question why I would bother reproducing a carpet as a painting. Also, metaphorically, taking a carpet from the floor and putting it up on the wall with the rest of the art is a pretty direct statement about exclusion and value. There is also a conversation about how flatness and geometric forms from the decorative arts moved their way into modernist painting, which is extensively written about in Joseph Masheck’s book The Carpet Paradigm.

Similar things happen with the newer paper and printmaking works. Their material and process is used in a slightly different way, in a way that references Western art. Or I guess depending on who’s looking at it, the works could be thought of as Western art, used in a way that references more Eastern art forms.

Dragons & Genies, 2012-2013. Acrylic on canvas over panel, 96 x 72 inches. Courtesy of the artist.

That’s an interesting point you bring up and something that your work makes me think of: the viewer. Because your references are so varied I can’t help but think about who and where your art is being viewed and how the meanings will change based on these factors.

I’m glad you brought that up because I spend a lot of time thinking about the viewer. I know as an artist, I’m not supposed to care about the viewer or audience; I’m supposed to just do whatever I want. For me, the viewer is as important as the artist. Meaning is always co-produced—there’s a producer and a consumer, and each is bringing their own references to a work. This is especially true with my work due to the fact that I reference and appropriate almost everything that I make. I think we need to put more emphasis on who’s viewing the work, or who’s writing, curating, or reviewing art. If my identity is used as a point of reference to help explain or better understand my artwork then shouldn’t it be the same for the person writing about it or showing it? Isn’t their frame of reference a source of bias, just as mine is seen as a source of inspiration? We have identity politics for artists, but what about for curators, dealers, and writers? I think that’s something we really need to look closer at because that’s where a lot of the power lies in how art is disseminated, read, and valued.

Installation view, Onnagata at Feuer/Mesler, New York, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

I wonder if we can talk more about how ukiyo-e prints ended up in European hands. I’m thinking about the vehicles of exchange here, how culture is spread across time and location—for example, trade, which has its “dark sides.”

Ukiyo-e prints arrived in Europe during the Japanese Meiji government’s “modernization” period, although some labeled it as the “westernization” period. Borders were opened up in Japan and Europeans began trade. Ukiyo-e prints and other Japanese arts were exported and made up 10% of the country’s national income at the time, so as you can imagine, many prints were produced. Of course, these prints ended up in the hands of artists like Manet, Gauguin, and Van Gogh and had a heavy influence on their works. Van Gogh wrote about Japanese art often in his letters. Likewise, Japanese art became influenced by contact with Europe and ukiyo-e prints started to include Westerners in European dress. Japanese painters also started producing paintings in the impressionist style—although these artists were disregarded and labeled as inauthentic, their paintings didn’t look “Japanese” enough to Westerners. There were many political and economical reasons that sparked this particular example of cultural exchange and it was interesting to see how they affected artists and art making.

Does this experience of movement have some connection to your own biography? I know you grew up in England and then moved to Los Angeles. You also have part British and part Iranian ethnicity. Can we perhaps talk about your practice as being diasporic? You previously mentioned displacement when discussing your paintings, what did you mean about this more specifically? I do not mean to conflate the artist with the artwork, but there seems to be a thread here.

Yeah, it’s fair to say that all these interests stem from my own movement in life. I think my entire practice is based on my personal experiences of living in different countries, having multiple identities and exposure to different cultures. It’s about my experience of being displaced. But there’s so much movement in the world, and I’m pretty sure that most of the population has shifted from one location to another, locally or globally, so I think we have all experienced displacement in one form or another. So things change and identities shift. For example, I love Japanese food: sushi, ramen, tempura, etc. I didn’t know this until recently, but tempura was a Portuguese export. It has become such a staple in Japanese cuisine that the history and origin is forgotten and disregarded, or perhaps just became unimportant. And then you have things like the California roll, where the nori, or seaweed, is rolled inside-out because Americans were originally put off by the sight of it on the outside of the roll. These are the kinds of experiences that influence my practice and that’s why you see a rug as a painting, or images placed in a space where they don’t belong, or an abstract painting made as a Japanese print.

One other thing that I’ve noticed is that up to now, your work has always been somewhat historical. I think the discussions around your practice are quite current and topical, so how come we have only seen references to the past and not the present in your work?

When you start any new project, don’t you always begin with research? And research happens by looking at the past. So, I’m looking at how we have arrived at the present, to try to better understand all this craziness and confusion. But I can definitely see myself referencing the present in future works more directly. What would be the point of all this research if I wasn’t interested in the present and the future? My studio is right next to LAX airport so I see all the planes and people coming in and out on a daily basis. I think about what they may be bringing with them, or what they are taking away. I’ve been doing more travelling myself lately, especially with the two shows where I simultaneously showed the same series of works in different locations. It was interesting to have very different conversations in both cities about the shows and it goes back to what we talked about with viewership and the co-creation of meaning. This experience of cultural exchange is a constant in my life, who and how we influence each other, not just in the past but now.

Thank you for these insights, Kour. But, one thing we have not discussed yet is the title of your exhibition: Onnagata—which I think you should define and elaborate on. This seems to have something to do with what you mentioned about identity and appearance earlier.

Onnagata are the male actors who play female roles in Japanese kabuki theater. I came across them as they are often depicted in ukiyo-e prints dressed in kimonos and headdresses and covered in makeup; some are really over-the-top and quite comical. I thought that my works shared a relationship with the onnagata since I am also playing with the “identity” of the paintings through the appearance of the painting’s surface. This dressing up had me thinking about identity in the context of theater with actors playing roles; this seemed to highlight the way we associate identity with more superficial things like appearance in real life. I think that because we are such an image-based society, especially with social media, appearance has become even more representative of identity than ever before.

Now, your discussion on onnagata is very interesting to me, given that I work with gender and sexuality in my work on art and visual culture. Also, as some may know the same “playing out” of gender took place in Elizabethan theater: men playing the roles of men and women. It is interesting that we have two distinct cultures enacting what we now call “cross-dressing”—and without either culture knowing the other was doing it. A lot can be said about this: one being the way gender is a performance—an art, if you will.

Yeah I’m definitely interested in how appearance, or performance as you say, plays a big role in identity construction. I thought about this a lot when I started my carpet paintings, you know, what it means to paint Persian carpets when I have Iranian heritage, I knew people would relate the work to my cultural history. There’s no escaping that. The personal is still really important to me, but there are so many things about a carpet as an object that interested me beyond my own cultural representation. Appearance and representation is a conversation in my work now, especially with the new paintings that are referencing specific histories. In a way I’m using appearance to represent a certain identity, but then I want to try to confuse it so it isn’t as straightforward or surface based.

As we can tell based on this conversation, nothing is straightforward or simple. You have not forgotten the complexities of post-colonialism and postmodernism, and you have shown how the past influences the future, as well as how the present influences the past. This leaves me, and I am sure others, with a much more profound understanding of your work. Now, I would like to offer my thanks to you Kour, for your time, energy, and patience.

Thank you Robert.