From mid-century Hollywood to the millennial megacity that stands today, Los Angeles has long helped to fashion a global sense of what it means to have style. A regular column in AQ, Style Wars aims to appreciate how critical considerations of “style” can offer opportunities to think across sets of subjectivities and cultural practices that are often disassociated or pitted against one another. On the occasion of LXAQ, guest contributor Martha Kenney responds to this challenge by asking readers to turn their attention towards the City of Angels’ literal atmosphere. She reflects on the ways that contemporary arts practice, the fight for environmental justice, new media economies, and styles of citation and information sharing all become entangled through critical considerations of smog. Unsatisfied with the hazy modes of reporting and thinking that have become all too characteristic of present-day society, Kenney suggests that more particular and situated modes of information sharing and gathering are required if the current information age might serve to address the historical inequities that mark each of our everyday lives in myriad ways.

—Nicole Archer, Column Editor

***

Air pollution is central to the Los Angeles imaginary. A perpetual haze hangs over the sprawling cityscape; we breathe it into our lungs in ongoing, corporeal penance for an urban infrastructure designed only for automobiles, for a car culture now so naturalized it seems like culture itself. Smog isn’t only an LA aesthetic; it also enacts a spatial politics. The location of pollution sources and the direction of air currents conspire to create an uneven geography of respiration; some breathe cleaner air than others.

PigeonBlog

Artist Beatriz da Costa created PigeonBlog (2006-2008) as a response to the politics of smog. In LA and elsewhere in the United States, urban air pollution is measured via fixed monitoring stations located in low traffic areas, away from proximate sources of air pollution such as power plants, highways, factories, and refineries.1 While these stations are good for monitoring average air pollution in a given city, no comparable data is collected for high traffic areas—neighborhoods near industrial sites like oil refineries that are often home to a disproportionate number of low income people of color. The environmental justice question of who suffers most from air pollution is foreclosed by the standard method of monitoring.

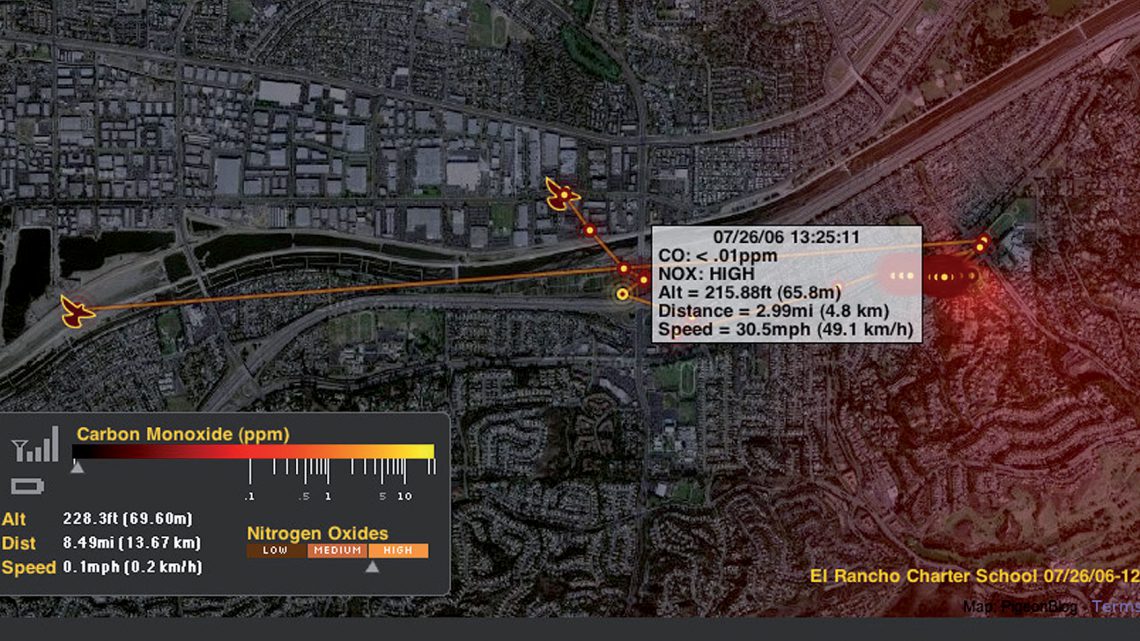

To address this problem da Costa enlisted an unlikely ally: homing pigeons. For PigeonBlog, a flock of homing pigeons were fitted with pollution sensing “backpacks” that transmitted pollution and location data. The data was mapped in real time onto the PigeonBlog website, creating a “heat map” of local concentrations of air pollution.2 Flocks of pigeon-pollution-bloggers were released three times in Irvine and San Jose, garnering positive press in the international news media.3 The releases also had some unintended consequences: PigeonBlog was protested by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and courted by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).4 Because it was unexpected and charismatic, PigeonBlog caused a stir; people in art, science, engineering, and animal worlds took notice and many scholars, myself included, continue to teach PigeonBlog in our classes.

Beatriz da Costa died of cancer in 2012. However, PigeonBlog remains an important intervention into the aesthetics and politics of air pollution and its measurement. As scholar Kavita Philip argues, art projects like this that bring together unlikely actors (pigeons, artists, engineers, pigeon fanciers) around an urgent environmental health problem offer “collective forms of resistance to the neoliberal systems that accelerate scales of immiseration and render large portions of the earth uninhabitable.”5 In an era when environmental regulation is met with ongoing, well-funded resistance from multi-national corporations, PigeonBlog provides a brief glimpse of another world—a world where we don’t entrust environmental monitoring and regulation only to government actors, but rather to flocks of pollution-sensing pigeons that traverse the sky, gathering data to protect those who breathe air polluted by industries that profit at their expense.

Beatriz da Costa and some of her pigeons. Courtesy of the artist and MIT.

Pigeon Air Patrol

Given the media attention that PigeonBlog received, I was surprised to hear in March 2016 about a new project that was being described as “the first ever flock of pollution monitoring pigeons.”6 The Guardian was the first to report the launch of Pigeon Air Patrol: a flock of racing pigeons flying above London, wearing pollution sensors (also called “backpacks”) and sharing their data over Twitter.7 Although superficially similar to PigeonBlog, this project was not an art installation nor a “grassroots scientific data gathering initiative,” but a marketing stunt.8 Pigeon Air Patrol was created by Pierre Duquesnoy, Creative Director of DigitasLBi, “a global marketing and technology agency that transforms brands for the digital age.”9 The purpose of Pigeon Air Patrol was to promote Plume Air Report—an app that forecasts air pollution.

After the original article in the Guardian, the story spread quickly; over 2000 stories about Pigeon Air Patrol ran in news outlets around the world, generating free publicity for DigitasLBi and Plume Labs, their client.10 Most of these stories did not contain any additional research beyond what was reported in the original article. There was no mention of PigeonBlog as an important predecessor, nor any real discussion of Pigeon Air Patrol as marketing rather than art, technological innovation, or activism.11 The media almost unilaterally presented Pigeon Air Patrol as a fun, innovative, and socially-conscious project.

However, if you compare the aims of PigeonBlog to those of the app that DigitasLBi is promoting, a different impression emerges. Whereas da Costa was concerned with social justice and the unequal effects of urban air pollution, the Plume Air Report app individualizes the problem of air pollution, telling users whether or not it’s a good time to go for a jog or dine outdoors. For many people who live near highways or refineries, exposure to pollution isn’t a matter of optimizing one’s lifestyle (should I take a jog now or in a couple of hours?) but an everyday necessity (I have to wait for the bus every day at 6 a.m. to keep my job). By framing exposure as individual choice, the environmental justice questions are swept aside and we fail to hold polluters accountable for their impact on our collective health; we simply rearrange our lives to accommodate the smog—those of us who can afford to, that is.

If the politics of these projects are so different, why were they reported as if they are the same? What is wrong with the optics when an environmental justice project by an artist appears the same as a project by a marketing firm to promote a start-up? Why didn’t any news articles reference PigeonBlog? Or, more concretely, why didn’t anyone involved (Duquesnoy? Plume Labs? Journalists?) just google “pigeons” and “pollution sensor” together and learn that Pigeon Air Patrol was not the first time pigeons had been used for pollution monitoring?

Digital Smog

We are living in an age of digital smog.12 An unfathomable amount of information is available at our fingertips, but it seems that, paradoxically, we are becoming less discriminating about how we use it. Information appears to us in an undifferentiated haze, with reliable information interspersed with advertising, propaganda, and conjecture. If you google the famous American science writer and environmentalist Rachel Carson, for example, you are just as likely to be told that Carson is responsible for the murder of millions of people who died of malaria (an opinion propagated largely by corporately funded right-wing think tanks like the Hoover Institution) as you are to learn the importance of her 1964 book Silent Spring in launching the US environmental movement.13 Google’s algorithms do not differentiate between good and bad information, marketing and art.

Digital smog is ahistorical, much like the smog measured by da Costa’s pigeons. Above Los Angeles, nitrogen oxides combine with VOCs and ultraviolet light from the sun in ongoing chemical reactions; molecules cannot be traced to their sources. They lose their histories. Similarly, information on the Internet seems to come from everywhere and nowhere, claims are rarely tethered to their origins, and false quotes and statistics circulate freely. In the reporting on Pigeon Air Patrol, we can see how quickly one version of the story spreads—so quickly that that there was no time to pause and place Pigeon Air Patrol within a history (as coming after PigeonBlog) or in the context of its industry (as, first and foremost, advertising). This kind of decontextualized information is the product of a digital media landscape that Henry A. Giroux argues “erase[s] history by producing . . . a culture of immediacy, speed, simultaneity and endless flows of fragmented knowledge.”14 Here, the speed of the news cycle and the fetishization of innovation conspire against rigorous research and citation, which works just fine for DigitasLBi.

For the rest of us, the results are insalubrious, to say the least. Now more than ever, we’re feeling the effects of digital smog. We’ve witnessed the terrifying rise of clickbait candidate Donald Trump, while Instagram celebrities sell us laxative teas claiming they “detoxify.”15 Although the need for media literacy is higher than ever, I’ve noticed instead an alarming relativism in how my students (most of whom were born in the ’90s) consume media. They tend to see all content online as either equally reliable or, conversely, equally unreliable. It doesn’t matter whether the author is an environmental journalist at a national newspaper or paid by an oil company, because it’s all biased anyway. This can be a dangerous attitude, as we’re seeing in the current election cycle. If we assume that all politicians lie, we don’t hold them accountable for their claims; Trump, it seems, is immune to fact-checking.

Granted, the Internet also allows us to “talk back” to misleading claims that circulate in the media. This past fall, for example, I saw an Airbnb ad on a bus shelter that suggested that San Francisco use the 12 million dollars of hotel taxes generated by Airbnb rentals to keep the libraries open later. It didn’t seem to me like 12 million dollars was very much money for a city like San Francisco. So I did a “back of the envelope” calculation to see how much of that money would actually go to the libraries and posted the results on Facebook. My post went viral giving me a platform that would not have been possible even 10 years ago.16 But these kind of viral phenomena are unpredictable and difficult to leverage when they do happen—journalists contacted me for 24 hours, often with deadlines only an hour or two away; by the time I figured out what I wanted to say, no one was interested in talking to me. Anyhow, I doubt that waiting around for favorable breezes is a long-term solution to digital smog. Although high-profile cases of plagiarism like Melania Trump’s convention speech will likely be caught and called out, the case of Pigeon Air Patrol makes me I wonder how we can actively resist this culture of immediacy and connect things more strongly to their histories.

The Art of Citation

Citation is one way that scholars situate themselves within a history. Footnotes and bibliographies trace the genealogy of ideas and testify that nothing happens in isolation. Although I’m pretty sure that “cite your source” is the professor equivalent of “eat your vegetables,” I wonder if what we need now is more widespread insistence on citation—not just academically rigorous citation, but citation that’s vital, imaginative, and clever. Citation that’s sticky, that attaches, sutures, adheres, remembers, that connects cultural production across space and time, that protects against amnesia and appropriation and does it with style. What if footnotes were scattered across the landscape like Pokémon?

Citation is about performing an obligation to the past, to those who came before us and those who make our work possible. This question of obligation offers one way to make a distinction between artists and advertisers in an age of digital smog. Advertisers have a primary obligation to their clients, whereas artists can pursue, inherit, or stumble into other kinds of obligations. PigeonBlog was a striking artwork because it gave charismatic form to Beatriz da Costa’s commitment to environmental justice, a commitment that insinuated itself when she found herself in LA, breathing in polluted air. How can we give form to our obligations to artists like da Costa when they are no longer with us? How can we continue to invoke their presence, like a mantra, like a séance, like a prayer, before they disappear into the atmosphere?

1) Beatriz da Costa, “Reaching the Limit: When Art Becomes Science,” Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience, ed. Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (Cambridge: MIT Press 2010), 379.

2) The original PigeonBlog website is no longer active. You can see an archived copy here: http://web.archive.org/web/20120111232344/http://www.pigeonblog.mapyourcity.net/. The current internet home of PigeonBlog is here: http://nideffer.net/shaniweb/pigeonblog.php.

3) In 2006, for example, there were news stories on PigeonBlog on the CBS News, New Scientist, CNET, The New York Times, National Geographic, and the LA Times. [http://www.cbsnews.com/news/smog-blog-takes-flight/, https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18925376-000-pigeons-to-set-up-a-smog-blog/, http://www.cnet.com/news/gps-enabled-birds-pollution-fighters-or-animal-cruelty/, http://www.nytimes.com/2006/08/06/arts/design/06fink.html?pagewanted=print&_r=0, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2006/10/061031-gps-pigeon_2.html, http://articles.latimes.com/2006/aug/10/local/me-pigeons10.]

4) Beatriz da Costa, “Reaching the Limit: When Art Becomes Science,” Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience, ed. Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (Cambridge: MIT Press 2010), 379.

5) Kavita Philip, “Art and Environmentalist Practice,” Capitalism, Nature, Socialism 19.2 (2008): 72.

6) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJOXBJ5-1co

7) Adam Vaughan, “Pigeon Patrol Takes Flight to Tackle London’s Air Pollution Crisis,” The Guardian, 14 March, 2016: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2016/mar/14/pigeon-patrol-takes-flight-to-tackle-londons-air-pollution-crisis

8) Beatriz da Costa, “Reaching the Limit: When Art Becomes Science,” Tactical Biopolitics: Art, Activism and Technoscience, ed. Beatriz da Costa and Kavita Philip (Cambridge: MIT Press 2010), 377.

9) http://www.digitaslbi.com/us/about/

10) This number comes from DigitasLBi’s promotional YouTube video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIOwFTr-6hA.

11) The only article from March 2016 to include PigeonBlog was on Hyperallergic: http://hyperallergic.com/287229/pigeons-recruited-to-measure-the-invisible-toxicity-of-londons-air/. The original article didn’t reference PigeonBlog but when someone mentioned it in the comments section they updated the article.

12) The term “data smog” was coined by journalist David Schenk in 1997 and added to the Oxford English Dictionary in 2004. Ironically, despite the fact that our data smog problem has gotten much worse in the intervening years, usage of the term has dropped. I’m using “digital smog” here because I think it’s more in line with our everyday experience—consuming digital media rather than processing data.

13) Naomi Oreskes and Erik M. Conway, Merchants of Doubt (New York: Bloombury Press, 2010), Chapter 7.

14) Henry A. Giroux, “Anti-Politics and the Plague of Disorientation: Welcome to the Age of Trump,” Truthout, 7 June 2016: http://www.truth-out.org/news/item/36340-anti-politics-and-the-plague-of-disorientation-welcome-to-the-age-of-trump

15) Chavie Lieber, “Teatox Party,” Racked, 27 April 2016: http://www.racked.com/2016/4/27/11502276/teatox-instagram

16) For an analysis of the ad and the rhetoric of the tech industry see: https://www.sfaq.us/2016/03/sincerity-camp-and-how-big-tech-got-so-cute/. The article also includes the image of the Airbnb ad that I took on my walk to work.