Cinco Y Cinco/Five and Five

The Mexican Museum

2 Marina Blvd, San Francisco, CA 94123

June 23-November 6, 2016

The Mexican Museum started out as a scrappy storefront in San Francisco’s Mission District in 1975, the vision of founder Peter Rodríguez, an artist who endeavored to exhibit Latino artistic expression. In 1982, the Museum moved to Fort Mason Center, its present location, where its small size and informality belies a treasure trove of over 16,000 art objects of pre-Columbian, colonial, and contemporary Mexican and Latino art works. Rodríguez died at age 90 this year and will not see his Museum become the institution he dreamed of; now partnered with the venerable Smithsonian, the Museum is set to open in 2019 in a 60,000-square-foot space in San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Arts District, where it will join the Contemporary Jewish Museum, Museum of the African Diaspora, and SFMOMA.

Selection of paintings by Bernardo Roman Palau. Courtesy of the Mexican Museum. Photo by Miguel Farias

Any definition of “Latin America” must include the tangled history and blood between Mexicans, Chicano/as, Native Americans and Europeans. Filtering this experience through the individual lenses of 10 artists from several Latin American countries and also the United States, Cinco Y Cinco/Five and Five, features abstract, figurative, and conceptual work by successive generations of Latino artists. (Curator Anthony Torres invited five established artists who in turn invited five younger artists to exhibit with them). The show searches for the loose connections or intersections between these vastly different works in terms of composition or color, subject matter, history, or biography.

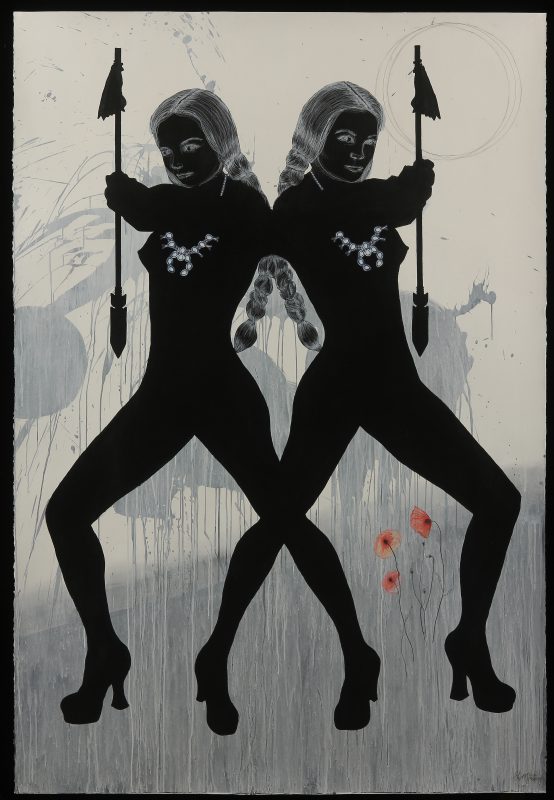

Geri Montano, Moon Dreaming, 2014. Acrylic, ink, graphite, prisma pencil, gesso on paper, 76 x 51 in. Photo courtesy of the artist

Upon entering the gallery across from the front desk you confront a series of life-size silhouettes of twin woman warriors—collaged drawings on paper by artist Geri Montano—who draws from her mixed Native American heritage. Her drawings read like x-rays, taken with a subterranean female power, of images of good/evil, male/female, light/dark, outside/inside, hero/trickster. The first room features more of Montano’s smaller drawings that play on the term “apple” meaning a Native American: apple red on the outside but white on the inside. Also included in the exhibition is Victor Cartagena, who came to San Francisco in the 1980s seeking asylum during El Salvador’s bloody civil war. Using his personal collection of broken and scuffed plastic religious statuettes, saints are lashed to vintage alarm clocks lined along glass shelves, or facing off on a chess board in an imaginary battle. In a series of terrariums, various saints are transmogrified, buried in sand or submerged in water. The spirit of murdered Salvadorian priest Oscar Romero haunts these works. Cartagena questions if life is based on truth and justice or on the insanity of war. Cartagena’s work tussles, both humorously and despairingly, with the contradictions found in the institutions of the Catholic Church and the military that resulted in the killing of thousands of his countrymen.

Bernardo Roman Palau, Crime or Miracle, 2013. Oil paints on canvas, 36 x 36 in. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Bernardo Roman Palau’s paintings feature disquieted, beautifully rendered animals and people that are often obscured by dripped paint and abstract symbols or shapes. Palau mixes traditional European oil painting with Frieda Kahlo-like imagery to create still lifes, landscapes, and fanciful birds, all in meticulous brush work. His Christ Figure (To Carry a Fire Inwards) (2008-2014) shows a large torso laced with tree-like arteries, or lungs, the torso dominating the landscape, a symbol of sacrifice and nourishment.

The second room showcases John Jota Leaños’s video animation Frontera!, a retelling of the making of the southwest borders. This series of videos is inspired by new gaming technology, the Popul Vuh, contemporary Chicano art and comic books and collaborations between him and groups of animators and fellow storytellers from Los Angeles, Albuquerque, and the Bay Area. Sitting at a slot machine in a present-day New Mexican casino, a computer-generated Native American narrator takes you on a tour of the bloody history of the arrival of the Europeans, introducing various historical and magical characters who wander through the permeable physical and cultural borders between The United States and the Americas.

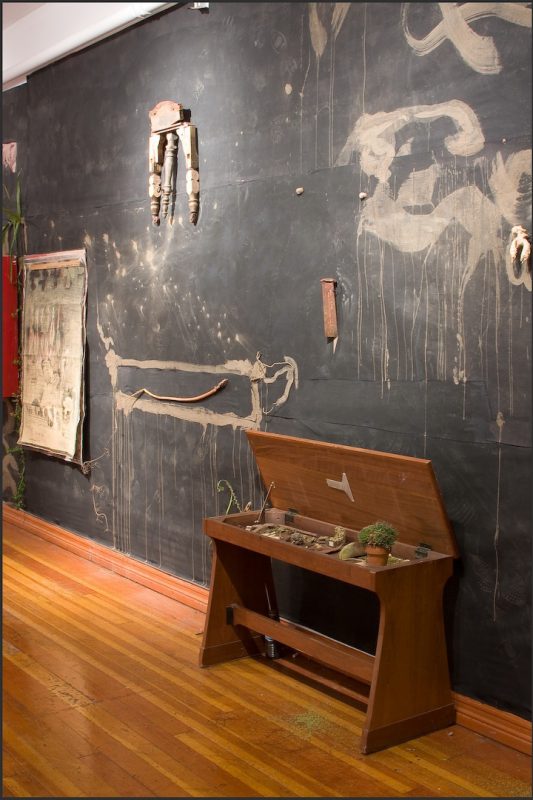

Rolando Castellon, Muro VIII, 2008-16. Mixed media installation. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Also in the second room are Rolando Castellón and Gustavo Ramos Rivera, two founding members (along with René Yañez) of Galería de la Raza, a storefront community art center and gallery (started at the same time as the Mexican Museum) that is still thriving in the lamentably gentrifying Mission District. Castellón, a well-known Bay Area curator, originally from Nicaragua, began using mud in his work in 1981, inspired by fragments of adobe walls, which reminded him of pre-Columbian art. Using traditional methods of weaving grass and sticks with layers of mud, he used the materials to create large wall installations. His large mural Muro VIII (2008-2010) is an amalgamation of painting, drawing, and sculpture occupying the corner of the room. Rivera, originally from Mexico, makes large, bold, colorful paintings. Joyous and abstract, they are crudely painted and in marked contrast to his delicately drawn and beautifully crafted artist books, which mix drawing, collage, and printmaking techniques.

Gustavo Ramos Rivera, Carrousel de sombras/Carousel of Shadows, 2007. Oil paints on canvas, 60 x 60 in. Photo by M. Lee Fatherree, courtesy Elins Eagles-Smith Gallery.

In the same room we find Mexican artist Ana de la Curva’s embroidered map of the United States and an accompanying video, which shows the industrial sewing machine in the process of embroidering. The piece connects maquiladoras, Latin woman’s labor, traditional hand embroidery, and the subject of the Mexican/US border. Adriana Castro drew directly on the Museum wall, with graphite lines creating a schematic map of the building’s history and structure. Gera Loano uses her body as a critical site of personal and political performance. She creates photographic portraits using her face and body that seem both modern and ancient. In an accordion art book, she poses with an unidentified vertebra on her forehead, evoking the idea of ritual sacrifice or a rite of passage.

Finally in the back room, there is American born Lewis Desoto’s personal work, Las Madres Perdidas/The Lost Mothers about his mother’s slow death from dementia. The room is empty except for a ghostly projection, through a clear plastic half mold of a woman’s body, the light-filled image seems conjured by a medium. Quietly introspective, the piece, thanks to the projector’s whirr, has an awkward quality that evokes the transitory nature of human existence. Desoto’s projected mothers and Montano’s monumental women warriors made effective bookends to Cinco Y Cinco.

With more space and a bigger venue in the future, the Mexican Museum continues a conversation with Latin American Artists, a conversation begun in the 1970s and that, happily, shows no signs of ending anytime soon.