Agnes Martin

Los Angeles County Museum of Art

5905 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90036

April 24, 2016 – September 11, 2016

Into my mind there came a grid, and it looked like innocence. –Agnes Martin

Agnes Martin’s current retrospective at Los Angeles County Museum of Art—organized by Tate Modern, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, and the Guggenheim—spans nearly five decades of her work up until her death in 2004 (she was still painting at age 92) and contains more than 100 paintings, drawings, and sculptures. The exhibition, which began in London and then moved on to Düsseldorf and is now in Los Angeles, will later travel to the Guggenheim in New York in the fall.

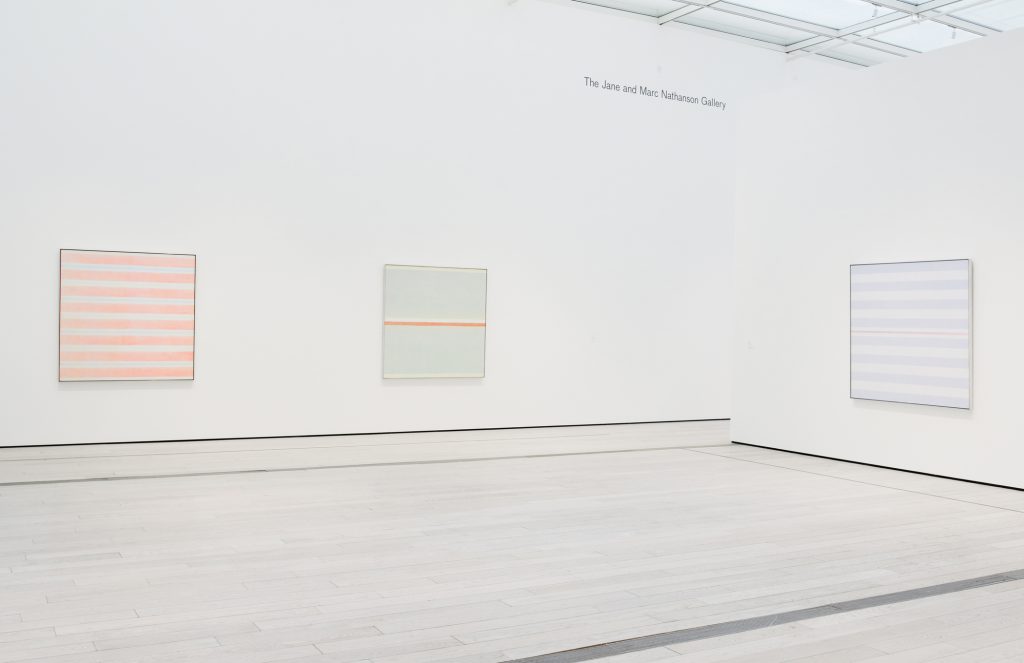

Installation view, Agnes Martin, April 24 – September 11, 2016. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Art © Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

When you enter the exhibit at LACMA you discover that, except in the rooms where there are works on paper, there is no artificial lighting. Rather, the space is lit by diffused natural light, which intensifies the intimacy of looking at Martin’s painting: the subtle variations of the pencil lines, the thin washes and layers of paint that seem to sit on the surfaces of stretched canvas. Frances Morris, one of the Tate Modern curators, describes the “remarkable visual effects of translucency and tremolo.”[1] The modern syntax of Martin’s grids, formal in appearance, are far from cold, and vibrate with emotion, with a powerful human feel. The irregularity and sensitivity of hand-drawn lines seem like meditative recordings of her emotions. Martin rejected the label of “minimalist” and said she had more in common with the abstract expressionists of her generation, saying her work was always about feeling, about innocence.

Agnes Martin, Untitled, c. 1955, oil on canvas, 46 1/2 × 66 1/4 inches, private collection, © 2016 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo courtesy Pace Gallery

In the 1950s, gallerist Betty Parsons invited Martin to be in her stable of artists on the condition Martin leave her home in New Mexico and move to New York City, and this began Martin’s 10-year residency at Coenties Slip—an artist enclave in Manhattan’s South Ferry district—which included the artists Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns, Ellsworth Kelly, and Ad Reinhardt. LACMA features her early assemblages of detritus from the lower Manhattan docks, and dreamy, lyrical biomorphic works in the spirit of Joan Miró or Arthur Dove. Also included in her early work are shimmering little paintings of lines and dotted mark like calligraphic details from pages of illuminated manuscripts, perhaps foreshadowing her direction of large grid works.

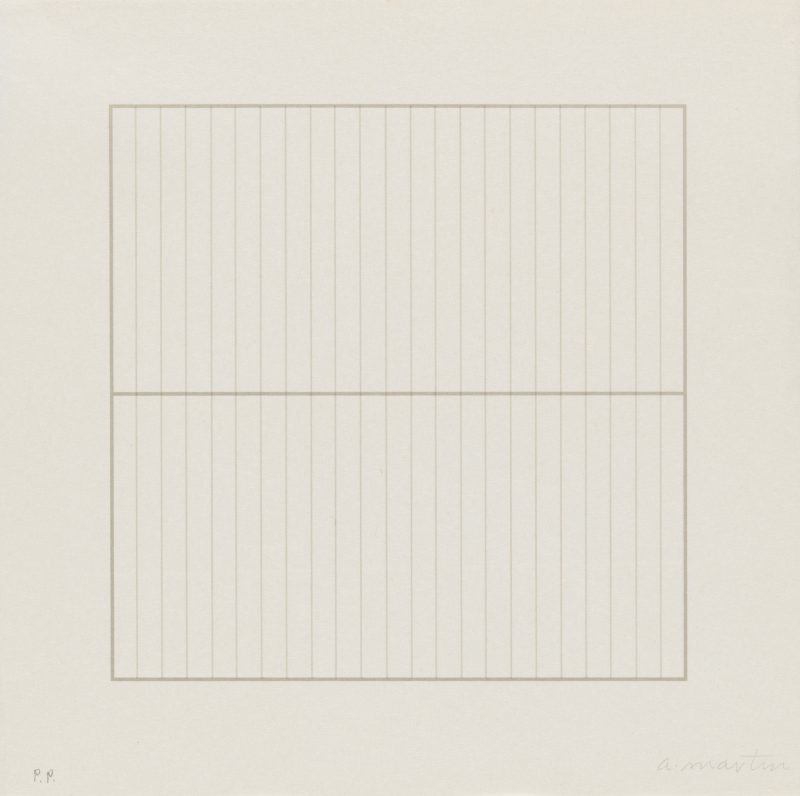

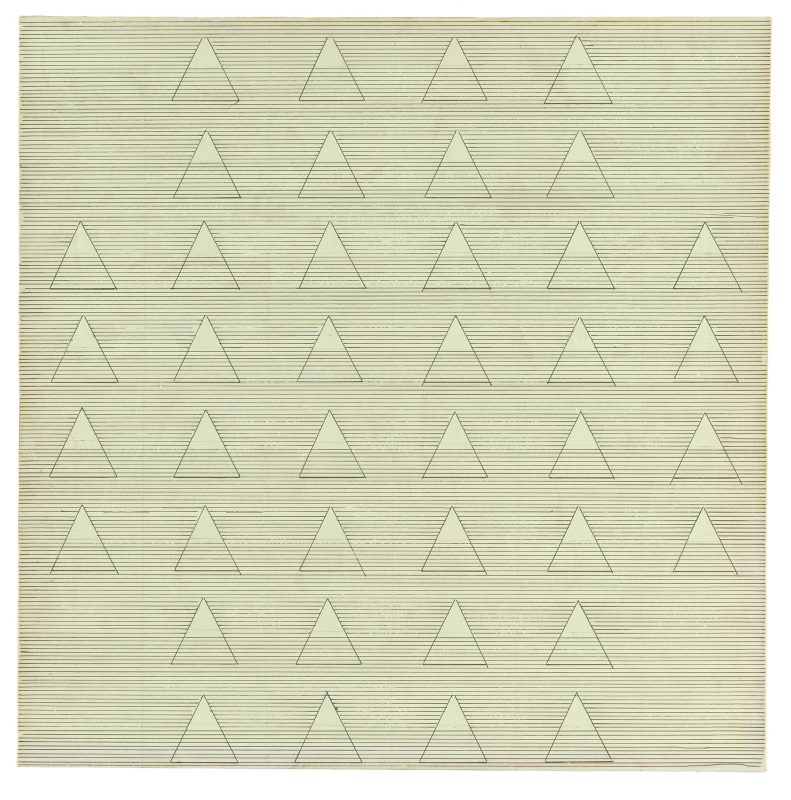

Agnes Martin, Untitled from the portfolio On a Clear Day, 1973, one of thirty screenprints, 12 × 12 in. (30.4 × 30.4 cm). Los Angeles County Museum of Art, purchased with funds provided by the Kotick Family Foundation in honor of Lynda and Stewart Resnick through the 2007 Collectors Committee, © 2016 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photos © Museum Associates/LACMA

The LACMA exhibition is organized in two parts: early works and later works. On a Clear Day, a suite of 30 screen prints, serves as a bridge between the two halves. Each print in Day is one-foot-square, on Japanese paper, and is composed of thin, ruled, grey or black line drawings that form gridded patterns of different sizes, limited colors, and intervals. Her mostly grey palette forces your attention to the grid.

The second half of the space features her later style, including A Rose and White Stone from the 1960s. The Islands I-XII (1979), a group of seven white paintings, each marked with nearly invisible pencil lines (and that Martin considered a single piece), sadly was not included in the LA County exhibition, but was included in the original show at the Tate. A number of the later pieces are untitled, and they feature both horizontal and vertical lines with larger intervals between them in soft pastel colors, immersive emotional landscapes with the pink, yellow, and blue hues of the dawn sky in New Mexico.

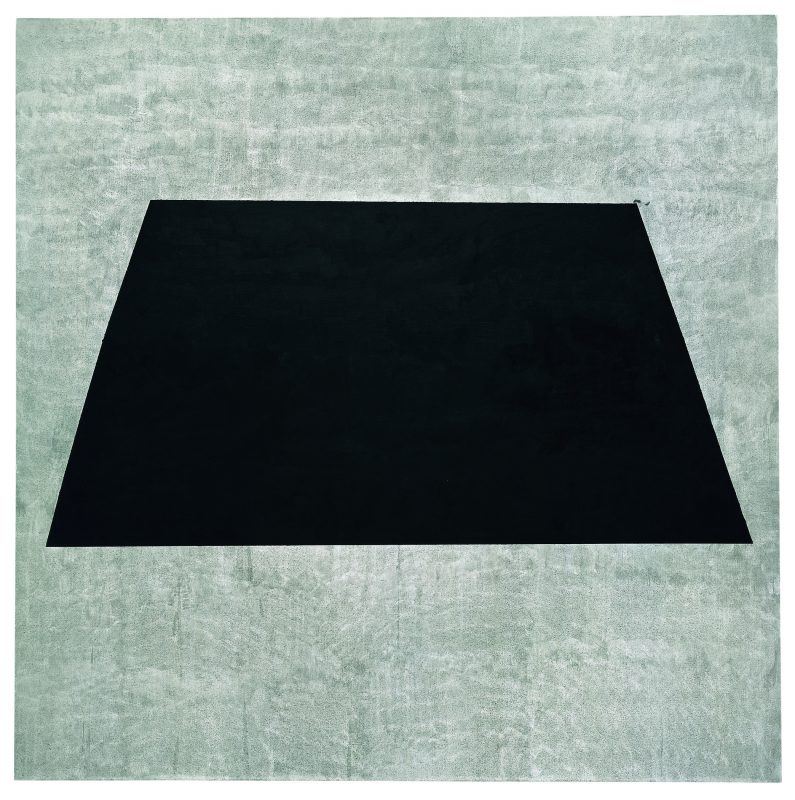

Agnes Martin, Homage to Life, 2003, acrylic and graphite on canvas, 60 × 60 inches, Leonard and Louise Riggio, © 2016 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo courtesy Pace Gallery

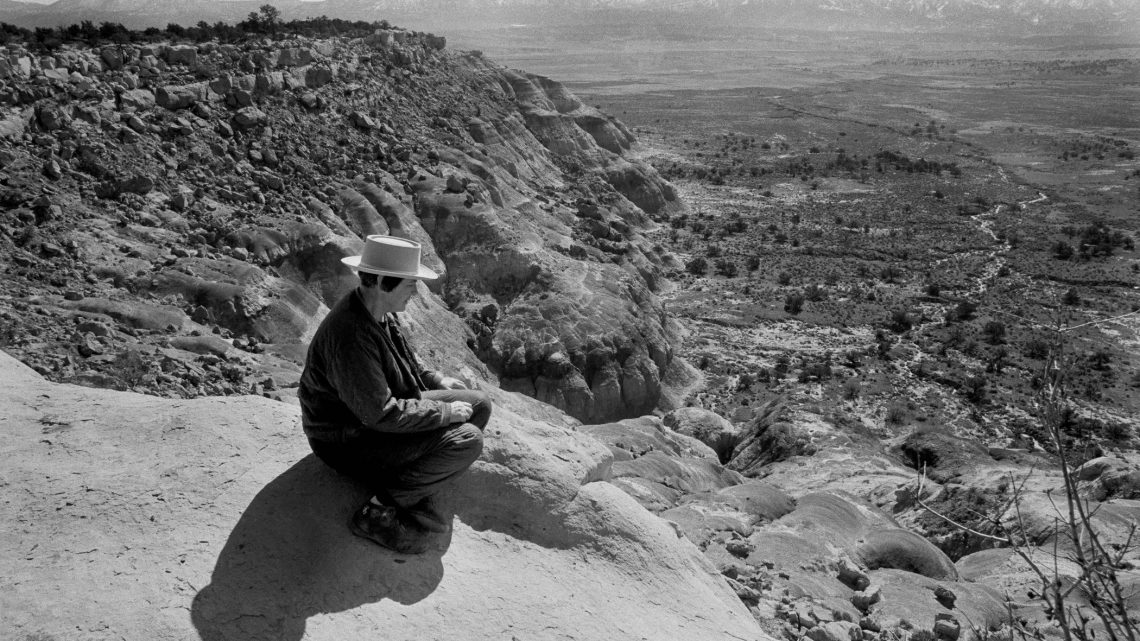

In Herman Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” (1853), an erstwhile dutiful clerk decides to give up his job, saying simply, “I would prefer not to.” Whether it was losing her studio slated for demolition, the break up with her lover, the NEA grant that she used to buy a truck, or the sudden death of her friend, Ad Reinhardt, Martin, who was by now a successful artist, left New York and wandered on an extended road trip which brought her to New Mexico: Cuba, Galisteo, and finally settling in Taos. It was in New Mexico that she began painting again after a 5-year silence. Nancy Princenthal’s recent biography, Agnes Martin: Her Life and Art (2015), chronicles Martin’s successive hospitalizations for paranoid schizophrenia; also a lesbian who lived in pre-Stonewall New York City, she was an artist in a male artist’s world. Both Princenthal and Martin resist interpreting her work from her personal history.[2] In an interview with John Gruen in 1976 Martin remarked:

“Toward freedom is the direction that the artist takes. Art work comes straight through a free mind — an open mind. Absolute freedom is possible. We gradually give up things that disturb us and cover our mind. And with each relinquishment, we feel better.”[3]

Agnes Martin, Words, 1961, ink and paper mounted on canvas, 24 x 24 inches, Thomas Ammann Fine Art AG, Zurich, © 2016 Agnes Martin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, photo courtesy Thomas Ammann Fine Art

Martin, a lifelong student of both western and eastern philosophies, encountered Zen and regarded art as a meditation, or ritual, a way to lose one’s ego. Martin’s serene paintings, from youth into old age, always seem fully formed, as if born from the forehead of Zeus, born from her earthly/otherworldly sensibility. The viewer’s response is the real art, Martin once said, and she wanted to provoke “that quality of response from people when they leave themselves behind, often experienced in nature, an experience of simple joy.”[4]

—

[1] http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2015/06/agnes-martin-tate-modern

[2] http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/talks-and-lectures/agnes-martin-innocence-hard-way

[3] John Gruen’s The Artist Observed: 28 Interviews with Contemporary Artists (1976), 4.

[4] Ibid.