The Keeper

New Museum

235 Bowery, New York NY 10002

July 20 – September 25, 2016

“To say a thousand nights is to say infinite nights, countless nights, endless nights. To say a thousand and one nights is to add one to infinity.” -Jorge Luis Borges, The Thousand and One Nights, translated by Eliot Weinberger (New York: New Directions books, 2009), 45.

Blackly monochromatic eyes gaze inscrutably out of three thousand family-album photographs that haphazardly coat the walls in a seeping, crooked grid. The flushed skins of one hundred twinned apples and pears are caught in pencil and watercolor against velvety black. A supple, boyish figure bends under the weight of the years in the 63 annual portraits that etch out a life in deepening wrinkles and thinning hair. Four floors of the New Museum are interlaced with a web of assemblages and correspondences, making up the exhibition The Keeper.

Collections vary in their intentionality; many of us have hundreds of plastic bags stuffed beneath the sink; thousands of casual snapshots dormant in overfull hard-drives. We look happily upon such cached keepsakes even as we consign them to oblivion, sure that someday we will be grateful that we were prepared, that we haven’t forgotten. Museums and archives bear more purposeful gatherings, charting the suppositions that we call science and the mythologies that we dub history in reliquary records and documentary artifacts. Such are the gestures of archives: holding on, making infinite, and striving beyond material mass to reach for answers to the perennial questions of how to remember and how to know. Bringing together the idiosyncratic accretions of 30 artists and individuals, the exhibition mines the meaning of ‘collection’ in all of its facets, examining memory both personal and cultural, reasoning the motives for accumulation and systemization.

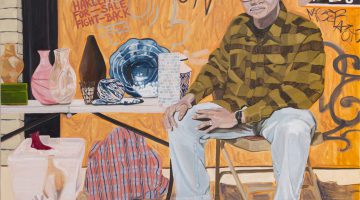

Howard Fried, The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe, 2014-ongoing. Courtesy of the Artist and The Box Gallery. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen Studio.

Life itself is chronicled in emphatic expressions of labor and vitality. Weltrettungsprojekt (1995-ongoing) is Vanda Vieira-Schmidt’s indefatigable effort to save, potentially the world, but more likely her own sanity through prescient drawings produced daily by the hundreds. In limp but colorful opposition, Howard Fried’s The Decomposition of My Mother’s Wardrobe (2014-ongoing) remembers a loved one in the smell of detergent, the threadbare softness of a habitual sweater, and the cool touch of skin against silk. However, these treasured mementos are also met by a willful act of dispersal as Fried catalogues each item only to bestow it on another, inviting others to partake of these remnants on the conditions that they allow themselves to be photographed with their new property and wear it to a future celebration. The memories made manifest in handbags and floral patterns will find new skins to rest against, new lives to color.

Yuji Agematsu (b. 1956, Kanagawa, Japan), 01-01-2014 – 12-31-2014 (01-01-14 – 02-29-14), 2014. Mixed mediums. Dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Real Fine Arts.

At their most direct, the works in this show wonder at the way in which we attempt and fail to impose order upon an infinitely possible world, an effort as impossible as that of capturing the clouds—though we have, in fact, begun to number the stars. Dirt and detritus are collected and recorded with a scientific exactness by Yuji Agematsu, as field samples from his explorations of the streets of New York. In cases illuminated from below, the dark spectrum of Roger Caillois’s stone collection is arrayed, presenting one hundred “irreversible cut[s] made into the fabric of the universe.”[1] Wilson Bentley’s photo-documentation of snowflakes captures the never-ending variety of the crystalline forms which are “too quirkily particular to cooperate in generalizations and comparisons.”[2] Such a compromised neutrality can imagine an evolution equally capable of producing both the Bactrian Camel and the Ring Tailed Sockdologer, animals real and imagined, captured in wooden relief by Levi Fisher Ames. How could a truly systematic catalogue hope to comprehend the origin stories documented by Susan Hiller, who chronicles languages and laughters that are becoming variably “endangered” or “extinct”?

Selection of 188 stones from the collection of Roger Caillois, n.d. Dimensions variable Collection Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris

These intersections of obsession and objectivity challenge the distinctness of dispassionate history and imaginative storytelling, revealing a spectrum that houses religion, art, and alternative narratives in a lineage surpassing the present. History is written only to reveal itself in these objects as “recalcitrantly material, fragmentary rather than fungible…. so many promissory notes for further elaboration…”[3] What is the difference, after all, between the work of Maurice Chehab’s preservation of ancient Lebanese artifacts and the salvation of Peter Fritz’s model houses by Oliver Croy and Oliver Elser? Henrik Olesen and Carol Bove demonstrate the ability of collection and presentation to be more than a conservative impulse, but rather a means of making new again. Olesen’s didactic collages do not precisely write an alternative history so much as they reinterpret that which is already there, wishing female empowerment and homosexual desire into the bodies of paintings from long ago. Bove’s imposing forms assert presentation as a mode of interpretation, offering us Carlo Scarpa’s sculpture as mediated by her own. In the curation of Bove’s and Olesen’s works, we may understand a museum’s thoughtful disclosure of its own work, making explicit the preservation, re-collection, and interpretation that are always latent in the function of our institutions.

Installation shot of Carol Bove and Carlo Scarpa. “The Keeper,” 2016. New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

We are allowed a glance into archives so infinite that they speak to the impossibility of freezing time. The wind of butterfly wings stills and levels with Vladimir Nabokov’s blushing page. Clothes that straighten after use iron themselves into the patterns of the Pettway family’s patchwork quilts. Not about the past so much as about the attempt to return to the present, these works endeavor to hold onto something, to disappear less. In collections as idiosyncratic and inexplicable as their makers, The Keeper speaks of the searching and researching that is both about knowing and about being unable to know.

—

[1] Roger Caillois, Pierres, translated by Marina Warner (Paris: Gallimard, 1966), p. 117.

[2] Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2007), 22.

[3] Hal Foster, “An Archival Impulse,” in October 110, no. 3 (2004): 5.