Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett

American Folk Art Museum

2 Lincoln Square, New York, NY 10023

June 21 – September 18 2016

Humble and harrowing, Fever Within: The Art of Ronald Lockett—a retrospective of self-taught southern artist Ronald Lockett now on view at the American Folk Art Museum in the Upper West Side—serves as a much delayed but deserved recognition of the little-known, often overlooked, African American painter.

For those familiar with Lockett, the artist might be remembered for his sorrowful large-scale assemblages, like Traps (1992) or Rebirth (1987), which pair vernacular imaging with an interest in materiality. Lockett often made work from materials such as tree branches, corrugated metal, chainlink fences, vacuum hoses, and house paint—tapping into the substances’ sociopolitical and narrative valences.

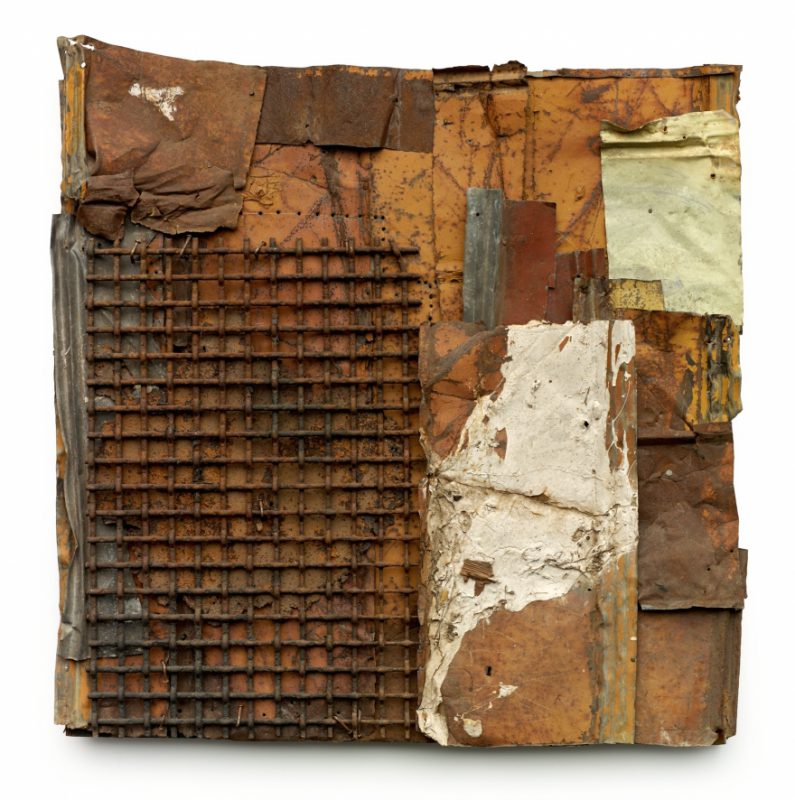

Ronald Lockett, Timothy, 1995. Found sheet metal, tin, wire, paint, nails, on wood, 45 x 43.25 x 3 inches.

Lockett spent his entire life at his mother’s home in Pipe Shop, a steelworkers’ neighborhood in Bessemer, Alabama—the industrial hub embodying the Black Belt’s transition from cotton fields to factories and mills. He was heavily encouraged by his cousin—whom he often referred to as his uncle—artist and Bessemer resident Thornton Dial, Lockett’s particular style grew out of his deep enmeshment in and commitment to this community. This is not to say that Lockett was particularly at home in his home. The artist was noted for lacking the masculine toughness typical of Pipe Shop factory workers.

Ronald Lockett, England’s Rose, 1997. Tin and paint on wood, 48.25 x 48.25 inches

The conversations Lockett had with Dial, the environmental degradation apparent in the region (the materials that literally littered the landscape), the community’s feeling of spiritual and economic impoverishment (stemming from an ethos of post-civil rights disillusionment and protracted racial and economic inequity), as well as the artist’s own disconsolate romantic life and personal battle with HIV and AIDS, all proved deeply influential on his work.

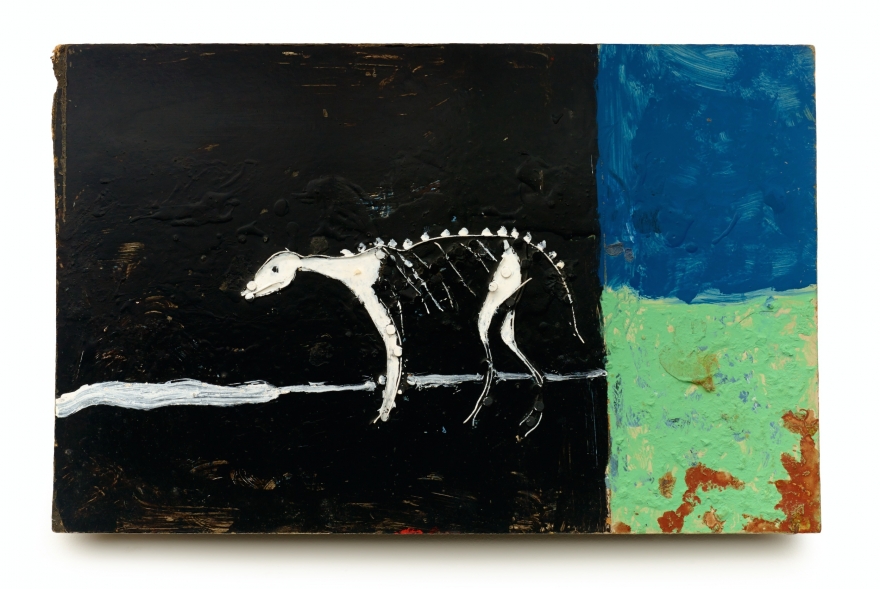

Locket passed away in 1998, at the age of 33, from HIV/AIDS-related pneumonia. And, Fever Within successfully showcases the gravity of his markedly short-lived career. For example, in Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die (1996)—a painting depicting a fragment of a sandy-colored deer fading into a sea of rusted tin—Lockett’s intimate understanding of the boldness of suffering is merged with a poetics of playfulness and vulnerability.

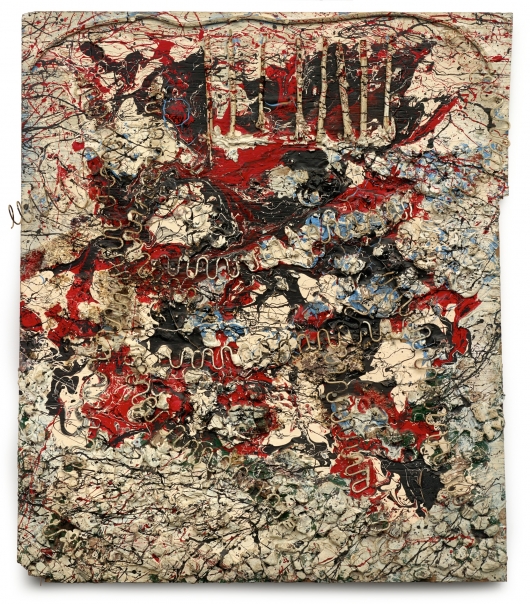

Ronald Lockett, Civil Rights Marchers,1988. Wood, metal, rubber industrial sealing compound, paint, on wood, 48 x 48.5 x 4.5 inches

That being said, Lockett’s work evades easy categorization, often skirting the line between art brut and the canonical. In the main gallery’s foyer hangs Civil Rights Marchers (1988)—a splatter paint assemblage, pairing wood and coils of metal with rubber sealing and house paint; this particular piece not only depicts Lockett’s own imagining of a collective memory (the verve and pandemonium surrounding civil rights demonstrations) but also strikes up formal conversations with the works of Jackson Pollock and Julian Schnabel. In addition, on a platform atop the museum’s diminutive set of stairs sits Untitled Elephant (1988)—a Picassoesque goat-like sculpture fashioned from a sawhorse and vacuum hose. And, on the rear wall hangs a collection of Lockett’s rusted-metal paintings (such as Timothy [1995], Drought [1994], and the Oklahoma [1995]), which seem to find overlap with both Color Field painting and the interests of John Chamberlain and Richard Serra.

Ronald Lockett, Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die, 1996. Wood, enamel, graphite, tin. found materials, industrial sealing compound, on wood, 57 x 50.5 x 4 inches

However, the exhibition fails to stop at a mere overview of Lockett’s stylistic breadth. The depth of emotion present in the artist’s work is highlighted by a complimentary show, Once Something Has Lived It Can Never Really Die, which the museum is holding in an adjacent gallery. This show marries some of Lockett’s more sizable assemblages with eighty-or-so diminutive, mostly portable works concerning mortality and eschatology from outsider artists around the world, such as the knitted womb-like sculptures of Sandra Sheehy and a collection of Brazilian ex-votos. This supplemental exhibition then complicates Lockett’s oeuvre, illustrating how the artist’s work not only relates to a particular historical and geographic circumstance but also by extending beyond this context, entering into a more universal conversation about suffering and death.

Ronald Lockett, Untitled Elephant, 1988. Wood sawhorse, wire, vacuum-cleaner hose, industrial sealing compound, paint, 30 x 54 x 9 inches.

—

Fever Within was produced in collaboration with Souls Grown Deep Foundation, an Atlanta, Georgia-based non-profit committed to archiving, publication, and exhibition of self-taught southern African American artists.

*All images courtesy of Souls Grown Deep Foundation