Ivan Iannoli

Bass & Reiner

1275 Minnesota Street, San Francisco, CA 94107

June 10–July 2, 2016

The eight modest assemblages that make up the majority of Ivan Iannoli’s exhibition at Bass & Reiner slip easily between photography, printmaking, collage, and drawing, eluding fixity in any one media as the artist interrogates the physicality of the art object. Mixing borrowed images with his own, and layering and obstructing them in the frame variously with painted plexi, shards of drywall, and torn construction paper, Iannoli uses a process-driven approach to investigate the relationship between a photograph, the subject it indexes, and the viewer.

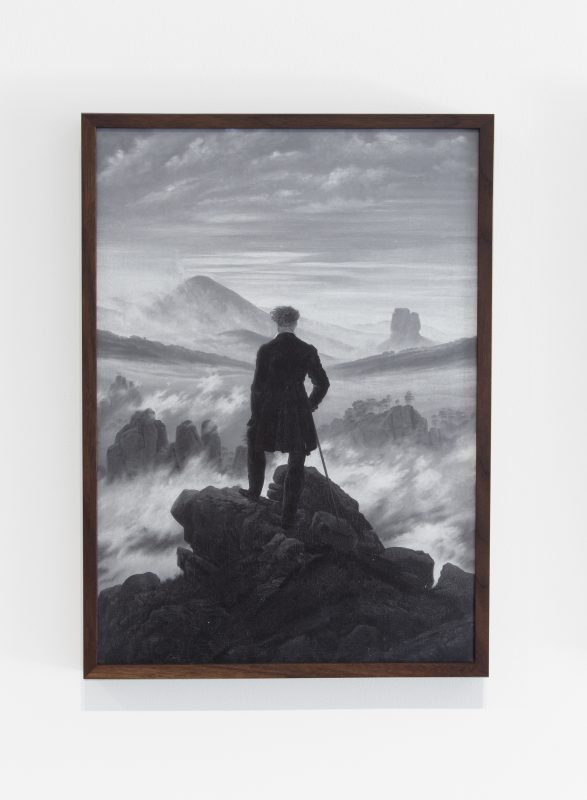

Ivan Iannoli. Untitled (Friedrich), 2016. Digital c-print, edition of 5, 14 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Bass & Reiner Gallery, San Francisco.

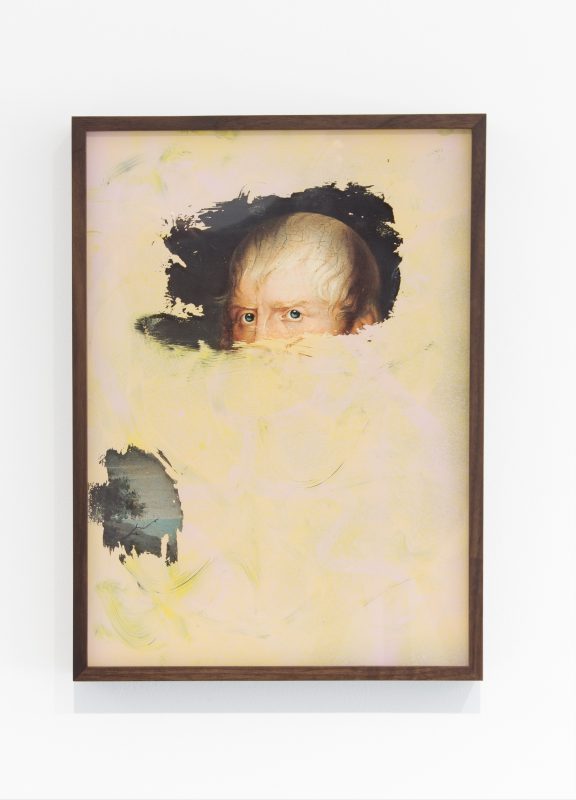

Two works most explicitly draw on the work of German romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich: Untitled (Friedrich) and Untitled (Portrait) (all works cited 2016). The former is an image of Friedrich’s iconic painting, Wanderer above the Mists (1817-8), printed in black and white instead of in the moody blue and grays used in the original. On the wall nearby, the latter is a reproduction of a portrait of Friedrich painted after his death by Albert Freyberg from an actual portrait (painted during Friedrich’s lifetime) by Caroline Badua. The original portrait features Friedrich posed against a background that, with its trees and ocean receding at the horizon, nods to Wanderer above the Mists. Iannoli’s version adds further remove from the original by painting golden toned acrylic and spray enamel on the plexi part of the frame, obscuring all but the top part of the artist’s head and eyes, and a small corner that shows a snippet of outstretched branches and azure. In both of these artworks, the artist plays with materials to remind viewers that images are always at a remove from direct experience.

Ivan Iannoli. Untitled (Portrait), 2016. Spray enamel and acrylic on plexi, digital c-print, 14 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Bass & Reiner Gallery, San Francisco.

On view is also Iannoli’s first projected light work. A witty expansion from the artist’s framed work, Untitled (Landscape) employs the same 14 x 10 inch scale of the other pieces, but is instead presented on a metal stand near the back of the gallery. Sandwiched between glass painted blue, pink, and yellow, a photo transparency depicts a river cascading through a narrow channel. On a pedestal nearby, a projector transmits a single-channel video through the glass panel, effectively animating the still scene in the transparency by adding movement to the water in the channel and a set of hands artfully gesticulating. With images cast on the walls both in front of and behind the object, Iannoli explodes the flat picture plane into multiple dimensions, a sort of photographic geologic elevation. Refracted in this way into several viewing levels, Landscape is another instance of the artist revealing the semiotic underpinnings of photographic images.

Ivan Iannoli. Untitled (Gradient), 2016. Airbrush on plexi, spray enamel, acrylic paint on plexi, 14 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Bass & Reiner Gallery, San Francisco.

Charlotte Cotton, in Photography Is Magic, characterizes practices like Iannoli’s, and the new ways they engage with photographic processes. She argues that these destabilizing practices “are intended to be experienced in this moment of a decidedly flattened image hierarchy.” Iannoli’s work in this spare, well-edited exhibition underscores this flattened hierarchy, using images of images, obfuscated by paint or plexi, to create a very literal distance between the viewer and the object. The result is a visual experience that remains just beyond the grasp of the viewer.

Ivan Iannoli. Untitled (Drywall), 2016. Acrylic, spray enamel on plexi, acrylic on drywall, digital c-print, 14 x 10 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Bass & Reiner Gallery, San Francisco.