Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun

The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012

February 21 – September 12, 2016

At one point in Wim Wenders’ film The American Friend (1979) the protagonist, a frame-maker at the highest level of a dying craft, slowly leafs through a pad. He removes from it a small golden rectangle. Held up suspended on the edge of a knife, it quivers in an otherwise imperceptible draft. He then applies this rectangle of gold leaf to the edge of his thumb. A gilded thumb: the organic and the inorganic fuse into an emblem of one of the most durable fantasies about the visual arts, that it is a realm wherein the most ephemeral and fugitive aspects of experience are rendered stable and open to relaxed exploration. Additionally, what is preserved is a thing of this world that is also a piece of the artist’s self, her ways of seeing, her labor, and her care.

Hito Steyerl, one of the most widely celebrated of contemporary artists, has set herself against this fantasized aim and its associated pleasures, those of recovery, reparation, and preservation, as something inappropriate to contemporary art and life. Rather than taking on this search for lost time and fugitive expression, she thinks that one ought to hold fast to the diagnosis that to be in the twenty-first century is to be the target of cameras. But, Steyerl writes, that cameras now “drain away your life. . .In fact it is a misunderstanding that cameras are tools of representations; they are at present tools of disappearance.”[1] She cites Wenders in particular as oblivious to our new condition: “I remember my former teacher Wim Wenders elaborating on the photography of things that will disappear. It is more likely, though, that things will disappear if (or even because) they are photographed.”[2] Is there a way through a photographic art to escape our contemporary condition as subject to surveillance photography? A second feature of our contemporaneity, she thinks, is our sense that we live in a world of unsurveyably vast number of ways of living. What sort of art, and what conception of artistic form, permits acknowledgement of this array. How can one bring some order to this variety in art without reducing some distinct forms of life to a dominant conception?[3]

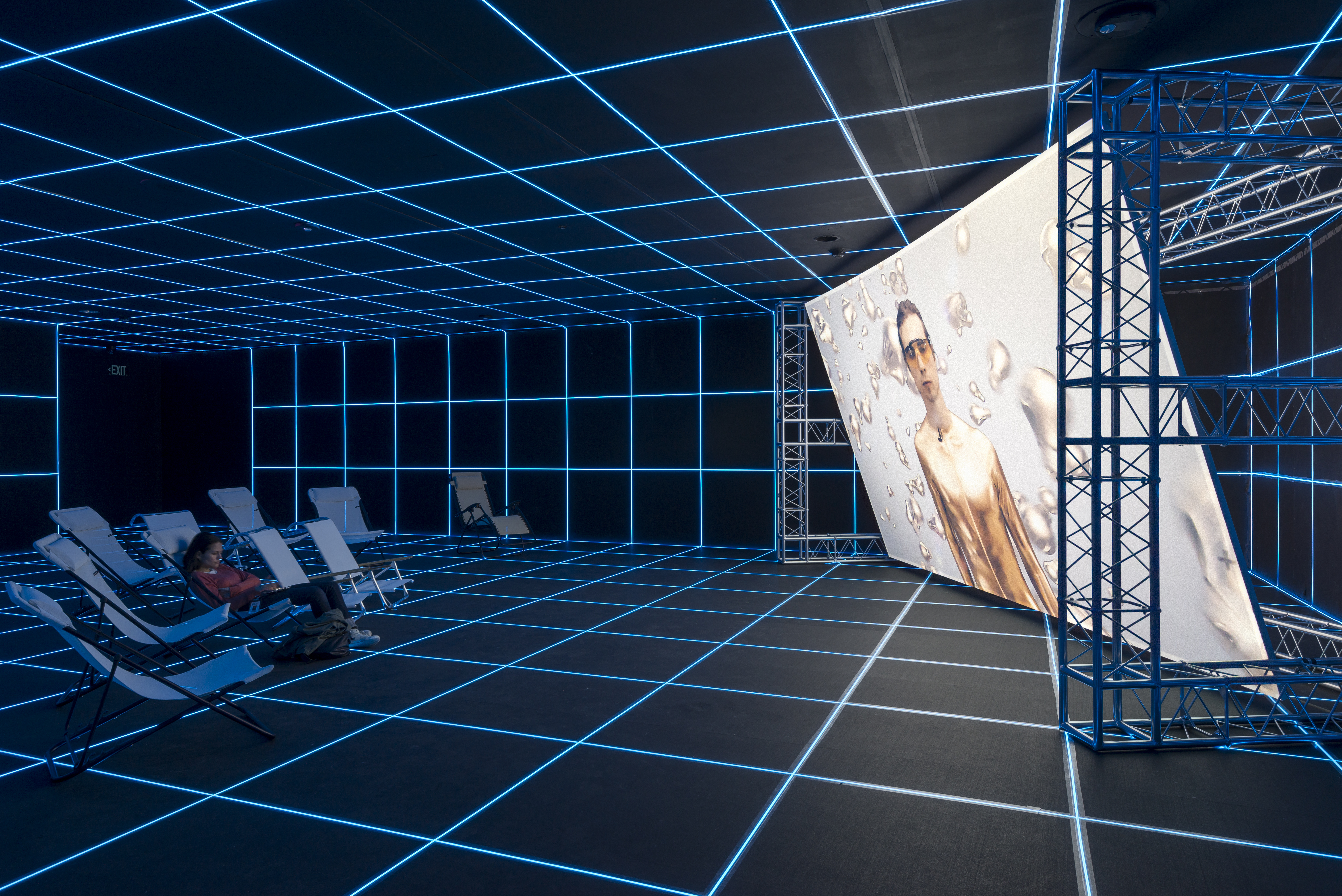

Installation view of Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun, February 21–September 12, 2016 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Justin Lubliner

Steyerl’s film-installation Factory of the Sun, designed for and first shown at the German Pavilion of last year’s Venice Biennale, is now being shown at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Cocooned in its own room amidst what has long seemed to me to be the most dismaying collection of art this side of a freshly stocked Aztec skull rack, the piece offers by contrast an instance of contemporary art at, if nothing else, its most determinedly ambitious. The focus of the piece is a twenty-minute film. Some low-slung beach chairs are casually arrayed in front of a large screen, tilted down towards a seated viewer, and upon which the film plays continuously. The darkened room is covered in a visually stunning blue perspectival grid, which one comes to learn mimics that of a motion-capture film studio shown in the film. In terms of the recent barbaric coinage of ‘instagramability,’ the installation has a high degree of it, though the film itself has a kind of visual density and rapid cutting that demands an attention so focused as to cause the room to slip out of the viewer’s awareness.

@nastygal, Great art doesn’t always mean great selfies. #HitoSteyerl. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

Steyerl has at least half-seriously described the film as ‘a mess,’ but the messiness might well be thought of as intrinsic to an artistic conception that aims to register the unsurveyability of contemporary life.[4] She draws from three disparate sources of material: the first is the story of Yulia (her real-life assistant), whose harrowing family background as a Russian Jewish émigré is invoked. Yulia’s main role though is as the inventor and producer of a computer game. The second source, and the one that comes to dominate, is material associated with Yulia’s real-life brother, who has gained a peculiar sort of contemporary fame for posting videos on YouTube of himself dancing to the pop songs of Donna Summers and others. Steyerl has said that these videos are particularly popular in East Asia, and their dances are modeled after various anime characters. The third source is more heterogeneous, including a range of contemporary dystopian motifs evoking universal surveillance, drone strikes, and corporate cover-ups and disinformation. One thematic thread running through this diverse material is given in the piece’s title, Factory of the Sun: Steyerl aims to present all matter as if existing only as an image (which of course it also quite literally is in the film), and to present images themselves as only ever transforming packets of energy. The process begins with the sun’s emission of energy (‘factory of the sun’ with the word ‘of’ as a subjective genitive), which congeals temporarily into visible images that in turn transform themselves into images of light, in particular light bulbs or gleaming, floating shards (‘of’ as an objective genitive: all objects are surrogate suns).

Installation view of Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun, February 21–September 12, 2016 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Justin Lubliner

Steyerl has written of what she calls the ‘poor image’ as a mechanism through which our visibility is alienated from ourselves and is transmitted uncontrollably through pirating, surveillance, and the Internet.[5] The dancer becomes the figure of the poor image through the dances’ global dissemination. Early on he is shown in the motion-capture studio as Yulia directs him to act as if he sights a drone that quickly kills him. Much of the film’s soundtrack is a techno beat to which he, at times, dances alone in various locations, while at other times with four of Steyerl’s assistants, and yet at others where anime figures dance separately or in unison. The dances themselves are among humanity’s coldest creations: the dancers face the viewer; in ensemble they are evenly spaced, with a kind of hierarchy of depth, the foremost being most salient. The dances are structured in short repetitive sequences, with no transitional phrasing or emotional arc. Phrases are generated by rapid movements of the major joints (shoulders, elbows, wrists, hips, knees, and ankles) in punctuated oscillations among two or three positions. The face is kept in an expression of blank earnestness, save for a bit of expressed pleasure from the two female assistants as they try to mimic and learn the dancer’s movements. The dancer is allowed a single bit of conventional expression, a kiss to the camera at the end of one of his original videos.

The film ends with a break in its visual style; an imageless screen of text announces that the film has been hacked. Pulling herself out of the low chair, the viewer is left to reflect upon the continuity between the depicted motion capture studio and the actual gridded space she re-finds herself in. The most common action I witnessed after four viewings of the piece was the viewer standing up, checking out the screen and its scaffolding, taking a couple of selfies, and leaving. A bitter thought suggests itself: the open proliferation of the poor image has been introjected into the piece as the viewer, and the viewer finds herself as another image, soon to be posted on the Internet and thereby alienated from the person whose image it is.

Installation view of Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun, February 21–September 12, 2016 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Justin Lubliner

Steyerl’s writings and previous work reveal chief points of artistic orientation and reflection in the Soviet arts of the 1920s, especially those of the filmmaker Dziga Vertov and the writer Sergei Tretyakov. She quotes Dziga Vertov on the idea that a film can set up or instantiate a ‘visual bond’ among its viewers, while chiding him for naively thinking that such a bond could be an aid for workers in overcoming their collective alienation and grasping and articulating their collective control over the means of production.[6] So instead Steyerl treats the poor image of the dances in the manner of a wised-up and disenchanted realism: here is the uncontrollable proliferation of whatever is seen and photographed. This trajectory takes the role of a mechanism of unifying the heterogeneous material presented in becoming a kind of attractor, drawing each figure to it, while being subjected to nothing else. The coldness of the dance is the other side of its trans-personal power of giving whatever unity there can be to an ambitious work of contemporary art that is alive to our contemporary situation.

But what if such realism is just a kind of failure of imagination?

Installation view of Hito Steyerl: Factory of the Sun, February 21–September 12, 2016 at MOCA Grand Avenue, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Justin Lubliner

—

[1] Hito Steyerl, The Wretched of the Screen (Sternberg Press, 2013), p. 168

[2] Ibid, p. 175, n.10

[3] In a recent public discussion, ‘What is Contemporary?’, Steyerl says that “it is really important to try to suspend [in one’s art work], because you cannot get rid of the disjointedness of contemporary situations” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sNW1PP-034Q, at 54:12-54:23)

[4] In ‘What is the Contemporary’ at 16:27 and 54:05

[5] The Wretched of the Screen, pp. 32-45

[6] Ibid, p.43, citing Dziga Vertov, Kino-Eye (University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984), p.52. There Dziga Vertov writes: “How, therefore, can the workers see one another? Kino-eye [i.e. cinema practiced under Dziga Vertov’s conception of presenting workers with truths relevant to their situation qua workers] pursues this goal of establishing a visual bond between the workers of the entire world.”