Who We Be

The Cantor Arts Center

328 Lomita Drive, Stanford CA 94305

Through June 27, 2016

Racial tension—unified by marketing campaigns, exploited by television news, tentatively explored by mainstream press, and viscerally unearthed by works of art—is what structures the exhibition Who We Be, running through June 27, 2016 at the Cantor Arts Center.

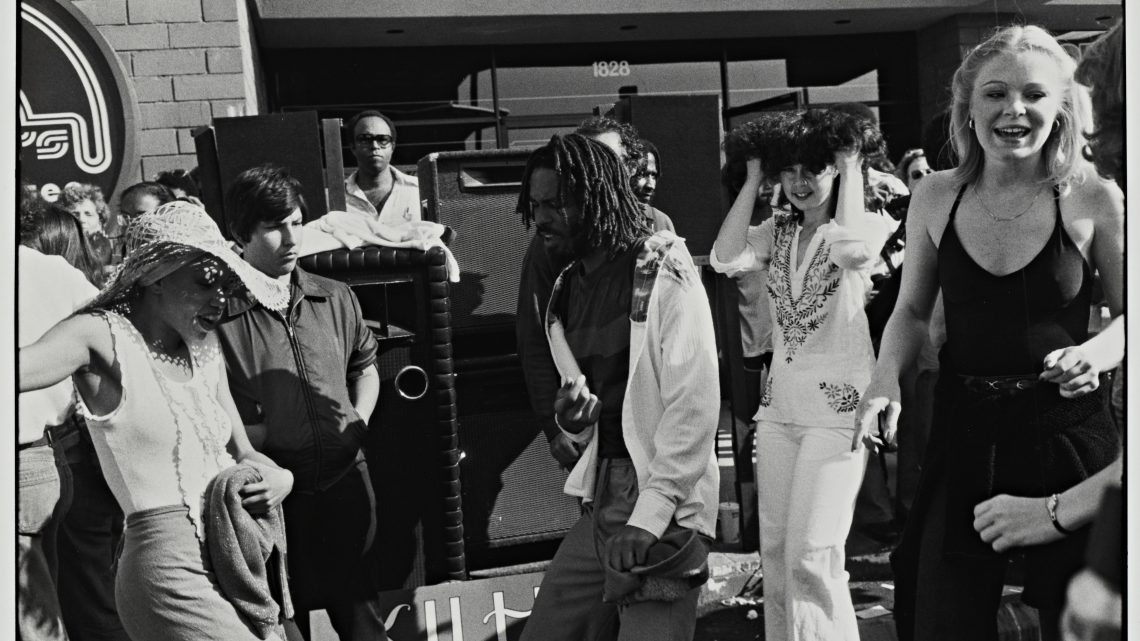

The push and pull between the commercial impulse for racial harmony and the contentious history of race relations is most fully realized by a series of videos containing archival footage. The videos, located on a viewing console, encourage one to sit down and work their way through the shorts, which include a compelling mix of mainstream media perspectives.

A 2014 Super Bowl commercial for Coke, #AmericaisBeautiful, epitomizes the commercial optimism found throughout the exhibition. The ad features a multilingual version of “America the Beautiful” and the lyric, in English, “America, America God shed his grace on thee.” In this commercial, a multicultural United States embraces and shares its bounty and God’s grace on all its citizens, even embracing the beauty of its many languages. It’s the antithesis of “English only” policies, which gained momentum in the 1980s, and the current anti-immigrant race-baiting of Donald Trump.

Still from Universal Newsreel, 1965. Courtesy the Internet.

With the swipe of a finger on the screen, vintage newsreels of the 1965 Watts riots come into view. The Universal Newsreel of 1965 titled “Troops Patrol LA: Damage Heavy in Coast Riots” features black and white images of burning buildings, eerily empty structures, left-over framing with fires inside the doors, hyperbolic B-movie music, and the noir detective voice-over narration of Ed Herlihy. His scripted voice looms large, creating a darkened view of the American dream, dramatizing a respectability squandered by punks: “one hundred square blocks were damaged by fire and looters”, “insurrection by hoodlums,’” “war torn city,” “hoodlums who stole everything from liquor to playpens.” The camera, in long-shot at street level, takes on the perspective of the city itself, burning as police push solitary rioters through the streets. The script, reminiscent of propaganda movies warning parents about the dangers of rebelling teenagers, resonates with an undercurrent of paternalistic fear mongering.

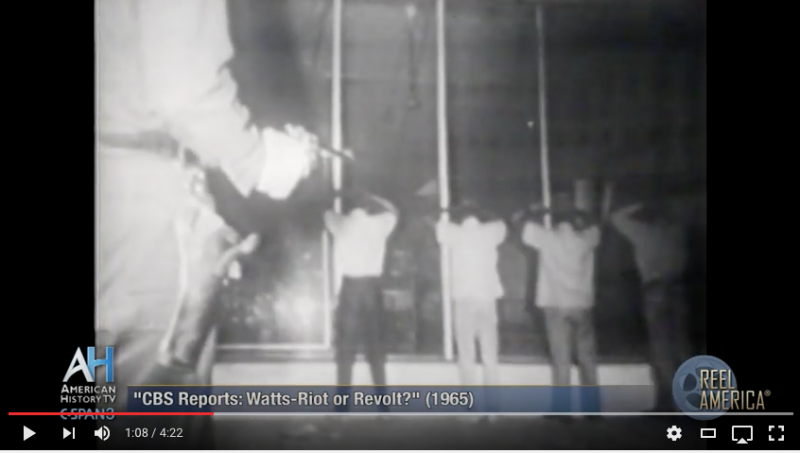

Still from CBS: Watts Riot of Revolt (1965). Courtesy the Internet

Another film on Watts, “CBS: Watts Riot of Revolt (1965)” opens with voices off-screen saying “Get the white man, get the white man.” Grainy black-and-white location footage swirls around a nighttime scene. Then a male voice-over begins, “It was the most widespread, most destructive racial violence in American history. White people driving through the riot area were considered fair game, whether young or old, men or women. Their cars were battered. The drivers stoned, kicked, and beaten and the cars were burned.” This news report attempts to give the viewer the whole story from the beginning: two young black men were stopped by a white officer for drunk driving, the boys’ mother was pushed and shoved. The television show notes: “over and over negroes repeat the charge of police brutality.” An interview with an African American lawyer poses the question of African Americans receiving due process for their claims of police brutality. He refutes the idea saying that the machine is broken.

The next interview is with Daniel Moynihan, Assistant Secretary of Labor under Lyndon Johnson, whose 1965 report “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” was one of the first major governmental analysis of African Americans. While the report was controversial for many reasons, Moynihan, in his interview is candid about U.S. history: “Remember that American slavery was the worst slavery the world had ever known. We can’t get that into our heads …There is no other slavery like it in history… segregation and the great humiliation of Jim Crow was a brutal assault on the personal integrity of the Negro male.”

Seemingly, in response to Moynihan’s comment and his thesis that the African American family structure was broken by slavery, the impossibility of African American males to integrate into society due to prejudice, and consequently the rise of the black matriarchy, a reporter talks to a young male Watts resident. The newsman, guided through Watts by a looter, comments that he’s experiencing, “a tour of the places he helped to burn as casual as a stroll in the park.” The young man begins his tour, “I threw a fire bomb, right in the front window…. Then we cry in the streets, ‘burn baby, burn’… We decided to burn this store because we felt this man had not been doing nothing but gaming on us, anyway,” his final comments, a succinct summing up the black experience.

Still from video, Rodney King beating, 1991. Courtesy the Internet.

On this same viewing console, silent excerpts from the 1991 Rodney King beating are brutal in their ghostly reminiscence of a lynch mob. The old video footage is grainy and pixelated, slightly distorting the image, but the circle of violence is clear, as are the hard kicks, unrelenting physical assaults, and sadistic domination by the police officers.

The news clips from the 1992 riots in South Central after the King verdict are much different in tone from 1965 reports. The footage is taken from a helicopter so there is privilege in looking down at the scene, a scintillating, omniscient point of view, watching cars being overtaken, bottles thrown, chaos below. It’s a cross between panic and carnival. The viewer, on their home televisions, can watch the destruction, pass judgment, and join the excitement without ever encountering the circumstances that created the anger. In 1968, Whitney Young commented on televised protests which had become “a kind of entertainment for millions of morally impoverished people who view the demonstrations of the oppressed on television sets in comfortable homes and then turn to other diversions, unmoved, uncaring. Their hearts are ragged, their decency tattered, their morals shabby. … These people too, these morally impoverished Americans, have to be rehabilitated.”[1] In 1992, television functions in a similar way, alienating the watched from the watchers, producing a nebulous moral connection between rioters of South Central Los Angeles and a nation of television viewers. In an unconsciously ironic moment, the news anchors comment that LAPD has prepared for this with extra money for overtime yet keep wondering why there is no law enforcement in view.

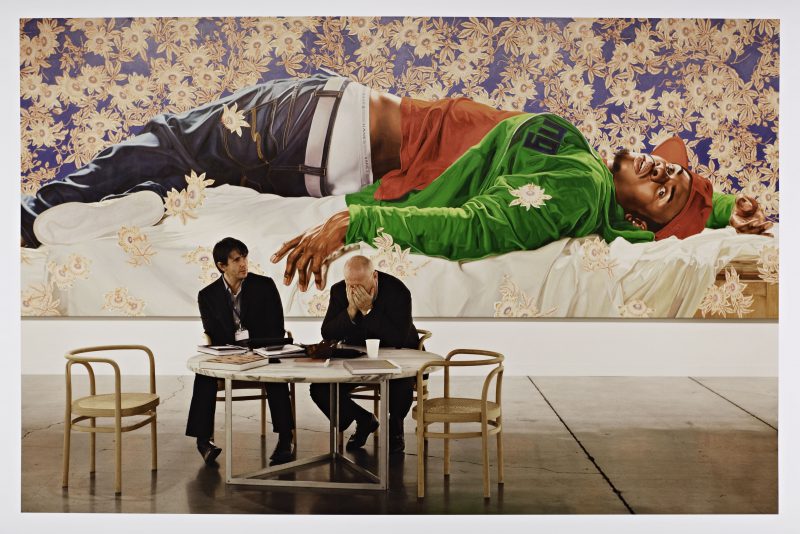

Installation view, Who We Be, Cantor Arts Center, 2016.

In the exhibition, these clips are mixed in with Benetton commercials and the now Mad Men famous 1971 Coke commercial. These commercials seem to be more about global commerce, the United Colors of Benetton and “I’d like to buy the world a Coke” than about multiracial America.

A vitrine features a row of magazines from the July 8, 1991 issue of Time to May 10, 2015 issue of the New York Times Magazine. Its cover reads: ‘Our Demand is Simple: Stop Killing Us.’ The sequence traces a tentatively hopeful July 8, 1991 issue of a multicultural American patriotism celebrating the 4th of July to the election of Obama to Ferguson to Black Lives Matter. Here we see the popular rise of multiculturalism and its failure to address the real, systemic needs of African Americans.

Lorna Simpson (U.S.A., b. 1960), III, 1994. Wood box, felt lining, and insert with lithographed image and text, three ceramic wishbones. Cantor Arts Center collection, Anonymous gift, 1998.23.1-4

In the works of art on view, some confront like Carrie Mae Weems You Became Mammie, Mama, Mother, Then, Yes, Confidant-Ha (2014) and Daniel Joseph Martinez’s Museum Tags: Second Movement (Overture) or Overture con claque-Overture with Hired Audience Members (1993), a series of museum visitor tags which spell out “I Can’t Imagine Ever Wanting to Be White.” Byron Kim’s CWLS or LSCW (1999), a series of small painted panels representing individual skin tones, subtly introduces the nuances of race and ethnicity. Lorna Simpson’s III (1994): three wishbones in a box of felt and wood is hopeful in its symbolism, but the bone must be broken and only the person who gets the bigger half receives their wish. The bones, made from bronze, ceramic, and rubber, are materials that would either be impossible to break, possibly shatter, or be stretched to their limits. So while she presents a folk tradition of the wishbone, it is cast into a form where it is impossible to use.

Andy Freeberg’s Sean Kelly (2008) most clearly synthesizes the an uneasy connection between the monied white world of art dealer Sean Kelly and the subject of artist Kehinde Wiley’s large scale painting Femme Piquee Par un Serpent (2008) from his Down series. The saturated image features a languid, young African American gangster, fully reposed on a pedestal covered by a white satin sheet. The lush floral background is slightly surreal with the flowers falling over the body: an uncommon setting for a black male body. Kehinde Wiley’s site described the images in this series as “prone bodies—some a product of the ravages of war, some contorted into erotic revelry, while others embody the majesty and severity of entombed saints” Freeberg’s photograph clearly shows how the commercialization of black bodies within the art world has been successful while Wiley’s actual painting points to a more ambiguous and ambitious vision.

Andy Freeberg (U.S.A., b. 1958), Sean Kelly, 2008. Archival pigment ink print. Cantor Arts Center collection, Gift of the Ann Jastrab Collection, 2013.5

Wee Pals, a comic strip by Morrie Turner, shows how a popular medium could function as a discursive space capable of containing commercial optimism within an historical context. This seems to be the overall question of the exhibition; can we be optimistic and also be responsible to our common history? Turner’s comics feature a cast of characters of different racial identities, but Turner is aware of this as a construction. In one strip, a character comments on having hyphenated friends. In some of the comics, Turner makes space for a segment of “Soul Corner” which features important historical figures like Cesar Chavez and Anna J. Cooper. Wee Pals, in many ways, seems to be the most successful at integrating the hope of a racially equalized America with honesty and realism.

The exhibition is based on Jeff Chang’s 2014 book Who We Be: The Colorization of America, and Chang acknowledges Turner’s importance in the exhibition and in his book. In the opening leaf, he writes, “To the memory of Ronald Takaki and Morrie Turner” and the first chapter, “Rainbow Power” is about Turner and Wee Pals. Chang’s book is an accessible, nuanced, and complex overview of representations of race, culture, and history and Turner’s ability to interject a sophisticated voice into a popular medium seems to be Chang’s paradigm.

Curiously enough, there is a new proposal to put Harriet Tubman, the 19th century African American former slave, abolitionist and political activist, on the $20 bill. This perhaps, exemplifies the mix of optimism, historical inclusion, commerce, and policy avoidance to its extreme. Instead of reparations or significant capital investment in African American communities and education, the government chooses to make money instead of giving it. If the Harriet Tubman bill becomes reality, we will have found a way to give money without giving money. It seems that white guilt works in mysterious ways and unexpected ways. The cultural unconscious wants to acknowledge the past but prefers representations of money to actual policies which would enable poor African Americans to enter into commercial world through education, job training, child care, health care, and housing stability.

The exhibition, in its mix of mediums and perspectives, asks the audience where we are now, in terms of race relations and how do we know where we are given the divergent aims of our sources of information. What are we getting from the news, from commercials, from the press, from artists, and from the comics? It’s never the same story twice, or is it?

—

[1] Franklin, Ben, “Protesters Call for Sharing of Nation’s Affluence by All”, New York Times, June 20, 1968, p. 30.