“She’s a thief of hearts, someone please arrest her!”

One sweaty summer I saw on Instagram that Jacolby Satterwhite and I were both in Miami, so I sent him a note. A few nights later I picked him up outside a party. As he hopped in the car I suggested we go to a trashy bathhouse in southwest Miami called Club Aqua. He laughed, “Put on Madonna—Thief of Hearts!”

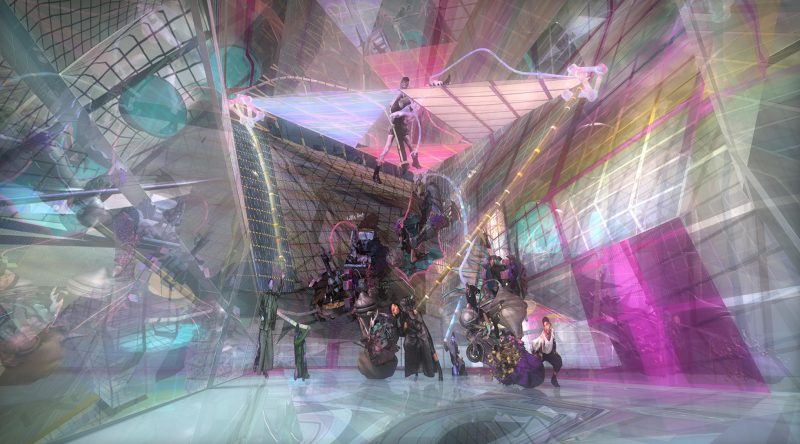

Just like that, I adored Jacolby Satterwhite, in the same way I immediately loved his art. Satterwhite is known for phantasmagoric animated videos in which he uses his own body to create gyrating architectures and mythological narratives—a 3D Hieronymus Bosch. We met back up in New York to discuss his background in figurative painting, his thoughts on digital abstraction, and the difficulties of using bodies as signs.

You came out of painting and drawing: What was your painting like, and what interested you in it?

When I was at the height of my painting investigations I was mostly influenced by New Leipzig school painters like Neo Rauch. And I liked South African painters like Marlene Dumas. I was really into figuration. I was also into classical painting, as well as Phillip Guston. Peter Doig is still one of my favorites. I have an eclectic range of interests. I am a formalist and I was interested in the medium, the viscosity of it—I was romantically involved with the tactility. I had a very romantic approach, but it was too romantic.

I approach my current practice with the mindset of a painter. I still mix a palette, but I no longer grab my palette and my palette knife and get my reds and oranges and just go ham—I don’t spend three hours on that anymore. Instead, I spend three hours building a digital palette, literally. Maybe that means changing the color of two thousand figures and sorting them. I build compositions first and write essays and then outsource other bodies, then I Google various random found-footage imagery, and then I work in Maya, a 3D animation program. I use all these variable and methods to generate storylines, to generate composition.

Factory Two, 2015. C-print, 45 × 80 inches. Edition of 2 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and Moran Bondaroff.

To go back for a second to your pre-digital moment: Were you interested in abstraction in painting?

I’ve always been interested in abstraction. When I was a teenager, I was deeply into the Bauhaus, and I read about all the corny stuff like Kandinsky. Then I got into Josef Albers and abstract sculpture like Lee Bontecou and Eva Hesse. I was interested in mid-century abstraction and formalism, then somehow segued into still-life paintings and got into Morandi. Then in my early twenties, I wanted to get away from rules and stuff, so I lost interest in the theory behind painting and the politics behind abstraction. I was trying to figure out an autonomous, apolitical voice as a painter so that I would have the freedom to live in my own meta-narrative. Now I don’t have to think about anything but my personal mythology; I build up my own lexicon and that is what makes me happy.

How do abstraction and figuration work differently in painting than in the digital work you are making now?

They are physical in different ways—the tactility is different. They are both sexual. Actually, the only difference is that they are different. They are so similar—I don’t feel like I’m doing anything different. I’m trying to make the same image I was trying to make as a painter; it just happens to move. My body is involved. Touch is way more involved.

Could you explain how touch works digitally?

When I was painting, I had 600 brushes, so there was a certain kind of physical labor that was immediate. When I make my videos I use a Wacom pad and trace my mother Patricia Satterwhite’s drawings in the 3D program. I spend a month building and sculpting her drawings and tracing the lines and zooming in on her graphite, really figuring out how to manifest her vision—it winds up being so analog. It’s not like I just insert something into a program and whoop it’s 3D. It’s not a magic trick; it’s very much about drawing, it’s very much about making a preliminary sketch. Then, after I’ve sculpted these drawings, I have to color them and do gradations and figure out what palette I’ll use. I might decide, “I don’t want tertiaries, I want neutrals,” or, “I want to deal with more muddy palettes.” So I color every single one of her lines while streaming Scandal or Entourage on HBO GO because the process is repetitive. Then I’ll ride my bike up north to the studio and spend a week with a bad back wearing twenty different leotards in front of my green screen. I have a purple leotard, an ochre one, a cheetah-print one: those are different characters, different colors, different bodies. I think of the leotards as a way to define my palette because of the specific ways color signifies when you see it in a video. Then I go back in Adobe After Effects and abstract the leotards: changing the ochre into a pink, changing the purple into a teal, building two thousand different characters who have different William Forsythe–style movements that emerge in the composition. My movements are based on composition because the way I build geometry is with squats and dips and twirls. If you look at my new compositions, these Boschian, Rubensian situations, they’re very painterly. They’re very much about space and trying to figure out the compositional curiosities I had as a painter—I don’t see it any differently.

Your new C-prints are eight by eleven feet. When you make an image at that scale, how does it relate to the person looking at it? When most people think of digital media they think of a computer screen, or maybe an animated film. But this seems to relate to a grander, almost billboard scale.

I’m exploiting Maya’s technology for getting crisp images at large scales. Working with this amount of detail is deliberate because it makes the image a time-based experience; there is so much to absorb and take in. The scale being eight foot by eleven feet, your eye has to travel in a certain way that requires time. An Agnes Martin requires your time, but in a different way; with this, you can’t consume everything without looking left, right, up, down, and arching your back and zooming in—it’s a very bodily experience. Because Maya can print things 84 by 60 inches at 400 dpi, I can really play with those potentialities of detail and space. I was trying to make paintings like this a long time ago—they were simpler than 500 bodies but they definitely had a certain kind of Polly Pocket, Final Fantasy aesthetic.

Leopard Interstate, 2015. C-print, 45 × 80 × 3 inches. Edition of 2 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and Moran Bondaroff.

Interstate 75, 2015. C-print, 78 × 60 inches. Edition of 2 + 1AP. Courtesy of the artist and Moran Bondaroff.

I’m interested in your relationship to drawing and what it means to re-draw all of your mother’s drawings. How do you learn from drawing as a process or tool?

I’m a colorist. I lose myself in my mother’s line and I can use her language as a vessel, as a backdoor strategy to indulge some surrealist tendency. She gives me a means by which to focus on color, texture, and space: I don’t like line necessarily, but when dealing with its actual construction, I think formalism is important.

What does formalism mean to you?

I think formalism is the foundation of art; for sculpture and painting and drawing, formalism just means line, color, shape, space, light—it’s like focusing on the objective component in order to build more subjectively. I really make sure that I have as many objective variables as possible before I start going into the juicy stuff: the content, the politics, the porn stars, and Trina. I want to build the most beautiful abstract, dense, and explosive space possible before I start to give in to my impulses toward perversion. I think that if you really dedicate yourself to the craft of things, the poetry that lives beneath it can come out, giving everything so much more agency and strength, and it allows you to feel more confident when making quick, honest gestures. I put so much labor in my work so that I can be very honest when I get to the actual idea. You could spend four months researching and researching and making up a manifesto about a certain conceptual idea and it could wind up being stuffy and suffocated and dead and dishonest. It’s like when you’re a dancer and you improvise movement for an hour, building up rhythms—it’s very direct and honest. I’m pursuing many ways to be direct.

How does your idea of abstraction relate to being direct?

That is the whole definition of abstract. In the 1950s, it was a very bodily thing: de Kooning with a big brush that slams against the surface and makes an “honest” mark—it’s visceral, it’s performative. It is what it is: it isn’t an illusion. It’s flat. I think the flatness in abstraction can yield truth.

Are you interested in truth?

I’m interested in my truth. I’m interested in my pleasure, and my pleasure is my truth. So if I make something that gives me pleasure, it’s true because I feel fucking good, therefore if you look at it you’re going to get some truth.

How do you think about the identity of “Jacolby Satterwhite” as a character in your work?

I’m a performance artist, so I’m naturally going to be a loaded presence in my work because I’m physically in it. All the metonymy of “Jacolby Satterwhite” is in the work. I use my background as one of the building blocks for my narrative.

How did you start doing performances?

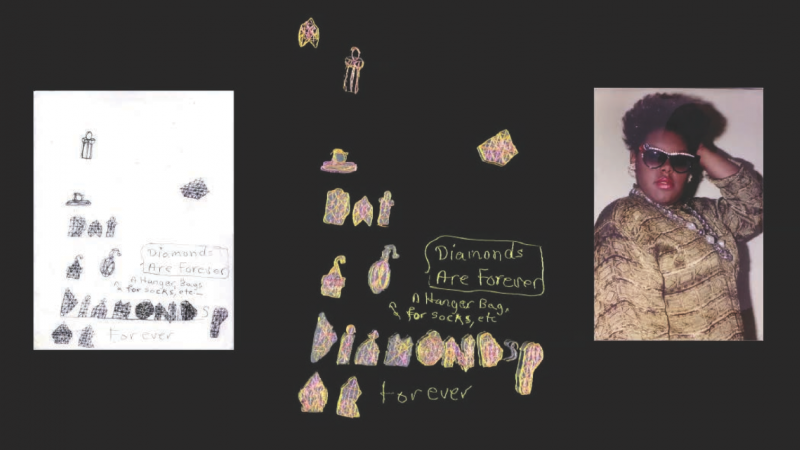

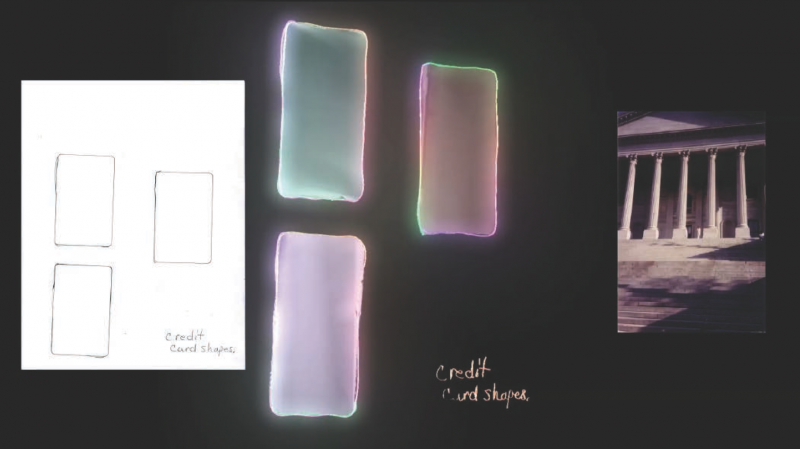

Really randomly, as an undergrad. I used to carry around my mother’s drawings. One day an instructor asked us to bring in something that we didn’t feel was art. I brought in this work I had made recently: my family photographs next to my mother’s drawings. I was interested in the synthesis between her drawings and what was actually happened in the past. She was doing schematics of her memories through objects, like the pocketbook that she hit her husband with in 1988; she made a drawing of the pocketbook and the mason jars that were next to it. So I thought to put family photographs next to those drawings. I was interested in that binary.

Then when I started really looking at the drawings I thought, “These are really interesting, I want to make these into a sculpture.” I made a costume based on one of her drawings—I sewed some Leigh Bowery thing. Then I thought, “You know, these drawings are kind of like performance scores from the ‘60s. They’re like Fluxus—they have words, the objects are like memories, and the photographs are like performance relics. Why not find a way to manifest these in the future as performances?” I was trying to physically manifest different aspects of the drawings: dancing in public in Central Park, Times Square, Philadelphia. I started doing these movement pieces and building installations that referenced the objects in the drawings. There were objectives: I saw the drawings as instructions for tasks. It was a failure but really provocative at the same time—there was something happening by trying to force these disparate ideas together, trying to pressure something that doesn’t belong to belong. I’m always trying to merge a cluster of ideas that normally don’t belong.

Then I went to grad school and we had more conversations about those videos and I liked the way the conversation was going. I liked that they weren’t talking about “history” and “politics”; they were talking about me. I liked the immediacy of my own body, which produced a discourse, so I decided to focus on the performances. Then I decided I really missed painting, so I taught myself animation. I bought After Effects with a tax refund check and started playing with footage I had collected of myself performing in the woods. I wanted to draw on top of the footage, basically to make it a digital painting. With rotoscoping and tracing frame-by-frame, I made these performative, animated/live-action videos that I really enjoyed. I love post-production. I love the magic and abstraction of digital media. At some point, through a lot of trial and error in the programs, I discovered I could trace Patricia Satterwhite’s drawings into these pipe forms and planes and actually manifest them into a landscape, and within that landscape I could put the figures. This was so important, because I could have my cake and eat it too: I could be the painter I always wanted to be, the performance artist I always wanted to be, and the music video person I always wanted to be—everything just came together. Then I started really going ham on it and studied 3D animation and the potentials of Maya—there are still so many possibilities.

Basically, there is an arsenal of language that I’m trying to intersect with the body, the performance, the painting language, the landscape language, and the idea of combining live-action and mediating it with animation. There is just so much going on and so many networks to negotiate. Putting it out to the public was a way of extending the frame, putting the characters outside of the world that I built and having them manifest a visceral form.

Did you study dance?

My brother was a dancer and I had a very dance-y family. I’ve gotten much more sophisticated with my dance style. I didn’t study it, but I went to a boarding school with a dance program, so I’d go to recitals and look at people. I looked at a lot of dance scores. I hung around with my voguing friends as a kid—they went to balls and stuff. The influence is real, but I didn’t start to hone in and become a better dancer, take care of my body, and go to the gym until I started doing these green-screen performances. I’m much better now than I was even a year ago. I’ve infinitely improved; I have restraint as a performer. When I’m in a green-screen video, I have a specific agenda with my movement; when you limit your movement with an objective, you have to become creative with how you move that arm from left to right. When you start to develop a range within limited movement, you become a better dancer, and that is what’s happening. I’m learning how to be a dancer through finding a system for my own style of dancing—it’s not voguing, it’s not modern—I’m building a style that fits the content of my work.

The Matriarch’s Rhapsody (still), 2012. HD digital video with color 3D animation, 43 minutes 47 seconds. Courtesy of the artist and Moran Bondaroff.

The Matriarch’s Rhapsody (still), 2012. HD digital video with color 3D animation, 43 minutes 47 seconds. Courtesy of the artist and Moran Bondaroff.

A lot of your work plays with the relationship between the physical body and the image of the body—e.g. between the aesthetics of online porn and that of actual sex. How do you see that dynamic unfold?

What I like about the physical body is that—whether it’s Trina or Antonio Biaggi or me or the random guy on the street—we all represent something. Our bodies are like a font; everyone has a specific representation of their identity and it’s very reductive: like “white male” or “camp diva wearing sequins and hair weave.” I think every body is a loaded essay; if I cast someone in my work, I give it some forethought. Using Antonio Biaggi for me was a very deliberate, meta thing. I wanted someone who is famous for breeding and bareback porn to go with the fact that I was breeding a new language in my work—the whole thing was a world-building video. All these things kept birthing. Landscapes kept manifesting. I knew my work was about to transition to a different place, so I wanted to make a piece where this guy inseminates me with a new language. After he comes in me, an egg comes out, and when it hatches, there are thousands of people inside. The older work was just me and my body in some obscure, eccentric space. But the more I make pieces, the more specific they get; I wanted a bareback porn star to birth that specificity. That is why I used him.

How do you think narrative operates in the films?

I concoct narrative in a surrealist way. An example of one process: I write a list of 30 items in my mother’s drawings. I’ll write: shopping cart, shoe, roller coasters, teacup, butcher-knife, tampons with robotic digital devices implanted in them— then I put them into Microsoft Word and I try to fill them in and make sentences out of that list, which makes absolutely no sense. Then I try and clean them up and allow that to guide the landscape I’m building in the animation. It’s my subconscious, honest space; what it yields, I don’t even really understand, but it definitely shows my tendencies, my repetitions. Then I have to negotiate how to make that concrete, to reify it. That is how I build narrative. I’ll observe a motif I’m interested in and then think, “You know who would be the perfect person for this particular idea, this particular thing that I’m repeating in this stream-of-conscious essay? Trina.” Then I pursue her and put her in the video. I take risks by trying to stay faithful to nonsense. To make nonsense sensible—that is to put it within a grid and try to sew it together—that process of making abstract video is similar to making an abstract painting: you make a bunch of marks and try and make them have harmony. I feel I’m trying to bring disparate languages together to build harmony in my videos.

The last thing I want to ask you about is sci-fi aesthetics or the conceptual apparatus of science fiction. What does it give you?

My work is futuristic, stylistically, and the medium lends itself to that. I do love fantasy. I’ve beaten every video game, those nerdy lock-yourself-away-for-300-hours kind of games. I was deeply into those and they shaped my image preferences. Also, the impetus behind fantasy is that you can deal with heavy politics if it’s masked in spectacle; everyone will just get lost in the spectacle. It’s like a scapegoat for really advanced ideas. Miyazaki’s Princess Mononoke was an AIDS movie but everyone thought it was about a wolf running through a landscape biting people’s arm and giving them lesions. That is what anime can do—talk about Hiroshima, bombs, and the bad economy. Spirited Away was about child prostitution, which you didn’t even realize because it was so magical; there were so many dragons. I am talking about a schizophrenic woman who has been homebound for 15 years, and I’m talking about meth heads and bareback porn stars and raunchy ex-stripper rappers, but putting them behind the lens of science fiction aesthetics to allow them to dissolve into something beautiful. I think that is what my science fiction does.

What do you think is being talked about in art right now that makes sense, and what do you feel has nothing to do with you?

I don’t think I have anything to do with being “post-Internet.” I don’t even know what that means. “Post-black” doesn’t make any sense either. Both post-Internet and post-black are basically saying: take politics and make something pretty with it—use the aesthetics as a device. But really, put me in any category you want—I think that is what art is about: everybody can be contextualized by each other. We are all living and breathing at the same time in the same city, and we are all drinking the same Kool-Aid whether we want to believe it or not. And when the history books are written there will be a spiderweb between A, B, and C. You can look at all these people who didn’t want to identify with each other, but at the end they were all in the same conversation, they were all like: “fuck de Kooning and Elaine—I’m me”; “fuck Warhol’s faggot ass—I’m me”; “fuck Philip Guston’s traitor ass—I’m me.” In the end, they were all drinking the Kool-Aid.