Ballistic poetry—on view at the art space La Verrière in Brussels until 2nd of July—aims to focus on the viewer’s unmediated experience. This celebration of intuition over explanation demonstrates itself, thanks to charismatic art pieces such as the ones by Marcel Broodthaers or Helen Mirra. I met with the exhibition’s curator Guillaume Désanges, one of the most creative France has at the moment, with the hope that this talk between a curator and an art critic—two mediators themselves—might lead to some readable contradictions.

Brussels, April 2016.

Marine Relinger: In my experience, when you have a good title the exhibition is interesting (and when it’s bad it’s bad). That’s how I shortlist the art shows I end up writing about. Ballistic Poetry is such a great one. I couldn’t resist.

Guillaume Désanges: [Laughs] Why not ? That’s a good idea.

Still the term ‘ballistic’ sounds kind of bizarre to me after the terrorist attacks in Paris, then Brussels…

Obviously there is no link. The project was conceived faraway before the events. You’re speculating. But in the art field, speculation can lead to beauty.

By curating a new cycle of exhibitions at La Verrière what do you mean to do when you “focus on the viewer’s unmediated experience”?

Somehow. The strongest art pieces, in my opinion, always contain a part of mystery. So the explanation that we can offer as experts should not rule the viewer’s experience. In other words, we can’t entirely define an artwork by explanations. So, yes, speculation is present and allowed, both for a curator and for a journalist or a visitor. It shouldn’t be forbidden.

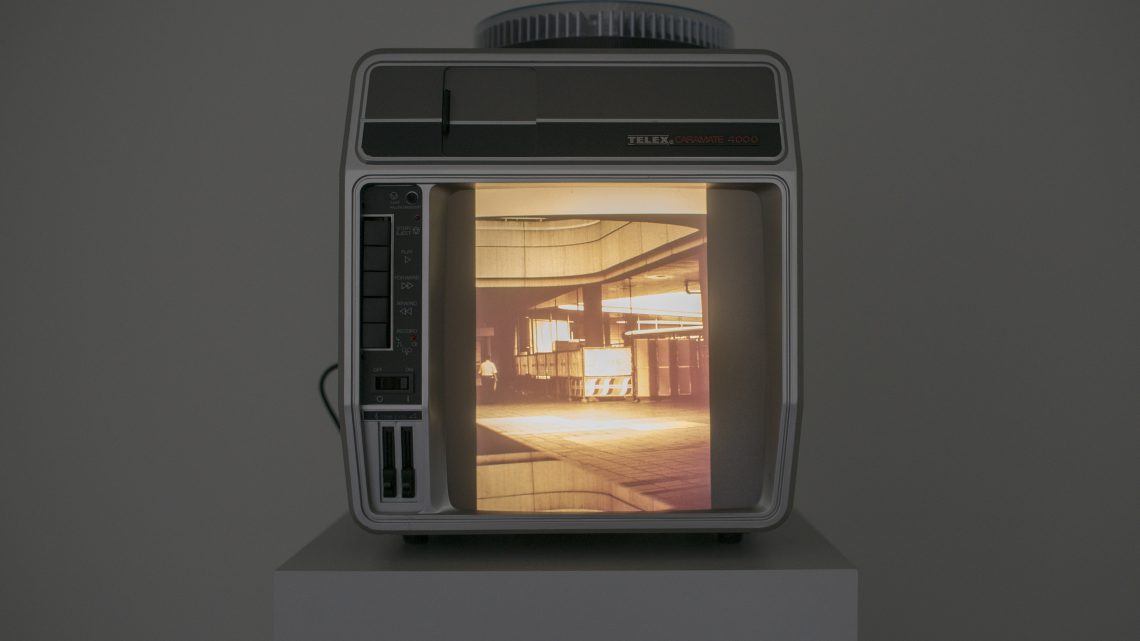

Poésie balistique exhibition view. La Verrière -Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2016 © Isabelle Arthuis. Fondation d’entreprise Hermès.

The French artist Jean-Michel Alberola says that what characterizes a work of art is its part of obscurity, its unspoken part which makes the viewer’s projection possible.He says, “if we cross the threshold then I rather fear that we lose the poetics.”[1] Is it this poetics what you try to save with the first exhibition of your cycle, Ballistic poetry ?

Yes. But I’ve chosen specific art pieces and certain types of programmatic artistic practices (eg. minimalism, conceptual art or the extreme rigor of objective photography), which are sometime negatively defined as hermetic. But the “hermetic” side of those process-oriented works has my interest, as it’s not selective at all. I mean the deal is the same for all viewers. The last thing I wanted is selection (as elitism). The philosopher Vladimir Jankélévitch says that “love is not a selection but an election.” Art is the same.

Then, the exhibition focuses on artworks based on precise and systematic protocols; whose theoretical pre-suppositions, though pregnant, are nonetheless masked by the form itself: works that draw straight lines in space, and in the mind. Works based on a calculated impact. It is what I call “ballistic.” But if the protocol is necessary, it is not necessary to know what the protocol is because those forms are made to be felt rather than understood by the viewer. Then, superficial discourse fails to ‘paper over’ the vertiginous abyss of non-comprehension. It is what I’ve chosen to call “poetry,” but I might call it also mystery, opacity, emptiness, distance… Or obscurity as Alberola said.

About 20 artists are gathered in the exhibition. And, well, it’s refreshing; it is an unusual mix. We go through conceptual and minimal works such Marcel Broodthaers’s or Helen Mirra’s, an autodidact named Hessie, or Dominique Petitgand, who composes sound works, as well as contemporary poets…

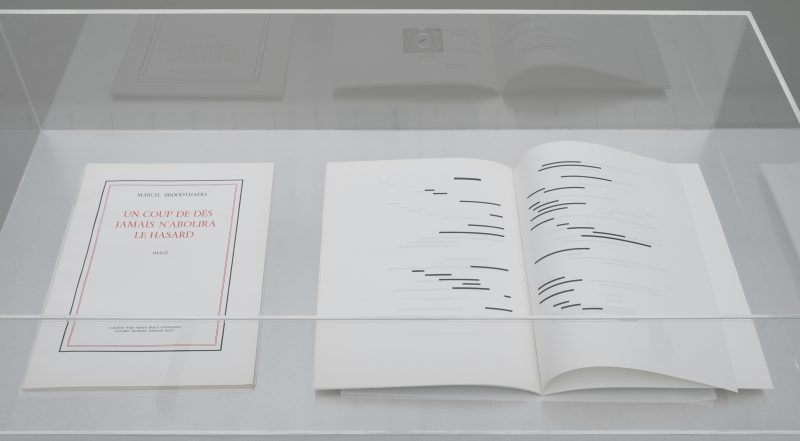

That’s the point. I’m not interested in “artistic categories” or making a flawless, rather standard list of names as a curator, like a nice bouquet of flowers. I try to question artworks in new ways. Here I bring together artists from different generations and expressive worlds, but they’re united by their process-oriented, critical approach. By adding texts by poets such as Christophe Tarkos and Mark Insigel, we focus on the link between programmatic artistic practices and radical “still” poetry, conceived to show rather than tell. In there, Marcel Broodthaers—both poet and a major artist of his time [the second half of the 20th century]—is like a father figure. His work presented here—Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard—is an exact reproduction of the eponymous poem by Stéphane Mallarmé, where each word disappears covered by ink, reducing the original text to its essential structure and layout.

Marcel Broodthaers, Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard, 1969 Original edition on transparent mechanographic paper Wide White Space Gallery, Antwerpen Galerie Michael Werner, Köln © Estate Marcel Broodthaers

I liked it, but some processes are far less perceivable, for instance, with the works by Helen Mirra, which consist of thin strips of colored fabric where she inscribed entries for her personal index, compiled for her own reading of the theoretical work Reconstruction of Philosophy (1920) by the American psychologist and philosopher John Dewey. Or these four delicate blades of glass standing up against a wall, their height and width calculated to be on the edge of the breaking point, designed by the French sculptor Guillaume Leblon. Sharp forms, as you said, but also an elusive process that makes those works very suggestive…

Happy to hear you’ve liked it. The latter, Leblon, is a young artist born in France in 1971 who lives and works between Paris and New York. He experiments widely, with diverse materials (sand, stone, wood, brass, china clay…) and techniques, and with space itself, to create ‘landscapes’ rigorously shot through a kind of latent brutality. He practices a personal archeology of sorts, since he keeps salvaged objects in his workshop for extended periods before putting them to use. In front of his work you have those by Hessie, who I am very happy to show in this context. She was born in Cuba in 1936. She has been practicing for a long time but her little-known work is gradually coming to light. Among the variety of techniques she uses, embroidery constitutes the bulk of her output. She creates very systematic compositions of repetitive abstract motifs in white or colored thread, on ecru cotton. The series, featured in the exhibition, uses typewriters to write in cotton, recalling formal experiments of concrete poetry.

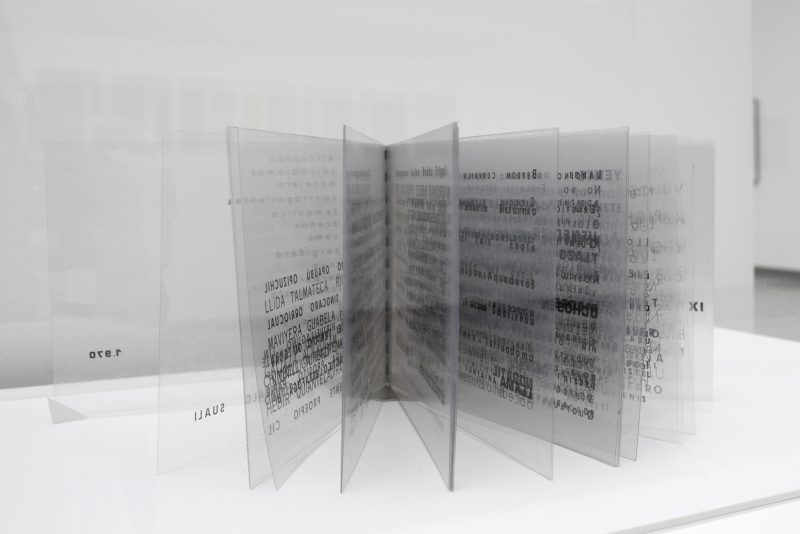

Isidoro Valcárcel Medina, El Libro transparente, 1970 Tranparent plastic sheets Courtesy the artist

In previous exhibitions you plunged the audience into the dark or you decided to put a large selection of artworks in relation with the topical events of the past decade, in order to question the purpose of art, which systematically reflects the historical context. You have also turned your conferences into performances.[2] You’re seen as a ‘creative,’ who challenges the traditional way of curating. Would you see yourself as experimental or dissident?

I would say experimental. And I’m far from the only one, if you think about curators such as Hans-Ulrich Obrist, Jens Hoffman, Anthony Huberman, Vít Havránek or the WHW (What, How [and] for Whom) group, just to mention some that come to mind. I am not against the institutional way. I work for it. And I do not trust people who claim to break with the institution, the structure and are often too obsessed by it. But if art experts don’t criticize their own practices, who will ever do that? I simply call them into questions, as institutions and conventions are not evidences. I keep questioning evidence, not existence. When I say I’m interested in the critique of institutions, I first keep in mind that there are so many art exhibitions. My question is always why should I add a further, how can I justify it? Often my students are told what to show and how to show it, but I ask them “why”?[3] It’s an uncomfortable question. For a curator, it can lead to the paradox of asking the very necessity of showing.

Roland Barthes wrote that when he postulates a paradox, it’s to free himself from a doxa (a popular opinion). But then the paradox turns bad, becomes a new concretion, becomes itself a new doxa, and he has to seek further for a new paradox. I feel this sentence fits your way of thinking and making choices…

I feel close to any thinker who proceeds towards a theory of chaos, such as Stéphane Mallarmé, Friedrich Nietzsche, Georges Bataille, then Roland Barthes, who wrote also about the “fécondité des contresens” (where he underlines how a rigorous subjectivity can be fruitful). Because at the end, there is no truth about art, no art history that would be right. Some people have told me that, given that I am seen as a “creative” curator, I may be indulged in doing unusual proposals. But, they say, there are more scientific ways to do curating. I don’t agree with that. I think every art exhibition is fiction, narration. All institutions, sometimes under the guise of objectivity (and authority as well), are fictional and narrative models that can be overthrown.

For instance, when I visit the “Galerie du Temps” at the Louvre-Lens museum—which narrates the history of art from antiquity to the 19th century—I notice that the story suits the imperialist French history. We know that we have our “roman national,” and that the art history is part of it. Acknowledging my subjectivity, and working on it, I try to question the dominant narrative in art. Well, in life too. It’s the same. I remember once I told a psychoanalyst that I think even psychoanalysis is fiction. She replied something appealing: “You’re right, we live according to fiction patterns. But some people need psychoanalysis because they are living in a fiction that’s not their own.”

Poésie balistique exhibition view La Verrière -‐ Fondation d’entreprise Hermès, 2016 © Isabelle Arthuis. Fondation d’entreprise Hermès

So you want defy the question of the point of view. But when you talk about the visitor’s “unmediated experience,” you keep telling a story. You consider art in this context of reception. You wrote a poem about it, used as an introduction. And there are traditional labels with names, titles, and some contextual information about the work hanging on the walls. So when you speak about “unmediated experience” you keep doing mediation. Why not “faire silence”?

At the beginning I didn’t want labels, but I talked with my collaborators and I changed my mind. If the show was conceptualized for insiders, initiated people, there would have been no labels at all, and then it would have been an interesting experiment. But at La Verrière, open to everyone, I’ve decided to display some information. Again the discourse is about the perception itself, so it’s an invitation to think about the subject. And I explain I work on my own subjectivity, even if I guess it doesn’t mean it’s personal. I guess subjectivity can be shared. Also, to make it silent could be an opposite trap. It would forbid sharing, that is the base for reflection. At the end, an artwork is polysemous, so it can be featured in different contexts and narrative patterns. We can speculate but very carefully. But we don’t have to ban speculation (it just means to hide). So I admit it, I am subjective. I propose “possible stories” that don’t claim to be THE great story of the art history.

But I like to communicate too much, to share my love for art. It would be difficult for me to become silent. And I guess it would have been something weak (even snobbish). But I will try to be less discursive in this cycle of show. My former boxing trainer, Christian Michel, who’s a model for me, used to fight without gloves, telling that the best fighters are the ones who don’t really hurt the opponents. But he also used to say something beautiful: “You still need to hit them. It’s a form of respect.”

—

[1] Interview by Léa Bismuth, In detail with Jean-Michel Alberola, ArtPress N°431, mars 2016, p.49-51.

[2] Guillaume Désanges, A History of Performance in 20 minutes, 2004.

[3] Guillaume Désanges is teaching at La Sorbonne University in Paris and at the Ecole nationale supérieure d’arts de Paris-Cergy.