The same week the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art rolled out its new addition to the press and favored followers, their crosstown contender, the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, was caught up in yet another crises of confidence, with two members of the Board resigning in the wake of President Dede Wilsey’s latest flagrant foul. Asking her Board to pony up $450,000 to cover the contested separation pay of an employee was just too much for the departing duo to stomach. It is but the latest example of civilian checkbook chutzpah overpowering the scholastic standards of a cultural institution.[1]

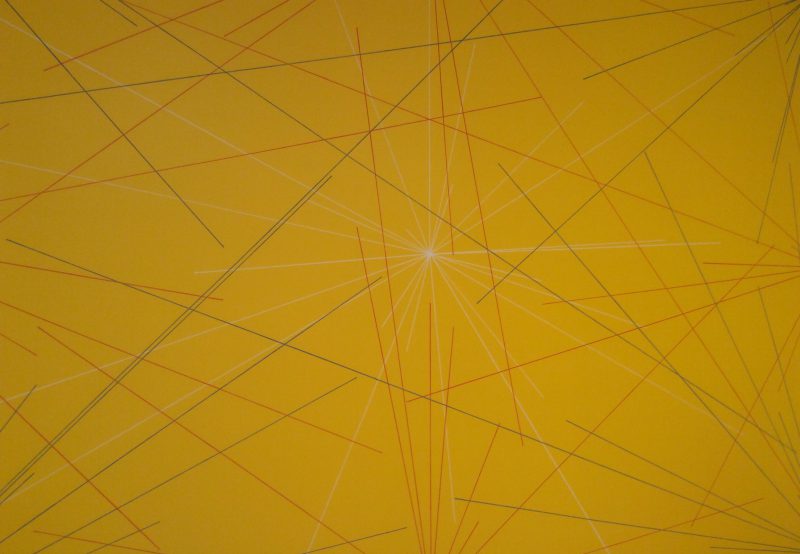

Sol Lewitt, Wall Drawing 280 (detail), January 1976. Graphite, crayon, and yellow acrylic paint on wall. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

Art is all about money these days, and what’s new? Artists have been dealing with patrons since some pie-in-the-sky caveman started sketching on rocks, the warrior class coming in and throwing him some hard-won meat every once in a while to keep the buffoon going. He was a source of amusement. It was a meager investment. And it turned out that there were those beyond the confines of the cave wanting to come in and see what all the commotion was about and willing to fork over a few pig knuckles to the ruling warriors of the roost for the privilege of doing so.

The newly reopened San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is letting children and young adults under the age of 18 into the sanctum for free. It helps to get them hooked, and nudges them into becoming desirous of the goods on display. They should be. Don’t they know what those things sell for? It cost a not-so-small fortune to reinstall the expanding collections in the big new rippling white building ($610 million), but I have no doubt whatsoever that the works housed within are worth tenfold more. Unfortunately, the artists aren’t being thrown much meat these days, while the financiers and grand merchants grow fat on the whole hog.

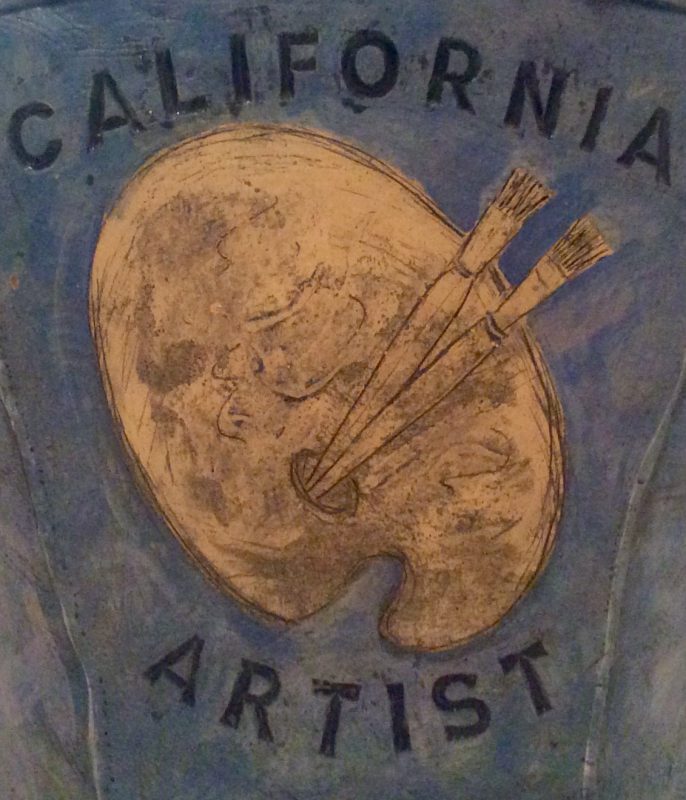

Robert Arenson, California Artist (detail, rear view), 1982. Stoneware with glazes. Photo: John Held, Jr.

This is not to say the artists don’t get something out of the bargain. They get their scratches and scrawls placed in a cathedral like setting validating their heroic struggle through years of deprivation. But more often than not, the validation originates with the warrior class having the wherewithal to facilitate their taste, not with the institutional academicians ill-equipped to foray into the marketplace and compete with these titans of industry.

Sometimes, it all works out. If you’re lucky, like Agnes Martin, beloved by both the warrior and scholarly classes, you get a quaint contemplative alcove to yourself at the end of long hallway, a custom-made upholstered bench placed in the center, assuring attention to your mood altering works. This small and intimate setting alone almost compensates for a three-year shutdown of the museum, which now houses the expanded collection.

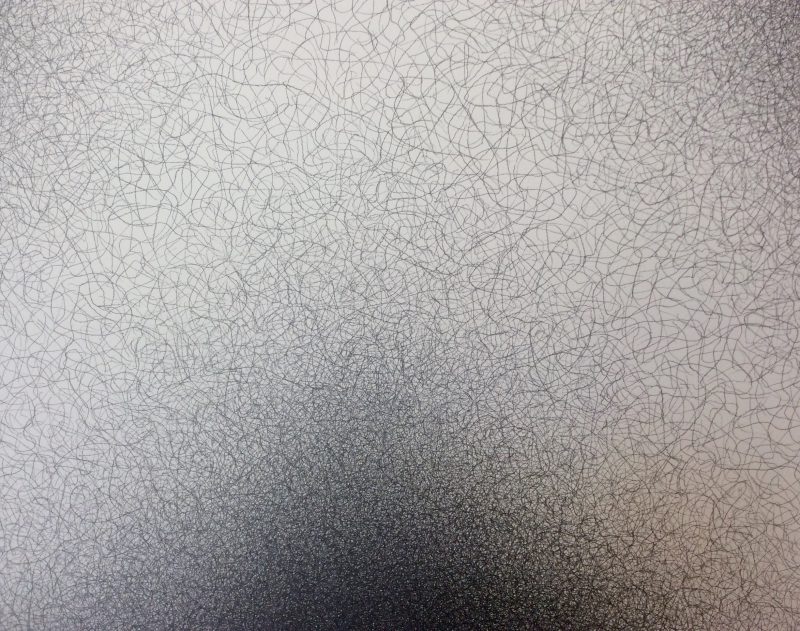

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 273 (detail), September 1975. Graphite and crayon on seven walls. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

The late Sol Lewitt has it even better. There are whole rooms and hallways of his wall drawings. And he didn’t even have to do them. He conceived of them, and after his death there were those willing and able to carry out his instructions. They are timeless works by a departed artist, who devised a strategy in defeating entropy. It’s a lot like getting the last laugh. But those of us who remain get the joke, as it generates one of the more powerful environments in the cathedral.

Sol LeWitt, Wall Drawing 1247 (detail), August 2007. Graphite on wall (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

You’ll see old favorites in roughly the same configuration you saw them before the closure. There are the familiar roomfuls of works by Clyfford Still and Paul Klee. Jackson Pollack’s signature work Guardians of the Secret, still stands as sentinel. Duchamp’s urinal remains resting comfortably on its pedestal. Arneson’s iconic California Artist persists in its stoic stance. A Rauschenberg here, a Ruscha there.

Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, 1917/1964. Ceramic, glaze, and paint. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

Post Bay Area Figurative painters, Robert Bechtle, Robert Hudson, Wayne Thiebaud and William T. Wiley, continue anchoring their portion of regional cultural legacy. But there is also an expanded version of the mid-twentieth century California canon with the addition of 1970s conceptualists Bruce Conner, Terry Fox, Howard Fried, David Ireland, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Tom Marioni, and Martha Rosler comfortably installed in a room of their own. Paule Anglim, the late San Francisco gallerist, who sponsored these artists, also gets her due, with a sentimental placement of her portrait painted by her long time employee, Travis Collinson.

Educational screen featuring San Francisco artist, Robert Bechtle.

(Photo: John Held, Jr.)

Richard Serra, Gutter Corner Splash: Night Shift (detail), 1969/1995. Lead.

Let me be blunt. I may be critical of the continuing intrusion of financial impact on the world of art, but I admire the local moneymen, the museum staff, and the architects for fashioning a showcase for contemporary art without parallel in the United States, including New York’s MoMA & Whitney. Yes, there’s the Centre Pompidou in France and the Bilbao in Spain, but never have great works of art been granted the largesse in which to exhale their languid elixir like those installed at SFMOMA. Here they breathe.

The exhalation from the works have already seeped from the space they inhabit. Just across the street from the new entrance on Howard Street, Gagosian, the largest gallery conglomerate in the world, has opened an outpost, hoping, one presumes, to capture the overflow of wealth that the new SFMOMA expansion signals. John Berggruen Gallery, one of San Francisco’s oldest and most respected artistic showcases, has also followed suit, raising its profile in a new space to open next fall, basking in the shadow of the Snøhetta-designed SFMOMA, that has already redefined the cultural landscape of the neighborhood.

Dan Flavin, The Diagonal of May 25, 1963. Blue fluorescent light. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

There was sure to be some controversy in such a bold endeavor. Overheard several times was the comment that there was just too much emphasis on German art, with several galleries devoted to Sigmar Polke and Gerhard Richter. Some feel the work already seems dated and holds little significance or local interest, but others have raved over the grouping of monumental canvases. Ditto Jeff Koons’s controversial works of kitsch, which some abhor and others adore. The “cruise ship” shell of the building’s exterior elicits both wonderment and bemusement. Entering into a somewhat unusual contract with the Fisher family (their works are on loan to the institution for 100 years, and every decade an exhibition from the collection must be mounted), and the closure of the museum for three years, while the Snøhetta-designed expansion renovated the original Mario Botta building that opened in 1995, adding 170,000 square feet of new gallery space, only expanded the cacophony of opinion surrounding the new structure.

Los Angeles critic Carolina A. Miranda decried the Fisher family’s choice of talent. “It is also an oppressive testosterone-fest. By my count, the fifth floor Fisher galleries don’t feature a single work by a female artist. The fourth floor drops in works by Joan Mitchell, Lee Krasner and Agnes Martin, but these bookend what is essentially more dude art.”[2]

Ruth Asawa, Detail of hanging wire basket. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

On the other hand, unmitigated praise was heaped on the reopening by Rev. Malcolm Clemens Young, Dean of San Francisco’s Grace Cathedral, who views the expansion as, “a great spiritual opportunity for the Bay Area.” After lauding John Cage and poet/ceramic artist M. C. Richards for their “spiritually informed philosophy for creating and experiencing art,” he concludes that, “The new SFMOMA will offer many opportunities to find our common center, to overcome our ego, to experience transcendence and to wake up to new ideas of who we are.”[3]

Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, Geometric Apple Core, 1991. Steel, polyurethane, and latex paint. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

In the vastness of the expansion, there are many rooms for many artists. The inaugural rollout of the Fisher Collection contains five exhibitions encompassing 260 works. Occupying the fourth floor, “Approaching American Abstraction,” highlights the works of Agnes Martin and 26 works by Ellsworth Kelly. One floor up, “Pop, Minimal, and Figurative Art,” features the “dude art” of Carl Andre, Chuck Close, Dan Flavin, Philip Guston, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Roy Lichtenstein and Claes Oldenburg (the SFMOMA press release omits Oldenburg’s collaborator Coosje van Bruggen, although she is cited in the exhibition text). “German Art after 1960,” resides on the sixth floor, while “Alexander Calder: Motion Lab,” is on the third floor, with “British Sculptors,” on the fifth.

Mark Bradford, Thievery by Servants (detail), 2013. Mixed-media collage on wood. (Photo: John Held, Jr.)

That’s probably enough art to fill most museums in the country, but there is much more. Hoping to capitalize on the generosity of the Fisher family, SFMOMA has launched a “Campaign for Art,” exhibiting 600 works that have been promised to the museum by other area collectors. Four exhibitions highlight these works, including, “Modern and Contemporary” (Floor 4), “California and the West: Photography from the Campaign for Art” (Floor 3) “Contemporary” (Floor 7) and “Drawings, Part 1” (Floor 2).

Haven’t got your fill yet? If you’re a fan of photography, SFMOMA has your mojo. The Pritzker Center for Photography highlights 180 years of photographic history drawn from the museum’s collection of 17,800 works dating from 1839. Unfortunately, this is the swan song for much-respected senior curator Sandra Phillips, who will become the museum’s first Curator Emeritus when she retires in June. She leaves behind “the largest gallery, research and interpretive space permanently dedicated to photography in any United States art museum.”[4]

Besides the art, there is plenty else to behold. The new addition is fairly minimal in its design. I think that’s a good thing, as too many architects have placed their new art museums above the service of the art within. Here, nothing clashes with the art. Some have reacted negatively to the interior of the building, comparing the finish to Ikea-like minimal design. I like that. And I like the fact that the architects have hinted there is life beyond the art, opening the building to The City by virtue of terraces that provide sweeping views of urban life. There are wonderful panoramas to behold—in the manner of New York’s High Line. Just as the new Whitney anchors the end/start of the High Line’s mid-level views, so too does SFMOMA’s new addition, providing a public outpost in which to view the San Francisco cityscape in a perspective previously only afforded to office workers in their towering buildings.

View from SFMOMA terrace

(Photo: John Held, Jr.)

The new structure also brings the outside in, by the inclusion of a “public living wall,” (29’ 4” tall and 150’ wide) on the third-floor Pat and Bill Wilson Sculpture Terrace, composed of more than 19,000 plants and 37 species, 21 of which are native to the area. It’s an abstraction come to life, and it’s one of my favorite works in the museum, because really, what’s the difference in enjoyment between an horticulturalist’s placement of living breathing fauna and an artisan’s attention to detail in an assemblage composed of discarded consumer goods?

There is much more to come, and it signals the new international clout SFMOMA has achieved. “Bruce Conner: It’s All True,” organized by SFMOMA, opens October 29, 2016, after premiering at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (July 3-October 2, 2016). With more than 250 works included in the exhibition, it is billed as “the first complete survey of Conner’s work.”[5] After the SFMOMA run, it travels to the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid. Conner’s multifaceted works, ranging from film to nylon stockings to inkblots have long been a benchmark of San Francisco countercultural art. Through the attention the SFMOMA expansion has secured, his work now has an opportunity to penetrate new ports of call. There will be other such bright prospects ahead afforded by the enlarged scale and increased reputation of the institution.

The expanded SFMOMA opens for free on Saturday, May 14. Visitors having timed tickets can secure entry at 11 a. m. after several hours of ribbon cutting ceremonies and remarks by museum and civic dignitaries.

—

[1] Matier & Ross, “Dede Wilsey Pressured to Reimburse SF for Museum Money Payout,” San Francisco Chronicle, March 15, 2016)

[2] Carolina A. Miranda, “SFMOMA Sneak Peek: More Space, More Dude Art and an Ellsworth Kelly-Agnes Martin Surprise,” Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2016

[3] Malcolm Clemens Young, “In My View: SFMOMA Promises Chance for Spiritual Awakening,” San Francisco Examiner, May 3, 2016

[4] The Pritzker Center for Photography Fact Sheet,” SFMOMA, 2016.

[5] SFMOMA press release: 2016 Advance Exhibition schedule