Theodora Varnay Jones: Fugue

Don Soker Contemporary Art Gallery

2180 Bryant Street Ste.205, San Francisco, CA 94110

May 7 – June 18, 2016

San Francisco’s art galleries, artists, and art stores are disappearing because of unaffordable rents–we all know this. The city’s beauty, its über-development business climate, and the tech industry explosion have caused an economic earthquake that has fundamentally changed the face of San Francisco. The delicate ecology of the arts and small businesses in San Francisco is being destroyed, and it may not return even if the pro-business Mayor is voted out or the tech bubble bursts. Working artists, small gallery owners, and businesses have been served notice: to get out of the way. Having an art studio, gallery, or even a bookstore has become an act of resistance or even civil disobedience. At the same time, the largest contemporary art museum on the west coast, SFMOMA, reopened on 3rd Street and mega-gallery Gagosian will open a branch across the street. Many small galleries closed; some fled the well-known gallery complex at 49 Geary Street for Portrero Hill, or to Oakland; some moved to the new Minnesota Street complex, a kind of temporary art life boat created by venture capitalists and art collectors, Andy and Deborah Rappaport. The San Francisco Arts Commission conducted an artist displacement survey last year to try to track the loss of artists from the City, and their survey confirmed that 70 percent of those artists interviewed have left the City or are or have been displaced. The anti-eviction mapping project features personal narratives of longtime residents being forced to leave. It is currently part of a larger current exhibition at Yerba Buena Center, Take This Hammer, which addresses the arts and social activism. Those that stay cite the generosity of their landlords, foundations, City programs, family wealth, or just plain luck.

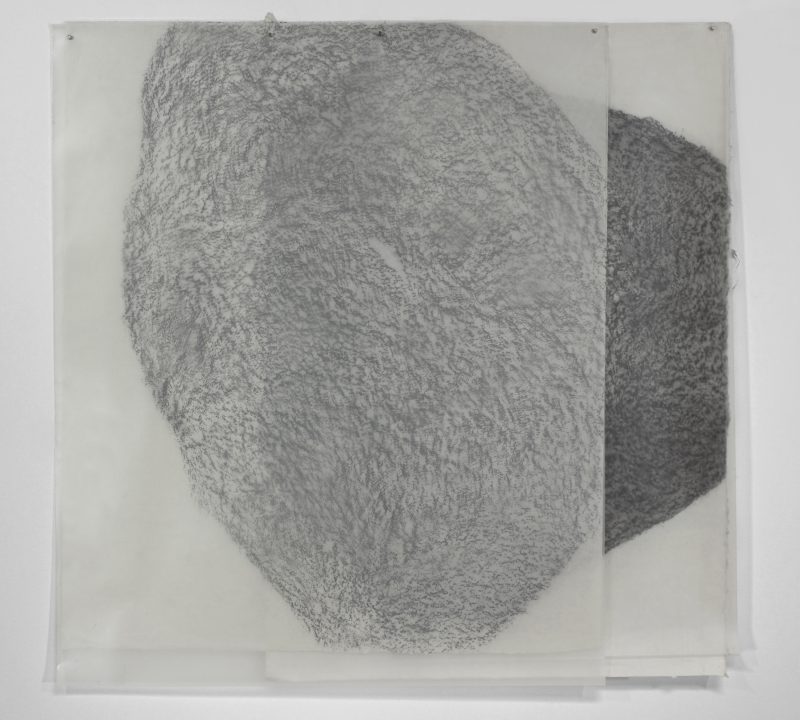

Theodora Varnay Jones, F-3B, 2015. Frottage (graphite on vellum), 25.5” x 27”

Don Soker, a gallerist for over 40 years, has had to move three times, from 49 Geary to a raw commercial space at 100 Montgomery Street and then to his loft in the Mission district he shares with his partner, the artist Theodora Varnay Jones. Varnay Jones redesigned the space to accommodate her studio and the gallery, and together they have created one of the most intimate and beautiful art spaces in San Francisco. It is called Don Soker Contemporary Art Gallery, and it is where I saw Varnay Jones’ new show, Fugue.

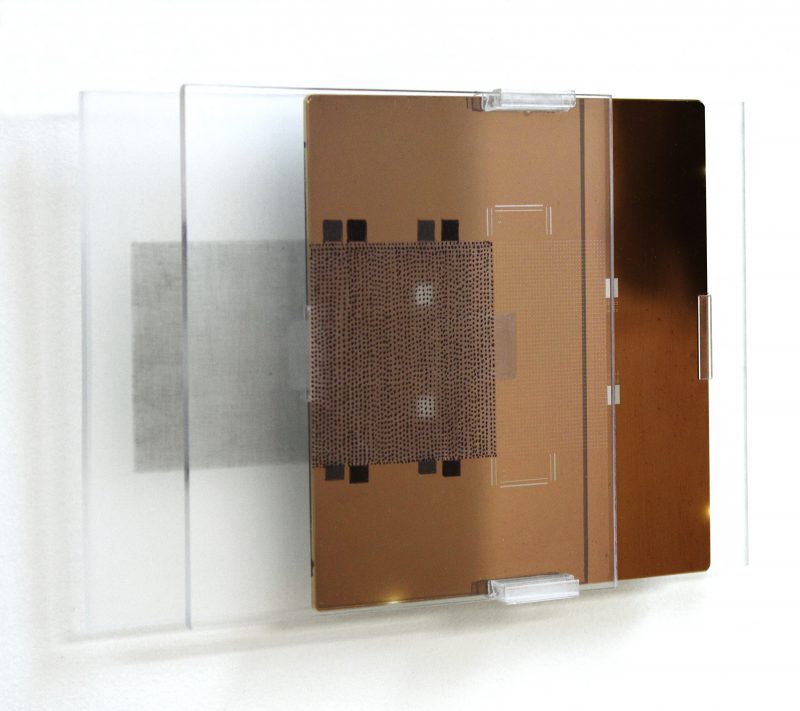

Theodora Varnay Jones, Nano-1, 2016. Glass wafer, sanding, graphite and sharpie on plexiglass, 5” x 8” x 1”

All the works in the show are in grey scale: black, white, silver, and grey. Varnay Jones was born in post-war Hungary and came to the U.S. in the 1970s. I like her Beckett and Camus meet wabi-sabi sensibility. I like how concrete, how physical, her work is: wadded daily newspapers, a tree stump rubbed with graphite. On one wall are numbered frottage pieces, begun at the Lucid Art Foundation Residency in northern California last year, that were made by rubbing graphite onto sheets of thin Japanese paper or thin-to-transparent industrial materials like mylar and velum and thus picking up the imprint of tree stumps, large stones, and unidentifiable found objects. To create this series of veiled drawings, Varnay Jones layered the sheets of rubbed images, thus creating skins of time and memory. The newspaper pieces come from Metamorphosis, a series from a 2010 residency at San Jose’s ICA Print Center; they show the same crumpled newspaper a la Wallace Stevens’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Two small pieces titled Nano are from another series Varnay Jones created from discarded silicon wafers she found after touring Stanford’s Nanotechnology Lab in 2014.

Theodora Varnay Jones, F-5, 2015. Frottage (graphite on handmade Japanese papers, polyethylene films), 42.5” x 43.5”

The show’s title, Fugue, seems to refer to both the musical form and a dissociative state of mind. A musical fugue, seemingly unbeknownst to itself and despite its strict rules of composition, may unfold as if it is a fugue state: wandering, adopting new identities and then promptly forgetting who it is, a state not unlike San Francisco artists facing market forces. We find this presented in the large installation, Narcissus.

Occupying floor and ceiling, the piece’s mirrored surfaces, which appear to be opened like a succession of books, face each other, and thus the piece reflects itself, and the room, and the viewer: when you step up and look at yourself, it’s as if the piece says, “Here you are, back again: endlessly looking . . . “ You meet your own gaze, in this seductive and dangerous pool of past, present, and future. In the frenzy of contemporary San Francisco, even Narcissus is an endangered species.

Theodora Varnay Jones, Narcissus, 2016. Site specific installation, mirrored plexiglass, wood, floor 12” x 14’ X 5”, ceiling beam 5.5” x 14’ X 5.5”