Laura Poitras: Astro Noise

Whitney Museum of Art

99 Gansevoort St, New York, NY 10014

February 5 – May 1, 2016

Laura Poitras’s first solo museum exhibition occupies the entire 8th floor of the new Whitney Museum, designed by Renzo Piano and overlooking the Hudson River. ‘Astro Noise’ refers to both the universe’s invisible light and an encrypted file she received from “Citizenfour,” the anonymous handle of NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden. As I rode the L train to the new Whitney Museum, most passengers sat transfixed by their iPhones, and though lamenting the mesmerized public has become cliché, I think it bears repeating: when you watch It, It watches you. Tracked by GPS and Facebook accounts on our “personal devices,” our digital choices leave Internet fingerprints that, little by little, erode our privacy all in the name of convenience. Her 2014 film Citizenfour helped to begin the conversation about government surveillance and privacy, which is especially relevant today in light of the ongoing FBI-Apple encryption dispute. Her exhibition is at once virtual reality, nightmare, warning, art installation, performance, and a personal meditation on sleepless nights. To chilling effect, she uses redacted material from her own FBI files, images of drones, videos of interrogation, her films shot in war zones, and the Government’s intrusion via surveillance into her daily life. Unbeknownst to me and other museum visitors was the fact that we were interactive players in an immersive media environment and that we ourselves were under surveillance as we moved through the exhibit.

Still. Laura Poitras, O’Say Can You See, 2001/2016. Two-channel digital video, color, sound. Courtesy of the artist.

The newly relocated Whitney Museum is near ground zero, the site of the World Trade Center bombings. The USA Patriot Act, enacted in 2001 and currently extended until 2019, stands for: “Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act.” The Patriot Act puts all U.S. citizens and non-citizens under surveillance all the time. The spirit of the Patriot Act flatly contradicts the 4th Amendment guaranteeing our right to privacy. Poitras left the U.S. for Berlin when, after constantly being detained at many airports, she believed she was on a government watch list. (The U.S. does not release the names of those on its list because of “security reasons”—two words constantly used to deflect any criticism of state surveillance) . She had already made one film in occupied Iraq, the Oscar-nominated My Country, My Country (2006), and another in the volatile Persian Gulf state of Yemen, The Oath (2010), and it was in Berlin that she finished Citizenfour, the Oscar-winning film about Edward Snowden. The Whitney show and a separate accompanying book called Astro Noise: A Survival Guide for Living Under Total Surveillance, are her first projects in the United States upon returning from Germany.

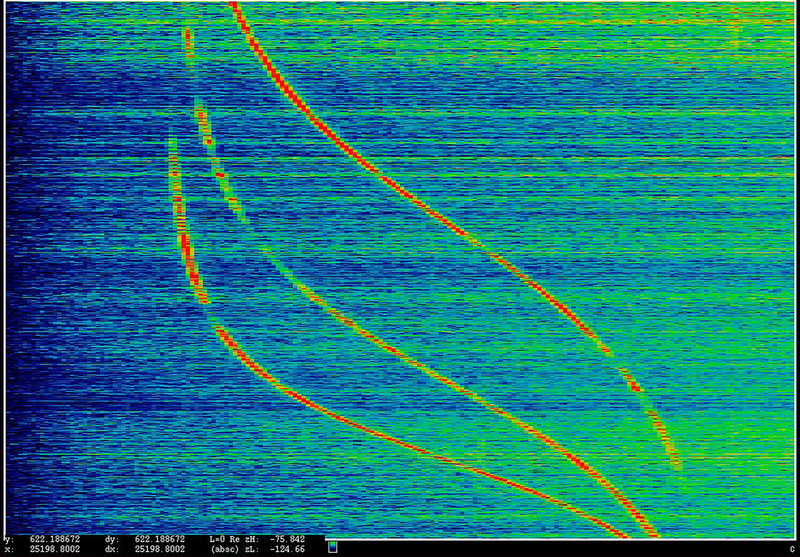

One enters the exhibit and encounters Anarchist (2016). At first glance, it appears as a visually uninteresting series of abstract inkjet prints, but it became more interesting once I learned that the prints are in fact drawn from descrambled images of surveillance ephemera: satellites, drones, and radar given to Poitras by Edward Snowden. The exhibition consists of four rooms. The first room has a two-sided video installation, O’ Say Can You See, on which one side presents slow-motion color imagery of shocked New Yorkers gazing at the aftermath of ground zero after the collapse of the Twin Towers, while on the other side are grainy black-and-white nightmare video footage of two prisoners being towered over by two American soldiers. One of the “detainees,” Salim Hamdan, the subject of Poitras’s The Oath, has a white bag over his head while his interrogator verbally threatens to hurt his family. We watch all of this to a sound track of a cut-up and slowed-down The Star-Spangled Banner.

Installation view of Laura Poitras: Astro Noise (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 5—May 1, 2016). Photograph by Ronald Amstutz

Then comes Bed Down Location. White noise and muffled talk lulls me toward a carpeted platform in the middle of the gallery; the comforting sounds make me want to lie down and gaze up at three different night skies of Pakistan, Yemen, and Somalia. (There is a discreet hole in the night canopy which reveals a surveillance camera that is recording me as I lie there). The beautiful menacing night skies, where danger is in plain sight, reminds me of the work of Trevor Paglen, the San Francisco artist whose own work focuses on U.S. black sites and surveillance. Paglen’s cinematography appeared in Citizenfour, and he is also a contributor to Astro Noise: A Survival Guide for Living Under Total Surveillance.

Next is Disposition Matrix, a series of 20 rectangular peepholes in an L-shaped room. The holes remind me of the slits in the stone walls of the medieval castle Krak des Chavaliers, located in present-day Syria, or the shape and “look” of redacted text. Peer into a hole and you espy an NSA data center under construction, images from Abu Ghraib, unreadable texts, and cartoon drawings of torture devices, fragments of an interview with NSA whistle blower William Binney, an Afghani water-boarded in Guantánamo, or a Yemeni wedding about to be destroyed by a drone attack. The glimpses intrigue as much as they frustrate. Both obfuscating and revealing, like a striptease, the experience of looking leaves me with a feeling of dissatisfaction, unable to put together any cogent story or picture from the material.

Installation view of Laura Poitras: Astro Noise (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 5—May 1, 2016). Photograph by Ronald Amstutz

Finally, I arrive in the last room, where I discover that I and everyone else in Astro Noise have been and are being monitored. First, there is the thermal imaging footage that was recorded by the concealed camera while we were lying down watching the night skies, projected as a video. The heat of the faces and hands read red and our clothes blue, and we see the afterimage of body heat clinging to the carpeted surface after we leave the room. (This is the same thermal technology I assume they use in current drone warfare.) And secondly, on another monitor, we see the device numbers of museum visitors collected by a “Wi-Fi sniffer,” a wireless device that can track the serial numbers of your personal mobile devices. In another corner of the room are Poitras’s personal FBI files that have been redacted and released by a Freedom of Information request. She discovered that she had been under FBI investigation since 2010 while filming My Country, My Country on the roof of a Baghdad apartment, which was near a clandestine U.S. military operation. In a short audio recording, she tells us that shooting this footage “changed my life, though I didn’t know it at the time.”

In a recent interview in The Village Voice, journalist Anita Abedian asked Poitras about her recent forays into art making and the connection to her journalism. Abedian suggests that it is a way to help Poitras’s audience become more reflective. Poitras admits she is intrigued with working with people in an interactive manner in the physical space of a museum, rather than working in long-form cinema. She hopes that it can be a new way for her to express herself and communicate about things she cares about.

For me, this material, stripped of the rigor and context of investigative journalism, descends into an exercise in intellectual play and museum entertainment. The exhibition space at the new Whitney Museum does not have the life-or-death charge of a war zone nor the intrigue of a secret spy location. I find myself agreeing with Mostafa Heddaya who, in a recent article on Astro Noise, points to the fact that the institutional framework itself is depoliticized, and supports a “hermetic liberalism well suited to the inert politics and personalism rewarded by the capitalist material art system.” He warns us to be wary of well-intentioned institutions. Art about surveillance art has been with us since the 1980s. Astro Noise’s mishmash of materials, evidence, and propositions, although packaged in a pleasing formal way, ultimately, is not enough. It makes me wonder about the role the Whitney Museum sees for itself as a cultural institution, using its clout to invite an artist with Laura Poitras’s reputation and accomplishments to surveil its audience in a well-intentioned show that ultimately misses its mark.

Installation view of Laura Poitras: Astro Noise (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, February 5—May 1, 2016). Photograph by Ronald Amstutz