Ghanaian artist Serge Attukwei Clottey is eager to galvanize positive social change, and focuses his performance, video and sculptural work on the crucial environmental and political issues that plague his local community. Hoping to alter the awareness and behavior of his audiences, he covers topics such as water conservation, plastic pollution, and exploitative commodity trading.

He is the founder of Afrogallonism, a movement that draws attention to the cultural effects of Ghana’s water crisis. Yellow plastic jerrycan (jugs used for storing water in Ghana, also referred to as gallons) are a frequent material in his work. Drawing from Ghanaian history and traditional art, Clottey creates costumes, masks, and sculptures that combine plastics and electronic gadgets with bones, shells, and locally sourced textiles.

As a current resident at the ANO Cultural Research Platform in Accra, Clottey is developing a large installation called River Goddess built of stitched plastics that will cover the dried up Kpeshie Lagoon, in an attempt to draw attention to pollution in the region, and rekindle relationships with the sea gods of the Ga people. Through his engagement with local communities and use of social media, he is seeking ways to spread his message and broaden its reach to international audiences.

The art scene in Ghana has been very active in the last few years. What’s happening at the moment?

Ghana is an African art center in general, and the last few years have been very productive. The art scene has become really vibrant with emerging artists who are breaking away from traditional art and working more with contemporary art. For example, Ibrahim Mahama was one of the young artists represented at the Venice Biennale this year. His participation put Ghana on the global map and had a lot of impact on young artists as well. There are a lot of new projects that have followed, and more artists are engaging with the international art scene now.

Where is the activity focused? Is that happening in galleries, museums, or project spaces?

The activity is mostly developing in public spaces because there are just a few galleries here, and they only show a particular kind of work. The galleries are into traditional arts, so we need public spaces. There are a few institutional art spaces that we also exhibit with, like ANO, which is run by Nana Oforiatta Ayim, and others we do workshops at.

Your own work focuses on local political and environmental issues. What’s your perspective on how artists should relate to the background that they come from? Do you feel like it’s the responsibility of an artist to make change or make society better?

I think artists have a role to play in society. Through performance art, I create awareness and point out political issues in my country. A lot of people are afraid to speak out against the political system, but there are many other artists working in different parts of Africa using the arts to criticize politics.

Social Sculpture, 2015. Performance documentation. Malibu, California. Photograph by Stefan Simchowitz. Courtesy of the artist.

Social Sculpture, 2015. Performance documentation. Malibu, California. Photograph by Stefan Simchowitz. Courtesy of the artist.

In your recent solo exhibition, The Displaced at Feuer/Mesler in New York, you use video, sculpture, and installation, but performance is your main priority. Why choose performance?

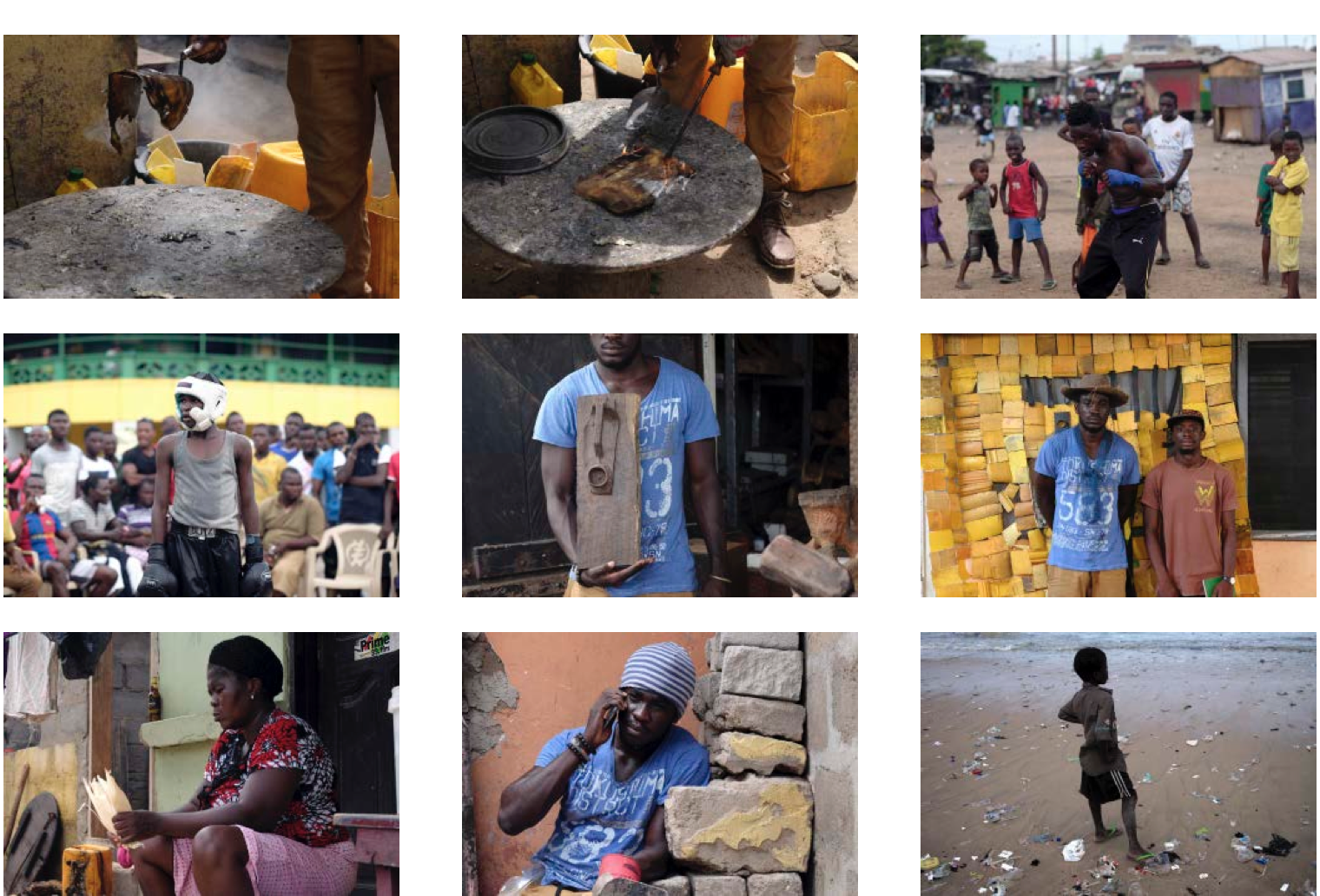

Performance was my first encounter as an artist. When I was growing up, all I dreamt about was movement. When I studied in Brazil, I saw a lot of street performers and street art and I realized why I’ve been dreaming so much about movement. Performance was the easiest and most powerful way for me to express myself as an artist. At the time, I worked as a model for an agency in Ghana doing fashion shoots. I realized that I looked like a puppet in that situation. They told me how to pose, how to walk, and all that. Taking that experience from the fashion industry, I decided to incorporate it in my art because I know that my body is part of my process. I use myself in my work, and I use myself as an object. I always find ways to share the process of my work publicly. I use the process of collecting my materials as part of the performance because it’s a dialogue within the space I’m in. When I go to the dump to collect my materials with others in my performance group GoLokal, we mostly wear women’s costumes because women struggle with these materials in daily life. In Ghana, the women are responsible for taking care of the homes, the cooking, and all of that. We wear women’s clothes on the street to go pick up the water gallons and sometimes we carry fifty of them on our backs. People see it and start to speak about it. They ask why we always carry the gallons and what we use them for. Gender and sexuality are key elements in our performance. The process becomes a performance with the public. It creates a wider audience, which also is how I explore the concepts and ideas in public spaces—by interacting with people.

The Displaced, 2015, Performance documentation. Labadi , Accra, Ghana. Production still by Charles Whitcher. Courtesy of the artist.

Are the members of GoLokal also artists? What are their backgrounds?

Some of my performers are not artists. One is a photographer. Actually, I’m teaching him how to use a camera so that we can have one person who photographs our performances. Most of them work in other fields like electronics, IT, and tailoring. There are even soccer players who want to be part of the group because they are excited about what we are doing.

We also do a lot of costuming, which was influenced by trade on the African coast. We live in a city where we have ports and a long history of trade. It’s a place where European costumes and African costumes together. It is just part of how we live. With my group, we focus a lot of attention on costume. Fashion is a part of it, but it also deals with the whole history of our time. For example, we don’t have winter here, but we still have winter clothes in the markets, so people just wear them because they are coming from Europe. People don’t dress according to the weather, but because of the colonial influences.

A lot of the pieces you create are very craft based. You’re collecting materials from the sea, the dumpster, or the streets, and you’re anthropomorphizing them. A lot of the materials or objects, like the jerrycan, become human masks, which reference traditional Ghanaian masks. What is your relationship to the tribalism and the ritualistic practices you incorporate into in your work?

My ancestors were traders with other towns; they were warriors and they had a spiritual side, which was used for fighting. I looked into that spiritual aspect; they had a costume they only used for fighting wars. I’m interested in how history and tradition can be used in our time. For me, it’s also about telling that history to my generation. What kind of connection can I make between that time and our time? Their stories were not documented, they were just being told from generation to generation. So I put all those stories into the performances I make using costumes and masks. The masks are something that will survive since they are made of plastic.

How did you first start working with issues related to climate change, and how did you decide to focus all of your work and energy on it?

When I completed art school in Ghana, I was still making traditional figurative painting and working with my dad, who is also a painter. Then I received an opportunity to study in Brazil, where I realized that there are more issues to deal with in art. I was working with foreign objects and materials, and I realized that there are a lot of materials in Ghana that I can work with. When I came back to Ghana in 2006, after finishing art school in Brazil, I decided to look into the issues that are relevant to the country. I wanted to look at waste management, and then I began looking at climate change, which is how I first got interested in working with the plastic gallon jugs and developed the concept of Afrogallonism. I’m developing it as a concept and a movement that can be explored globally as a means of changing trash into treasure. It’s about the future of globalization and identity.

Perfectly Adapted, 2016. Plastic, wire, and oil paints. 64 X 88 inches. Photograph by Nii Odzenma. Courtesy of the artist.

Aesthetically, many works of yours such as the Plastic Journey series, for example, draw similarities to the work of well-known Ghanaian artist El Anatsui. Anatsui uses pressed bottle caps bound with copper wire to create sculptural wall works, whereas you’re using plastic and copper wire. What is your relationship to his work?

I first learned about his work in 2010, but even before that, I was trying to find ways to get rid of plastics. I wanted to make paintings without paint. Plastic has a very long life span and we don’t know how to get rid of it, so I began cutting it up and layering it, at first in a figurative way, and then as abstract works. My work talks about migration and material value. Copper is one of the most valuable commodities in the markets in Ghana, so combining plastic and copper creates an equal balance in the artwork. Anatsui’s work references handwoven Kente, which is a traditional fabric, but mine represents a migration of objects and how we consume so much plastic in our daily lives.

Can you explain the history of the water shortage crisis and why the gallon jugs are so significant to you and your community? I understand they are also called Kufuor gallons.

Between 2002 and 2005 there was a serious water shortage. Sometimes the water would run only once a week. As children we carried these plastic gallons for kilometers to collect water. The name Kufuor gallons came up because water was scarce during the time of John Kufuor’s presidency. It was mostly women who were using the Kufuor gallons because they were the ones who woke up early to carry these water gallons for ten kilometers to take care of the house. At one time you would see hundreds of gallons in the queue. On the gallons, people would mark their names and write in different colors. Looking at the queue, you could tell the language and language barriers. It creates a story about people and about religion. You see the gallon and you know whom it belongs to. A color may be used like a red splash, which represent danger, or blue, which represents happiness. Sometimes there are just names. When it’s names, it tells you which tribe the person is from, or which religion. You might see a Christian name or an Islamic name on the gallon, for example. It is also political statement. Within the queue for water, you can tell the whole story of where these people are coming from. The water shortage created a very vibrant, colorful community. It’s something I photographed and also inspires my collages. It’s arranged according to the architecture and it’s all over the streets. Every house has about 100 gallons. Because of the water shortage, we’re still using them. People even sleep on them. People use them as chairs. They use them as beds. The gallons are used for different purposes in their homes, which makes it part of us.

Your work often deals with local political issues in Ghana and your own local experience with migration. What was your experience like working in Vienna on issues of global migration?

That was my second trip to Europe. I was in residency for three months at the Kunsthalle Exnergasse. I didn’t know anybody in Austria, and I had three months to come up with a body of work. I decided to reach out to other Africans in the diaspora. I told them about my interest in collaborating and asked, “What are the issues I can work on?” They gave me the idea of migration. I was already working with migration, but I wanted to interview them about their experience as Africans living in Austria. I ended up collaborating with a number of people including a poet, an artist, a dancer, and a performing artist. I was coming as an African and as an outsider, asking them to share their experience through the arts. Collaborating with them gave me a better understanding of their experience as Africans living in Austria. Within the exhibition, I asked them to give me a message written on tobacco envelopes that I could take back to Ghana and share. I feel like a messenger to Africa, sending stories to Africa, and sharing the messages of people in the diaspora with the continent. When I came back to Africa, I did a performance with those messages. I put the messages in a piece of luggage, went out on the street, and dropped it so the messages just fell out. Then I asked people to read and respond to those messages. Afterwards, when I came back to Austria again, I was able to deliver the messages people shared.

Your project Gold Coast critiques the growing Chinese mining industry in Ghana. What’s happening between the Chinese communities and the Ghanaian communities?

Chinese corporations are now taking over the illegal mining companies and are hiring locals, including kids, to do the mining. They are invading the local communities. I think it has to do with the government. It’s affecting the country because children are losing their lives. They are tearing families apart. Chinese contractors initially came to build our roads and transportation systems. That’s how they discovered the illegal mines, by constructing roads from the villages to the countryside. I think they are working with local chiefs because that’s the only way they could get access to the mining sites. They invest so much in the production. They bring guns and other heavy ammunition to guard the mining sites they operate, ward off the locals from checking their operations, and use explosives and other poisonous substances in their mining activities. In the end, these poisonous substances are causing environmental and health hazards to the locals. They are also fishing on our coasts with all sorts of chemicals and equipment, using lights to fish and a lot of machines too. The local people who traditionally use manpower to fish are struggling to make a living from fishing. It’s affecting the environment and also the people in the country.

What did you do for Gold Coast?

The performance was about gold mining. Since the coast was called the Gold Coast before, and it was only called Ghana after 1957, I was curious if there was still gold on the coast. Together with my group, we built all the equipment that was used locally for gold mining. The ocean is just behind one of the biggest art galleries in Ghana called Artists Alliance Gallery. So, we went there and we brought all the local equipment for gold mining. Together with kids, who represented child laborers, we worked for five hours. Automatically, the kids got tired and they started sleeping on the rocks. These filmmakers from Sweden were going around Africa to document artists’ work, and I was one of their selected artists so they filmed the whole process. For five hours, we were mining gold and a lot of people from the community came out to see the performance. Everyone was curious and suspicious. Rumors were spread all over town. The message even got to the chief of my town and the chief was very upset because they thought we were actually mining gold. People came looking for me and I had to face the traditional court and all that. That performance was very powerful. People immediately reflected on how mining effects the environment because we were digging the sand into the ocean, and the whole place was polluted. An action like this creates a very strong statement on how the illegal mining is affecting the environment and the economy.

How do you promote your work locally? Do you post on certain blogs? Or do you use social media?

I use Facebook. I sometimes create Facebook events and upload images. Sometimes we just go to perform without an announcement. It depends on the idea of what we’re doing. I use a lot of social media to promote my work. I have friends who are photographers, writers, or bloggers. I invite them, and then they put up a review of the performance and share it on their blog. I also have a blog where I post updates of my performances with a brief text about the performance. I use social media to reach international and local audiences.

I’m curious about the scene in Ghana. Are there other artists you’d suggest looking into? Or other people you think are important right now?

I have a few peers I look up to, who are doing very well. Ibrahim Mahama is one of them. There is another performing artist called Bernard Akoi-Jackson. We have quite a vibrant group of artists who have been very productive over the past four or five years. We always look into each other’s work and advise each other. We are engaging in conversations and exploring concepts and ideas together. There are a few people like the reknowned journalist Anas Aremeyaw Anas, who is undercover right now. Anas has been documenting illegal issues in the country. He’s inspired me a lot because of the major role he plays in society. I also have friends who are art historians and architects who inspire my way of thinking, like my friend the art writer, filmmaker and curator Nana Oforiatta-Ayim, who inspired my ideas for building plastic houses.

When you’re performing in public space, do you ever feel the threat of being arrested or of violence against you or the performers?

Yeah, sometimes I feel threatened when I’m performing because performance art is quite new in Ghana. I think because it’s so new, sometimes people don’t understand what we do. Many of our performances are very political, and so, when people come around to watch us, sometimes they say things that make us feel threatened. My group and I are beginning to understand the art better ourselves. In that process, the fear disappears. We have also adopted ways of involving audiences who come to see us perform. I also think that when we feel threatened, it means people are getting the message.

It’s something that I’m doing, not only for myself, but also for the sake of the people. There are a lot of things that people want to say, but don’t feel comfortable speaking out about. If the government is corrupt, it affects every living being in the country. I’m working on a performance for this year’s election. It’s called The Museum of Tolerance. I am looking into how we can address political issues through the performing arts. I am collaborating with writers, filmmakers, and photographers. Also, because I am an artist, and I have this social media strategy for communicating, I am able to speak more freely.

During your travels abroad, were there experiences that affected you negatively?

When I went to the US, I met a lot of artists who were not very curious about what I do. When I was introduced to them, they didn’t talk much. When I’m in Ghana and I talk with an artist, they are very curious about what I do, and try to know what I do, and I show them my work. In the US, people that I met were very distanced. They were holding back, and I found it very uncomfortable. Also, in Europe, that’s where I really felt my color. In Ghana, we don’t talk about color. We don’t care. When I went to Austria for the first time, I actually started looking at myself because people were treating me very differently. Any time I went to the shop, I felt like people wouldn’t speak to me. Or, when I got lost, people wouldn’t help me with directions. I felt very bad at that moment, but I said to myself, well, I’m not from here, so I need to focus on why I’m here. It doesn’t matter what color I am. But with all those things, it’s a learning process and it’s about how people understand what they are doing.