Mark Baum: Elements of the Spirit

Krowswork

480 23rd St., Oakland CA 94612

January 30-March 6, 2016

They say that artists transcend class. That they glide effortlessly from the studio to the showroom to the boardroom. But that’s for the lucky few. The vast majority of budding artists are forced through family concerns and financial matters, only to leave the field entirely. Those remaining usually fall through the cracks, forsaken by the art world at which they lie at the very core. There are no archivists, historians, biographers, curators, vendors or venues of culture without the artist, and yet the artisan is very often the least rewarded of them all.

A painter friend of mine recently passed away. Andrew Pettit was an Army brat born in Japan, later serving in Korea. He had families and lost them. He resided in Chinatown, San Francisco, subsisting hand-to-mouth. His prolific painting habit precluded substantial outside employment. Mutual friends supported him, buying up bodies of his work in desperate hours of need, which despite drawings and paintings of a detailed nature, were surprisingly prolific. My acquaintances did this because they respected Andrew’s passion and possessed the kindness and resources to help a friend in need. Service in the military proved his eventual safety net, landing him at the Yountville Veterans Home of California, where he was provided a painting studio and worked until his final days, earlier this year.

Surprisingly, it was the military, dismissed and disdained by a majority of artists, which provided comfort and subsistence at the end of his days. Not the galleries, who never exhibited him. Not the universities, who never invited him to speak. Not the scholars, who found no papers to examine. Not the writers, who couldn’t find a hook to lay their story upon. Not the museum professionals, on whom he registered not a blip on the screening process.

The working artist—who has ventured forth uninterrupted despite depravation, dependent upon a few caring friends in a position to assist, and whatever social safety net is available—does have a glimmer of hope. Their salvation is the very thing that was denied in life. Paintings once unappreciated, may perhaps gain patina in perspective.

Mark Baum, Summer Morning Arising (detail), 1964. Oil on Canvas. Photo credit: John Held, Jr.

On the other hand, Mark Baum, currently being exhibited at Krowswork, did have some small measure of recognition during his lifetime. Born in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in 1903, he came to the United States in the 1920s, exhibiting at the Whitney Studio galleries at the end of the decade. Alfred Stieglitz collected him. LIFE Magazine acknowledged him in an article about artists’ jobs, in their January 25, 1954 edition: “Fifty-one-year old Mark Baum has always kept two jobs going – his painting and one other job to let him paint. Currently he is painting, since his ‘other job,’ cutting Persian lamb skins [pictured above] is a seasonal one…Working, he claims, has kept his painting…more realistic than abstract.”

It was his realistic painting that brought him notice. But he was dismayed by the appellation “naïve” and “primitive,” which accompanied this attention. Baum’s early works branded him a later day Henri Rousseau, the French painter also known as Le Douanier (a playful pun on his occupation as a toll collector), and were not without a modicum of success—the Metropolitan Museum buying a small selection of his these representational works later in his life.

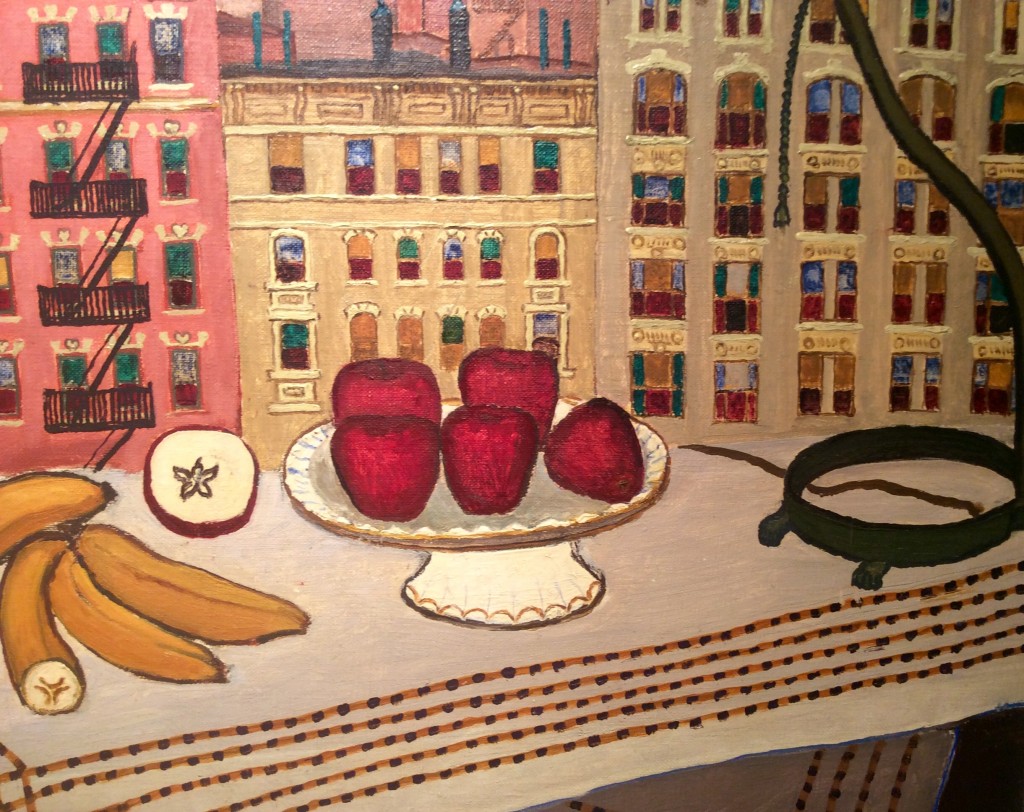

Mark Baum, Still Life with Lamp and Fruit (detail), 1946. Oil on canvas. Photo credit: John Held, Jr.

But it was not an easy life. Fur cutting was a seasonal affair, and the Depression devastated the trade, although he worked at the profession until 1955. He found some measure of support in the WPA project, but on the whole, he was supported by his wife who was a successful educator, and towards the end of his life, by his two sons, both of whom attended Harvard.

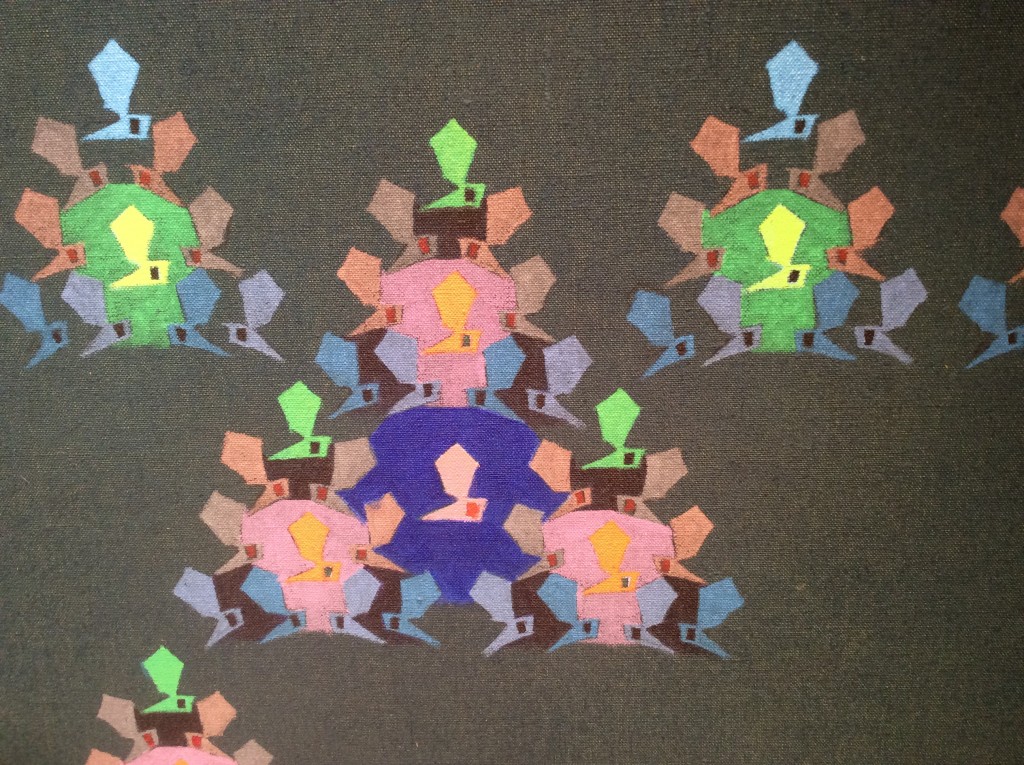

The same year that he quit the fur trade he was included in an international traveling exhibition, “American Primitive Paintings,” sponsored by the United States Information Service, and that may have been the final straw. Soon after, he began working in an abstract style, leaving representational painting behind. His earliest abstractions featured staircases, which he further reduced to what he called, “The Element,” a non-objective symbol varying little over the next 40 years, which he placed in various compositional configurations.

Mark Baum, Levels, 1956. Oil on canvas. Photo credit: John Held, Jr.

The ironic thing is, he never overcame his “primitive” approach to painting, even by his embrace of abstraction. Like his representational work, his ‘Elements” are flat, placed upon a monochromatic background, with little mixture of pigment. Abstraction in the 1950s pushed the boundaries of “painterly.” Baum’s work is anything but. Flat solid colors mark his paint application during this period, continuing the humble range of his earlier representational work. In the end, it was all about color, composition, and mindless repetition of a single image.

You can see how this approach brought him a measure of comfort. After a period of transition, abstracted works (predominantly staircases) became purely non-objective. The configured “elements,” came to resemble circuit boards, which he began to collect, sensing the similarity. The “mindless repetition” mentioned previously, is not derogatory or disparaging. Rather, it describes a self-conscious attempt at a meditative state. I believe this is what sustained him. Painting can be used as a tool to affect an altered state. He painted all of his life, and that itself is a feat worthy of praise. Over a lifetime, persistent artists reap their own reward, reputation be damned. Baum could have desired greater recognition upon his death in 1997, but he never lacked the passion to proceed, courageously outpacing those abandoning the field due to neglect.

Mark Baum, Adventure (detail), 1968. Oil on canvas. Photo credit: John Held, Jr.

After years of silence, stored paintings gathering dust find their voice. Reputations rise and fall. Twenty years after his death, Baum’s circuit board compositions reveal a prescient perspective on our digital age. This is not the first time Krowswork has taken on a deceased painter’s estate, reviving a dormant career. It reflects a major responsibility of the gallery system—not only to confront the contemporary but also to rectify the negligence of the past.

Installation view, Mark Baum at Krowswork, Oakland, CA, January 30-March 6, 2016. Photo credit: John Held, Jr.