Hank Willis Thomas: Evidence of Things Not Seen

Kadist Art Foundation

3295 20th Street, San Francisco, CA 94110

February 24, 2016 – April 9, 2016

Evidence of Things Not Seen, a multimedia exhibition of work by Hank Willis Thomas, functions as a proscenium theater on race, revealing how we are all actors in an ongoing, everlasting scene of violence, visibility, and voice. In both the exhibition’s title and a 5-channel video work, Thomas’s muse is African American author James Baldwin, a man who did not perform a “blackness” that was familiar to white America in the 1950s and beyond, but rather offered a voice so elevated by intelligence and observation that it buoyed and fractured the low-laying, singularly positioned questions of his interviewers. Baldwin speaks from an experience so other—an openly gay black man in the 1950s—that he accurately reflects the prismatic nature of human relations, particularly the hall of mirrors which structures race relations.

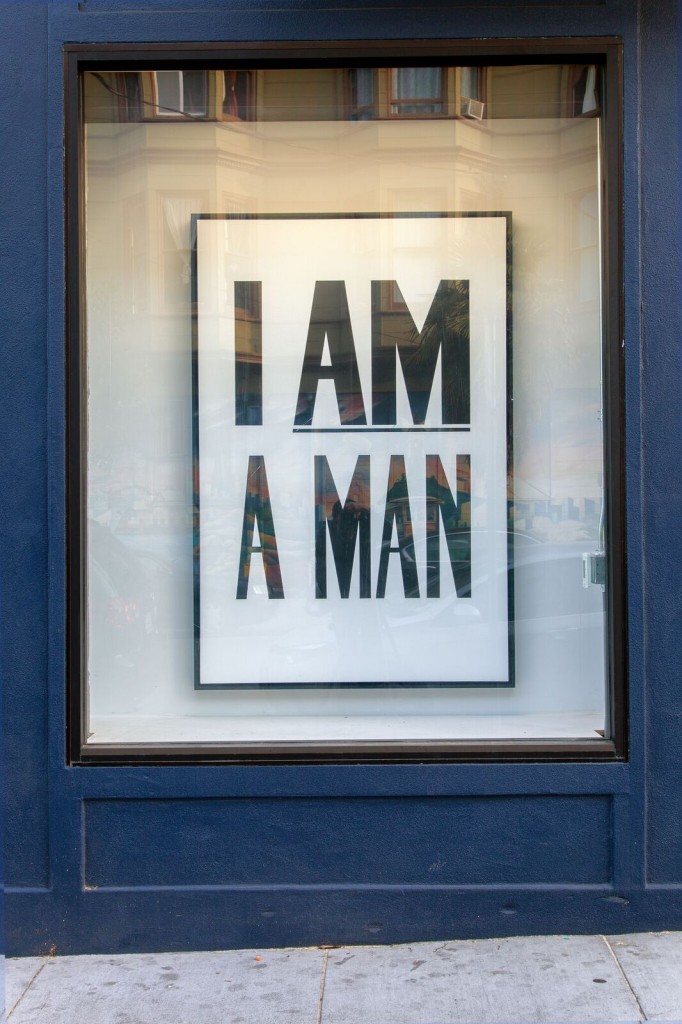

Hank Willis Thomas. I am a Man, 2013. Liquitex on canvas, 72 x 48 inches. Photo by Jeff Warrin. Courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

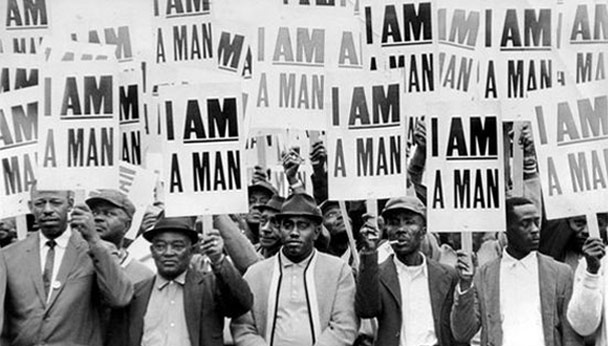

In the windows of Kadist, two pieces hang together. On the left is Caesar’s Visa (2009), a neon sign which uses the language from Visa ads meant to seduce people into systems of finance and capital, otherwise understood as the late 20th century’s form of indentured labor. On the right hangs a large painting with the words “I AM A MAN,” modeled on the placards worn by striking sanitation workers in Memphis in 1968, which recognized their basic humanity in a society that historically and consistently denied it at every level.

Both pieces have an underlying connection to capitalism and its impact on our perceptions of ourselves and of others. While advertising language is meant to be aspirational, conferring special status onto the consumer, I am a Man (2013) pushes the arc toward not asking for rights or special status but to enter into the category of human, which had been explicitly denied to slaves. Today, “I AM A MAN” reads as an antecedent for “#BlackLivesMatter” as both are concerned with asserting that black lives are human lives. This affirmative statement, “I AM A MAN,” starts off the call and response between forced invisibility in our racist society and the proclamation of experience, which is echoed throughout the exhibition, particularly through Baldwin’s voice.

Hank Willis Thomas, Black Righteous Space: South African Edition, 2014. DVD (playlist and video installation), Microphone, and mac mini, approx. 60 mins. looped. Photo by Jeff Warrin. Courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

Black Righteous Space: South African Edition (2014), is a stage for such call and response. The piece consists of a platform with a microphone and a screen behind it. On the screen, a symbol for the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, a South African Neo-Nazi party, is flashed in the colors of South African National Flag. The image keeps its structure and form until someone steps onto the stage and begins to speak. The louder the voice, the more the symbol breaks apart, fracturing into smaller and smaller bits and pieces, forming new patterns. It’s a simple but powerful metaphor on how individual and collective voices are necessary to break up power systems. People take the stage, use their voice and create change. The soundtrack for the work, a 60-minute loop played continuously in the gallery, features music, speeches, and voices which had been silenced during apartheid. Black Righteous Space has two other editions: Germany and the United States, which also feature symbols of oppression coupled with the colors of their liberation. In the United States edition, the flag is confederate while using the colors of the Black Panther Party.

In this piece and throughout the exhibit, it is clear that Thomas sees agency and visibility as part of an ever-changing matrix of being, which is why Baldwin is the key actor. Anyone who takes the stage will be speaking from a moment of spontaneity, unknown origins, and personal performance. Thomas creates a platform to underscore that the multiplicities of the individual voice have the power to break apart formerly monolithic structures. These works warn that when identities become fixed and known, stereotyped, oppression is near.

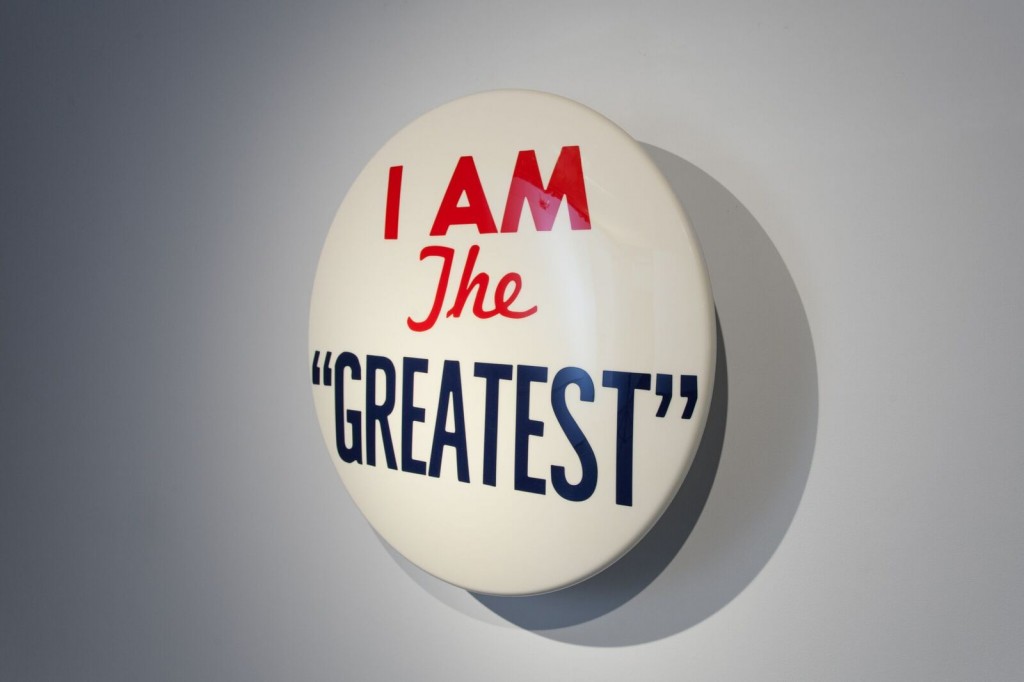

Hank Willis Thomas, I am the Greatest, 2012. Mixed media, 331/2 inches in diameter. Photo by Jeff Warrin. Courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

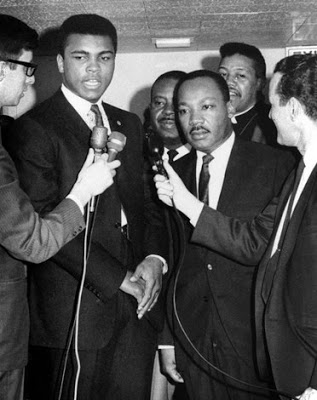

Across from Black Righteous Space is an oversized button, which reads, “I am the Greatest,” recalling Muhammad Ali’s famous grandstanding. In this context, it is a powerful claim of worth and self-worth, of black identity that is not only human but also better than anything else. One can imagine Ali taking the stage of Black Righteous Space, as he did in 1967 when he resisted the draft and went to jail, saying, “”My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father… Shoot them for what? …How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Muhammad Ali, the former Cassius Clay, was convicted by a U.S. federal court in Houston on June 20, 1967. Above, he is shown when refusing induction at the Houston draft board, April 28, 1967. At his right is the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Sitting down on the platform bleachers to watch A person is more important than anything else (2014), a 5-channel video piece, is akin to going to a play. You hear voices from backstage and offstage as people walk in and out of the frame; dialogue overlaps, and different characters emerge and recede. This piece effectively employs the form of a multi-channel video to highlight not only James Baldwin’s charisma and insight but also to show him in an ongoing dialogue with white audiences and interviewers from the 1960s to the mid-1980s. Excerpts of Baldwin’s historical interviews are interwoven with footage taken from televisions documentaries, the news, and Angela Davis’s reading of Baldwin’s writing. His statements on homosexuality, the first black president, the economy, materialism, capitalism, and racial profiling are juxtaposed against contemporary footage of these same topics showing the historical continuity from one moment to the next. In the first few minutes of the video, we hear a voice ask “James Baldwin, who are you?” On another screen, from another time, Baldwin responds, “I am speaking as an American citizen, I’m speaking also as the grandson of a slave…Someone who represents a very complex country which insists on being simple minded.” In his response, Baldwin sets up the lop-sided interface between his interviewers and his experience.

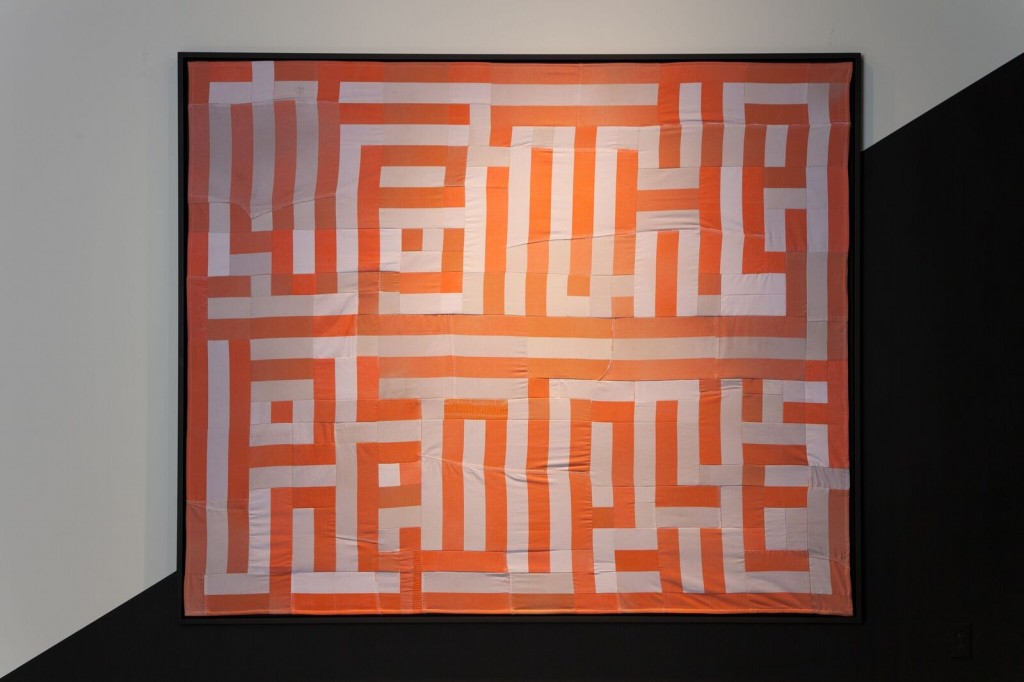

In the center room, featuring Black Hands, White Cotton (2014), Two Little Prisoners (2014), and We the People (2015), Thomas underscores the historical thread between slavery and our economic system, where black men have a higher rate of incarceration, experience a wage gap with white men and have historically higher levels of under and unemployment. The chains of slavery and sharecropping have become the chains of the prison industrial complex, criminalizing black men at younger and younger ages to the point where the phrase “school to prison pipeline” is part of popular vernacular.

Thomas’s quilt work We the People is constructed out of decommissioned prison uniforms while Two Little Prisoners shows two young black boys with a police officer. The images are on a mirror, putting the viewer’s own body and identity in dialogue with the images they are seeing. Although the photograph employed in Two Little Prisoners was taken from LIFE Magazine and was most likely a strange staged joke, it, like all jokes, contain some truth.

Hank Willis Thomas, We The People, 2015. Quilt made out of decommissioned prison uniforms, 73 1/4 x 88 1/4 inches. Photo by Jeff Warrin. Courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation

Invisibility and visibility is a complex matrix when it comes to race in the US. The white imagination is filled with stereotypes and myths about black people from the savage to the welfare mother to the mammy to the thug to the Uncle Tom, and black bodies have been under constant surveillance since slavery. This type of false visibility (possibly akin to Marx’s notion of false consciousness) is really the marker of invisibility that Baldwin articulates when he says in A person is more important than anything else, “We have invented the nigger. I didn’t invent him. White people invented him. … What you were describing was not me. What you were afraid of was not me. …You still think, I gather, that the nigger is necessary. Well, he’s unnecessary to me. … So I give you, your problem back. You’re the nigger, baby; it isn’t me. ” Baldwin is telling the audience that when they see him, they are seeing the problem that they imagined, that they created. He is unknowable until he speaks. He is unknowable by the audience because their knowledge is produced by a system that consciously obstructs the Baldwin’s humanity.

In this exchange, Baldwin gives us an epistemological framework to understand the how racism defines him. As the title and Baldwin suggest, there is always evidence. It is simply a question of whether or not it we can comprehend it, if we have the intellectual capacity to correctly identify who stands before us.

In his work, Intentionally Left Blanc, Thomas wryly interprets this problem by using retro-reflective paper. When you first look at the print, it is predominately white but with light shining on it, from certain angles, a crowd can be seen. Whiteness blinds and only a certain type of light makes the black crowd in the image visible. Visitors are encouraged to use a flash so they can perceive the crowd in detail, which is akin to flash moments in history where black lives become suddenly visible and then become masked by whiteness again once the light is removed.

Hank Willis Thomas, A Person is More Important than Anything Else, 2014. Five channel video. Duration: 28.5 minutes. Director: Hank Willis Thomas. Producers: Natasha L. Logan, Karen Thorsen. Post Production Producer: Will Sylvester. Editors: Matthew Cohn, Rosa White, Noah Krell. Excerpts from the film The Price of the Ticket appear courtesy of the filmmaker. Photo by Jeff Warrin. Courtesy of the artist and Kadist Art Foundation.

Visibility in Baldwin’s (and Thomas’s) terms comes from puncturing this false visibility, creating holes to reveal the individual behind the stereotype. When an interviewer asks Baldwin, “Now when you were starting out as a writer, you were black, impoverished, homosexual, you must have said to yourself ‘Gee, how disadvantaged can I get?’” and Baldwin replies, “No, I thought I hit the jackpot.” He completely undermines the interviewers expectations, flaunting his fully embraced otherness. In fact he follows his statement with, ‘It was so outrageous, you could not go any further. You know. So you had to find a way to use it.” Otherness in Baldwin’s hands is an advantage, which confronts and degrades dominant ideologies, the status quo, and historic power relations. Baldwin is bold, he is courageous, and he does not hide. Instead, he expresses a deep self-love despite the expectation of self-loathing implied by the interviewer’s question. Later in the piece Baldwin says, “I don’t want to become white” contradicting the racist premise of whiteness as both aspirational and superior.

In the context of the exhibition, where the ongoing suppression and upheaval of racial conflict is played across time and space, it is clear that you need a theater to bring the recurring patterns of violence and resistance into focus to see a system that has been occasionally broken up but never completely destroyed. It reminds me of psychoanalysis, where after seeing your analyst five days a week for five years you slowly realize that you’re acting out and habitually re-creating a series of repetitive dramas; you see your self as an actor in a play which you constructed. Psychoanalysis focuses on bringing your unconscious into consciousness, to bring the messy, unseen, attractions, repulsions, guilt, and unacceptable desires into life in order change your actions and reactions.

At one point in A person is more important than anything else, Baldwin, speaking to an audience says, “Ask me the most difficult questions that you can. And I will not be able to answer them. But my responsibility is to hear them. And when you ask your question, any question, you begin to know more about what you really think.” This is remarkably similar to the therapeutic model of self-discovery. And played across a broad cultural context, it works well to expose the beliefs of Baldwin’s white audience. After this statement comes a series of questions from white people ranging from the role of the Negro in literature to their sense of shame.

Black Live Matter Sign, courtesy of the Internet.

In an artist video, Thomas has said that artists “work in our society’s subconscious”. The United States has been involved in the same repetitive behavior for centuries, unable to reconcile its past with its present, unable to take responsibility for slavery and its impact on every generation from the inception of the nation to this moment where African Americans still have to say “Black Lives Matter.”

Evidence of Things Not Seen is timely, inviting viewers not only to activate their voices but also to hear their voices in dialogue with all the others ones in the room. The room is an echo chamber and a chorus, with James Baldwin leading the call and response. It is a pleasure listening to Baldwin, reflecting on his deep connection to both his own humanity and the society to which he was born. The Evidence of Things Not Seen is about modes of visibility and invisibility, and it’s equally about things said and heard. At the end of A person is more important than anything else Baldwin finally answers the question, “Who are you, now?” with a strangely prescient response, “Who indeed? …I want to be an honest man and I want to be a good writer. And I don’t know if one ever gets to be what one wants to be. You know. You just have to play it by ear and pray for rain.”

A film program at the Roxie and Kadist runs concurrently with the exhibition. Please visit the site for more details.

http://www.kadist.org