MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture

Vancouver Art Gallery

750 Hornby St.,Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada V6Z 2H7

February 20 – June 12, 2016

There is an oft-repeated Fernand Léger anecdote that places him with Marcel Duchamp and Constantin Brancusi at a Paris aviation exhibition in 1912. While looking at a propellor, Duchamp turns to Brancusi and says something like, “Painting’s washed up. Who’ll do anything better than that propeller? Tell me, can you do that?” No one knows when Léger first told this story, nor to whom, nor what Duchamp’s exact words were, nor what Duchamp might have meant by warning a sculptor about the future of painting.[1]

Like all origin stories, this myth of modernism gains embellishments through the years, moving back and forth through time as we apply it to our reading of art since that moment: the discourse of modern art. Whatever the story’s veracity, Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1913) is often read as his response to his own questions. And with that work, in a room near the elevator on the fourth floor, the Vancouver Art Gallery’s current exhibition, MashUp, begins its telling of modern art history.

Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, 1913 (6th version 1964). Bicycle fork with wheel mounted on painted wooden stool, 126 x 64 x 31.5 cm, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased 1971

Commanding the gallery’s whole 35,000 square feet, MashUp attempts a chronological survey of modern and contemporary art, from Duchamp on the top floor through to contemporary artists like Hito Steyerl on the main. The task of this curation is made all the more daunting by the inclusion of film, architecture, industrial design, fashion, and popular music. However, the focus of the exhibition is narrowed down to the recombination of old elements into new forms, which reads as the essence of collage, assemblage, homage, readymades, sampling, mass production, appropriation, street art and, arguably, plagiarism.

Any exhibition that attempts to be so comprehensive, spanning a little more than a century and featuring the work of 30 curators and over 160 artists, is bound to have gaps in the version of history it chooses to relate. In this way, the impossible ambition of the exhibition becomes a strength by foregrounding its secondary intention: MashUp also functions as a sales pitch. It makes the case in ten-foot bold Helvetica letters, that the Vancouver Art Gallery needs more space: a modernized vault for its growing collection, more room to exhibit said collection, a capacity for ambitious curatorial projects gathered from collections around the world, educational facilities, performance spaces, a bigger library, etc. In short, MashUp explicitly lobbies for the completion of the west coast modernist pile of cubes recently unveiled by Herzog and de Meuron as the proposed future home of the VAG, and this reviewer is sold.

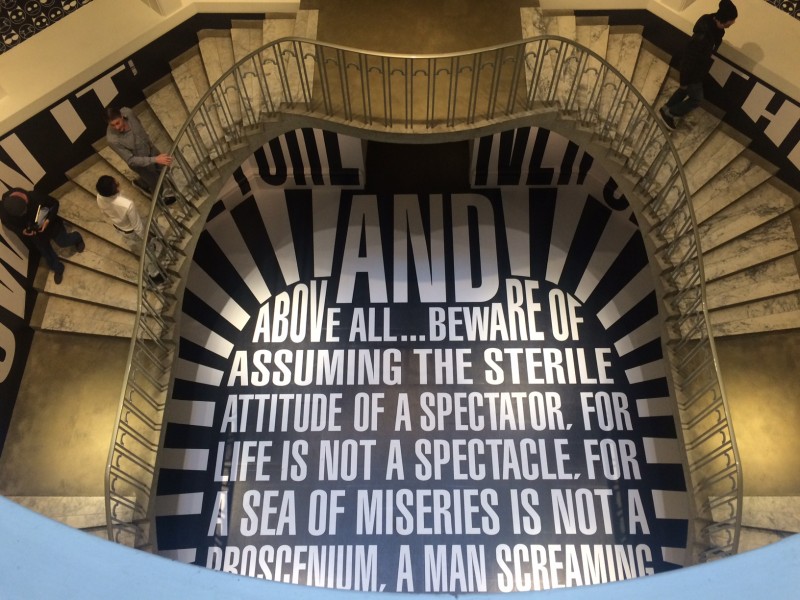

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Smashup), site-specific installation in MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture, exhibit at the Vancouver Art Gallery, February 20 to June 12, 2016, photo by Aya Garcia, courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery

This problem of space is directly tied up with the goal of curating modern and contemporary art. As the anonymous contemporary critic who writes under the name Walter Benjamin explains:

“The first obvious question regarding this concept is its practical sustainability, considering how much space we’ll need at ‘the end’ for such museums, assuming their continual growth, and how much time we’ll need to walk through them to see the exhibits… If museums are changing all the time, then the past is changing all the time as well.”[2] [3]

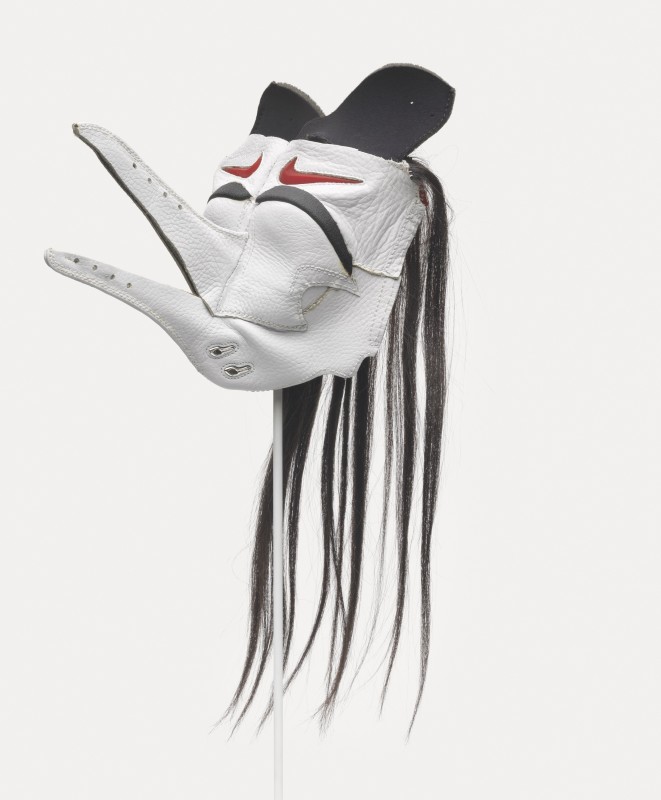

Brian Jungen, Prototype for New Understanding #2, 1998. Nike Air Jordans, hair, 23 x 21 x 25.5 cm, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Purchased with the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Vancouver Art Gallery Acquisition Fund.

Such is the problem currently faced by the Vancouver Art Gallery. There’s no denying that MashUp is an essential show in the history of art in Vancouver. Many of the works included are of daunting historical importance and beauty. And by its inclusion of Vancouver-based artists like Liz Magor, Brian Jungen, Geoffrey Farmer, Stan Douglas, and Amber Frid-Jimenez, MashUp makes a legitimate effort to enter its home city into the dominant art historical discourse. It is worth noting that, of the artists included in the first exhibition at the Vancouver Art Gallery’s current location, Vancouver: Art and Artists 1931-1983, none were included in MashUp. This is a clear example of how a gallery creates versions of history as it moves through time.[4]

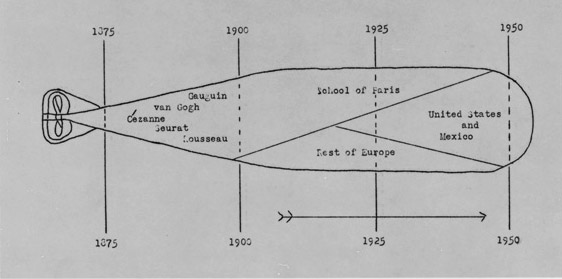

In this way, MashUp seems to adhere to the model of the torpedo in time, originally diagrammed by MoMA Founding Director Alfred H. Barr Jr. as a model for developing permanent collections, whereby the museum acts as a vessel moving forward through time. Where the tip of its nose breaks through the water is the present; the payload onboard is a representative sample of works that spans the length of modernity; and the trail of disruption left behind it in the water is the version of history the museum/torpedo requires us to observe.

Alfred H. Barr, Jr.’s “torpedo” diagrams of the ideal permanent collection of The Museum of Modern Art, 1941. Courtesy the Internet.

To arrange the exhibition chronologically from the top down seems at first to be a fundamentally conservative and Euro-centric decision. The top floor, devoted to the early 20th century includes European men almost exclusively. I raised this concern with organizing curator Stephanie Rebick in an interview we recorded in the Duchamp section of the exhibition. She explained:

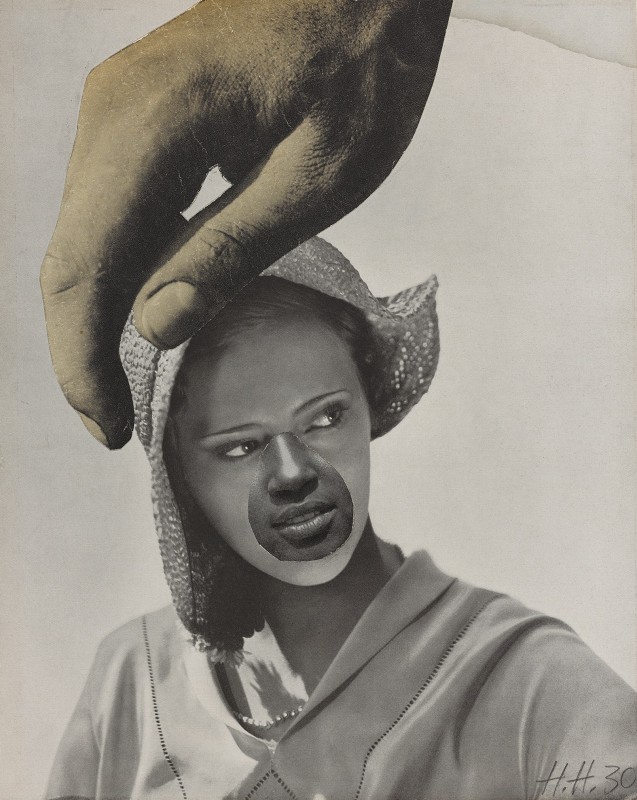

“In every section of the exhibition we tried to include issues of representation [of race and gender]… It was more challenging when you’re dealing with early 20th century artists to find females. Hannah Höch was really important for us to include because her work was one of the most influential and innovative of the time regardless of her gender. And it was interesting how she was working with ideas around the construction of gender in the 1920s and ‘30s, which was not really talked about as it is today. Her collaging images of this ‘new woman’ with images of older women in German society was quite revolutionary and political in a time when that was not necessarily accepted. She was one of the few female artists who was allowed to exhibit with the Dadaists. As you go to more contemporary sections, there is a broader selection of female artists that are doing really innovative things. It was something we thought about to try to represent different stories, histories, ideas, opinions…Tours and interpretations of materials come in to tell those histories. You’re not going to ignore the historical importance of someone like [Jean-Luc] Godard… but [we have] didactic material and tour guides prepped to address those issues. When you’re doing historical surveys, some of the most important works of art of the twentieth century, when we look back at them with our lens…some of that stuff doesn’t hold up in the best light. It doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t show it for the reasons it does hold up and acknowledge those issues.”

Hannah Höch, Untitled (Large Hand Over Woman’s Head), 1930. Photomontage, 25.7 x 20.7 cm, Collection Art Gallery of Ontario, purchase 2012

In this way, the exhibition asks us not only to read history as a straight line dotted with significant points, but also as a sea of ideas. Rebick went on, “we thought that we could potentially organize it by methodology. You could have potentially a collage section starting with Picasso, or assemblage, or film. But it’s such an overwhelming show to begin with that it seemed to make the most sense for our viewers to divide it up into these chronological sections… and show the different sorts of reactions, and leave it up to you to draw the connections.” So, let’s attempt to draw those connections between representations of gender, as an example. We will find that the idea traces a twisting path.

From Höch’s collages of female bodies, which interrogate the modes of physical and social oppression that limited the choices available to women in the first half of the twentieth century, we may move down to the third floor and watch Godard’s Pierrot le Fou (1965) in its entirety. As in many of his films, Godard portrays female sexuality as inherently sinister. He sees potential in his female subjects to be Madonnas, but usually in the end they are whores and betrayers. This was never more apparent than in Contempt (1963), which begins and ends with dissections of the character played by Brigitte Bardot. The didactic material around Pierrot le Fou asks us to consider the insert cuts of modern art works: Picasso, Lichtenstein, Chagall, Van Gogh (in many cases paintings of or about their muses) juxtaposed against a beating that Pierrot receives. This is a mashup, yes, but it is left to the audience to discern the intention: to entrench the dual role of muse and femme fatale. It is the prostitute’s fault Van Gogh cut off his ear; it is Marianne’s fault Pierrot kills himself.

Sherrie Levine, Fountain (After Marcel Duchamp), 1991, and Vikky Alexander, Obsession, 1983. Photo by Rachel Topham, courtesy of Vancouver Art Gallery.

Seeking a remedy to this mode of representation, we may move down to the second floor and find the display on 1980s drag culture and New York house music, or Sherrie Levine’s critical watercolour homages to modern art masterpieces, reminding us again of Léger, and (especially via the impassioned chauvinist Kazimir Malevich) the restrictions on women in early modern art.[5] We may move from this remedy to Jeff Koons’s regressive Pink Panther, (1988) before finally moving to the main floor and examining the state of identity politics in art today.

Amber Frid-Jimenez’s This is not a test (2016) is a multi-media sculptural installation that raises questions about the state of third wave feminism, interrogates the symbol of the mirror (which also features heavily in Dana Birnbaum’s Technology/Transformation: Wonder Woman (1978-79) on the third floor), and examines the insidious role of the Playboy bunny, putting generations of feminists: Gloria Steinem, Jessica Valenti, and Shulamith Firestone into dialogue with one another and with the evolution of new media. Frid-Jimenez clarified via email:

“This is not a test refers to a dialog between a post-feminist perspective (Nina Power, et al) and a third wave feminist one (Valenti, et al). I myself fall on the post-feminist side – Valenti espouses a kind of neo-liberalism that I can’t stand behind…

“Also, the face of Lena, the playboy centerfold in the piece, has been widely used since 1972 by computer scientists as a test image to develop image processing algorithms. Same as the bunny and ball but for 3D rendering.”

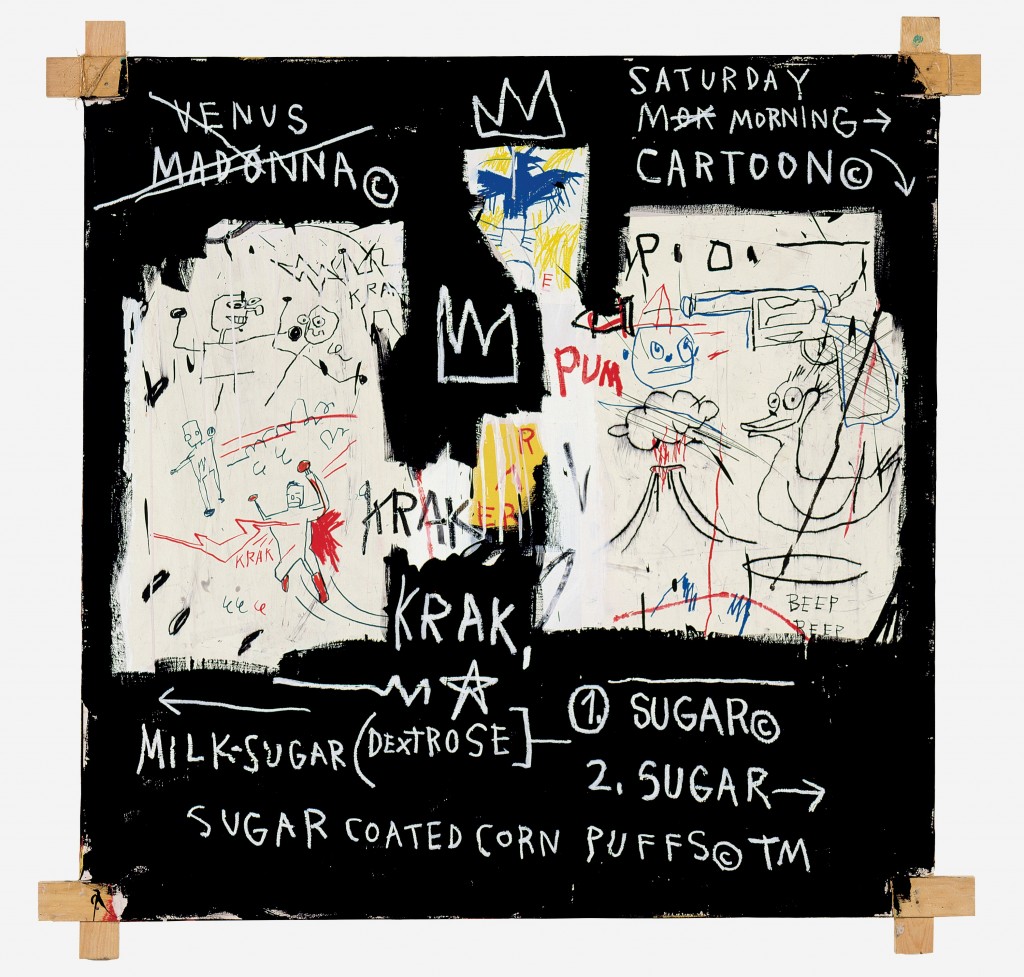

Jean-Michel Basquiat, A Panel of Experts, 1982, acrylic and oil pastel on canvas, 152 x 152.5cm, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Gift of Ira Young

I emailed contributing curator Melanie O’Brian for comment on Hito Steyerl’s work in the exhibition, Liquidity Inc. (2014), and she described it in part as “a hyper-intelligent critique of the power of images in circulation.” The work incorporates found footage, music, and a large blue foam and plywood wave that provides a lounge area in front of the screen. Its references include Andy Warhol, The Velvet Underground, and Hokusai, and it examines not only the fluidity of national identity created by globalization but also the “liquidity trap” in contemporary macroeconomics, which has amplified otherness through policies of austerity.[6]

The idea of austerity—the renaming of an economic degradation as preservation—is a conceptual foil for Steyerl’s idea of the poor image. In her 2009 text In Defense of the Poor Image, Steyerl writes about the proliferation of degraded and manipulated digital images, “the history of conceptual art describes this dematerialization of the art object first as a resistant move against the fetish value of visibility. Then, however, the dematerialized art object turns out to be perfectly adapted to the semioticization of capital, and thus to the conceptual turn of capitalism.”[7]

Steyerl further raises the possibility that Godard’s art is problematic as a function of its medium: “…high-end economies of film production were (and still are) firmly anchored in systems of national culture, capitalist studio production, the cult of mostly male genius, and the original version, and thus are often conservative in their very structure.”[8] The dislocation of Godard’s original into a digital format, projected in a small room, in a gallery instead of a cinema, viewed mostly in random clips by passing audience members, seems to encourage this reading.

O’Brian wrote, “The VAG specifically asked me to curate work by Hito Steyerl as I recently worked with her on an exhibition at the Audain Gallery—we showed Adorno’s Grey in 2013. At SFU, the work opened up a series of questions about the construction of history, the space of the university and dialogues between activism and art… In addition, the mantra of Steyerl’s work in [MashUp], ‘Be Water,’ speaks to a demanded resiliency in the shifting economies of politics, finance, culture and environment… a shifting terrain that demands ongoing interrogations by audiences.”

Installation view of Ellen Gallagher, Pomp-Bang, 2003. Plasticine, ink and paper mounted on canvas, 244 x 488 cm, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Joseph and Jory Shapiro Fund by exchange and restricted gift of Sara Szold. Photo by Aya Garcia.

Thus, tracing the history of representations of women in art is just one stream of an idea that can be followed up and down through MashUp. From the rotunda, Barbara Kruger’s installation screams at Guy Debord, “LIFE IS NOT A SPECTACLE”; in their Video Tape Study No. 3, 1967-9, Nam June Paik and Jud Yalkut offer Marshall McLuhan’s seminal view on the interpretation of media: “every time a new medium arrives, the old medium is the content…the massaging is done by the new medium and it is ignored”; and a handful of works such as Ellen Gallagher’s yellow plasticine recreations of black hairstyles, Pomp-Bang (2003) and Brian Jungen’s series of Haida masks made from dismantled Air Jordans and human hair, Prototypes for New Understanding (1998-2005), offer arresting statements on racial identity and cultural heritage. And so MashUp tosses its audience into this maelstrom, and leaves them to paddle through their own histories: of political dissent, of the evolution of new media, of aesthetics, of race, of the identity of the artist, of gender, of literature, of film, of architecture and design, and so on and so on…

—

[1] We do know that Léger excludes the anecdote from his 1914 essay “Contemporary Achievements in Painting” in which he concludes “…you can advantageously substitute the most banal, worn-out subject, like a nude in a studio and a thousand others, for locomotives and other modern engines that are difficult to pose in one’s studio.” And the didactic material at a recent Vancouver Art Gallery retrospective offers Jerry Pethick’s (probably erroneous) claim that the propeller in question was the one designed by Ludwig Wittgenstein with tiny motors on the tips of the blades—his singular contribution to aviation engineering. The reverence we now pay to Duchamp’s readymades is ultimately belied by Duchamp’s own defence of the Fountain (1917) in a contemporaneous article entitled “The Richard Mutt Case” where he argues that, “the only works of art America has given are her plumbing and her bridges.” He really was, it seems, taking the piss.

[2] Benjamin, Walter. “Provinzial-Museum.” Recent Writings. New Documents, 2013. Vancouver, Canada. 48-51

[3] The co-opting of Benjamin’s identity as a critique of contemporary curation is discussed in the LA Review of Books. April 21, 2014. lareviewofbooks.org/review/walter-benjamin-writings-death

[4] Rombout, Luke et al. The Vancouver Art Gallery. Vancouver: Art and Artists 1931-1983. exhibition catalogue. October 15 – December 31, 1983.

[5] For Malevich’s opinions on the supremacy of Russians and men especially, see any of his early essays. For an overview of the role of women in modern art see Enrique Vila-Matas’s Brief History of Portable Literature (1985) or Ludmila Uliskaya’s Big Green Tent (2014).

[6] For a quick introduction to the benefits of deficit spending in a liquidity trap and the dangers of austerity, see Paul Krugman’s New York Times blog post “Self-Defeating Austerity” (July 7, 2010), krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/07/07/self-defeating-austerity/?_r=0

[7] Steyerl, Hito. “In Defense of the Poor Image.” E-flux. 11/2009 www.e-flux.com/journal/in-defense-of-the-poor-image/

[8] Ibid