Leah Rosenberg: Color and Scale

Black & White Projects

Pacific Felt Factory Arts Complex

2830 20th Street, No. 105, San Francisco CA 94110

February 5 – March 5, 2016

Like a lot of people, Leah Rosenberg takes walks, or rides her bike around town. As one’s routine takes hold, many things may pass unnoticed during the banal or stressful treks to work, shuttling kids around town, or running countless errands. Not for Rosenberg: her journeys are purposeful and fodder for making art. Throughout her daily travels, different colors pass her gaze, each harboring a poignant story of its whereabouts or the people and things that make it stand out for her. These observations are just one step in an interdisciplinary practice that encompasses photography, writing, painting, public interventions, ephemera, and even baking cakes.

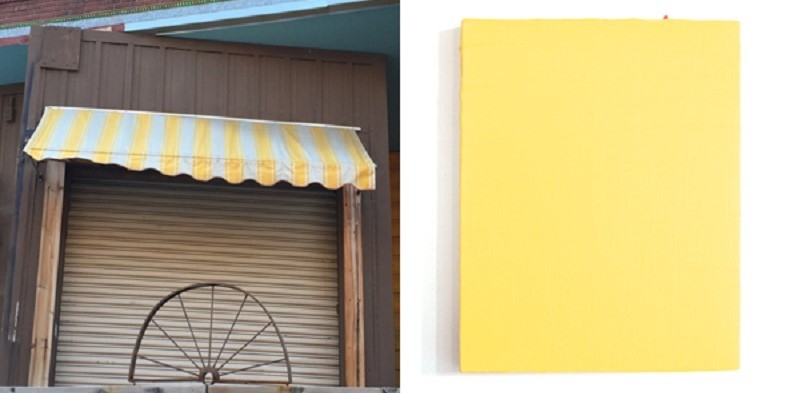

Leah Rosenberg, 100 Days of Color (from #CHROMAHA), 2015. “Day 18// The antique candy stop’s yellow striped canopy,” poem, documentation and coinciding color. Courtesy of the artist.

Recently Rosenberg attended a residency at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Omaha, Nebraska. She titled the project Chromaha, a playful pun of the project and a nod to the city where it took place. For 100 days during her time there, she found and documented colors from experiences, things or places: the yellow awning of a candy store, too much almond milk in her tea, a hot pink ribbon tied to a tree. She wrote coinciding poems for each color that read as diaristic notes and observations: (palest mint green) the light comes through the curtains, so faint; (blue) rolls of blue 3M tape used to mask off each stripe; (bright teal) a pair of high heels caught my eye at the opening of Go West. In conjunction with these daily musings and color gathering, Rosenberg would head to the local hardware store to buy paint in the corresponding hues that she needed. She then painted 100 wood panels.

Her website chronicles the process. The colors were applied to the 100 panels in succession; each new color beginning with the following panel. For example, the first color was applied to all 100 panels. The second color was applied to the second panel, and all remaining 98 panels; the third color is applied to the third panel and all subsequent 96 panels and so on. The final panel includes all 100 colors. Tended to on bended knee, the panels were laid out on the floor to be worked on. The act of accretion—building of layers from one piece to the next—becomes a somewhat meditative activity, void of the intuition and act of looking that the gathering entails.

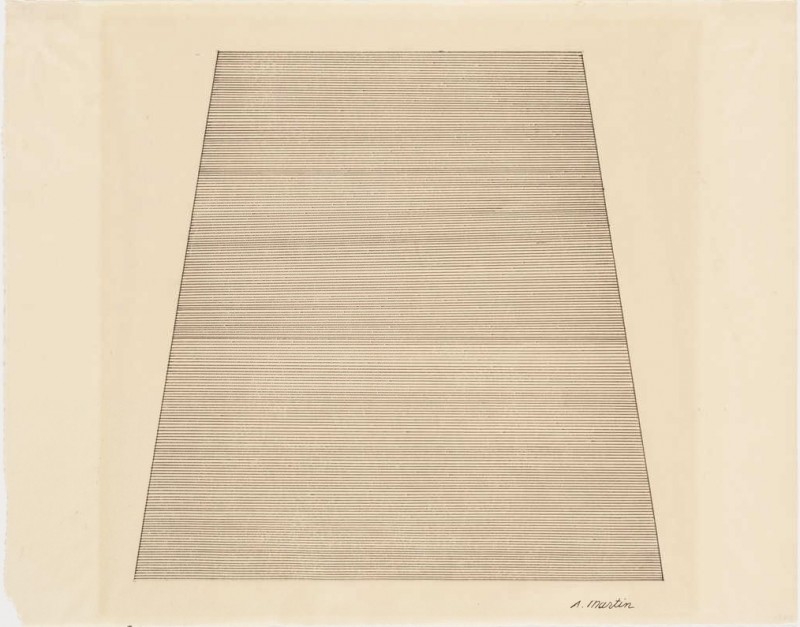

Agnes Martin, Mountain, (1960). Courtesy of MoMA

During the painting process, the paint pours over the sides. A progression occurs when more layers are added to each panel. As it piles up, the paint no longer streams down the sides but instead begins to pool at the sides, resulting in dimensional scalloped edges. Even though the process is formulaic, she uses traditional tools to apply paint, such as brushes or sponges, which indicate the artist’s hand. Each piece is unique and painterly as a result of the paint’s natural behavior to drip and pool, as well as the noticeable brush strokes on the surface. Her systematic meditation coupled with the tactile surfaces and overall minimal aesthetic is akin to Agnes Martin’s later monochromatic works, though more vibrant than Martin’s serene results. Martin assimilated with the minimalist mannerism popular in the 1960s, but she also set herself apart from the common stoic and hard-edge sensibility through her relationship with Buddhism and Taoism, which emphasizes the beauty and poignancy of one’s surroundings.[1] Rather than emphasizing the dogma of contemporary art, Martin looked to life for inspiration. Rosenberg’s work is also more about life than it is about the act of painting. Although her work might appear to some as simply the task of applying color to each panel, the real work is about responding to her surroundings through the meditation of painting and the ritual of journaling.

The entire 100 paintings, titled 100 Days of Color (from #CHROMAHA) (2015), are currently on display at Black and White Projects. The paintings are hung in a large grid formation on two adjacent walls, from top to bottom, and left to right in the order they were painted. The space is small, so the installation is striking, filling up almost the entire span of wall that is available. There is a shallow column that bisects part of the installation, which can be distracting to some who might prefer a more pristine and completely unified grid. On the other hand, it also works well when considering the industrial quality of the grid formation, and the humble house paints Rosenberg used. Though the works are small, they are not in the least bit precious, and instead seem quite integrated here as a poetic chronology of everyday events and thoughts.

Leah Rosenberg,142 Pounds of Paint, 2013. Acrylic, 21″ x 15″ x 15″. Courtesy of the artist and Black and White Projects. Photo: LLutz

Opposite the installation is a large industrial scale that was used for weighing materials, parcels, and other objects when the building was a felt factory. The large numerical face of the scale points to the number 142. The heavy-duty spring scales are installed in the floor, covered by a large metal plate where, the piece 142 Pounds of Paint (2013) is installed. The piece is comprised of hundreds of layers of paint which have been peeled from their original substrate and arranged in two slumping piles. The piles of peeled paint seem like large books, as if the pages are a leaf in an action painting. These works act as time-based pieces as do the chronological color paintings and poems. Rosenberg frequently works on poured pieces, allowing the paint to dry and then peeling it up to adhere to substrates, or to create stacks or balls. Lynda Benglis’s poured works come to mind, not only for similar process but also the use of industrial or house paint.

Leah Rosenberg,142 Pounds of Paint, 2013 (detail). Acrylic, 21″ x 15″ x 15″. Courtesy of the artist and Black and White Projects. Photo: LLutz

Chromaha is a continuation of a previous installation done for Irving Street Projects, titled Everyday, A Color. In both projects, the work is about more than color; they are about taking stock of the little things that are taken for granted. Rosenberg is also deeply committed to making sure her work involves the community where the projects took place. For Chromaha she made colored magnets that people could take and place wherever they wished in the community; for Everyday she made buttons for people to wear. She also makes limited edition prints for each project as a way of offering more accessible works. Not only does Rosenberg make art objects, but she also bakes cakes, which in her case are art objects too. She incorporates the act of making and serving in her projects by baking cakes and offering them for visitors to eat. The act of eating together creates communal harmony and interaction, enjoyment and perhaps even nostalgia—as many of the cakes are more fanciful than any deep childhood memory could ever conjure. On Friday, February 26th, Rosenberg launched new limited editions print in tandem with the exhibition, created at a residency at Kala Institute. She also served pound cake(s) that she personally baked for the event, in conjunction with the 142 Pounds of Paint work. Rosenberg’s thoughtful and inclusive practice involves so many different layers by tapping into visual and taste senses, while also conjuring memory and the importance of togetherness. Rosenberg is not just gathering color; she is gathering the psyche of what brings color to the lives of people.

Leah Rosenberg, 100 Days of Color (from #CHROMAHA), 2015. Acrylic paint, 100 panels, 10″ x 8″ each, installation, 62″ x 233.” Courtesy of the artist and Black and White Projects. Photo: LLutz

Black and White Projects is a new space curated by Rhiannon MacFadyen. It is located in an industrial space in the newly renovated and reopened Pacific Felt Factory building, which houses several artist studios, flex space and common facilities. Formerly ACS Projects, Color and Scale is their inaugural exhibition for their new iteration, and includes a limited edition print In the Beginning: A Black and White Project (2016), a two-color silkscreen for sale by Rosenberg.

—

[1] Haskell, Barbara. Agnes Martin, Whitney Museum of Art, New York: Harry Abrams, 1992, 137.