Language of the Birds: Occult and Art

80WSE Gallery, New York University

80 Washington Square E, New York, NY 10003

January 12 – February 13, 2016

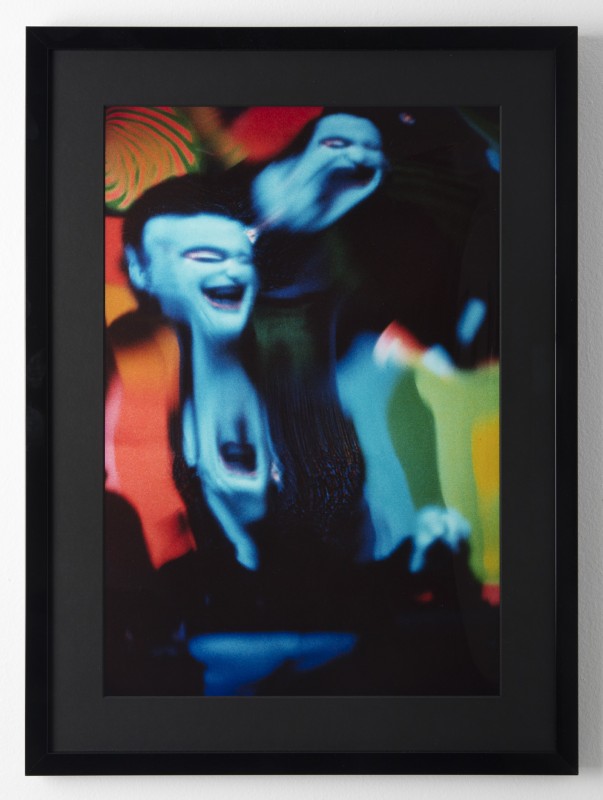

Freaky blue witches laugh at you from their warped mirror world, taunting you for missing out on whatever dark pleasures they’re indulging. Ira Cohen’s Dr. Mabuse—much like the other works in this exhibition—is a window to the world of the occult and, as with all such windows, it’s either a mirror itself, or smudged by those who don’t want you to see.

At first thought, there seems inherent risk in putting on an exhibition about the occult, since the term seeks escape from view: the “occult,” after all, consists of hidden knowledge and practices, reserved only for the initiated, allowing comprehension and manipulation of the cosmos and the self. Meanwhile, an exhibition at NYU’s 80WSE gallery in the Lower East Side is maybe the least occult thing one could imagine.

Or is it?

Ira Cohen, Dr. Mabuse, 1966-70. Photo credit: Jean Vong for 80WSE Gallery

Language of the Birds: Occult and Art, curated by Pam Grossman, is a wide-ranging display of esoteric constitutions. High and low registers of magic, as described in the exhibition’s text, are placed side by side—the ceremonial, Christianized “high” magic of religious myth and ritual, as well as the Chthonic, “low” magic of witchcraft, connected to the Earth and its substances. The exhibition runs the gamut of Kabbalistic text, demon figures, astrological signage, talismans and potions and amulets, transmogrifications of the human form, death and its incarnations, mystical numerology, et al.

Besides the mix of different forms of occult, it’s a mix of art brows as well. There’s a kitschy Lucifer with eyes-for-pecs, by the Australian painter and covenist Rosaleen Norton; Kiki Smith’s Sirens, little human-headed birds of bronze that recall the mythical Greek bird-women who lured sailors to shipwreck with their songs; BREYER P-ORRIDGE’s x-ray-like image of two arms with eyes in the palms of their hands, signifying the Hamsa, defenses against the evil eye.

Installation view of Language and the Birds: Occult and Art at 80WSE Gallery, New York University, January 12 – February 13, 2016. Photo credit: Jean Vong for 80WSE Gallery

The wall text serves to divide and classify the rooms (COSMOS: Portals*Systems*Maps, SPIRITS: Forces*Entities*Deities). If it sounds a bit buzzwordy, it’s because it kinda is. Though it comes off as non-clandestine, cloistering even, the text aids in thinking through the many layers of the subject at hand. Most importantly perhaps, the exhibition reveals the “occult” as a modern cultural phenomenon, something that persisted through the 20th century’s sharp turn to technology and rational materialism, contributed greatly to the rise of popular and counter culture, and which continues today in the digital world.

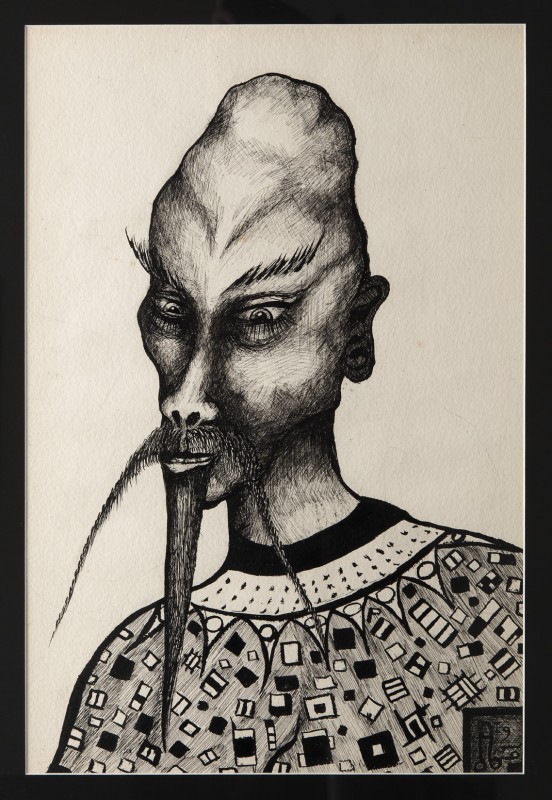

Aleister Crowley, Kwaw (Idealized Self-portrait), 1935. Photo credit: Jean Vong for 80WSE Gallery

The individual works pay great credence to both the fin-de-siècle and more modern history of occult practices impinging on cultural daylight. Artist Jesse Bransford invokes the history of the occult in New York, with a photo of Surrealist artists Kurt Seligmann and Enrico Donati atop a magic circle in Seligmann’s Bryant Park apartment in 1948, and also recreates the circle with an altar in the gallery. Also in the exhibition is a beautifully creepy “self portrait” by Aleister Crowley, perhaps the most well-known occultist, as his alter ago Master Kwaw, multi-foreheaded and with a Fu Manchu mustache and all. (Kwaw, i.e. Crowley, according to Crowley’s book Konx Om Pax, was a Taoist advisor to the Japanese daimio who taught alternate tendencies—chastity to prostitutes, sexual expression for the prudish, ceremonial magick to Atheists.)

Bernard Hoffman, “Kurt Seligmann and Enrico Donati in a ‘Magic Circle’” 1948, gelatin silver print of “Magic Evening” (Soirée Seligmann). Courtesy Seligmann Center at the Orange County Citizens Foundation.

Indeed, the “occult” is intimately woven into the history of popular and counter culture—Crowley, notoriously esoteric and aligned with the devil, drugs, and bisexuality, was voted the 63rd Greatest Briton in a BBC poll. Language of the Birds embraces the cultural commodification of the occult, but it also helps to think about the complexity of occult practices, such as magic: primitive and pre-rational, magic is a bedrock of human experience. It grants power to the object, which in turn grants power to subjects. It’s fundamental not just to religious experience, but also to scientific inquiry, especially the foundations of medicine.[1] Beyond that, the Internet and virtual reality might be thought of as magic incarnate.

But what of the commercialization of occult practices, the kind done by corporations, the illegitimate posturing by en vogue gentrifier covens, mystics, and bro-cults?

Across time, culture, and mythology, birds have been thought to be the carriers of divinity, associated with perfect knowledge—and magic, sorcery, or summoning has been the means to communicate with them. Getting back to the first question posed here, in a society bent on discovery and exposure, where science seeks to explain the universe, and where capitalism seeks to extract effort, time, and attention from every nook and cranny—what can possibly remain occult?

In Manhattan, a most visible cradle of civilization, the magic of the market and mysteries of dark finance plot a course of indulgent pleasure along a path of collapse. Inaccessible wealth, power, and control emanate over the entire Earth and beyond. Perhaps this is the most occult thing of all.

—

[1] Mauss, Marcel, Robert Brain, and David Francis Pocock. A General Theory of Magic. London: Routledge, 2001.