from here to there: kurimanzutto travels to Jessica Silverman Gallery

Jessica Silverman Gallery

488 Ellis St, San Francisco, CA 94102

January 12–March 5, 2016

“Something definitively unfinished, something that is building itself forever: fragmentary, contradictory, weak, unstable, dark, transparent, warm, stupid, delirious, chaotic, crippled. It’s movement and life, it’s love, it’s sex, it’s me.” –Abraham Cruzvillegas (expanding on the intellectual investigation of his own paradoxical aesthetic concepts of autoconstrucción and autodestrucción)

José Kuri, Mónica Manzutto, and Gabriel Orozco founded kurimanzutto in 1999. Manzutto was working at the trend-setting Marion Goodman Gallery in New York City where she and Kuri and Orozco were living and studying. Orozco suggested they open a gallery in Mexico City and call it kurimanzutto. It had no fixed address and its inaugural show, Market Economies, was in a stall at a produce market, the show consisting of works sold at produce market prices. Non-traditional venues became the norm: an old movie theater, a carpet showroom, and an airport terminal. Having limited funds, Kuri and Manzutto decided to forego a brick and mortar gallery and traveling to meet curators and to attend art fairs. Abraham Cruzvillegas, Damián Ortega, Gabriel Kuri, and Dr Lakra all attended Orozco’s Friday workshops of discussion and late night drinking from 1987 to 1992 and became part of kurimanzutto. With its lower case k, kurimanzutto now includes both international artists and artists with deep roots in Mexico City. kurimanzutto has popped up in Paris, Warsaw, and other European cities, and has now traveled to San Francisco to the Jessica Silverman Gallery.

Daniel Guzmán, New York Groove, 2004. Video transferred to DVD 3 min. Courtesy of the artist, kurimanzutto and Jessica Silverman Gallery

The gallery occupies a large corner space, in a building owned by Mercy Housing, a nonprofit housing development, in San Francisco’s low income Tenderloin: a part of the city where refugees and the homeless rub elbows with wealthy techies. It is a fitting location for this show. from here to there is a massive exhibit by 16 of kurimanzutto’s 33 artists. The work in the exhibition ranges from installation, paintings, drawings, found objects and photography, videos, and features both new and historical works by these conceptual, socially minded, and iconoclastic artists.

As I entered, I immediately encountered Roman Ondak’s absurdist “Flag” (2015) made of a lead pipe and paint and Jimmie Durham’s portable Arc de Triomphe for Personal Use (2015). Durham’s riff on historical monuments, specifically referencing one which is the very symbol of France, is especially ironic as France and the European Union countries close their borders to war refugees, and alludes the recent destruction by ISIS of the Arch of Triumph in the ancient city of Palmyra.

Minerva Cuevas, Oreja RX, 2015. Chocolate and silkscreen on cardboard box. 20 x 28 x 28 cm. (7.87 x 11.02 x 11.02 i.) installed. Courtesy of the artist, kurimanzutto and Jessica Silverman Gallery

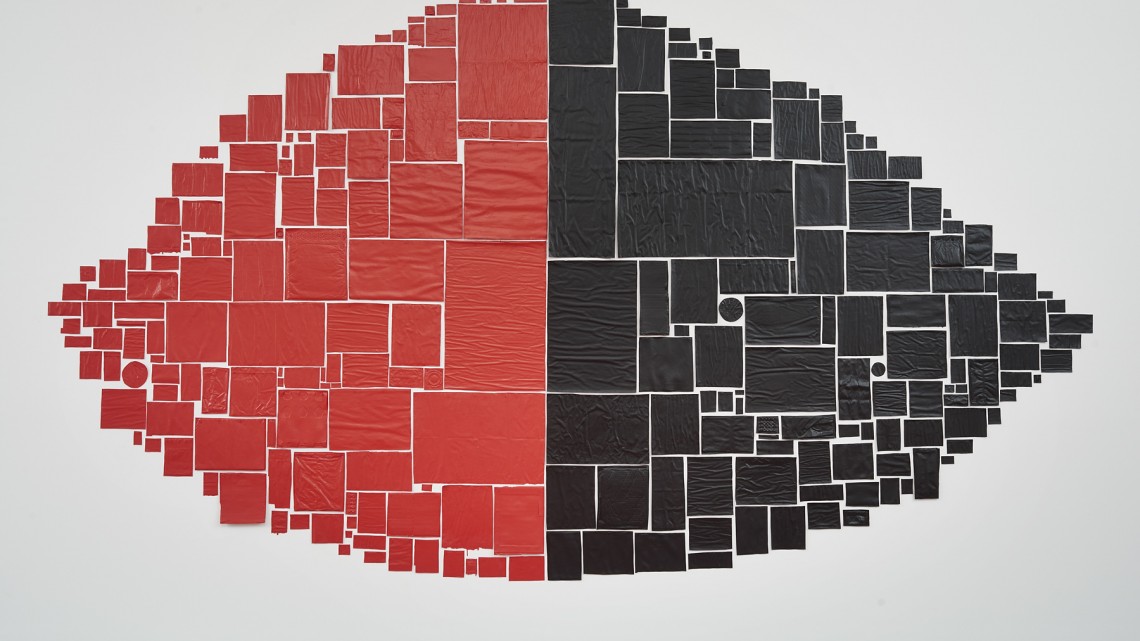

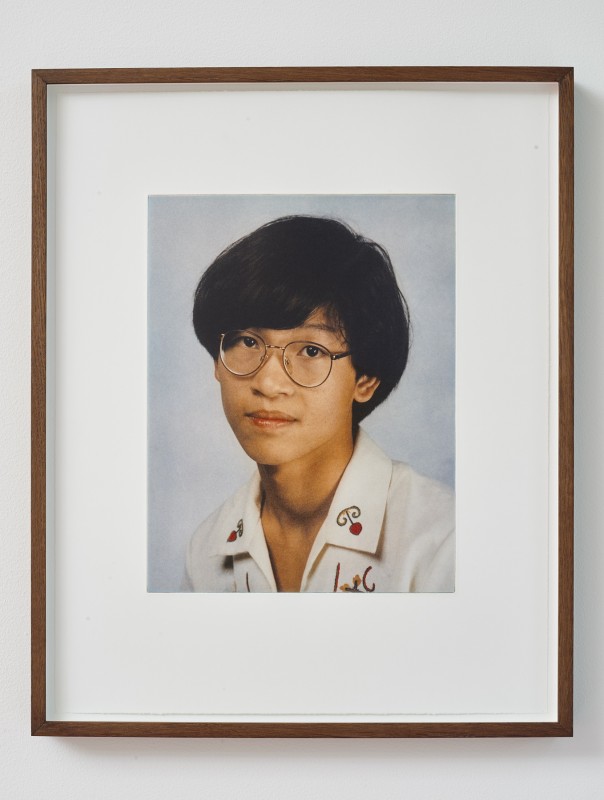

Minerva Cuevas’s two pieces include Oreja RX 2015 (2015): a limited edition of chocolate ears and Evil Time (2015), consisting of a white sign of big red letters, turned sideways in the gallery window, which seems simultaneously to spell out “time” and “evil.” Dismembered ears made of cacao, a substance that was vital to the spiritual and cultural life of the Mayan people and which is now part of the fabric of global export seems to abjure the current (and historical) violence in Mexico and Latin America and are packaged in attractive gift boxes, something “sweet” for international consumption, and are for sale at the front desk. Abraham Cruzvillegas’s large untitled wall piece made in 2016, consists of 456 pieces of ephemera pinned to the wall: things such as newspapers, tickets, and envelopes, their backs painted black and red (you can lift them up and see what’s on the other side). Autoconstrucción is a philosophical concept Cruzvillegas uses to describe his improvised method of building things. He was deeply influenced by the working class suburb of Mexico City where he grew up in the 1960s. Formed by economic migrants from the countryside, the residents built their own dwellings and sense of community in spite of the chaos and fragmentation of their lives. Several carmine rugs presented by Danh Vo dominate the gallery floor and visually tie the show together. Through a mix of historical research, and collaboration, the rugs are made by a family of traditional Mexican weavers and colored with a dye made from the cochineal beetle, an important export during the Spanish colonial period in Mexico. To this, Vo adds his own complicated history (a South Vietnamese refugee who grew up in Denmark) by exhibiting an awkward teenaged photo portrait of himself.

Danh Vo. Untitled (Self-portrait as Carrie), 2015. Photogravure print. Image: 13.6 x 10.6 inches / 34.5 x 27 cm. Paper: 21.3 x 16.9 inches / 54 x 43 cm. Courtesy of the artist, kurimanzutto and Jessica Silverman Gallery

Leonor Antunes’s large black and white tapestry, Anni (2015), made of leather and cotton is an homage to Bauhaus artist Anni Albers and her work at Black Mountain College. Antunes echoes Albers’s emphasis on handicraft and on unorthodox materials, such as textiles from the ancient Americas married to a Modernist grid. And I suspect that ‘Anni’ refers to the history of women’s art and work, which was often attributed to “Anonymous.”

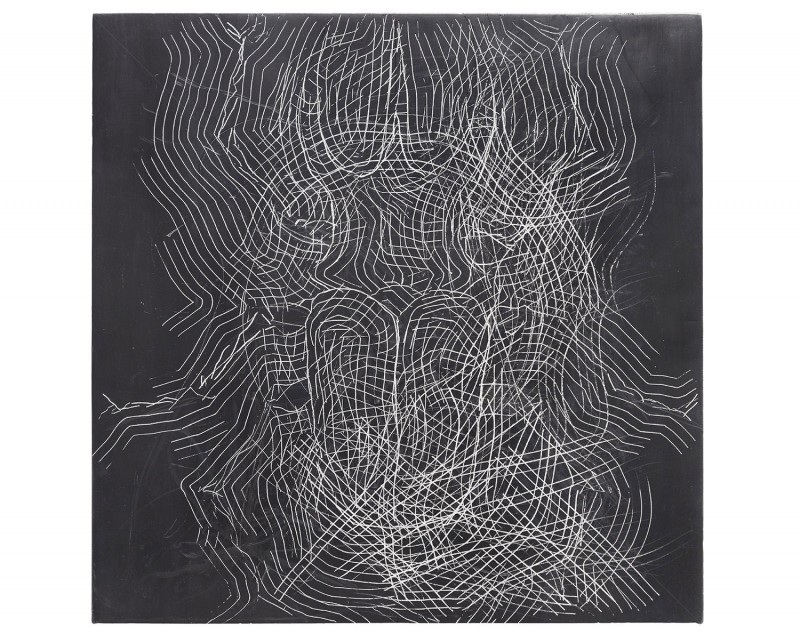

On the main gallery’s back wall are Gabriel Orozco’s series of drawings of indigenous Mexican beetles (made by scraping white lines into graphite panels) and a series of prints of his own hands combined with rubbings of leaves. Nearby, a vignette of a lump of terracotta on a worn wooden work bench means to evoke Orozco’s studio. Next to this is Gabriel Kuri’s oversized still life, which could be a surrealist proposition or concrete poem of objects—some recognizable (giant matches, a giant coffee bean), some obscure, like a piece of volcanic rock. Next to this are two large silkscreens by Allora & Calzadilla, who live and work in Puerto Rico, depicting beautiful tropical palm trees, also the U.S. Navy’s way to mark toxic waste sites on their Naval Training Range on occupied Vieques Island.

Gabriel Orozco, Untitled, 2015. From set of 4. Graphite on gesso. 15.75 x 15.75 inches / 40 x 40 cm each. Courtesy of the artist, kurimanzutto and Jessica Silverman Gallery

The exhibition extends beyond the main gallery space and into the bathroom, kitchen, and back office. In the hallway crazy life drawings morph into ancient Toltec gods in Chromosome Damage, a recent series of grotesquely funny drawings by Daniel Guzmán. At the end of the hall are two video monitors stacked on top of each other—the top showing New York Groove (2004), a short video where Guzmán frolics down a New York street like a pied piper, attracting some people and amusing others, and the bottom showing Objeto de limpieza (1993), a short video which appears to be a send-up of classic slow-moving performance art pieces. Shot in black and white, he attempts to wash himself with a bar of soap without using his hands. When we duck into the bathroom and kitchen, we find Dr Lakra (“the delinquent” in Spanish). Flea markets, the bloody Christs found in all Mexican Catholic churches, comic books, pornography, prison tattoos: these all contribute to his gothic bad taste. His untitled series of vintage 1950s cheesecake pin-ups are modified into explicit, disturbing images of bondage at the hands of silhouettes of Posada meurtos and devils and monsters.

Daniel Guzmán, Sin título. De la serie: “Chromosome Damage”, 2014. Pastel, charcoal and acrylic on paper. Dimensions: 25.2 x 17.3 inches / 64 x 44 cm. Framed Dimensions: 28 x 20.1 x 1.8 inches / 71.2 x 51.2 x 4.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist, kurimanzutto and Jessica Silverman Gallery

I leave the gallery and reflect how the history of kurimanzutto mirrors the changing social and economic fabric of Mexico City. kurimanzutto is located in Contessa, one of the artsy neighborhoods clustered around Chapultepec Park. With a population of over twenty million, Mexico City is a city of extreme wealth and poverty, where sophistication and the quotidian exist side-by-side; where next to ancient pyramids of the sun and the moon of Teotihuacan is a Walmart de Mexico; where smog mixes with the smoke from Popocatépetl active volcano; where it costs about $.20 to ride the subway; where a former industrial zone is now home to two new billionaire-funded museums and several international corporate headquarters; where, in the Centro Histórico, pierced and tattooed chilangos sell Chinese superhero toys; and where striking teachers and citizens protest corruption and violence in the Zocalo. Fueled by leftist leanings, socially minded, humorous, humane, preoccupied with mortality and, often, the grotesque, the contemporary artists in from here to there mix old with new and make completely original art. The traditions of the great Mexican muralists and graphic artists live on in kurimanzutto’s nostalgia for the analogue, for books and printing, for handmade items, and for craft. These thoughts fall away as I pass the food line at Glide Memorial Church, the sidewalk filled with the poor and with tech workers navigating “The Loin” with $600 cellphones, the latest laptops snug in their briefcases.

—

**Title inspired by Robert Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives (Los Detectives Salvajes). Trans. Natasha Wimmer. New York. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007.