Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet

Fort Mason Center for Arts + Culture, Gallery 308, San Francisco CA

November 14, 2015 – January 18, 2016

Janet Cardiff’s installation The Forty Part Motet is a rare instance of a contemporary artwork that has been shown a number of times over more than a decade to seemingly universal acclaim, including testaments to its emotional power. The current iteration of the piece at San Francisco’s Gallery 308 at Fort Mason has brought one local art critic to a state of near weeping, and another to launch a short homily on how the piece shows us the possibility of humanizing technology.[1] Cardiff’s piece has some of the qualities of the most popular works of contemporary art, such as Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate (2006) in Chicago and Olafur Elliasson’s The Weather Project (2003) in London, by offering an inexhaustibly rich and sensuous surface that shifts in response to the viewer’s free self-positioning and movements. Cardiff’s work differs from these two primarily visual works by inducing a passage from sight to sound, and recruiting into the work something of the phantasy that, through listening, something of what emits the sound is simultaneously within us.

Janet Cardiff, The Forty Part Motet (installation view, Gallery 308, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture), 2015; co-presented by Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: JKA Photography

Cardiff’s piece is a spatialized realization of the 16th century English composer Thomas Tallis’s ever-astonishing masterwork Spem in alium, a highly polyphonic choral piece for 40 voices. The collective voices are divided into eight 5-part choirs, each consisting of an alto, a contralto, a tenor, and two basses. In much of the work, usually about nine-and-a-half minutes in performance, individual choirs enter and leave the general texture individually, creating the sense of a kind of articulated moving cloud of sound, with internal articulations provided by responsive antiphonies and the play of the ethereal high G’s of the sopranos against the range of male voices. The whole is dramatically punctuated by tuttis, the first underlining the power of God, then urging Him to mindfulness of his creatures. Cardiff’s conceit is to record a performance of the motet with the singers individually miked and to assign each voice to one of 40 black speakers, each mounted on a black pole. The speakers are distributed evenly in a large circle, with larger spaces between every fifth speaker to articulate the eight choral groups. The piece is played twice every half hour, with some three minutes of subdued small talk punctuating the performances.

Cardiff has said that the piece is about intimacy; indeed, it evidently induces such a sense when the viewer is irresistibly drawn up quite close to one of the anthropomorphic speakers and can make out an individual voice. Many viewers turn one ear to the speaker, thereby making the minor sacrifice of visual contact with the uninteresting visuality of the speaker in the service of becoming a listener, not just of a musical voice, but more of a human voice. The spatiality of the piece falls away, and one hears the soft individual voice set against the moving background of collective voices.

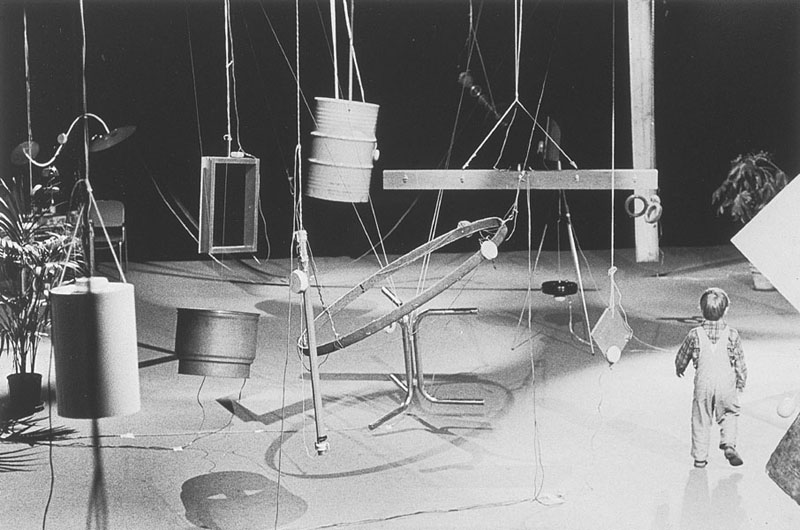

Installation of Rainforest IV (1973), L’Espace Pierre Cardin, Paris,1976, gelatin silver print. Photograph by Ralph Jones (American, b. 1951). Courtesy of The J. Paul Getty Trust

The experience thereby generated is certainly powerful. In a kind of willed drifting, the viewer isolates herself and identifies another, listening to the voice as one would listen to someone whispering into one’s ear. Tallis’s work becomes a background: there are eight million stories in the naked city, 40 voices in the motet, and this is one of them. But it seems to me that there is a further feature that contributes to the explanation of why this work has had and continues to have such resonance. Consider a great precursor to Cardiff’s piece, David Tudor’s Rainforest IV (1973), another piece that has been realized many times. This earlier piece was a late product of experimental modernism, namely the non-hierarchical and chance poetics of Merce Cunningham and John Cage (of whose music Tudor was a great exponent as a virtuoso pianist). In Tudor’s piece, which he called ‘an electro-acoustic environment,’ a large number of seemingly salvaged bits of metallic jetsam are randomly arranged about a large space. Each cluster emits some soft stream of sub-meaningful noises, mechanical chirpings, hisses, or clangs. As in Cardiff’s piece, the viewer is induced to wander without goal, listening, looking, focusing and un-focusing. But this realization of a catchphrase of Cage’s and Cunningham’s poetics—‘every seat is the best’—gives Rainforest IV two kinds of expressive power that are blocked in Cardiff’s overwhelming concern to generate the sense of intimacy: (a) in Tudor’s piece, both the sounds and the quasi-sculptural sound sources maintain a kind of ‘other-than-human’ quality, so that the fantasy of dissolving oneself into the other cannot arise, and instead the viewer is challenged to attune herself to ongoing contingencies; (b) likewise, in Rainforest IV the entire space of the installation, itself only loosely bounded, becomes charged with possibilities of visual and aural exploration and thereby solicits the viewer’s interest in imagining ways of ordering or making sense of the material; whereas in Cardiff’s piece the area between the two zones that attract the viewer—on the one hand the ‘intimacy’ zone next to the speakers, and on the other hand the center at which all speakers point and which becomes the ideal listening point to grasp the whole composition—is simply an area that one passes through; the middle range neither provides intimacy nor allows attuned engagement with Tallis’s incomparably intricate architectures.

Janet Cardiff, The Forty Part Motet (installation view, Gallery 308, Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture), 2015; co-presented by Fort Mason Center for Arts & Culture and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; photo: JKA Photography

In contrast to Cardiff annihilating the possibility of the viewer grasping or creating structures of meaningfulness greater than the intimate dyad and less than the full motet, Tudor generates the sense that the viewer-listener’s attention itself generates simultaneously small-, medium-, and large-scale orders and offers a further inexhaustible range of interactions among these orders. This is no decisive reason to favor the earlier work. Perhaps part of the unsettling power of Cardiff’s piece is its expression of contemporary life as a (hopefully) temporary defeat of the social imagination, our inability to create the new kinds of meaningfulness between the intimate and the impersonal collective. The Forty Part Motet perhaps acknowledges this condition, though it refrains from suggesting a way out of it.

—

[1] Sarah Hotchkiss and Charles Desmarais respectively, in KQED and the San Francisco Chronicle.