The Mapmaker’s Dream: Marius Bercea, Maurizio Anzeri, Linda Connor, Chris McCaw, Pae White.

Haines Gallery

49 Geary Street, Suite 540, San Francisco, CA 94108

November 5 – December 23, 2015

In Rebecca Solnit’s Infinite City, she meditates on the meaning of place, and defines a human being as a living atlas, each of us the sum of our personal experiences as we map (and thus embody) our environment. Historically—using materials such as rock, parchment, and paper—mapmaking combines aesthetics, science, and design to communicate a particular topography that may be physical, abstract, or even mythological. The Mapmaker’s Dream, a group exhibition at Haines Gallery, communicates such topographies with non-traditional materials: landscape painting, embroidered and solarized photographs, computer printing, and digital 3-D animation. The exhibition plays with the idea of the artist as wanderer, and art’s intrinsic alchemy as a device to navigate time, memory, history, and longing.

Marius Bercea, Recipe for Tuesday Sunsets, 2015. Oil on canvas, 46 x 75 inches. Courtesy the artist and Haines Gallery

Marius Bercea recently traveled around Los Angeles and its surrounding area. He is a founding member of Laika, a Romanian artists’ collective housed in a paintbrush factory in the ancient Transylvanian town of Cluj-Napoca. His paintings overlay the landscapes of Cluj and California: Romanian villages collide with orange sunsets and palm trees that Bercea possibly saw while driving in the Mojave Desert. In America (1988), Jean Baudrillard describes “driving as a spectacular form of amnesia. Everything is to be discovered, everything to be obliterated…”—a mystical conjecture that seems proved in the otherworldly forms, light, and colors of Bercea’s paintings.

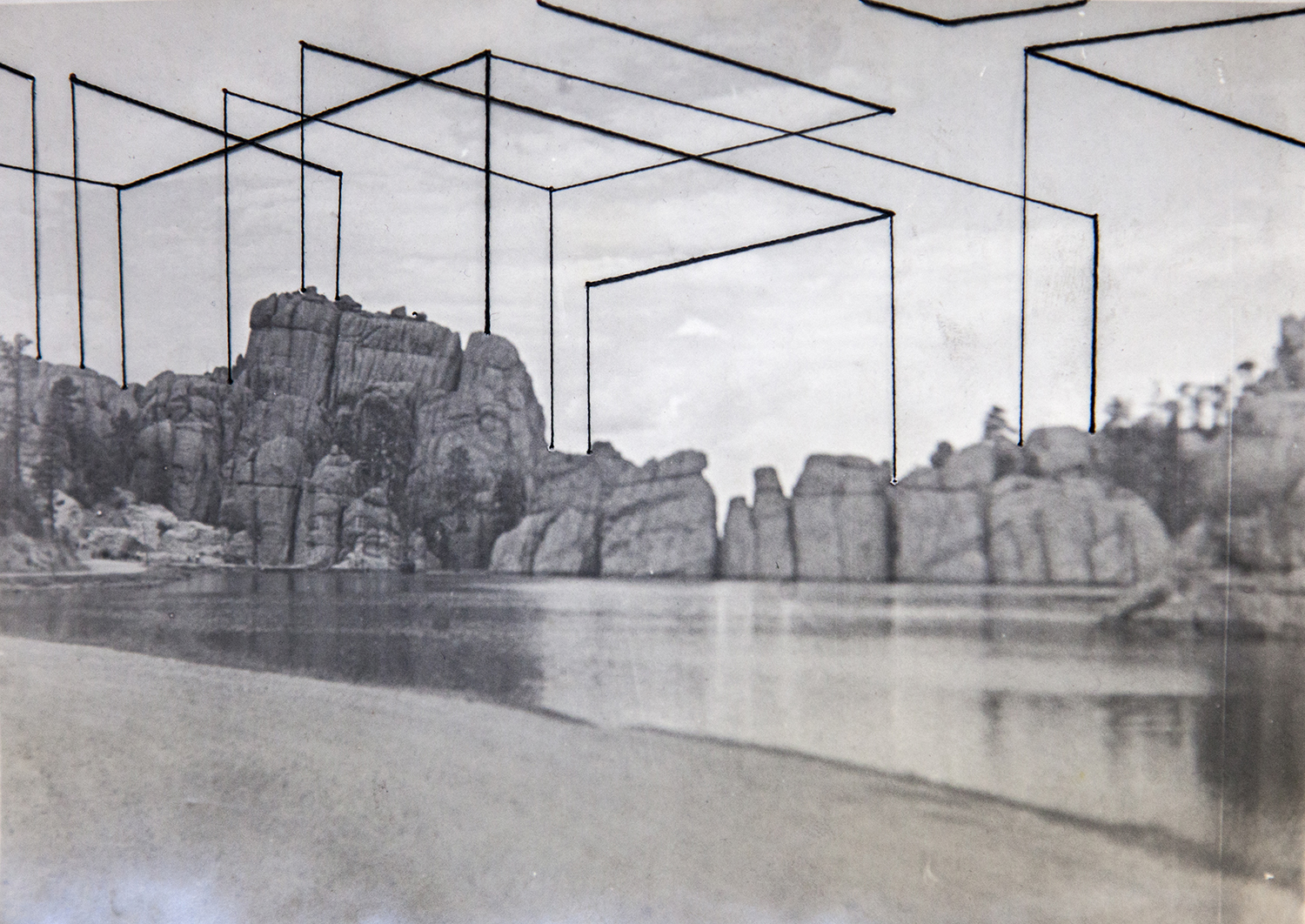

Maurizio Anzeri, On The Lake B3, 2015. Embroidery on found vintage photograph. Paper: 5 x 7 inches / Frame: 7 x 9 inches. Courtesy the artist and Haines Gallery

Maurizio Anzeri’s work usually features rich, fanciful embroidery sewn onto photographs collected from flea markets, with a surrealist and even sinister effect. At Haines, Anzeri’s 2015 series On The Lake features 16 images of vintage European photographs of Alpine Lakes onto which have been sewn elegant linear structures; the disquieting juxtapositions reveal what may be an invisible architecture of some future development or invisible models of magnetic energy fields.

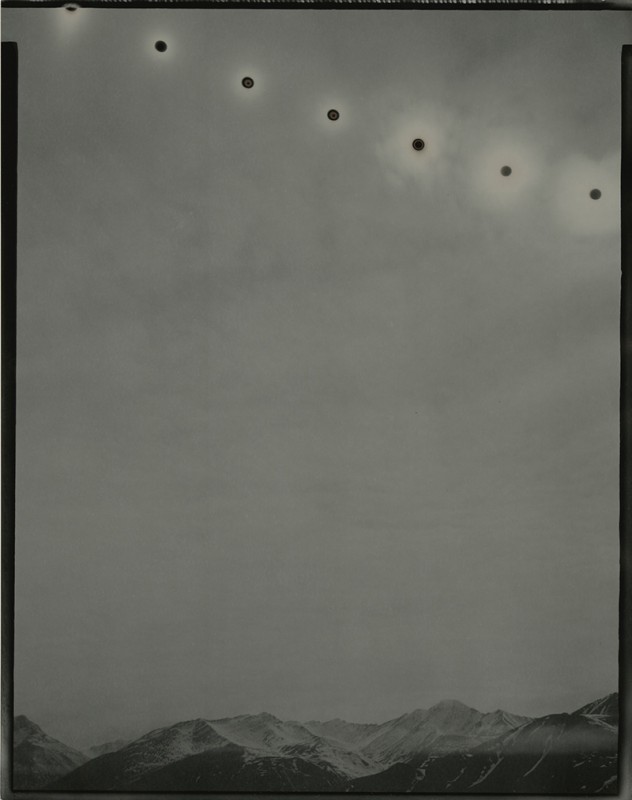

Chris McCaw, Sunburned GSP #814 (Alaska), 2014. Unique gelatin silver paper negative, Paper: 14 x 11 inches / Frame: 17.5 x 14.5 inches. Courtesy the artist and Haines Gallery

Chris McCaw’s Sunburn series of solarized photos were created with with large hand-built format cameras. Often with a portable darkroom on site and using pinhole camera technology with World War II military surveillance lenses, McCaw took long exposures on chemically treated paper or vintage 1960s and 1970s photo papers that allow the path of the sun literally to burn through and make a reverse image. His approach to photography is the result of an accident: a long exposure of the night sky followed by an unwanted sunrise that burned through his negative. The interaction of sun and vintage photographic papers creates a dreamlike magic in McCaw’s analogue photos through the recording of Earth’s daily cycles.

Linda Connor, Zephyr (Star), 2015. Sublimation on aluminum, Plate: 12 x 10 inches. Edition of 10. Courtesy the artist and Haines Gallery

Linda Connor is well known for her large format photographs of ancient sites in Nepal, India, Mexico, Peru, and Italy. Her process involves using special contact print papers. Her new series of photographic works uses “sublimation,” a process in which dyes are directly transferred onto aluminum (or other materials). Her photos depict details from Jacopo de’ Barbari’s extraordinary woodblock Bird’s Eye View of Venice (circa 1500), which features canals, streets, galleons among the waves—even zephyrs. The woodblocks themselves are hardly recognizable, but their textured, dark, almost burnt color reveals the ink-stained surface of the blocks (the reverse images of positive prints). This is very much in the spirit of Connor’s work, where the idea of time is deeply embedded in both the imagery and the way the print is made.

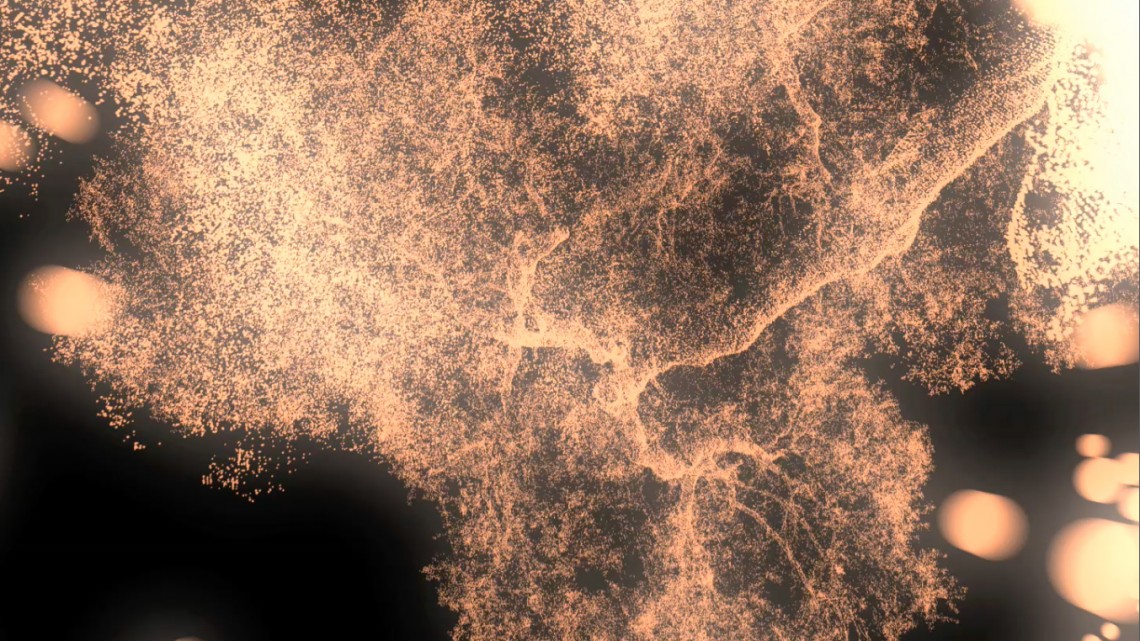

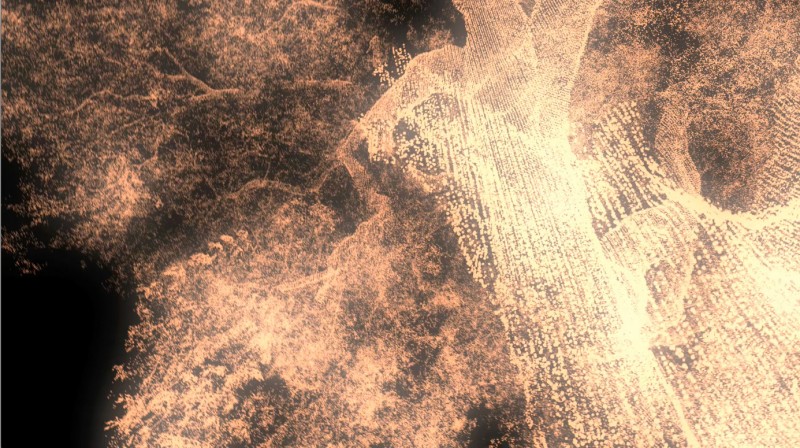

Pae White. Still from Dying Oak, 2009. Animation Film, 2:59 minute loop, 16:9

Dimensions Variable. Edition of 3. Courtesy of artist and Haines Gallery

For Dying Oak/Elephant, Pae White used imaging technology to map every surface of an 800-year-old dying oak tree in California. She turned this information into a point cloud, which, once animated, looked to White like an elephant and thus the title. The piece is a lyrical yet stately presentation of the tree—seen one moment from beneath its roots and looking up into its trunk, while in the next moment we are floating up at branch level and gazing into its crown, zooming in and out. White’s mesmerizing piece aligns itself with Herman Melville’s exhaustive descriptions of whales in Moby-Dick, so that once and for all we know exactly what will be lost once this particular oak tree dies. There is a beautiful, digitally-generated black-and-white single image of the oak on the outside of the projection room.

Installation view of The Mapmaker’s Dream, Haines Gallery. Courtesy of the artists and Haines Gallery

Curator and gallery director David Spalding wrote that White’s video was his starting point for The Mapmakers Dream. It evoked “a place where mapping—the communication of spatial information through graphic means—shades into something unexpected and fantastical. It was this set of intersections—between the cartographic and the wondrous, the scientific and the dreamlike . . .” that gave him the framework for the show. He asks us to consider that, “[i]n each of these cases, a map provides not an exact rendering of a place, or a set of territories to be annexed, but a set of imaginative coordinates, another possible worldview waiting to be considered.”[1]

Passing through this evocative show, I note the contours of this new territory: the elusiveness of metaphor, the visionary nature of art making, and the disappearance of dreams upon waking.

—

[1] David Spalding, e-mail message to author, November 16, 2015.