Richard Colman: Faces, Figures, Places, & Things

September 25 – November 6, 2015

Chandran Gallery

459 Geary, San Francisco CA 94109

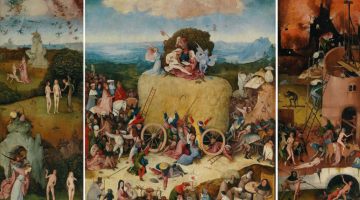

When taking in Colman’s new solo exhibition, Faces, Figures, Places, & Things at Chandran Gallery, the viewer seems to be peering into a hallucinogenic carnival mirror of sexual escapades. As recently as 2012, Colman was painting elaborate and fantastical stories set in landscapes that appear both futuristic and ancient. Featuring pyramids and theatrical stages, with people scattered about doing debaucherous things, the early works were elaborate narratives akin to Alejandro Jodorowsky’s film Holy Mountain or Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights. Colman grew up going to Catholic school and was surrounded by religious iconography, liturgical objects, and paintings. This influence can be seen in his work throughout the years, from the two-dimensional figures in illuminated manuscripts to candlesticks, evident in both early and the new work. Though the recent work is less graphic and almost innocent in comparison to earlier works, an endearing darkness lingers behind their provocatively decadent and lush facades.

Richard Colman. “Three Figures, Five Heads (orange),” 2015. Acrylic on canvas. Image courtesy of Richard Colman and Chandran Gallery.

Colman has shifted from earlier deep, earthen-tone grand narratives to brightly colored, intimate documentation of moments. The new work features tableaus of distorted nude bodies with repeated intertwining legs, and physically engaged couples, particularly women facing each other or men and women overlapping, cut into parts and reassembled as one fragmented form. Bodies dominate, and many severed heads appear. Three Figures, Five Heads (orange) (2015) in particular seems like a transitional piece away from the earlier works. The painting is a painstakingly rendered, minimal, ritualistic scene similar to an historical account on a fresco wall in Pompeii. Three nude figures in pale peach, pastel blue, and soft cream tones are bisected by a large soft pink leg bent into an unnatural square-ish angle. An outstretched hot pink arm holds a severed brown head; another blue head with pink hair is impaled on a pastel aqua arm, while the three bodies sit on three more heads. One inverted head, with its face turned away from the viewer to reveal its short cropped cobalt blue hair on a bright pink neck is particularly phallic. A lone figure exits the arrangement in the lower right hand corner of the frame—an accomplice that activates the space and is the only such reference in the exhibition.

Aside from the provocative subject matter, Colman’s tremendous use of color dominates the show. It is hard to achieve a balance when using so many different colors in one image, because there is a risk of creating unpleasant chaos and unwanted visual havoc that could detract from the images’ message. In his profile on the website Artsy, Colman claims, “I am not a natural colorist.” This seems hard to believe, but what he means is that it is very challenging for him to use color. Although, he could be considered one of the most adventurous colorists today. Neon pink and orange, and bright saturated cobalt blues and carnation pink tones are commonplace, but used in complementary and analogous ways next to other subdued olive, aqua or neutral greys and contrasting blacks. The white, black, and grey throughout the pieces calm the eye, allowing it to rest from the other vibrant and popping colors.

Richard Colman. “Orange Painting,” 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 36”x48”. Image courtesy of Richard Colman and Chandran Gallery

Colman successfully manages the balance between color and composition by flat geometric configurations, reminiscent of two-dimensional elongated legs and profiles found in Egyptian hieroglyphs or the geometry and flat perspective and multiple viewpoints on a single plane, as seen in cubism. In particular, Orange Painting (2015) features a crouching female in profile, painted in all orange against a vermilion background. In her right hand is a classical cream-colored vessel, above which she holds a severed head in her left hand, dripping red blood droplets that fall into the vessel. Her right leg, painted a shocking white, juts out at an impossible 45 degree angle from her bottom, and careens off to the side. This is perhaps the goriest of the work in the exhibition. Other works are less ritualistic and severe, using layered perspective and creating depth and softness with foliage. She Woman (2015) and In the Woods (2015) both include technicolor palm fronds and figures of women, which seem like a nod to Paul Gauguin’s paintings of Tahiti.

Richard Colman. “In The Woods,” 2015. Acrylic on Canvas, 192”x79”. Image courtesy of Richard Colman and Chandran Gallery.

The most striking and psychedelic are two pieces that emphasize the mirroring affect, creating kaleidoscopic patterns. In both Figures, Faces and Candles (2014) and Faces, Figures, Candles and Eyes (February 2015), multiple faces are aligned down the center, facing the viewer, looking upside down as the eye moves toward the bottom of the composition. Throughout, a dizzying array of stoic faces, beaming eyes and open mouths are surrounded by uncountable legs and arms, accented by candlesticks and lit candle flames: each shape its own color. Despite the Bacchanalian enterprise and all of the varied color, the symmetry of these pieces creates an effect of settling mystery rather than chaos.

Richard Colman. “Figures, Faces, Candles and Eyes (February 2015),” 2015. Acrylic on canvas, 36″x36″. Image courtesy of Richard Colman and Chandran Gallery

But, no piece conquers chaos more than the absolutely astonishing, monumental mural installed on the floor of the gallery’s lower level. Looking down upon it, the same symmetrical composition is larger than life—almost ten times larger. Heads are eight to ten feet in diameter, pupils are 24 inches or larger—legs are everywhere jutting out along the sides and disappearing into the walls. The piece in total is approximately 18 by 32 feet, glossy and ready to walk on. Colman has made floor works before, oftentimes using geometric abstraction as part of an installation. In an email exchange with Colman after the opening, he shared his thoughts on floor murals: “This is the largest, most involved painting I’ve made to date, so the fact that it was just going to be walked on—and quite possibly ruined in the process—I found interesting. Also for me, when I first entered the space and walked toward the back, I immediately looked down to the lower floor and my first thought was: ‘there should be a painting there.’”[1] The act of gazing down upon the piece sends a giant message about the way we look at art, and the way we view the subjects in it. Though Colman states that his intentions are not sexual, it is virtually impossible to desexualize nude, entangled bodies.

Richard Colman. “Untitled,” 2015. Floor installation comprised of several painted plywood panels laid on the floor. Image courtesy of Chandran Gallery.

Despite these elaborately provocative interpretations of the work, Colman maintains that his references are not sexual, but that the body is used as a mechanism for general, everyday human exchange. He wants us to believe that the scenes could reference any number of adult situations that arise on a daily basis—be it communication, solving problems, navigating work—allowing for the viewers’ own interpretation with the caveat that he is not intending a sexual read. With no clothing to hide behind, Colman’s figures are exposed in a vulnerable, unprotected state. Colman emphasized that clothing begins to identify the figure as someone specific, which is something that he wants to avoid. In reading the work, Colman sets up generic male and female bodies so that, “the viewer can feel free to imprint their own perspective on them,” while at the same time attempting to avoid gender specificity. “I am using the figure more as language I think, as words, sentences, paragraphs, so that obvious connections can be made to the work from various past cultures who used the figure in a similar way.”[2] However, this claim for ambiguity might be too broad when, clearly, the representation of intermingling bodies in Colman’s work is so charged with sexual tension.

Richard Colman. “Before and After Us (Two Figures),” 2015. Acrylic on Canvas, 80”x72”. Image courtesy of Richard

Colman.

Case in point, The Hair Eaters (2014) is an awkward yet erotically charged scene of two women whose long bright pink and red hair billows from their heads into the mouths of the other. Open, the lips receive the tresses, locking the two in what could be interpreted as a mutually trichophilic (hair fetishism) sexual exchange. Their grey and dark blue faces and French blue and creamy celery green toned bodies void of race, complement the salmon pink and bright aqua background. Before and After Us, (Two Figures) (2015), includes two women facing each other in an embrace. Their bodies hover over the cerulean blue, rich navy and midnight blue field. Their lips are parted, as if speaking to one another or about to kiss. Their legs are bent and folded in a jumble; the outstretched arms embrace their partners’ torsos below pairs of alert, red and purple, pointed nipples. For Colman, the piece in particular stands for intimacy, not sexuality: “It’s the sort of psychological dance or chess game that we play when someone may be becoming a part of our lives or when someone we have had a connection with is leaving it.” And that our unsaid thoughts sometimes have more impact than what we do or say: “How much do I let them in. What do I tell them, what do I not tell them,” he says.[3]

Knowing this, perhaps the viewers can approach the work from a more personal and generic perspective as Colman hopes, inserting themselves into the work in order to begin to read it more fully. Is this something that people do often, or are they always voyeurs gazing at others? It’s a complex question that completely changes how figurative art is perceived throughout history as objects for another’s gaze. In our post-modern, urban view, it is difficult to overlook the overall sexuality in Colman’s exhibition; the transparency of the actions and rawness of the nudity, painted with care and consideration parades sexuality. In fact, it seems all the more obvious that sexual tension pervades our culture and will perpetually cloud our gaze as long as we consider bodies as objects and perhaps even subjects of art.

—

[1] Richard Colman, e-mail exchange with author, September 27, 2015.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.