Matthew Barney: River of Fundament

September 13, 2015 – January 18, 2016

Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles

250 South Grand Avenue, Los Angeles, CA 90012

Much has been made of the meaninglessness and conjoining over-extravagance of Matthew Barney’s newest film and sculpture exhibition, River of Fundament, now on view at MOCA in Los Angeles, the only U.S. iteration of the traveling exhibition. Where his acclaimed video opus, The Cremaster Cycle, was released in stages over the course of several years and included differing locales and odd turns on in-depth, abstruse plot twists, River of Fundament is presented all in one gluttonous gulp of a sitting: a six-hour film with two brief intermissions. Not only does the film’s duration alone make it overwhelming to digest, but furthermore, the term digest has perhaps rarely been so apropos, as the film’s endpoint of fecal matter is at the crux not only of its conceptual framework but more viscerally, its visual referents. With all this buzz of the film’s unnecessary grotesquery, it is easy to approach the first of many hours of sitting in the black box at MOCA with a somewhat indifferent attitude, expecting shock value to rule and actual meaning to stagger meekly behind, trying to catch up. This is not entirely untrue, but regardless, it is nonetheless refreshing to see captivating imagery toppled upon itself so densely, even if much of one’s eye-widening is only due to the subject matter’s obvious depravity and spectacle therein.

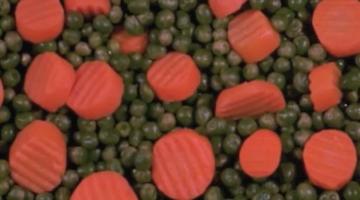

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler. “River of Fundament,” 2014. Production still, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, © Matthew Barney, photo by Chris Winget.

Within the first minutes of the film, Barney’s character emerges from the shit-filled “river” (which looks much more like just a dank, still, underground puddle of clay-water, which it in fact was), grabs a log of poo out of a toilet with his bare hands and covers it in gold leaf, and then proceeds to turn away from an older, equally filthy man whose penis and the gold-covered turd suddenly appear to be one and the same, in order to let him penetrate him. On the one hand it is annoying that anal sex between two men should be considered such a shocker within contemporary video art, but, on the other hand, it is still certainly more scintillating to look at, much less intellectually or emotionally consider, than, let’s say, a putty-colored abstract painting, the type of which still dominates many a vast white cube. This is not to dispel the ‘trumors’ that Barney’s signature tropes of grandiosity persist throughout Fundament, because they are undeniably there and they are often just as infuriating in their pseudo-intellectual tone as ever. However, as one has always been able to find buried deep within Barney’s amass of seemingly non-sequitur symbols and unusually manifested characters, there are clearly important nods and dissections of moments in history and literature that at times come to the film’s fuzzy fore. Not only that, but Fundament feels far less like a sculpture in video form, as Barney has in the past described his work on screen, and much more like a proper cinematic endeavor, with dialog (of sorts), formal readings and less formal liftings of seminal texts by renowned American authors including Hemingway, Burroughs and Whitman, and cameo performances by major actors, musicians and other artists including Paul Giamatti, Maggie Gyllenhaal, the late Elaine Stritch, Fran Lebowitz, Debbie Harry and Lawrence Weiner, to name just a few.

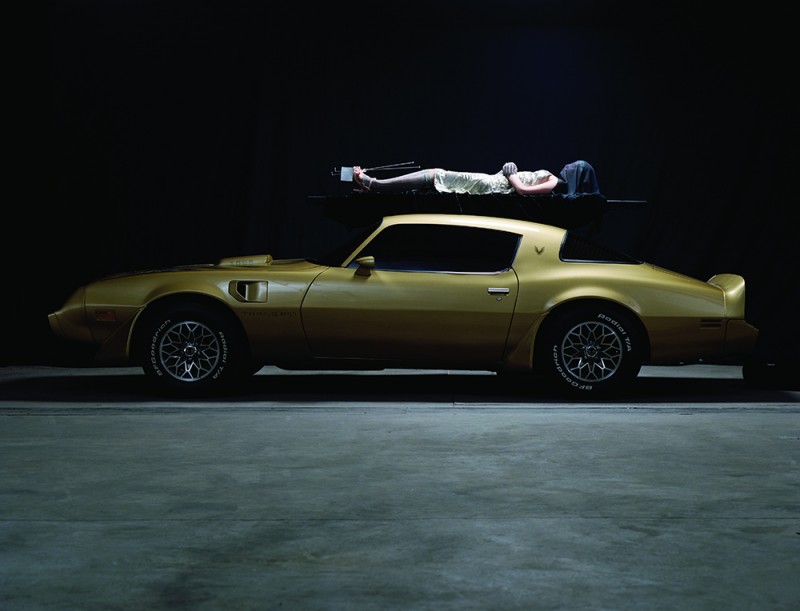

Matthew Barney and Jonathan Bepler. “River of Fundament,” 2014. Production still, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, © Matthew Barney, photo by Hugo Glendinning.

Most crucial to the entire movie is of course one of literature’s most celebrated, mysterious and self-aggrandizing figures, Norman Mailer, whom Barney cast as Harry Houdini (whose historical resonance has continued to arise throughout Barney’s work and again in later segments of Fundament), in Cremaster 2, which is loosely based on Mailer’s 1979 novel, The Executioner’s Song. The two had since continued an interesting friendship and discussed a potential collaboration that began when Mailer suggested that Barney read Ancient Evenings, a proposition he at first declined. The dialog connecting both of their symbolically shrouded practices was however cut short due to the infamous author’s death in 2007. In Fundament, Mailer’s belated absence leads to several other characters taking on various roles that represent him and his enduring spirit, including his son, John Buffalo Mailer, jazz percussionist, Milford Graves, and a hammered-down carcass of a 1967 Chrysler Imperial, which somehow magically inseminates a woman who later gives birth to a bird (one cannot help but see the through-line here as Barney continues to abstractly parse the demise of the American auto industry, which is also a strong theme throughout The Cremaster Cycle). The invisible character in the movie that runs throughout its strange and often disgusting permutations is Mailer’s highly criticized 1983 novel, Ancient Evenings. Though most of the interactions between the actors take place within a fabricated replica of Mailer’s oft-photographed Brooklyn Heights home in which they congregate to commemorate the writer’s colorful yet secretive life and career, the overall form that the film takes is one that mimics, congratulates, and reconfigures the misunderstood chronicles of Ancient Evenings, which is centered on various Egyptian myths of iconic gods such as Osiris and Isis, and processes of reincarnation, not the least of which is a scatological understanding of waste turned fertilizer.

Matthew Barney. “Canopic Chest,” 2009–11. Cast bronze, 73 1/2 × 165 × 243 in., installation view of Matthew Barney: RIVER OF FUNDAMENT at Haus der Kunst, 2014, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, photo by Maximilian Geuter.

As for the exhibition outside the black box, perhaps in relation to the film, it makes sense on some level, but the large, obtrusive works fall rather flat. While best known for his plastic, silicone and other synthetic, cream-like, oozing forms, the sculpture at MOCA, cast in rather uncommon materials for Barney, such as iron, bronze, sulfur, salt, zinc, lead, copper and of all things—wood, which he has in the past proclaimed never to work with, feel rather dormant and dull. Even visiting them during intermission and knowing that these are the very objects upon which certain characters pissed, causing the hallowing of the top surfaces of some of the large cube-shaped works, they somehow lack a tangible sense of activation. The lighting in the galleries seems far too stark, bright and frankly clinical to be presenting objects that audiences are all too well aware have been utilized in the telling of a story about death, decay, human excrement, rotting animals, anal sex, and machine on machine demolition. They don’t add to any desperately needed understanding of the overall meaning of the film, though they are large and commanding to look at from a distance.

Installation view of Matthew Barney: RIVER OF FUNDAMENT at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA, September 13, 2015–January 18, 2016, courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, photo by Fredrik Nilsen

With this massive undertaking, Barney has proven if nothing else, that he has his own identifiable way of making sense of history, even if that sense is made by merely putrefying and reconstructing various elements that seem not to fit together at the onset. He has created a film that could continue to be analyzed for years to come, and while that does not, in and of itself, make for a good work of art, it is difficult not to see its complexity as a valiant effort at producing and promoting work that does much more than please the eye (or in fact quite to the contrary in this case). River of Fundament may not be his finest work, but it is important to celebrate the fact that it is work of a certain caliber and at the same time incorporates historical, literary, musical, sexual and religious references, builds off of a set of interlocking narratives, uses sculptural sensibilities to create elaborate sets, costumes and make-up, and in the end demands not only the longstanding attention of its viewer, but moreover their will to make a concerted effort to connect its many confounding, distorted, and encoded dots.