Lee Kit: Please Wait

September 22 – October 31, 2015

mother’s tankstation

41-43 Watling Street, Ushers Island Dublin 8 Ireland

You expect big, big things when a thirty-something artist already has a Wikipedia page dedicated to him, right? I did. (Yes, anyone can create a page, but there is usually a reasonable breadth of information that accompanies an artist’s name in such a public arena.) Lee Kit has some heavy-hitting institutions attached to his name; he’s participated in group exhibitions at the New Museum, Tate Modern, and the most recent Venice Biennale (with a group of artists representing Hong Kong). His work has been shown at venues in Sydney, Hong Kong, New York London, Singapore, and Beijing. So, upon entering his solo exhibition Please Wait at mother’s tankstation in Dublin, I was ready for earth-shattering material. I didn’t get what I anticipated.

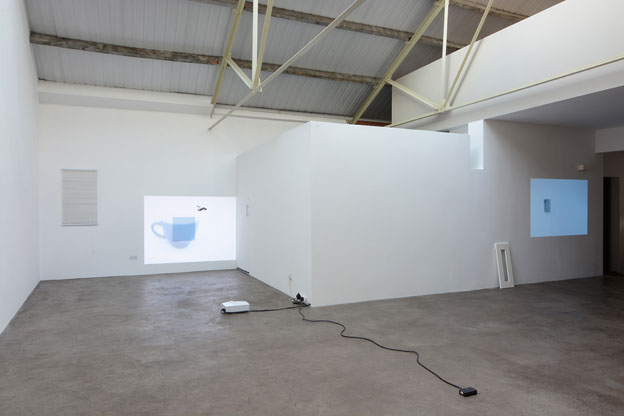

Lee Kit. “Please wait” Installation view. 2015. Courtesy mother’s tankstation.

Kit’s work is the epitome of reductive art: the least amount of physical matter meant to communicate a (desired) maximum amount of information. Isa Genzken began this recent trend with an absurd presentation of what was, essentially, refuse at the 2007 Venice Biennale. More recently, artists who have shown with programs such as The Approach (London) Lisa Cooley (New York), David Kordansky (Los Angeles), and practically every one of the galleries showing annually at Swiss fair Liste, have felt that appealing to any kind of tangible, figurative material would betray their “seriousness” about considering Modernity and its crisis of excess. Possibly the most over-celebrated and continuous practitioners of this “skinny supermodel” ethos of work is David Ostrowski: an artist who is claimed by one of his galleries to produce “a total analysis of the very nature of painting.” In fact, his canvases provide no advances or detectable changes in painting as a skill, but rather a degeneration of skill, altogether. This is not to say that painting or contemporary media should revert towards the Grand Salon-historical-scene or Greek nude aesthetic, but the opposite extreme doesn’t seem to hold the same mass appeal or interest. In any case, back to the problem with Kit.

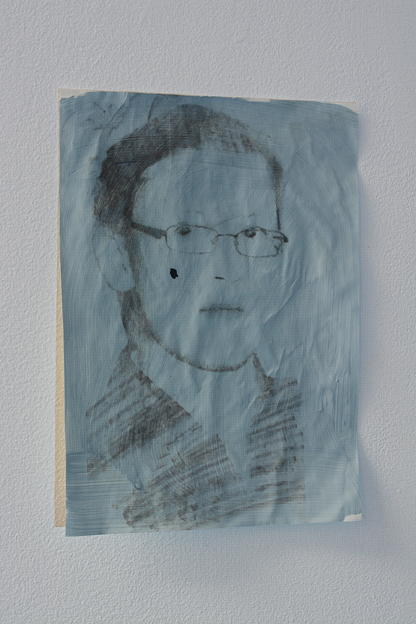

Lee Kit. “Portrait of a boy (detail),” 2015. Emulsion paint, pencil and inkjet on drawing paper, readymade objects, 2 plastic boxes, looped projection. Dimension variable. Projection size: 151 x 100cm, 16:9. Drawing size: 17.3 x 23.3 cm. Courtesy mother’s tankstation.

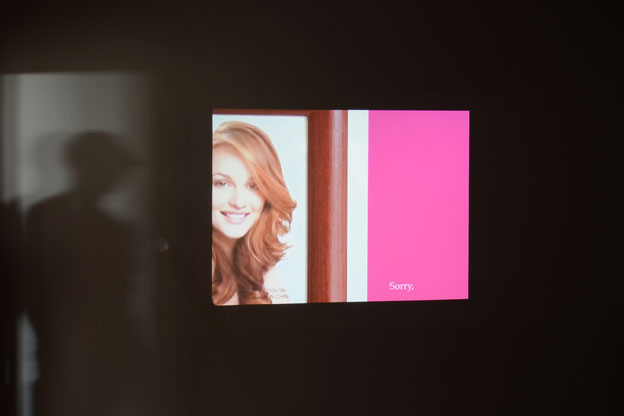

Small, delicate inkjet emulsions on baby blue-hued cardboard or paper depict hand signals, teacups, and a portrait of a young man. These are set alongside readymades (a row of hooks or a blue towel draped over an opening in the loft above), or within the luminous borders of a projection. But back in the first, darkened room, an exception appears: a looped digital video titled Sorry Betty (2015), which shows part of a picture with a female model’s face in a wooden frame (the kind of picture frame prepared for a typical department store). The model’s face is at times partially, sometimes halfway obscured by a solid pink color field. At the bottom edge of the pink sector, a series of subtitles reads, “Sorry, Betty. Sorry, Betty. I don’t know why I keep apologising,” and other bits of sheepish resignation. Perhaps it’s the intensity of the pink, perhaps it’s the obvious imprint “Made in China” in the bottom corner of the picture frame, but this work stands out for other reasons, as well.

Lee Kit. “Sorry Betty,” 2015. Digital video, looped. Projection size: 97 x 129cm, 4:3. Courtesy mother’s tankstation.

Kit’s combination of readymade objects and inkjet prints in the open gallery space feels spare, with little or nothing to grasp onto in terms of triggering memory, experience, or any kind of autobiographical narrative. Even the gallery text on the exhibition is of little help. The only other patron (an elderly man) said it best, as he handed the works list to me and sighed, “It won’t be much use to you.” Yet, Sorry Betty did possess echoes of John Baldessari, Martin Creed, and Sophie Calle in its attempt to access a hidden psychology in a seemingly lifeless product. The picture frame itself somehow had a voice and had a story to tell (although the larger context is purposefully concealed), and was struggling to tell it through a series of short phrases. There was consistent shifting and readjusting of the picture frame in the field of view, as if a hidden purchaser was trying to determine the frame’s best placement on a table, nightstand, or desk. You could be invested in this odd narrative, curious to see if and when a resolution might appear; this being a contemporary video work, you aren’t surprised when the video loops again with the same text, with no conclusion to offer.

Lee Kit. “A picture,” 2015. Emulsion paint, inkjet ink, pencil and correction fluid on lining paper, readymade objects. Dimensions variable. Painting size: 44.3 x 56cm. Courtesy of mother’s tankstation.

A blue towel, a bathmat or set of hooks, on their own, may act as agents of visual art as representations of larger issues, but set against Kit’s handiwork, they fail to produce a substantial dialogue. I could find no contextual clues as to what Kit was aiming to present to his viewers, and gravitating towards his drawings (in the hopes of gleaning some insight into his larger practice) was rather useless. Sorry Betty, however, delivered something in the way of visual and conceptual impact: it didn’t need to possess bright colors, or even a pretty model, to make its point regarding the haziness of word-image associations and the often selfish subtexts that create the standardized apology. Whether or not these observations point to the artist’s larger set of interests is still a mystery, but if this kind of exhibition is typical of what is reflected on such a robust CV, it leaves a lot to be desired.

Lee Kit. “Please wait”

Installation view. 2015. Courtesy mother’s tankstation.