Yoko Ono: One Woman Show (1960-1971)

May 17-Spetember 7, 2015

The Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019

Yoko Ono: One Woman Show (1960-1971) is an opportunity for the Museum of Modern Art to play off of a cute anecdote from 1971, when the artist staged a work titled Museum of Modern (F)art, an unauthorized conceptual piece placed outside of the museum.

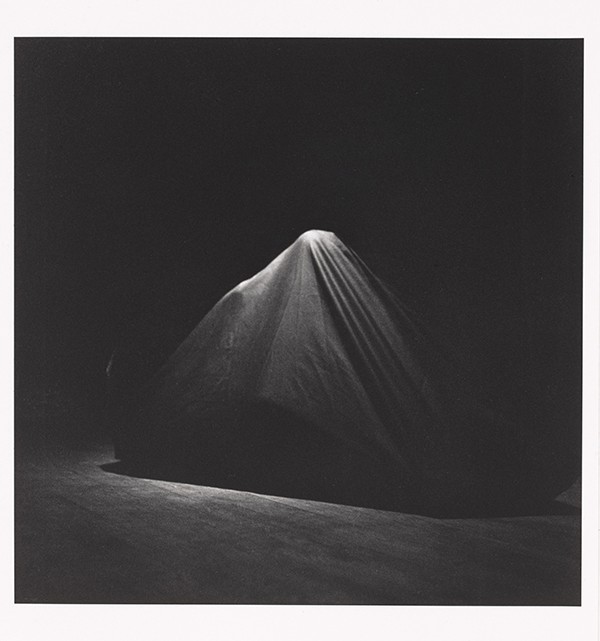

![Yoko Ono (Japanese, born 1933). "Museum of Modern [F]art," 1971. Exhibition catalogue, offset, 11 13/16 x 11 13/16 x 3/8″ (30 x 30 x 1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York. © Yoko Ono 2014](https://www.sfaq.us/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/14_yokoono_momfart_1971-790x800.jpg)

Yoko Ono (Japanese, born 1933). “Museum of Modern [F]art,” 1971. Exhibition catalogue, offset, 11 13/16 x 11 13/16 x 3/8″ (30 x 30 x 1 cm). The Museum of Modern Art Library, New York. © Yoko Ono 2014

Yoko Ono (Japanese, born 1933). “Apple,” 1966. Plexiglas pedestal, brass plaque, apple, 45 × 6 11/16 × 6 15/16″ (114.3 × 17 × 17.6 cm). Private collection. © Yoko Ono 2014

The first piece presented in the exhibition is Apple (1966), which is comprised of a single apple placed on top of a Plexiglas pedestal, including a plaque that says “Apple.” As the apple disintegrates with time it must be replaced by the museum staff—reminiscent of the value of transience, present within the wabi-sabi tradition. There were a few more Plexiglas containers, such as for Three Spoons (1967), inside of which were placed four “western-style” shiny silver spoons.

Yoko Ono interacting with people activating Bag Piece (1964), a participatory work in “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971,” on view at MoMA, May 17 -September 7, 2015. Photo by Ryan Muir © Yoko Ono

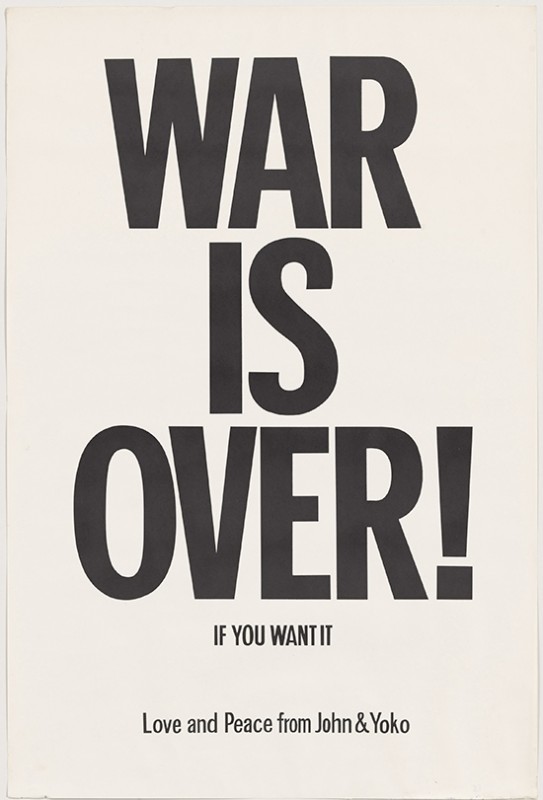

Although nuanced with poetic placements of objects and an homage to her Japanese roots, Ono’s main concern seems to be the framing of an exhibition (the pedestal, the title, the museum plaque.) One can’t help but notice, again, a potential interest in institutional critique and think of artists such as Marcel Broodthaers and Marcel Duchamp. But as Ono seems also to mock these framing devices, she nonetheless uses them as tools to document actions and to crystallize them into objects. The framing of Yoko Ono as an artist also holds a big role, almost too big as it seems to be justifying the very exhibition. In addition to being organized by chronological exhibitions and happenings, posters such as WAR IS OVER! if you want it (1969)—made with John Lennon—and exhibition posters are scattered throughout the exhibition.

Yoko Ono and John Lennon. “WAR IS OVER! if you want it,” 1969. Offset, 29 15/16 x 20” (76 x 50.8 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, 2008. © Yoko Ono 2014

When speaking of Japanese music, Jun’ichirō Tanizaki, the author of the famous 1933 book on Japanese aesthetics, In Praise of Shadows, calls it “a music of reticence, of atmosphere,” its most important attribute being “all the pauses.” This brings to mind John Cage’s 1953 piece titled 4’33”: a duration of 4 minutes and 33 seconds during which the performer does absolutely nothing, allowing the audience to absorb the sounds around them. Cage attributes his own exploration of silence to the discovery of Robert Rauschenberg’s White Painting [three panel] (1951), which he claimed were mirrors of the air: receptacles for the world and everything within it. In the 1960s, Ono created Sky Machine (1961-66), a stainless steel dispenser, which releases hand written cards by the artist bearing the word “sky,” intended to be placed on the streets of New York. For the current MoMA exhibition, Ono created a spiral staircase, To See the Sky (2015), which leads to a skylight, in an attempt to show viewers something they’ve never seen before.

There is no doubt that Yoko Ono, as a human being, critiques capitalism, the Vietnam war (by celebrating spiritual repose), and maybe even the museum institution, however, is it unclear whether her work does. This indecisiveness obscures the content of the artworks and only sheds light on its author who, by spreading herself very thin, showcases watered-down ideas from the political climate of the 60s and 70s.

Installation view of “Yoko Ono: One Woman Show, 1960-1971,” The Museum of Modern Art, New York, May 17–September 7, 2015. © 2015 The Museum of Modern Art. Photo: Thomas Griesel.